Craig G. Buck

Oral Histories of U.S. Diplomacy in Afghanistan, 2001–2021

Interviewed by: Bill Hammink

Initial interview date: December 7, 2022

Copyright 2022 ADST

Q: My name is Bill Hammink and I’m here to interview Craig Buck, a former USAID [United States Agency for International Development] mission director in Afghanistan and many other countries as part of the Oral Histories of U.S. Diplomacy in Afghanistan, an ADST project.

So, Craig, thank you very much for joining us today. So, if we can start, tell me if you can when you joined USAID and your experience and your career prior to going to Afghanistan, and what led you to go to Afghanistan as USAID mission director.

BUCK: My ending up in Afghanistan was like coming full circle, Bill. But, first, I want to thank you for your leadership in Afghanistan as well as for organizing these interviews and trying to ensure that we focus on something that is useful for the readers.

I joined AID as an intern in the spring of 1969, and when I first got a call welcoming me, I was advised that my first overseas assignment would be to Afghanistan. I responded with, “That sounds great, but you know, I’m a bit hesitant about Afghanistan” They came back about a week later saying, “Well, we’ve decided that you’re going to go to India instead of Afghanistan: And I said, “Well, that’s a bit of a disappointment.” And a week later, they called and said, “We’ve changed it again, and you’re going to go to Turkey.” At that point, I said, “Perhaps you misread my resumé. I just finished graduate work in Latin America studies.” (laughs) And they said that’s how Personnel works. So, I ended up going to Turkey, but the circle was completed when I ended up in Afghanistan on my last posting in 2002.

I went to Turkey and spent three years there as a junior officer in the Program Office, getting the normal rotations that one goes through to become immersed in AID, its practices, protocols, and culture. One of the best things that happened while I was there was that a new AID director [who had just come out after being the Agency’s director of Personnel] took me under his wing, became my mentor, and invited me to participate in the twice weekly senior staff meeting. I became the one the notetaker, digested the most significant issues, analysis, and conclusions, and sent them back to the desk. That was a great opportunity to see how senior management dealt with issues, what their concerns were, how they handled them, how USAID worked with other country team members and the ambassador, and how the field interacted with AID Washington. I also became a special assistant to the director and covered a variety of issues that no one else in the mission was handling

After Turkey, I went back to Washington for several assignments that gave me good insight into the interagency process, relations with the Hill, and working with State. I was a program analyst for a short while with the Latin American Bureau, the desk officer for Turkey as USAID ended its assistance program there, and detailed to the State Department on international narcotics matters as drugs became a key element in U.S. foreign policy. After a stint on the Egypt Desk in 1979 I went off on long-term training at AID’s expense; this was one of the best things that happened to me in AID. I returned to Stanford University, but this time in the field of economics at the Food Research Institute, an interdisciplinary program comprised mostly of economists. While I had envisaged the year as an opportunity to take electives to “broaden my horizons,” the university thought differently and intended that I get another degree. They forced me to really study hard, and I learned quite a bit about international development, the major institutional players, finance, business, and economics. I had a minor in economics as an undergraduate, but the year at Stanford really helped me appreciate the centrality of economics within the social sciences and international development. More importantly, it gave me a new maturity and appreciation of development issues that would serve me as I moved into more senior positions.

After Stanford, I went to Uganda and reopened the USAID program there, which had been closed for seven years during Idi Amin’s tenure. I ended up as the acting AID director. After three years in Uganda I went to the Dominican Republic and later had another short tour in Washington. In 1989 I went to Peru as the AID director. Besides Turkey, Peru was the only USAID mission I ever served in that had an existing, ongoing program when I arrived. In Peru, I worked in an environment of civil strife, terrorist threats, political chaos, ethnic conflict, and narcotics production and trafficking. With the fall of the Berlin wall and breakup of the former Soviet Union, I got a call in mid-1993 saying that they wanted me to set up a regional AID mission in Central Asia. I left Peru immediately and directed the establishment of AID missions in the five newly independent Central Asian countries: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan. This was a totally new experience in an area of the world that I had virtually no knowledge of and establishing programs in a totally new context. It was quite challenging and with the five countries, I had to spend about half my time on the road coordinating activities with the five new ambassadors, getting programs underway, and establishing offices.

After three years in the former Soviet Union, I got a phone call one night from the AID administrator [Brian Atwood], saying that it looked like the war in the former Yugoslavia might be drawing to an end. In anticipation of the conflict the administrator asked me to go there for a couple of weeks to see what contribution AID might make to cementing a peace settlement. I took off immediately and spent about three weeks in Bosnia and Herzegovina looking into development problems and opportunities. I went back to Washington and met with Atwood and his senior staff and gave them my analysis of the more significant post-war problems, challenges, opportunities, and recommendations on priorities that AID might want to concentrate on. At the end of a long session, Atwood said something along the lines of, “That sounds like a pretty good way to approach the most immediate problems, so I want you to go out there and get the program started.” I replied, “That’s not exactly what I signed up for. I thought I was going to the Balkans only for a short assessment.” Anyhow, I got on the plane back for Sarajevo, and while I was en route, the Dayton Peace Accords were signed. There was enormous interest in helping reconstruct Bosnia within USAID and the international community, and we were able to get the personnel and resources quickly to get a massive post-conflict rehabilitation program underway.

While in Bosnia, we closely followed the inter-ethnic and political problems in Kosovo, the expulsion of Kosovars from their homes and the province, and the later NATO [North Atlantic Treaty Organization] military intervention to end the conflict. In the midst of kinetic activities, I got a call asking me to take on Kosovo and so using some of the resources that we had in Bosnia, I moved down to Kosovo and got the reconstruction program started there. I managed both the Bosnia and Kosovo programs together for over a year. As the Kosovo program moved forward, U.S. policy supported the increasingly autonomous efforts of Montenegro to reduce ties to Serbia. We opened up an AID mission in Montenegro and initiated a significant economic program that supported Montenegro’s financial independence from Belgrade, along with a modest democratic development program promoting increased local autonomy and private civic organizations.

On September 11, 2001, I was in Sofia, Bulgaria at an AID ANE Bureau [Asia and the Near East Bureau] mission directors’ conference, along with the AID administrator, Andrew Natsios. We, of course, were very concerned about what was happening and began to think about what the consequences of the terrorist attack might be, and I kind of saw the handwriting on the wall. I figured that if the U.S. were to go into Afghanistan and a non-Taliban government were in power, then an AID mission would quickly follow, and it did. I got a late phone call again at the end of 2001 and set off for Afghanistan as soon as we could accommodate new management in Kosovo. So, as I said at the beginning, I’d come full circle and finally ended up in Afghanistan; after being told that would be my first assignment with AID, it turned out to be my last.

If I can, I’d like to get into what I saw when I got there and how we got the program underway.

Q: Absolutely, yes, thank you.

