The attack on the American embassy in Tehran on November 4, 1979 and the subsequent 444-day imprisonment of American personnel has become the stuff of legend – it was followed day by day on the news by millions of Americans, many of whom put yellow ribbons on trees and their houses as a sign of solidarity. It was the subject of an Academy-Award winning movie, Argo, and ultimately led to the downfall of President Jimmy Carter. However, most people would be hard-pressed to recall a similarly dramatic attack, which took place a mere 17 days after the attack on Embassy Tehran.

On November 21, rioters, incited by false Iranian radio claims of an American attack on Islamic sites in Saudi Arabia, stormed U.S. Embassy Islamabad, trapping more than 130 people inside the communications vault for several hours. Several people died, including one young Marine Security Guard, Steve Crowley; the entire embassy was burned and eventually had to be rebuilt (with money from the Pakistani government).

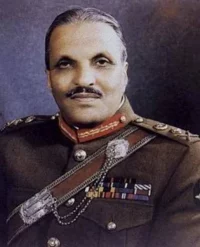

Normally, communication with a country’s leader would be the most important step in assessing such a situation and attack on a foreign embassy. However, in this case, Pakistani President Zia al-Haq was unreachable, as he was out in the countryside riding a bike. The siege of the embassy grounds lasted for hours, as the army was delayed or simply was not ordered to rescue the American diplomats and staff trapped in the embassy’s vault.

Barrington King was the Deputy Chief of Mission at Embassy Islamabad. Throughout the siege of November 21, he worked frantically with the host government to get them to respond. Herbert Hagerty was one of the embassy employees trapped inside the vault. King was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy beginning in April 1990. Hagerty, Political Counselor at Embassy Islamabad from 1977-1981, was interviewed by Charles Stuart King beginning in July 2001.

Go here for other Moments on embassy security. Read other Moments on Pakistan, including about the bureaucratic squabbling behind rebuilding Embassy Islamabad.

“Stay where you are. There’s a crowd marching on the Embassy.”

Barrington King, Deputy Chief of Mission, 1979-1984

KING: Now this is not the greatest disaster we’ve ever had now, but I think at the time it happened, it probably was in the whole history of U.S. diplomacy. As far as I’m aware, it’s still the only incident of an entire embassy being destroyed — I mean everything.

The way it came about was that…of course relations with Iran were a problem because there is a large Shiite minority in Pakistan. They were very antagonistic towards us because of our relations with Iran.

The day before Thanksgiving…’79, a group who later turned out to be Shiites, seized the Grand Mosque in Mecca and were driven out after a great deal of bloodshed and trouble by the Saudis.

That was broadcast early in the morning, and I’ve never quite got the story straight…and it’s a little murky. Somebody alleged, probably the Iranians, who may well have been involved themselves — probably were — that the Americans and Israelis were behind this sacrilege.

Now you’ve got to understand how things are in Pakistan. It’s an emotionally volatile place, and once when the Italians made a film about Muhammad, or were going to make a film about Muhammad, an army of people marched on the Italian Embassy to burn it down, and it took the Army to turn them back. This is something we get from the newspaper. It’s easy to stir up this kind of situation. You have a large, very poor, very ignorant population, very religious and emotional, and if they’re Shiite, then it’s in spades.

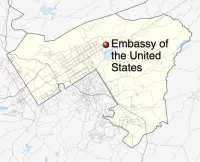

We were not too concerned about security because, like Canberra, Islamabad is an artificial city. It’s built out in the middle of nowhere, it has no urban population, it all consists of diplomats and bureaucrats. There’s no industry, there’s nothing. So the government didn’t take security there too seriously. There is, however, about 20 miles away a major population center in Rawalpindi.

I guess, the way they felt was, or they later claimed, that given the topography of things, a large crowd could hardly walk through this landscape 20 miles to do anybody any damage, except of course, there’s this big six-lane highway that goes to the airport and then on to Rawalpindi. So all you really have to do is just close the road.

The problem is they didn’t close the road. The word got about, and somebody…said that they should go and avenge themselves on the Americans by attacking the American Embassy. We didn’t know any of this at the time, of course.

