“Where you stand depends on where you sit” – an oft-heard epigram used to describe negotiations. And it’s true – something as simple as a seating arrangement, with one side facing the other across a long table can only serve to encourage rigidity and a sense that the negotiations are a zero-sum game. Because of this, mediators will often get the conflicting parties in a neutral site to break the ice. That was precisely the idea behind the two-day conference of U.S., Israeli and Egyptian Foreign Ministers on July 18-19, 1978 at Leeds Castle in Kent, England.

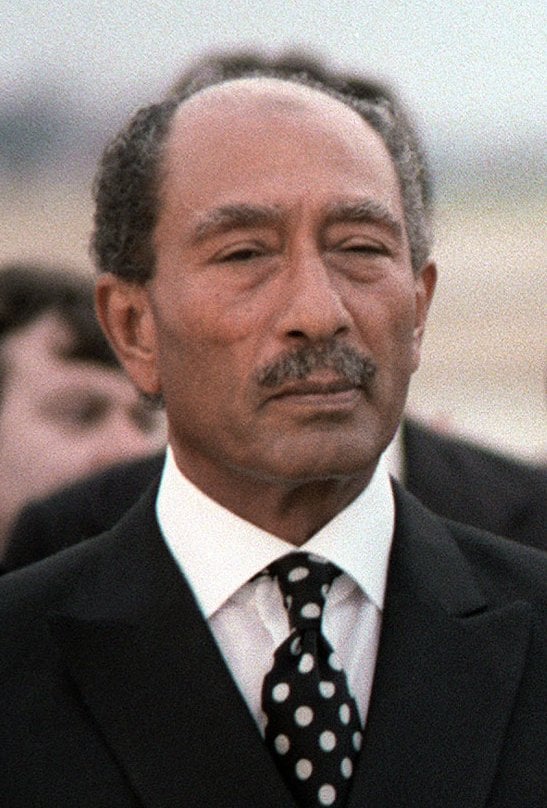

Relations between Israel and Egypt remained tense after the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Negotiations had gone on for five years and progress was frustratingly slow. Egyptian President Anwar Sadat helped break the logjam with his historic visit to Jerusalem in October 1977, while Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin countered with a 26-point plan, which would set up an interim local Palestinian government on the West Bank for five years, while Israeli troops would continue to handle defense and security matters.

These gestures encouraged the Carter Administration to take a more proactive stance on mediation, including the little known dinner at Leeds. Dr. Harold Saunders, then the Director of Intelligence and Research (INR) at the State Department, had been deeply involved in Henry Kissinger’s shuttle diplomacy and was one of the few attendees at the conference. It was at Leeds, far from the bright lights and harsh realities of the Middle East, that the parties began to listen to the other side more attentively. This eventually paved the way for the Camp David Accords, which settled the war between Egypt and Israel. Saunders was interviewed by Thomas Stern beginning November 1993.

Go here for other Moments on the Middle East and on negotiations.

“Sadat became frustrated by the slowness of our approach. He came to the conclusion that he had to break things loose.”

SAUNDERS: The first nine months of the Carter administration were devoted to trying to draw some terms of reference for another Middle East conference, substantive objectives and an organizational structure for comprehensive peace negotiations. All these efforts raised major issues.

Towards the end of this period, [Egyptian President Anwar] Sadat became frustrated by the slowness of our approach and its extreme legalistic framework. He came to the conclusion that he had to break things loose. Hence his visit to Jerusalem, which was essentially his idea — we were not party to that decision. I think it is fair to say that if we hadn’t pressed for a Geneva conference, Sadat may never have gone. We used his trip to Jerusalem as a springboard to push all parties to go to Geneva.

Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem was followed by a series of conversations among the three countries — Egypt, Israel and the U.S. — which went on into early 1978. [Assistant Secretary of State for Near East Affairs and later Ambassador to Egypt] Roy Atherton was asked to concentrate on the Middle East process in an effort to establish a set of principles that Egypt and Israel might agree on. It was hoped that Roy’s efforts could lead either to a resumption of the Geneva conference, [the international attempt to negotiation a solution to the Arab-Israeli conflict] or at least to an Israel-Egypt agreement of some kind.

So Roy began to spend a lot of time in the area itself and [Secretary of State Cyrus] Vance decided that that was the best use of Roy’s talents at that time. He therefore appointed Roy as a full-time negotiator, with the title of Ambassador-at-Large, and asked me to take over Roy’s position as Assistant Secretary.…

In the Spring of 1978, Roy Atherton was in the Middle East trying to use Sadat’s initiative to formulate a set of principles that would move all the parties toward Geneva. In fact, because of the situation on the ground, we began to focus on an Egyptian-Israeli peace process rather than an area-wide comprehensive process. By July 1978, it appeared that the Sadat initiative might come to naught.

In the face of that prospect, Vance chaired a meeting of Egyptian and Israeli officials at Leeds Castle at the end of July. It was a very good meeting, although it has never received much public attention. We didn’t have any concrete objectives in mind; we were merely trying to take stock.

“Leeds was an opportunity for both the Israelis and the Egyptians to wonder ‘what if’”

We did have the Atherton principles [based on U.N. Security Council Resolution 242, adopted after the 1967 war, which calls for withdrawal from occupied territories; the Egyptians had said that meant all territories and the Israelis disagreed], which appeared to have general acceptance, but were not motivating the parties to make further progress. Our objectives for the Leeds Castle meeting was essentially for the Egyptian and Israeli officials to become acquainted so that they could see each other as human beings and not as intransigent representatives of intransigent governments.

The Castle was surrounded by a moat. That was both a fact and a symbol.

We were originally going to meet at the Churchill Hotel in London, but just before the meeting was to begin, a Palestinian had been shot near the hotel. So the British, for security reasons, refused to let us use the hotel and put us in the Castle where they could better protect the delegates.…

Originally, we had planned to have the Egyptian and Israeli delegations eat in separate dining rooms; we would spread ourselves among the other two. But then Mrs. Vance suggested that that was not really appropriate and that a greater mixture was really in order. We all ate in one dining room and that was very helpful in breaking down barriers.

We all sat at a long table and we would sit in different places at every meal. It turned out to be no big deal and worked very well. The Vances are so gracious and charming that they set the tone. I don’t think they saw anything insidious or devious about it. In fact, especially since Sadat’s trip, they saw it as perfectly normal that people attending the same conference would share their meals together. I think both the Egyptians and the Israeli were in fact ready for this greater congenially.

It was a very good meeting, with very substantive discussions. No one went there for the purpose of achieving an end result. We went to Leeds to take stock. The discussions were wide ranging.

I remember someone asking [Moshe Dayan, once a military leader and then the Israeli Minister of Foreign Affairs] what the Israelis really wanted from a final West Bank settlement. He said that all the Israelis wanted was access to the Holy sites.

Then we got to the question of whether an Israeli should be allowed to purchase a house in Hebron. Dayan said that if he could buy a house in West Virginia, then he should be able to buy one in Hebron. I have never figured out why he chose West Virginia; it was almost bizarre. Of course, that exchange led to the next question which was whether a Palestinian could buy a house or lease a condominium in Haifa. That is an illustration of the wide ranging discussions that took place.

Leeds was an opportunity for both the Israelis and the Egyptians to wonder “what if.” It gave them a chance to talk about problems without being under pressure to reach any settlement. The Leeds Castle meeting agreed that the Foreign Ministers should meet at the American surveillance site in the Sinai passages.

It occurred to me at the time that if such a meeting were to be held, it had to conclude with some significant agreements. Using Roy’s principles and the Leeds discussions as a guide, I sat down, when we returned to London, to draft a tentative agreement that the Foreign Ministers could sign. That draft, after many reiterations, actually became the first draft of the Camp David Accords.