BUCK: The exciting thing about setting up new AID programs, and especially in a place like Afghanistan, is that you have a tabula rasa. You have no major prior constraints on what you might do in terms of a program, you have no mortgage to deal with, you have no stockholders that you have to take care of. Special interests are there, but they’re not really at that moment the most important thing in your life. There are no contractors or lobbies vociferously pushing their cause, and the Embassy and normal Washington foreign policy pressures on AID are preoccupied with the conflict and political issues such that the dimensions and structure of a reconstruction program are an afterthought to be worried about later. There are normal AID earmarks, but nothing yet concrete about the country that you’re working in. One must keep in mind that at some later point, all the usual interests and pressures that influence foreign policy will come to bear, but at the initial stage one is not tethered to them in conceptualizing a new program. So, you have the opportunity to think about the country’s key constraints and development issues and what would be the best way to address them.

I got very little guidance from AID in Washington on what the AID program should focus on and try to accomplish. AID Administrator Natsios asked that we give attention to the humanitarian issues related to the civil conflict and to returning refugees and displaced people. He also suggested that we pay close attention to a recent analysis done by an EU [European Union]-sponsored expert recommending a comprehensive rural development approach to Afghanistan’s problems. Beyond advising that we should prepare for a massive, yet unfunded, reconstruction program, I had no instructions on the composition, length, or goals for the assistance program. More importantly, at no point did I get a sense from key interlocutors in State, NSC [National Security Council], Defense Department, Treasure, and other government agencies about how they viewed the economic assistance fitting into achieving key foreign policy objectives in Afghanistan and how AID could be used to advance our interests. Most advice I got from around the table in Washington was canned and often conflicting platitudes such as, “Show the flag; make something happen; make a quick impact, work with the military; help the poor; work with other donors, get out front on reconstruction, build the central government, support local authorities,” et cetera.

Compounding the problem of determining what the AID program should focus on was the dearth of information on the social and economic status of the country. None of the usual country statistical, institutional, and policy information by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund had yet been published. There were few foreign or local experts at that point with knowledge of Afghanistan’s comprehensive needs. Other donors already were expressing interest but in the beginning none were able to discuss priorities or make commitments to provide leadership in any discrete area beyond the European study I just mentioned. There was hardly anyone that I could talk with and get some recommendations from, someone that had experience in the area that might have suggestions on what we should do. Few private sector representatives were available and only a few local civic organizations existed that we could consult on program directions. Most public officials were representatives of certain regions or interests, were tied to regional warlords, or were such recent returnees that they were not qualified to speak authoritatively of country-wide development issues. Of course, there were constant pleas from all sides for assistance, but given the country’s enormous needs at that point, it was not possible to prioritize the most urgent. In countless meetings, Dr. Ashraf Ghani, the then head of the Interim Afghan Assistance Coordination Unit [AACU], eloquently described the country’s myriad problems and needs. But, he counseled that AID should define its own portfolio and then he would determine if they fit within the AACU’s priorities or needed to be modified to better serve Afghanistan. With fighting still going on around the country, the ambassador was preoccupied with other issues but suggested we keep infrastructure repair in mind as President Karzai had mentioned rehabilitating the Ring Road as something the United States might take on.

AID itself had no overall framework for how you set up a new USAID mission, what issues you should look at, what problems you should be concerned with, and how you should think about programming resources. Further, AID had no programmatic framework for handling the logistical, management, and personnel issues associated with setting up a new mission on an urgent basis. Because the mission was new, it fell outside the normal timeframe for programming resources, personnel assignments, and decision-making support structures and deadlines. Thus, any new program financing, operating expense, personnel, or management bandwidth initially would require a reprogramming of existing limited financial and management resources and the additional bureaucratic processes this would entail.

Over nine or ten years ago, USAID’s Jim Smith came up with a superb document providing guidance on programming resources for economic growth in post-conflict situations. That guidance [though published some years after the fact for my purposes] is superb and reflects basically what AID did in Bosnia, Kosovo, and Afghanistan. But there was no similar overall comprehensive guidance on what to consider and what sort of strategic direction AID should take in post-conflict countries or working in complex, ethnically based conflict situations. Further, there was no strategic guidance manual by AID for analyzing and programming resources in discrete economic and social sectors, for democratic development, or for cross-cutting issues such as the environment or promoting gender equality. This would include, for example, say, civil society, rule of law, private sector business enabling environment, or agriculture, all from a post-conflict perspective.

Afghanistan’s development needs were overwhelming. Severe poverty was endemic. Inflation was rampant, no local commercial banks functioned, there was no confidence in the Afghani currency and people stored value in external currencies, unemployment was sky-high, most public infrastructure had been damaged or deteriorated, and an enabling environment promoting growth did not exist. Security remained a major problem and public safety personnel were venal and stifled commercial confidence and activity. Thousands of former combatants needed to be demobilized and reintegrated into a non-kinetic environment. Millions of refugees and displaced people were returning to their homes, food security was problematic, especially among returnees, public health services hardly functioned, women were still virtually outside the labor force and girls were only beginning to return to school. Over the Taliban years, there was a virtual collapse of government institutions and resources to carry out public service programs; government skill levels were abysmal. Few local civic organizations existed and there was no legal framework to nourish them.

Despite the enormity of its problems, a number of factors gave us some confidence that the country could begin to address its problems. For many, there was a sense of euphoria in being out from under the suffocating control of the Taliban. The Afghan people were hardworking, practical, resilient, and eager to capitalize on the new freedom and security the post-Taliban period promised. Many people wanted to work with the United States and USAID so there was a good group of people who ultimately became our stakeholders. Women were again allowed to get an education or to work outside the home. Refugees brought new ideas and a more educated population back to the country. The returning diaspora brought many highly skilled entrepreneurs and managers that might contribute to private and public sector management and growth. Large numbers of external donors and private organizations were eager to work with the Afghans and to bring significant resources with them. As the Afghan government began to function, policies were largely pragmatic and market-oriented. It allowed press freedoms and initially supported the development of an independent, impartial, and professional judiciary. The interim government gave the appearance of wanting to consider all views without centralizing all decision-making in Kabul.

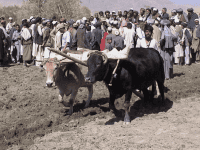

Our highest priority initially was helping address the urgent humanitarian crisis caused by the disruptions and displacements accompanying the routing of the Taliban. These problems were exacerbated by extreme drought over the previous three years and the almost complete dysfunction of the public health system. Compounding these strains on resources were the return of millions of Afghans who had previously sought asylum in Pakistan or Iran. Most looked to resettle in their former homes, which frequently were damaged, with farm implements, equipment, and livestock missing. The drought, disruptions, and returns and resulting food insecurity were major challenges. Several representatives from USAID’s Disaster Assistance Relief Team [DART] of the Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance [OFDA] arrived about the same time I did in the first quarter of 2002. While the UNHCR [UN High Commissioner for Refugees] was the primary organization assisting returnees, the DART team was critical to evaluating financial needs to justify the U.S. contribution to UNHCR. More importantly, they quickly set up programs for housing rehabilitation and managing food distribution. They also contributed to an initial health system rehabilitation activity that mobilized nongovernmental organizations to provide services the public ministry was unable to provide. The DART team provided critical analytical services to ascertain the dimensions of the food security problem and food distribution programs managed by the WFP [World Food Program]. Inasmuch as the United States provided some 75 percent of overall WFP resources, our analysis was important to justify funding levels and to ensure the most appropriate programs to get food into the mouths of the most needy. OFDA humanitarian relief activities were critical to helping the massive return of migrants and displaced people. One critical activity OFDA carried out was the emergency rehabilitation of the Salang tunnel, which opened a vital corridor to transit from Kabul to the northern provinces and to traffic from Uzbekistan and Central Asia. Programs providing essential household items [blankets, kitchen needs, hygiene products, et cetera] were important to helping returnees resettle in their homes. Assisting with transport, tents, and plastic sheeting were continuing needs that OFDA helped meet.