Rawalpindi is one end of a truck route that goes to the Khyber Pass, and these big trucks, old fashioned vehicles, go in large numbers back and forth between the Northwest Frontier Province and the Punjab. And in Rawalpindi there’s a big market area, where on any given day you find hundreds of these big trucks which are offloading one thing, and are taking on something for the return journey. So what happened was the mob got the truck drivers to take them to Islamabad, and they came in the thousands….

“The wall didn’t stop anybody long. They just drove the trucks right through the wall.”

I was driven home. I’d been there about 15 minutes when I got a call which said, “Don’t come back, stay where you are. There’s a crowd marching on the Embassy.” I did that, and quickly discovered that the Ambassador [Arthur Hummel] was also at home for lunch.

Just by some fluke out of 150 people who were in the Embassy that day, only maybe five people were outside the compound when this happened.

It was a big brand new Embassy. It cost $23 million. I know because that’s the claim we put in, and around it it had a big brick wall. It had bars on the windows, and it had big sliding metal doors, and a lot of things like that. It was reasonably good security, not the best, but given the situation we probably didn’t concentrate on that as much as we would have if it had been in downtown Rawalpindi.

In any case, the wall didn’t stop anybody long. They just drove the trucks right through the wall.

There was good coordination inside the Embassy. The Administrative Counselor, and the Political Counselor, and a couple of other people led things. They locked all the safes, and retreated into the vault. The vault was on the top floor, it’s a three-story building. The Marines were positioned outside, eventually they all retreated into the vault.

There was one Marine up on the roof keeping a lookout, and he was killed by someone who had a weapon. It may be that they had weapons, but they overpowered the police detachment, and took their weapons from them, and they may have used those.

“Into the Vault”

Herbert Hagerty, Political Counselor, 1977-1981

HAGERTY: The embassy remained at full strength, so when it was attacked and we retired for safety to the vault, we numbered 137 or so, 50 Americans and 87 Pakistanis, not counting others who were on leave, at the American Club, or otherwise occupied.

We had exercised that drill previously, and we had also held meetings with the resident American community in the embassy auditorium to calm their fears and try to what we were doing and what we were talking to the government about.

We were in touch with every level of the government. The Ambassador, who was a mile away at lunch in his residence, was in touch with the [President] Zia’s office and the Foreign Minister by phone. The DCM was also at home at lunch. This was the routine.

The only reason I wasn’t home for lunch was that I was planning lunch at the Embassy with the Time Magazine correspondent, who had just arrived from Delhi.

At the time the first crowd came, I had told her to go to the cafeteria and just wait for me until we dispose of this demonstration. She eventually spent the entire afternoon with us in the vault.

Well, as it played back to us, what we were hearing from them was virtual disbelief that this crowd — that a crowd of this size — had formed at our gates. You know a rush hour traffic jam in Islamabad in those days was five or six cars. Islamabad wasn’t a highly populous area. We could normally look out windows and see women washing clothes in a stream or cows wandering across a field. I mean it was that kind of rural atmosphere. So the notion of a determined crowd of 10,000 suddenly appearing was hard to accept. And of course we could not see them.

The Pakistanis had increased their police in the area at our request earlier, and in fact there was a contingent of 24 armed police officers on our compound. But, they were overwhelmed, afraid or reluctant to use their weapons to face down the mob.

We went into the vault and bolted the door. We could withstand them, essentially give them the building –stay in this secure area. We were confident that help would arrive with the Ambassador on the outside and the phones working. We were talking to the Ambassador on the phone, talking to the DCM on the phone; I was talking to the Foreign Ministry, but help didn’t arrive.

There was a brigade of troops – 1500 or more soldiers — in Rawalpindi where they had been on a parade-drill that morning, but that was 20 miles away. They had just been dismissed at the end of the drill, making their way back to their barracks on their own. They were not marching back, so they were essentially not recallable and never did turn up in Islamabad….

People were sitting on the floor. The building outside our vaulted door had been filled with tear gas by the Marines. The chancery had both front and rear entrances, and in response to attacks on other U.S. missions elsewhere in the world earlier that decade, the front entrance had been made impregnable. Plans called for the back entrance and the cafeteria windows to be made impregnable by the end of 1979, but that’s where the rioters came in.