But even at Leeds Castle, we were not thinking of a heads-of-state meeting; we were much more modest. But in August, it was President Carter who suggested that his Israeli and Egyptian counterparts be invited to Camp David.

“Both sides began to see that the other was not always necessarily threatening”

I have often said, when asked to discuss the Camp David negotiations, you can’t talk about that single event without talking about the four-year peace process that preceded it.

I certainly believe that personal relationships developed further during the Leeds Castle, although some from both sides had met before in more formal settings. Those relationships contributed to the capacity of people to think together and to talk together in imaginative and constructive ways.

You would probably not have had a Camp David success had there not been earlier dialogues. Kissinger always made it a point, at the start of every meeting during the shuttles, to describe for his interlocutors what the views, personalities and the interests of each member of the other side’s negotiating team were.

When people ask me what the shuttles accomplished, I always mention that each side began to know their counterparts on the other side without having ever met them. Sadat could make a proposal and — based on his briefings from Kissinger — would know that Dayan might find it hard to accept, but another member of the Israeli team might well like it. That was true for the Israelis also.

Of course, the Egyptian and Israeli teams met when Sadat went to Jerusalem and thereafter met occasionally. That led to Leeds Castle and beyond that, to Camp David. By the time they met at Camp David, the Israelis and the Egyptians were sufficiently accustomed to each other that it was not novel for them to work together.

I believe that it is a very important part of any negotiations to know the person on the other side of the table. It goes far beyond just knowing the potential reactions to a specific proposal. When people don’t know each other, they tend to dehumanize the “enemy” and almost demonize him.

The first positive benefit of the ever increasing personal contacts was that people came to respect each other. They didn’t have to like the other. They didn’t have to agree with the other, but each Israeli and Egyptian began to see that their counterparts were serious individuals, with ability, and with some valid point of view — at least valid within a given frame of mind.

Furthermore both sides began to see that the other was not always necessarily threatening. I believe it was that humanization process which permitted the two sides to recognize that each had certain needs and interests they would have to meet if there were to be any kind of peaceful relationship established. Once that basic premise was accepted, it permitted both sides to approach problems that affected both.

These were problems that could only be solved by both sides working together. That required accommodations by both sides. The process became easier as both sides agreed that they needed to have a peaceful relationship. In order to get to that level of acceptance, both sides had to see each other as humans with valid needs and claims. They each had to feel what the other was saying; they, not anyone else, had to be expected to see the world through someone else’s eyes.

You have to feel that the other person has a legitimate point of view that demands some positive response from you even if you don’t agree with it. You have somehow to feel the intensity which underlies that other point of view and respect the sincere spirit in which it is offered. You have to accept that a view is so real that you have to come to terms with it, if you are to make any progress on your agenda.

You don’t have to accept the other point of view as correct, but you do have to acknowledge that the other person posits those claims and needs as strongly as I postulate my own. It cannot be dismissed as just rhetoric — an Israeli phrase used to characterize some of Nasser’s speeches. It cannot be ignored, but must be dealt with.

“Carter’s initiative — Camp David — was a recognition of Sadat’s initiative — Jerusalem”

After we came back from Leeds Castle, Carter sent Roy, Bill and me to the Middle East with the invitations to the Camp David meeting. Then we started the preparations for Camp David using the draft paper prepared at Leeds Castle.…(Photo: Getty Images)

[The Leeds Castle] conference gave rise to the idea of a Foreign Ministers’ meeting to take place within the next two or three months. Carter took that idea and turned it into a meeting of Chiefs of State at Camp David….

The centerpiece of this new strategy was Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem, but there were other signs as well. Those indicators gave rise to a Carter sense of obligation to Sadat, who had taken an extraordinary and very courageous step.

I think that Carter suggested Camp David because he felt that he owed Sadat some public recognition; his initiative — Camp David — was a recognition of Sadat’s initiative — Jerusalem.