Besides the DART team, we also had an Office of Transition Initiatives [OTI] team on the ground from the beginning. Their work in various ministry offices, work with civil society, their knowledge of the local situation, their recruitment of personnel who ultimately moved into the USAID mission helped ground truth our understanding of local realities. OTI set up a series of small grants to nascent civil society organizations, to local independent media, and to support women in the workplace. The OTI team helped identify future leaders to work with, potential democratic development work that could be expanded and accelerated, and corrupt officials and practices we needed to avoid. The OTI program was vital to reestablishing certain vital government functions. In early 2002 most government offices were severely dilapidated, had been looted, suffered war damage, and lacked security. Most had no electrical or public utility connections, heating, or internet connection. The OTI program very rapidly provided the essential office space and public safety for a number of ministries and departments, enabling them to operate. Many activities opened opportunities for women in the workforce by reconstructing space for child care or pump rooms in government facilities. The same rapid reconstruction programs were initiated for schools, kindergartens, health clinics, markets, and community facilities. These rapid reconstruction, training, and skills transfer programs, numbering in the hundreds and completed within the first year after the defeat of the Taliban, brought great credit on the United States. Even though many other donors were contemplating assistance programs and sent teams to consider investments, the United States was practically the only donor with very visible, high-profile programs underway on the ground. OTI also had a logistical support and program implementation mechanism working through a contractor with the International Organization for Migration [IOM] that enabled it to function in the resource-poor environment and to mount small programs with qualified personnel very quickly.

After ensuring that the emergency humanitarian needs were being addressed, we focused on developing and putting in place a reconstruction and growth program. Getting employment and incomes up was critical. The most appropriate way to accomplish this, we thought, was to set up the institutions and enabling environment that would facilitate private sector employment, investment, and commerce. This would require working with key government ministries and banks, beginning with the Ministry of Finance. Dr. Ashraf Ghani, who had been the head of the Afghan Assistance Coordination Unit when I arrived, moved to the Ministry of Finance after the first Loya Jirga, and he became our chief interlocutor. Like most other government institutions, the Ministry of Finance had become moribund under the Taliban. It was not capable of mobilizing and collecting resources, budgeting and determining priority uses of funds, disbursing and accounting for expenditures, and ensuring the proper use of resources. With a largely illiterate and innumerate staff, there was little institutional strength to build on. So, we set about helping the Ministry of Finance establish and exercise the basic instruments of fiscal governance. Using expedited procurement procedures and by waiving many of AID’s usual bureaucratic processes, we had a contractor in place and in country within four months. The large team we brought in had some sixty-five expert advisors initially. Their mandate was to draft the organizational structure of the Ministry, define the functions of each section, and exercise Ministry functions or counsel incumbents until trained staff were on board. They were also responsible for establishing a training function to get personnel to the level that they could quickly replace expat advisors. Among other accomplishments, the team set up a basic treasury function, a taxation section to define revenue sources and operationalize collections, and a budgeting section to analyze priorities and operationalize funding decisions once guidance was given by the executive. The ministry also began to develop the capacity to examine key future decisions such as a pension system or health care finance and to forecast macroeconomic conditions and determine their impact on the budget as well as measuring fundamental economic phenomena over time.

The other element of economic governance was the monetary side. When I arrived in early 2002, the Central Bank was in virtual disarray and the rate of inflation rate was quite high although there was no formal measure. The Afghani currency was badly in need of reform with many Afghans relying on the Pakistani rupee or Iranian rial as their preferred currency. Fortunately, we had a good interlocutor with the first Governor of the Central Bank, Dr. Anwar al-Ahady, part of the highly skilled executive-level diaspora that had returned to Afghanistan in the heady days immediately after the fall of the Taliban. Our contract team worked with Dr. al-Ahady on the organic decree to establish a Central Bank as an independent institution. Previously the Central Bank was an appendage of the Finance Ministry, and performed the payments function for the government. Also, although the Central Bank nominally was responsible for foreign exchange management, almost all foreign currency transactions were carried out through the very effective informal “hawala” system. Defining the structure of the Central Bank got us involved in a local political issue as Dr. Ghani was loath to have an organization such as the Bank outside his purview. Heretofore the Finance Ministry had performed normal central banking functions. But, along with the IMF [International Monetary Fund] and others the Afghans acknowledged the importance of an independent institution. We worked on the organic law of the Central Bank and then subsequently on drafting the laws governing commercial banks, bank regulation and supervision, foreign currency exchange and management, Central Bank relations with the Treasury and a series of other instructions and regulations governing bank fiduciary responsibilities. All these management and regulatory authorities were designed to help make commercial banks responsible fiduciary institutions so that they could mobilize resources and promote growth and employment.

One of the most important things that we did early on was spearhead the currency conversion. By early 2001 the Afghan currency, the Afghani, had depreciated sharply against other currencies. The amount of currency one needed to carry out even the smallest transaction required having a wad of bills, greatly impeding commerce. We viewed the introduction of a new currency as a real priority as it would demonstrate government interest and concern with problems the common Afghan faced and the government’s capacity to act with alacrity. Other partners including the IMF warned that it would be too difficult to implement so early in the new government. Nevertheless, at the Central Bank’s urging we took the lead to get large amounts of the new currency out and distributed so it would be exchanged for the old currency at a rate of a thousand old Afghanis to one new Afghani. We worked with the Germans, who actually did the printing of the new currency. The military was very helpful in providing security and transport of the new currency to many areas because we had to safeguard new Afghanis while transporting it throughout the entire country. This was at a time when there were still security concerns to say nothing of our fiduciary interest in protecting the new Afghani. That is, you don’t want to leave the bank doors open. So, we had to ensure a secure means of having people come in with their old Afghanis and receive an equivalent amount in the new currency. Then we had to get the old bills back to Kabul in the same secure channels so they could be verified and destroyed. But that was something that we managed to do I thought quite well, and the whole process of getting the new currency out and getting everybody to turn in their old currency which was then destroyed was done within four to six weeks. This conversion process, I thought, was one of the real success stories early on. People had confidence in the new Afghani and it was a fundamental building block to economic growth. So, getting the framework for economic growth, the things that would facilitate the private sector, would facilitate investment, would facilitate confidence, that would get people seeing that the government had a framework to promote growth and investment was one of the most significant early things that we did.