We decided to order the Marine at the post near the back entrance to come to the vault, but it was dicey. I got instructed him by phone to try to join us. His only alternative would have been to exit through the door, where he might have been torn apart. So, he agreed, and I recall hearing one determined shout on the radio that sounded like, “Up against the wall, you…” He had on a gas mask and had a shotgun in his hands to protect himself, if necessary, and no rioter attempted to stop him. And we happily opened the vault to let him in.

“We breathed through wet paper towels, most of us sitting on the floor, trying to do what we could to keep people from panicking”

From there onward, we spent our time talking with the outside by phone and radio. We learned that there were problems at the American International School, two miles away and tried to learn more about that. Later there was a bit of a riot there, too, and we all worried about our kids. The day just dragged on and on.

Then about 3:00 in the afternoon, we heard a helicopter passing overhead, and we all hoped that meant rescue might be at hand. We had already checked the blood types of various people in the vault and had two volunteers ready to go with the wounded Marine if we could get him air evacuated off the roof.

The helicopter was an army helicopter that apparently was just there for observation and wasn’t prepared to try to land. We were then aware also that there were rioters on the roof, and they were working on the hatch above our heads that was going to be our escape hatch if we ever got out of there. We could hear them pounding on it. They were also firing shots into the air vents so we could hear bullets whizzing through the ventilating system. That noise was compounded by the fact that we were breaking up commo [communication] equipment in the other part of the vault. There was a lot of sledge hammering going on there.

“Despite the nurse’s efforts, the young wounded Marine with us had died”

Then we began to get a lot of smoke, so we realized the building was on fire. The nearby British Embassy told us by phone they could see that the building had been set on fire. We got a lot of tear gas as well. We had one air conditioner working in one room of the vault that continued to work throughout, so we took turns rotating people in by that air condition to get some fresh air, but for the rest of the time, we breathed through wet paper towels, most of us sitting on the floor, trying to do what we could to keep people from panicking, and at the same time making sure that the people outside knew that our condition was increasingly perilous.

Meanwhile, despite the nurse’s efforts, the young wounded Marine with us [Steve Crowley] had died in another small enclave of the vault. Those of us in charge kept this news from being known by the others at that time, and in view of later developments that was a wise decision.

A little later in the day, the floor began to be pretty hot. The temperature inside was rising because the fire was beneath us, and this was after all a vault. The carpet began to smolder in the corner, at which point one of our very youngest and a young female FSN was just beginning to wail…you could just hear her. It was going to be the start of a huge panic for her. Almost at the same moment, another FSN, a most grandfatherly gentleman, the only guy in the room who could have done it, went over to her, put his arm around her, soothed her, and she stopped.

Luckily, there was no other sign of panic at all. The person who reported the smoking carpet was my secretary who was sitting over there, and I just motioned to her to come away from the corner and go find another place to sit.…

We had lost our capacity to communicate by cable after about an hour into the vault, and later the phones went out, leaving us with just our emergency two-way radio on a circuit with the British Embassy, the Canadians, the school, the Ambassador’s residence, and the DCM residence. The DCM had taken up station by that time at the Foreign Ministry at Ambassador Hummel’s request, so that he could be putting his pressure there. Hummel, of course, was on the phone to Washington, to Zia, and to others in the Pakistan Government.

“President Zia, however, was in Rawalpindi, and he had taken to riding bicycles, and he was having a bicycle ride”

KING: There was a Warrant Officer [Bryan Ellis] who went to his apartment, because we had 30-35 apartments in the compound. He went to his apartment and locked himself in. Two of our FSN [Foreign Service National] employees locked themselves in their office rather than going to the vault. All three of these people were killed by smoke inhalation.

What the mob did, and you know, motivations were different as they are with mobs, after it was all over we noticed that not a single typewriter was any longer there, no liquor was left in the American Club, not one bottle. So some people just came to loot. In fact, they stripped the Embassy of everything.

But in the process, there were about 80 cars in the parking lot, they drained the gas tanks, and took gas in buckets, put it all over the Embassy, and set it on fire.

It’s not that an Embassy is particularly easy to burn, its masonry and brick, and there’s not a lot of inflammable stuff, but if you use enough gasoline you can make anything burn. So it wasn’t long before the whole Embassy was aflame.

I was on the telephone with the Ambassador, and we agreed that he would stay where he was. He had radio contact with the vault. I had a radio in my house, and my wife sat beside the radio for the rest of the day, and transcribed everything that was said. It’s the only record of what happened. I got in my car with my driver and made a loop around to avoid the crowd to get to the Foreign Ministry, which is very close to the Embassy, and luckily didn’t run into any of this mob.

I went straight up to the office of the Secretary General of the Foreign Ministry (left), and that was about 12:45 or 1:00, where I stayed until the whole thing was over. He and I together called various people, including the President, the President’s chief military aide….

President Zia, however, was in Rawalpindi, and he had taken to riding bicycles, and he was having a bicycle ride, and he was greeting his constituents.

I think the non-arrival of the Army for the next five hours is very suspicious. You could even say, I think legitimately, that they were taken by surprise by the suddenness of this rush down the highway that they could have stopped if they’d had an hour or two warning. In any case, I think most people involved found it very suspicious that they didn’t do anything….

The response was unsatisfactory, to say the least. Some people explain that they wanted to teach us a lesson about a few things. Others that they didn’t want to get involved until they absolutely had to because that meant shooting Pakistanis, because that’s the only way you can control a mob in Pakistan. You just have to kill people. Or that they didn’t realize it was as bad as it was.

Anyway, from the Secretary General’s balcony of his office, you could see this huge column of black smoke going up into the sky. I mean, there was no question how bad it was. And you could also see the road, and you could see truck after truck after truck of these yelling, chanting people. I guess we probably got about 10 or 15 thousand at the height of this thing.

Finally, and this took some time, we got Army helicopters but by that time there was so much smoke — the idea was to land on the roof, one at a time, and take off with a load of people. They couldn’t see where to land, and also — and this is legitimate — they weren’t sure what the roof would hold. It’s nothing I was an expert on. I had no idea either. My guess was that it wouldn’t be a problem.

In any case, they never landed, and I think, also, there was some concern that they were going to be shot at too. This situation went on, and on, and on. I would talk to the Ambassador [Arthur Hummel, pictured]. He would talk to the people in the vault. We’d try to get somebody to do something.

By that point the police were no use at all, you had to have regular Army to have any hope of saving people. About 5:30 in the afternoon, still nothing had happened. The Army was on its way, we were being told then, for some time.

There was a second group of people who were dependents, women and children, who got caught in the compound, and were surrounded by an angry mob, but about a dozen policemen with weapons surrounded them, and there was a stand-off that lasted all afternoon.

The real danger, of course, was the people in the vault. We had all of our American, and FSN employees, in there, including the Time Magazine correspondent who’d been conducting an interview at that time.

About 5:30 it got so bad in the vault from the heat — this building was all in flames — that the floor tiles started popping off. We knew we couldn’t last much longer.

“We agreed to send an armed group up to the roof”

HAGERTY: It was getting hotter and hotter, but the November daylight was also fading. Eventually we got word from the Canadians — a Canadian residence compound nearby that the crowd was thinning and those on our roof were gone.

We could tell also since that there weren’t any noises on the roof. The temperature dropped suddenly as it does in November in Islamabad, often into the 40s. But our eyes were blinded still. All we had was what other people could tell us.

Our Admin Counselor and I – we were the two senior officers in the vault — we agreed to send an armed group up to the roof by a route that the rioters hadn’t known of. So, our Gunny [Marine Gunnery Sergeant] led an armed group including two other Marines with shotguns, an Army major, an Army captain, both under the Gunny’s command, plus one embassy officer who’d been a Marine officer and who was also armed, and one FSN [Foreign Service National, local hire], for Urdu and Punjabi language capability. All were volunteers.

As they got to the roof, they saw the last of the rioters climbing down. The crowd was smaller on the outside. The building was just smoke all over, smoke everywhere. So, they cleared the roof and established themselves in control.

When the rioters realized they had not been able to force the hatch open, it was clear that they had attempted to jam it, so we wouldn’t be able to get out. We’d had four Marines or other people sitting on the floor of the corners of the small room directly under the hatch all day in anticipation that the hatch might go, and they had shotguns pointed up so there would have been bloodshed had the hatch gone. We lucked out on that.