The second area that was seen that could quickly produce growth and provide employment was through infrastructure rehabilitation. For almost a generation, there was little investment in the maintenance of the country’s infrastructure needed for commercial activity and to meet social and consumer needs. Roads had deteriorated, bridges had collapsed, electrical power generation and distribution had deteriorated, schools and health clinics were run down and unrepaired, and water and sewerage systems were dysfunctional. Along with the problems associated with the lack of investment and maintenance over the years was considerable damage from fighting over the past several decades as well as that related to the overthrow of the Taliban. Early on the Ambassador had indicated that President Karzai was interested in road reconstruction and asked that I investigate what we could do. Since we were in the process of putting together the project documentation for a large infrastructure rehabilitation program we did a quick survey of the requirements for rehabilitating the Ring Road. The Ring Road was the main highway making a circle around the country, starting in Kabul then southwest to Kandahar, then north to Herat, and back to Kabul. The road had been constructed in the 1950s and 60s primarily with U.S. assistance. The survey indicated that it would take around one billion dollars and more than three years to rehabilitate, assuming that security was not a significant problem.

As we were working on the infrastructure activity documentation and authorization, trying to get the paperwork done and get an implementing contractor on board, I was advised that the White House thought that the Ring Road was a priority and that we should be giving that real attention. We had concerns out in the field about it, to say nothing of the cost as well as the fact that sufficient reconstructing funding had not yet been authorized by Congress. While we could appreciate the political impact that rebuilding the Road might have, economists point out that farm-to-market and feeder roads have the greatest economic development impact for transport sector investments. On the other hand, we are not just developmentalists and we understand political realities. And so, when word came from Washington that the President had talked with Karzai and that he wanted a road, I called Dr. Ghani, and we agreed basically over the telephone that this was where we would put the major part of our infrastructure resources. In September, President Bush announced that the United States would be helping reconstruct the Ring Road.

The Ring Road was a major priority and an impediment to our focusing on more important reconstruction issues over the next several years. We did not have sufficient funding with just AID resources so we had to try to interest other donors in providing parallel or direct funding. The Japanese were most interested in working with us but wanted to reconstruct only the first forty kilometers beginning in Kabul. The Japanese Government had recently made a donation of a large amount of construction equipment to local authorities in Kandahar, and was concerned about the resources being used appropriately; thus, we urged them to take on the road beginning in Kandahar toward Kabul. After endless meetings and consultations with Tokyo they agreed but continued to complain that AID took the first and easiest section starting from Kabul. [The Japanese would never accept that the first twenty kilometers had already been repaved in 2001 and that by the time we had an agreement on construction, AID was already repaving the remainder of that section].

Even with the Japanese contribution, which came to around forty million dollars, we were still far short of the funding needed for the Road. In addition, the Road had a gap in the northwest [from Herat through Mazar-i Sharif and back to Kabul] that had never been part of the Ring and we needed to find sponsors for that section. We canvassed other donors in Kabul to work with us on the project. Ultimately we got the IBRD, the Saudis, the Islamic Development Bank and others to make modest contributions. I was disappointed in the lack of an aggressive approach to securing other donor funding from Washington offices. From my perspective, the field was left holding the bag to find money to fulfill a Washington commitment. Ambassador Bill Taylor, who was in Kabul for a while as an assistance coordinator pushed Washington to help secure funding, and as I recall, traveled to the Middle East passing the hat, but was not able to secure the full funding needed.

Executing the decision to move on the Ring Road was a major field management problem. First, we had to mobilize our prime contractor in record time and under great pressure to get its staff in the field, local subcontractors on board, and equipment in place. This kept us from urgently financing the reconstruction of other priority activities, such as schools and health clinics, that would have a much greater economic and political impact than the Road. The Afghan Ministry of Public Works was insistent that we provide funding directly to them so they could do the reconstruction, but that would have entailed significant accountability problems. Dr. Ghani asked that we give the money directly to the Finance Ministry and he would arrange for contractors to implement the work, but that had equally unacceptable accountability problems. Even our Japanese co-financers had problems initially with our approach of using a reputable prime contractor that was responsible for managing subs to do most of the actual “brick and mortar” work. The Japanese initially wanted to give funds and equipment the Japanese had procured directly to local authorities for them to execute. Compounding our field implementation problems [for which we had only one USAID officer who had other major responsibilities] were the incessant calls for status information and visitors from a plethora of offices in Washington––the White House, NSC, State, AID, the Hill, contractors, and NGOs––who all wanted to see construction underway immediately.

In spite of these problems, we were able to inaugurate the initiation of the project in late June 2003, when we began paving the first forty kilometers of new tarmac on the road from Kabul to Gardez. We were all very proud to get this project underway; it was an indication of how AID can really work when they want to do something quickly. We started talking about the project, and within six months, we had our program underway, and we were laying asphalt.

The infrastructure program not only enabled us to rehabilitate the Ring Road, but also was a vehicle for us to greatly expand activities already underway in education and health through two grants AID Washington had arranged. The education sector grant was critical to our efforts to help reintegrate women into society. It was a primary school textbook program that the University of Nebraska took the lead on. The University was responsible for printing approximately 1.5 million textbooks and for ensuring their distribution to all primary schools. Earlier estimates suggested that 1.5 million textbooks should be adequate to handle the number of students that would be starting school. The estimates were very rough as there was no information available from the government regarding school enrollment. As it turned out, the 1.5 million texts only covered about 50 percent of the students who went to school that year. While we were disappointed that we had greatly underestimated the number of students, we were pleased that so many people were showing interest in education, particularly girls, who were allowed back for the first time since the Taliban took over. We quickly turned to printing another round of books twice the size of the original distribution.

Like other aspects of our program, once implementation was in full swing unanticipated issues that impacted on the program began to surface. As I recall, I believe we printed between twenty-five to thirty sets of texts for each school; the content of each book mirrored that being used in the early 1980s. In the urgency of getting the textbooks printed and delivered our contractor quickly looked over the contents, made a few modifications, and moved to print in order to get books into the hands of students for the start of the school year. We simply didn’t have time to fiddle around with the content. But then several foreign groups criticized the program alleging we were printing religious propaganda. Apparently, there were three books that were the most contentious that had a few paragraphs on religious subjects. We quickly headed off the concerns by working with our colleagues in UNICEF [United Nations Children’s Fund] and other donors. We arranged for them to finance the printing of the objectionable books which we added to the much larger list of books we printed in the second round for school the next year.

While the provision of elementary school books was an initial element of our intervention in the education sector, refresher training for teachers and administrators was another key element of our program. Emphasis in the refresher courses was given to girls education and to encouraging girls to attend and continue in school. One of the interesting things that we did in education was that many girls that were going back to school after having dropped out six or seven years earlier. Many had gone to one or two years of primary school, and upon their return some years later, were sitting next to children that were quite a bit younger than they were. We developed a special program and helped train teachers so that they were able to address the particular needs of those older and more mature students who were reintegrating themselves into the educational system.

We also tied the education program into the infrastructure program and began to repair schools that had deteriorated or been damaged. We also began to construct schools in areas that had never had schools before. Rehabilitation of schools, constructing security barriers around them, and the installation of gender-segregated latrines were all factors encouraging more girls to attend school.

Health sector needs were enormous and the limited data available indicated how dire the situation was. One out of every four children died before the age of five. Prenatal care was virtually nonexistent as was most preventive health care. Health facilities in the larger cities were dilapidated and lacked trained staff, adequate facilities, pharmaceuticals, and financial resources. The situation in smaller cities, towns, and rural areas was much worse, with many clinics having closed or operating without trained personnel with few medicines available. The average life expectancy in Afghanistan was among the lowest in the world. Fortunately, many foreign NGOs quickly initiated or reactivated programs in the face of a public health sector that was largely incapable of acting with any financial or other resources. Many of the NGOs brought significant resources with them, including medicines, personnel and financing for facilities and staff, and training. We capitalized on the presence of NGOs and fostered a working relationship between them and the Ministry of Health. Under this arrangement, the ministry set broad policy objectives, standards, and operating protocols, and NGOs went in to implement activities under ministry guidelines. Initially, the ministry would provide staff and manage larger urban health facilities and hospitals while NGOs concentrated on the rural areas. This avoided recruiting a large new public sector service delivery cadre. Very early in the program, we financed the provision of large quantities of pharmaceuticals and vaccines so that the health system could try to make up for the years of failing to provide the minimum vaccines needed for infants and children as well as youth and others that had not received preventive medicines at an early age.

Using our infrastructure projects, we began to construct or repair large numbers of hospitals, clinics, and other health facilities. Like our work in the education sector where we wanted to have a major impact quickly, we did the same in health and we greatly expanded the number of NGOs receiving grant funds.

We also developed a very robust and multi-faceted civil society, rule of law, and democratic development program. Getting independent information out was one of the priorities that we had. One of the first things OTI did to free up the information space and ensure that Afghanistan’s citizens were aware of the political changes that were occurring was to provide radios. At AID Administrator Natsios’ request, OTI purchased eighty thousand radios just after the fall of the Taliban and distributed them throughout the country. This was an early, quick demonstration of U.S. interest in open media and helping people be better informed. OTI had done yeoman work initially in identifying and assisting mass media and helping train media workers to carry out their work in a democracy. The only nationwide information source was from official Afghan radio, but private radio and TV stations were at the point of initiating independent broadcasting. OTI helped establish private television and radio stations and began work training journalists and technical training personnel involved in these news institutions. Later we expanded our work with private news media, providing equipment to stations, assisting their ability to transmit nationwide, and helping train and establish news and wire services. Along with other donors, we worked with the Afghans on drafting a media law that would promote professional and independent journalism, protect journalists and their sources, facilitate access to information, and guarantee press freedoms.

We supported setting up and managing the first Loya Jirga and ensuring that this critical country-wide meeting had an overall logistical capacity function. Larry Sampler, who later became AID’s director of the Office of Afghanistan and Pakistan, came out and managed that process very successfully. This meeting was very important as it was called for in the Bonn Agreement, and established the new Transitional Government of Afghanistan and elected Hamid Karzai as president.

Q: Right.

BUCK: Setting up the site, getting the tents, arranging security and managing the whole overall logistical setup for the first Loya Jirga was part of the effort that Larry led. Subsequent to the Loya Jirga and once a Constitutional Commission was established, we became involved in providing assistance to the Commission with counsel on constitutional practices in other countries and international standards that applied to most constitutional structures elsewhere.

Another democratic development activity was ensuring that the infrastructure was in place for the development of civil society. This entailed the drafting of a framework law that would govern the legal structure of private, voluntary organizations, provide them with overall protections, and facilitate their operations through the commercial banking system. Besides drafting the decree and securing endorsement both within the government and the NGO community, we helped in getting the law adopted, ensuring that proper implementing procedures were put in place, and setting up an overall facilitative process and environment whereby civil society organizations could develop. We also worked with the Ministry of Justice to try to get the ministry itself staffed with capable personnel. We assisted the ministry in holding a large series of training conferences for court personnel, judges, and lawyers. A significant portion of the training was directed toward understanding the new constitution and economic governance structure and their legal ramifications, but also training was provided for lawyers and court personnel that had not received any refresher training in years

Q: Let me ask a few questions. When you arrived there and worked closely with the embassy and obviously Washington, was there a lot of talk or was there any talk at all in terms of U.S. government policy looking to the future of our relationship in Afghanistan related to state building? Was there discussion that that was something because a lot of what you were doing, capacity, institution development, capacity building, new institutions, new laws, like you said, tabula rasa, you could kind of term state building? But was there discussion of that? Was there acknowledgement that it wasn’t just fighting terrorism, it wasn’t just kicking out al Qaeda, it was also helping Afghanistan rebuild after all those years of civil war?

BUCK: This is the same dilemma that I faced in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Uganda, and to some extent in Montenegro and the Central Asian republics. The United States goes in and may or may not intervene militarily and then sets up a USAID mission but hasn’t faced these issues. The USG hasn’t thought through what the end state is or should be. It hasn’t asked the question: what do you want to see so that you can declare success and leave? And so, in none of the countries where I helped set up new USAID missions did we have clear guidance and understanding of what we as the U.S. government wanted to accomplish. Initially, we focused on the most consequential development issues constraining future growth. Then we incorporated other urgent needs and sectors, and later we were encouraged to address someone’s special interest. If budget resources were available, the program seemed to grow like topsy. We’re told to do something, that we’ve got to be involved and so we need to have an impact. But, we’re never given an idea that we’re going to be there for three or five years, so you can focus on something that can be accomplished in that timeframe.

Q: Right.

BUCK: Once you’re involved, I think the perennial issue is how do you get out and when do you get out, but initially, it’s never guidance that you’re going to be there for three years and that’s it. So, focus on things that can be accomplished in that limited period. But of course, the issues that we were dealing with in Afghanistan were the longer-term institutional developmental issues that you can’t do overnight. I think that if I were told that we were to have a three-year program, get in, get out, it would be drastically different. Not having done so, I’m not really sure off the top of my head that I could think what we should really do under those circumstances. But no, back to your question, there was no time frame, final objective, or finite amount of resources ever assigned to us. Given Afghanistan’s precarious development situation I think by osmosis and AID culture, we always assumed our program would be long-term and focused on systemic change. But this was never explicitly stated. In fact, the best guidance we got was in President Bush’s April 2002 George C. Marshall speech at VMI. He said that we must work to make the world better; that we would give the Afghans the means to achieve their aspirations; that peace will be achieved by helping Afghanistan develop its own stable government; that we will work to help Afghanistan develop an economy that can feed its own people; and that we will help the Afghan people recover from the Taliban. That was certainly a call for a comprehensive program aimed at long-term systemic change.

Q: At the time you were there, 2002 to 2003, were you able to travel, to provide oversight, to get out to see project sites and not only you, but your team, some of the other USAID folks?

BUCK: Yes. When the program got underway, working in Afghanistan was much like working in a normal high-threat post. We were able to walk around the city, we were able to travel in unarmored vehicles, and we were able to go out into the countryside. Unfortunately, our office was in the old embassy building and we were all housed in the embassy compound. We were able to move around but the Embassy suggested that when we wandered around the city that we go in groups of two. I personally usually walked alone from the embassy to the palace to meet with Dr. Ghani very frequently early in the morning. We traveled in unarmored vehicles without Embassy security to the Salang Tunnel in the north. We stayed overnight in Mazar-i Sharif, Kandahar, and Herat in private houses with nothing more than the usual Afghan night watchmen. Our contractors and NGO grantees at first lived in privately leased quarters with little security and traveled in regular vehicles. They traveled outside Kabul with no problems initially. My wife worked for the UN [United Nations] in Kabul and lived in shared housing with other UN expats in fully unsecured locations. Office space for most expats was unsecured beyond offices normally being in walled compounds, the norm for Kabul.