It took a little extra effort to get the hatch opened from the inside, but when finally opened, we could begin to exit. There was so much smoke and so much tear gas that we had to go through a hall where it was thick in order to get to the ladder. We did it five people at a time so that we didn’t have a lot of people just standing there. We sent first the Pakistani women, then the American women, then the Pakistani men, and finally the American men, with our consular officer organizing this line-up and with the Admin Counselor and I part of the last five to climb out.

“He climbed the ladder, got the dead Marine over his shoulder in a fireman’s carry, and carried him out — the dead Marine still dripping blood”

Of course, it was wonderful to be out. There was a clear sky, and I could see the stars. But then I looked around the roof edge and could see nothing but flames. The good news is, I’m out in fresh air, but the bad news is how the hell am I going to get off here?

Well, the Gunny and our Pakistani employees had scouted the roof and found that there was a place with a drop of about ten feet down to the roof of our auditorium. At this point, fire trucks were pulling up to the building, and Pakistani troops were just moving into the compound. Suddenly the whole complexion of the compound changed, and we felt it was safe then to go down.

Several of the Pakistani FSNs, the men, who had stayed on the roof until all the Americans were out of the vault, jumped down to this secondary roof of the auditorium. After that their colleagues on the roof dropped individuals who were then caught by those below. I found myself lifted, dropped, and caught by burly Pakistani FSNs. Others found their way to the ladders that the rioters had used, and we all climbed down to the ground.

I was one of the last down the ladder, at which point I was met by the Director General for U.S. Affairs in the Foreign Ministry, who wanted to take me to the Ministry so I could fill them in on what was going on. I was prepared to go with him, and I had been told to do so by the Ambassador.

But we were all standing at the bottom of the ladder, and we were just sort of in a state of shock to be out of this whole thing and then the Gunny said, “I’m not going to leave my dead Marine in there.” So he climbed the ladder and went back into the hole, got the dead Marine over his shoulder in a fireman’s carry, and carried him out — the dead Marine still dripping blood.

Most of us who were holding the ladder broke into tears at this point, terribly moved by this episode.

He died principally of shock and possibly loss of blood, but I think it was shock more than anything else. If he’d had prompt medical attention, he would have been saved. It was particularly sad. He was out youngest Marine, very popular.

“We figured if [the train with Americans] ever stopped anywhere with this story about, they’d all be massacred”

KING: The Army arrived. And by that time it was beginning to be dusk, and I’m sure they felt there’d be a lot less problem with the Army shooting people in this situation, than in the full light of day. So they got out of there fast.

We were, of course, trying to watch other situations, and I was on the phone to Peshawar, Karachi, and to Lahore. We had a particular concern because we had hired a train. A whole crowd of people had gone down for Thanksgiving to Karachi, and as can be done there, they took a whole train. The train was somewhere between Islamabad and Karachi, and we figured if it ever stopped anywhere with this story about, they’d all be massacred.

By that time the Secretary General had gone to see President Zia (left), who had finally got back to Islamabad. I was with the Chief of Protocol, who is an Army General himself, trying to get hold of the railroad authorities to get that train to some place where it was safe.

At this point, the Political Counselor came bursting into the room, and I had been so totally concentrated on what I was doing it didn’t even occur to me where he’d come from until I smelled smoke. And then I realized that he’d been in the vault along with everybody else because I had no idea who was in there. So we together worked on this problem.

This went on as we tried to get ourselves organized, find out where the people were, and all during the afternoon too I was on the telephone with my wife finding out what was happening, according to the radio, to everybody in town. The school, where my two children were, was attacked — it was not a serious attack — and a retired Pakistani colonel just pulled out a gun and got the people out of the school.

HAGERTY: We were concerned about the kids also at the school. There a halfhearted mob attack had been repulsed by some very courageous people with broomsticks. I had a son there, a high school senior.

But something wonderful happened there, too — it was an international school — and the French military attaché, who had two kids in the school, organized a parental caravan of non-American parents to make sure that every child there was delivered to parents, face to face, in private diplomatic vehicles that afternoon, so that all the kids got out and went home.

Then when I finally finished with the Brigadier, I went to the British Embassy, which had a phone line open to the State Department. I went there at Ambassador Hummel’s request, and as I walked up the steps, the British Ambassador, whom I knew well, greeted me at the door with a very dark whiskey glass full of Scotch. I happily drank the whole glass.