During the close to two years I was there, the security situation deteriorated significantly. Our own security posture changed frequently as it became stricter [and more onerous]. We went from, as I said, freedom to wander around the country to have to move around in certain areas only accompanied by “shooters” [shooters were armed Diplomatic Security agents]. Then a new policy required making special arrangements with the Security Office if you were going to be outside the compound in the evening. Later, we had to provide an itinerary as to where we were going. Then, we moved to having to travel in armored vehicles. Then certain areas became off limits, such as Chicken Street, except for special exceptions. We further established a policy that you couldn’t travel into the countryside without prior notice and without traveling in an armored vehicle. Then, several weeks later, it changed so that you had to go with shooters.

Q: Oh, wow.

BUCK: So, you had the security people that would be armed in the vehicle. And then later, I think requirements were tightened even further. We had to not only have the security office go out initially to the area or office to be visited, survey the site, station its personnel there when we arrived at the site, and we had to travel in a convoy of at least two or more vehicles. So, over the course of the time I was there, we went from being fairly free to move around to what you would expect in a critical high-threat post. And you know, we had incidents that would give us an indication that our increasing restrictions were probably the appropriate thing to do. We had rocket attacks directed toward the embassy, but they never actually hit within the compound. A car bomb exploded along the wall of the compound while I was there. We had a couple of Turkish subcontractor engineers working on the road project who were murdered just as road activities were being launched. So, security deteriorated fairly quickly, and we modified our posture accordingly. Virtually all the increasing security restrictions were vetted through the Emergency Action Committee of which USAID was a member and authorized by the ambassador. I personally attended a short daily security briefing on countrywide issues given by the U.S. military. I met frequently with our implementing partners to keep them informed of any changes in the embassy security posture and urged them to act accordingly. Our partners beefed up their security posture significantly over time. When I left in the fall of 2003 most of our contractors and grantees would travel outside the main cities without any documentation tying them to the U.S. government in case they were stopped by the Taliban.

Q: Yeah, and while you were there, who was the ambassador and how were your relations with the State Department? Were there, at the time, lots of other U.S. government agencies, or did that come later? How was the interagency working?

BUCK: When I arrived, Robert Finn was the first ambassador in Afghanistan since 1979. He was great to work with. He’s a Turkish expert and Turkey was my first post. We were probably one of the only U.S. diplomatic posts where the ambassador and AID director both spoke Turkish. I enjoyed working with him and he had considerable experience in the region and Middle East in addition to being the ambassador to Turkmenistan. The DCM [deputy chief of mission] for most of the time I was in Afghanistan was a Farsi specialist with considerable experience in the region. At first, there were few other agencies at post, and State was limited to the security and management sections along with a couple of political officers. There were no economic, narcotics, public affairs, commercial, or consular officers. Early on the DEA [Drug Enforcement Agency] was the only other public agency at post. The military was present in four different forms. One was the civil-military assistance function, the CJCMOTF, which stood for Combined Joint Civil Military Task Force, which was loosely attached to the ISAF command. The second military presence was from the U.S. contingent in ISAF, the International Security Task Force, which was the primary security force in Afghanistan until NATO took over in August 2003. The third group was the Defense Attache office equivalent, though it also focused on training Afghan security forces. The fourth was from the army guard contingent that helped secure the Embassy compound until they were replaced by the Marines in mid-2003.

In mid to late 2002, Washington advised us that it would be sending an assistance coordinator to Kabul. This caused us some trepidation as I had worked with a presidential-level coordinator at another post, and it had caused major disruption to the AID program with little benefit. We were later pleased to learn the official assigned was Bill Taylor, who I had worked with earlier when he was the deputy and later the head of State’s Office for Assistance to Europe and the Newly Independent States. In Afghanistan, Taylor was helpful in our efforts to continue pressure on the Japanese to follow through with their assistance to the Ring Road and in ways we thought were most helpful. He also worked on mobilizing resources for the road from Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States and in encouraging Washington to continue to push other donors to contribute to the Road.

We had a country team meeting, as I recall, every morning, and this was attended by most embassy officials. This gave us the opportunity to understand what the priorities were for other officers, which was mostly political-military issues. It was a good opportunity to get a quick daily security briefing and to learn about the plans and schedules for the agonizing stream of visitors that we had and expectations for USAID participation in the visits. Now, at that point Zalmay Khalilzad was in Washington as the point person for Afghanistan at the NSC [National Security Council], and we understood that he was the one that President Bush looked to for everything about Afghanistan. Khalilzad came out to Afghanistan, I would say, at least every three to four weeks, spending three or four days in country meeting with Afghan officials. Frequently he did it without someone from the embassy in tow and would leave it to others in terms of the feedback that we got on what was discussed and what the issues were for others to follow up on. During his first trip to Kabul, I gave him a full briefing on the dimensions and direction of the USAID program. He generally concurred with our approach and had no suggestions for any changes. Subsequently, I met with him probably every other time he came out and went with him to a number of meetings when he met with government ministers. I happened to be back in Washington on medical leave in the summer of 2003 and I heard the rumor that he would be coming out to replace Finn as ambassador. When I got back to Kabul, I went to the Ambassador and told him that I had heard he was going to get the ax and that Khalilzad would replace him. Ambassador Finn feigned ignorance of this, saying something along the lines of, “That’s a surprise; I had not heard that.”

Q: Oh, no.

BUCK: Yes. So, anyhow, Khalilzad arrived sometime shortly after I left.

Q: I see. And how were decisions made? I mean, you talked about the development sectors where initially got engaged in five areas, and you know, whether it’s a new Central Bank, how that should be set up or a health system, there’s a lot of decisions to be made and policies to be established. How were decisions made in these areas as USAID got going?

BUCK: From the beginning, we had superb backstopping in Washington, and to me that was critical to ensuring that the program we put together in the field was understood, endorsed, and supported. Bernd McConnell was the initial chief of the office handling Afghanistan, which Administrator Natsios had set up shortly after 9/11 as a special unit reporting directly to the AID front office. We always had rapid access to AID’s Front Office if we needed it and could get through quickly to Administrator Natsios or later his deputy, Fred Schieck. Jim Kunder, who came to Kabul at the very beginning and began the humanitarian activities, was also key as he became acting AID deputy administrator for an extended period.

But a group of people that McConnell recruited, primarily Nitin Madhav and Jeanne Pryor and later joined by Jim Bever, provided the depth, the continuity, the Washington-field communication that was so critical, and the sense of urgency that often motivated other offices to move on field priorities. They were invaluable in giving us feedback on Washington concerns and on issues we needed to anticipate pushback or questions. And, their judgment was very discerning, always letting us know which Washington concerns we could blow off and those we genuinely needed to give attention to. They really did most of the heavy lifting that we needed to make Washington aware of what we were doing and handling the interagency issues. I always felt that we had real support there. Keeping communications open with Washington took its toll. We had an extended daily phone call with the Washington office that began just at the end of our first twelve-hour shift in Kabul, and almost every day, we ended up having to prepare multiple briefing papers, responses to questions, background notes, and other documents to feed Washington’s insatiable demand for information.

Besides the superb assistance from the desk, several other AID offices were quite helpful in getting the program underway. They moved the bureaucracy to approve major exceptions to normal practice to authorize projects, secure contracts, waive standard practices, and meet legal requirements. Washington came up with both program and operating expense funds, some of which came from dipping into the agency’s existing budget and required significant reprogramming. Other resources came from supplemental funding that AID invested significant time, energy, and credibility in getting urgent new appropriations. Several offices made key officers available to come to Afghanistan for extended TDYs [temporary duty] to help on project analysis, authorization, and implementation. Washington also issued two grants very early in 2002 to jumpstart activities in the education and health sectors.

The only issue that I think we did not get adequate support for was the construction of USAID office space and housing. The AID space in the old embassy building consisted of two offices, approximately fifteen by fifteen feet. We crammed fifteen to twenty people at a time as we initiated the program. Clearly, this was unsupportable. Similarly, we were housed like the rest of the embassy staff in one-half shipping container-like accommodations called “hooches.” Because there was a limited number of hooches we were greatly impeded in project development, implementation, and accountability by this space limitation, as we could not bring out the support staff needed.

We proposed constructing an AID office and housing on a large compound across the street from the embassy that we learned could be made available for long-term lease. We had an officer on board in Kabul that had constructed housing and office space for AID and the embassy in record time in Central America, Bosnia, Kosovo, and Montenegro. I knew that if we provided the financial resources he could meet and needs within a year. The Ambassador sympathized with our needs but told me we would have to be responsible for getting Washington approval. We never got a clear negative response to our request to move forward by AID Washington. Our request at even AID’s most senior levels were always met with dilatory responses such as, “We need more info; we need to socialize it around; what will State think; can you really do it; can’t we wait for OBO, et cetera.” I visited the embassy eight years later, and USAID was still in temporary office space.

But, back to your question about policy decisions. I never really felt that we needed significant strategic policy guidance from Washington or that we would get it. As I said earlier, after I made the rounds in Washington just before going to Afghanistan I did not think that I got specific direction on what we should focus on and what we should accomplish. Once we pulled together an outline of our program, I made certain the ambassador was on board and discussed it with Washington at length and at all levels of AID. Of course, we made modifications in the program as we went along and got feedback as well as a better understanding on the ground and with our Afghan counterparts. Feedback from Washington on changing budget projections also influenced our plans. We were always open to discussing our program with Washington and entertaining any suggestions, I do not ever recall any contentious programmatic issues with Washington beyond the logistical support issue. One of the reasons we did not need Washington’s input on the program is that we ensured that management of programs and grants was delegated to the field. At first, we did not have the staff to manage the contracts, but as we recruited new officers, we were able to manage projects in the field. Having shared our programmatic approach and having kept Washington informed at length as we began to operationalize the program, we did not call on Washington for programmatic decisions. I’ve always felt that if we make egregious program errors, they can find someone else to run the program

While this may sound insensitive to Washington oversight, I had great confidence in the few staff members that we had in the field. All of them were extremely competent, experienced, and comfortable with the 24/7 work pace we had. They all had significant high-level experience conceptualizing and implementing the programs like we developed. We brought out the most qualified experts that AID in Washington could make available to assist us. And, the contractors that we managed had long-term expertise in the programs we managed. Of course, we called on Washington experts for assistance as problems developed, but we took the initiative and did not pass difficult decisions back to Washington to second guess. In the end we are AID development officers and we’re paid to understand those things. We’re the ones that should have that knowledge without having to refer everything to Washington.

Q: Yep, that’s right. I’m just thinking, were you, before you left Afghanistan, engaged at all in any of the counterinsurgency and AID’s role, discussions around counterinsurgency and USAID’s role in that some of your successors had to deal with?

BUCK: Well, if you are talking about the PRTs [Provincial Reconstruction Teams], yes. We had been in touch CJCMOTF from the beginning of our program. CJCMOTF basically was the on the ground military civil affairs unit in Kabul that had initially focused on humanitarian assistance work. CJCMOTF officers were interested in the AID program, how we worked, how we operated at the local level, what relationships we had with local authorities, how we provided security, how we managed funding, et cetera. I gather this information helped in their preparing the PRT concept.

When I was in Bosnia, we had initiated a program called the Community Infrastructure Reconstruction Program [CIRP] that integrated military operations and interests with those of AID to serve our foreign policy interests. In the CIRP program the military identified projects that would demonstrate their concern with economic, social, and policy issues that they had on the ground. Carrying out these projects the military thought would ingratiate them with the local community and further the community’s interest in working with the military. This would help achievement of Dayton Peace Accord goals of ethnic reconciliation and the return of minority groups to areas where they had been expelled. Once projects were identified the military wanted AID to come in, finance the activity, and ensure that it got implemented. The military would come in periodically to monitor implementation and associate itself with positive activities benefiting the community. This program worked really well, but it was not without its problems, but I think that AID brought a lot to the table.

We didn’t think just of grabbing a project, constructing things and then leaving. Before becoming involved, we wanted to know who the project was for, what investment the community was going to provide, who were the real the benefactors, who politically was going to benefit, who was going to maintain the project and provide operating costs in the future, was it cost effective, i.e. the whole gamut of accountability issues that AID would normally look into. More importantly, we wanted to ensure that projects met our broader reconstruction program objectives. That is, the projects should generate employment, should facilitate longer-term growth, should not impose continuing costs outside the community, should facilitate the return of minorities, should have a large community input during implementation, and should be undertaken only in communities that were actively complying with Dayton Peace Accord objectives. Oftentimes in Bosnia we had problems with projects the military proposed, but we overcame them. We talked them through. And the military began to understand where we were coming from, and we could understand the military need for showing boots on the ground and that something can be done. But the program was not without problems.

In the case of Afghanistan, AID Washington as well as the military in Kabul kept asking us to bring out personnel, to insert them into the Provincial Reconstruction Teams [PRT] that the military intended to set up throughout the country. The concept went from an initial team that they had in Gardez to a country-wide program in which they needed AID personnel on the ground in the PRTs to focus on development issues. We had major concerns with the as yet ill-defined PRT concept in the spring and summer of 2003. For some months, the CJCMOTF had been presenting us with a draft memorandum of understanding covering mutual responsibilities under a PRT-like program. We had never been fully briefed on the scope of the program in Kabul in spite of the fact that we had been working closely with the civil affairs officers in CJCMOTF from the beginning. In the field, we had been working with the military CHLCs [Coalition Humanitarian Liaison Cells] in several areas. The CHLCs were civil affairs teams that were operational in several sites and were carrying out humanitarian assistance activities with local communities. We understood that the military intended to complement and replace the existing CHLCs with PRTs, which would be much more robust in terms of personnel and financing.