“Our other posts in Pakistan were attacked at the same time”

Then I had a long phone conversation with Washington and went home to see my family. My then spouse, who was head of the consular section in Karachi, had flown to Islamabad that afternoon because this was Thanksgiving eve. She had been driven to my house and had spent the entire event with an open line from my house to the Operations Center in Washington and alternately to the Karachi Consulate, passing what she knew and what she heard on our radio circuit to both.

As you know, our other posts in Pakistan (and elsewhere in the Third World) were attacked at the same time. We lost our USIS [U.S. Information Service] library in Lahore. We damn near lost our consulate and all the people in it too but for the bravery of the two junior officers who took control and toughed it out. Our consulates in Karachi and Peshawar were threatened but were protected by timely police actions that interposed between the consulates and the crowds. A lot of other Western symbols were burned also.

So by the time everything sort of settled down, the Army by then was there in large numbers. They were all over the city. At every street corner there was an Army vehicle. The Ambassador and I — I guess it must have been by that time about 1:00 or 2:00 in the morning — went to the Embassy to look at this situation.

The Soviet Union had had a couple of cars around the Embassy, and people were trying to get into the compound, and see what they could find. And then we discovered that we didn’t lose a single piece of paper, which was quite different from what happened in Iran. I remember we walked around the Embassy a couple of times with the GSO… — the General Services Officer — and the building was still so hot you couldn’t get close to it even though there were no more flames. The bricks were almost glowing. We had no communications, obviously.

“We ran up a $12,000 telephone bill, which we sent to the Pakistani government with our compliments”

KING: The next morning we moved into the AID [U.S. Agency for International Development] building which was some blocks away. The Army was now in complete control of things.

We made a telephone call to Washington, and left the receiver off the hook for the next three days, and ran up a $12,000 telephone bill, which we sent to the Pakistani government with our compliments. That was our only communications for three days.

The decision was made in Washington, in which we could but concur, that dependents had to leave because we didn’t know what this was going to lead to. The Department commandeered the Pan Am around-the-world flight in New Delhi, threw off the passengers, and sent it to Islamabad. That happened the next morning.

During the day we got ready for the plane’s arrival. Thanksgiving dinner had been all prepared, so I said, “To hell with it. I don’t care what has to be done, I’m going home and have Thanksgiving dinner.” So we had turkey, all the things that go with it, then I went back to work.

Because of the reports that there was going to be more trouble, and a need to move quickly, we moved all dependents into four different houses in the city, where they slept on the floor that night. The plane was coming early in the morning. Then they were taken with armored personnel carriers to the Rawalpindi airport, and everybody got off with no problems.

And after that there were several scary situations, but basically we were never faced with that again. I mean, this kind of internal threat from mobs did not reoccur, although there was one bad day in which a mob of Shiites got on the loose in Islamabad, but their object was the government and not us.

It took us eight months to get dependents back, which seems like an awfully long time, because as I said, after that there was nothing further. But having spent all the money to move, you know the State Department is reluctant to send everybody back and then have it happen again. It doesn’t look very good.

We expected two or three months, but every time the bureau would propose that dependents be allowed to go back, Secretary [of State Cyrus] Vance would say no. Everybody else agreed, but invariably he would say, “No, they’re not going back.” And that’s not the kind of thing you’d think the Secretary would have strong views on. He later resigned over the attempt to rescue the [Iran] hostages, and that explains why. He knew this was coming. He didn’t agree with it, and he was not going to have us in that situation again. He was absolutely correct.

“The bill was presented to the Pakistanis, it came to $21,500,000. And the Pakistanis paid.”

HAGERTY: Another little amusing tale on all of this is that a Southerner in the GSO, Wannie Lester, who was a retired Seabee [Construction Battalion in the Navy], was very popular with the American journalists, whom he had come to know at our Club.

Several days after the attack, while he was standing outside this burned out shell, one of them said, “Well, what do you think, Wannie? How much do you think the damage cost?”

He looked again at the building and drawled, “Well, Ah don’t know. But Ah’d guess about 21 and half million dollars.”

The Ambassador was upset when he heard this, because we hadn’t begun to estimate the bill on this.

But two years later, when the bill was presented to the Pakistanis, it came to $21,500,000. And the Pakistanis paid.