It was not clear to us what the PRTs were expected to accomplish and the timeframe to do it. I had no idea of what the end status of the work was expected to be. The AID-military activity would be carried out in a kinetic environment that was sharply different from the circumstances in Bosnia. In Afghanistan we would be working in a situation without the language qualifications and cultural knowledge to understand the political and social dynamics in areas that already were deeply suspicious of us and our motives. Trying to do this in areas where we were also carrying out active military operations that directly affected the people we were going to try to help, I thought was not a good use of resources––financial, managerial, or intellectual. Besides not having a full picture of the dimensions of the PRTs there were myriad implementation problems that needed to be addressed before putting AID personnel in the field. These included such things as AID and the embassy’s role and responsibility in managing personnel under military cover, financing for activities, managing conflict and differing priorities, the role of NGOs and contractors in project identification and implementation, and rules for working in areas that did not acknowledge Kabul authority. In spite of our concerns, I was told, in effect, that AID Washington had bought into the PRT concept and that I had to implement it. I was told that as a priority, I had to recruit the people to serve as the AID representative in all PRTs. From the beginning, I didn’t have enough people in my office to do the billion-dollar-plus program that we were trying to put together and execute. I really felt that I was having something imposed on me and was told to do it immediately. From my perspective, it was just like being told, “Craig, you go get the personnel and you put them in there without asking questions.” I had major concerns but this was the only time that Washington said in effect, Do it and stop arguing.

Q: And were you able to put in place some understanding with State and DOD [Department of Defense] on the role of various agencies, USAID and State in the PRTs?

BUCK: No. I left at the point where the first one had been set up in Gardez [without AID], and they were trying to recruit people for the others. And we were dealing with those issues when I left; at that point it was time for me to go. So, I left it to Jim Bever to take care of. (laughs)

Q: So, Jim Bever replaced you as mission director?

BUCK: Yes. I left and Jim came in periodically for an interim, I think for four or five months and then a permanent replacement came to Kabul. I don’t recall who came after Jim.

Q: Yes, I think Patrick Fine.

So, what would you—what are your insights and reflections? I mean, this is twenty years ago, there’s been a lot, obviously, happening in USAID, U.S. government role in Afghanistan. You’ve read a lot. I’m sure you’ve kept up to date on what’s going on there. But your few years there were instrumental in both setting up the government of Afghanistan, the institutions of governance, like you said, economic governance, of a democratic economic governance. And what are your reflections looking back from that time when you were there?

BUCK: I wish that we had done more to improve the role of girls in society. We had a major impact of getting girls back into school, getting women into the workforce, and helping women become an element of civil society. But, in retrospect, I really wish we could have done more. However, in the end, that collides with the problem that Afghanistan is a very patriarchal society, and certainly, perhaps it’s not our business of really changing the way that a society functions and values people and things. But I think we could have, if we had the luxury of personnel, time, and resources, we could have done more in the way of getting women accepted as full participants in Afghan society. I once had a law professor that used to say that we can’t legislate how people think, but we can change the way they act. Here we needed to change how people behaved.

Another area I’m disappointed in, we had minimal impact that apparently did not survive the Taliban return, was in the development of civil society and the rule of law. Virtually all the areas we worked involved the creation and promotion of private organizations that supported a multitude of causes such as legal associations, school groups and parent organizations, women’s associations, press workers and journalists, bank employees, free speech advocates, university supporters, and worker protection supporters. Our work in getting a modern law on associations that met international standards facilitated the work and growth of these organizations. But with the exception of a few than have protested the treatment of women, it appears that they all have no influence or voice under the Taliban and some have been directly suppressed or banned altogether.

Our work in making the justice sector more effective was also disappointing. In spite of the massive training of Justice Ministry officials, lawyers, and court officials, the wheels of justice always seemed to be too slow. And, they appeared to favor those with resources or influence and did not give confidence to the concept of equal justice under law. I suspect that one reason the Taliban enjoyed support is because it was viewed as exacting justice quickly and without favor.

I think that what we did on economic governance, warts and all, was and is the foundation for how the economy is functioning. The system of commercial and contract laws that we helped develop are the broad framework and system under which commerce is taking place now. The Ministry of Finance became a reasonably responsible institution, able to collect, disburse, and account for funds under the direction of political authorities. In fact, the World Bank system that the international community, including AID, used to transfer resources to help cover government expenses was executed through Ministry institutions and procedures we helped establish. The Central Bank and the commercial banks it regulates operate relatively well and they fulfill their function of mobilizing and investing resources and facilitating transfers. All of this resulted in significant economic restructuring, adjustment, employment, and growth. Now, all of this could be improved, and the institutions and reforms are subject to manipulation, which is another one of the areas that we never got a handle on. That is the venality that permeates Afghan society. But what we consider venal behavior is a culturally acceptable way of operating, so you’re kind of stuck with that.

From what I read, many of the roads we rehabilitated or constructed have deteriorated. I also have heard that many of the schools we constructed have major structural issues, which I understand was due to substandard construction by contractors. Many of the clinics we rehabilitated are only partially operational, but that probably is due to the lack of NGO support and central government financing. I think the lesson is that we needed to give much more consideration to maintenance and recurring costs before launching large construction projects and that community involvement from the beginning is paramount.

At least we can say that for an almost two-decade period, people worked more, they got a fundamental education, got access to healthcare, and most were immunized though things may have fallen apart in the health sector when the NGOs left. There were problems but people were able to live just a bit better. And that, I think, was very important. So, in spite of the problems, I think we did have an overall positive impact in the end.

Q: Absolutely. Just wondering, Craig, were you engaged or USAID in some of the discussions about, for example, decentralization that if I remember what I read, took place when they were talking about the constitution, the powers and the role of the presidency versus kind of a decentralized kind of power structure, and that was one of the criticisms even when I got there it was all run by Kabul. Were those some of the discussions you were engaged in? Also related to that, coming in with ideas of how these institutions, even the constitution should be modeled on the Western versus something that is more Afghan, based on Afghan culture and religion, history and the like?

BUCK: Yes. On the latter issue, we brought in people that could give the Afghans perspectives on how critical constitutional issues were handled in other countries. We mostly didn’t get into the details of the issues they were wrestling with, such as how many people in each house or whether you even had two legislative bodies. Experts that we sponsored were requested by the Afghans to see how other countries dealt with critical issues. We certainly left it to the Afghans to make the ultimate decision and so they were free to pick and choose among the options considered. On most of the issues, we had no particular interest or position, but we were interested in several: ensuring equal treatment for women, for example, and the treatment of religion. Adoption of a tripartite form of government with an independent judiciary was also an issue we followed carefully.

With respect to the center versus the periphery issue, our position was very clear among the few areas where we did get involved and this was not just when considering the constitution but also in almost any other forum when the issue arose. It was clear at the beginning that we supported the supremacy of national over regional authority. With the fall of the Taliban popular regional leaders and military warlords controlled vast amounts of territory and in many areas refused to cooperate with the central government. Many of our efforts were specifically oriented towards helping the central government exercise its fiat throughout the country. This complemented what the government itself was doing to establish its authority. Both in the interim and transitional administrations, regional warlords were brought into Kabul as vice presidents, cabinet ministers, or senior officials. This was an effort to reduce their contact and influence in their area of control as well as to get them to consider national implications of policy rather than just their parochial concerns.