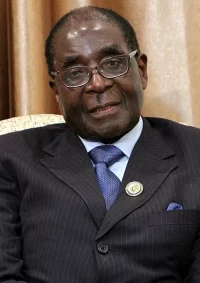

Robert Mugabe is one of the more controversial figures in Africa. He rose to prominence in the 1960s as the leader of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) during the conflict against the conservative white-minority government during the Rhodesian Bush War (also known as the Zimbabwe War of Liberation) and was a political prisoner in Rhodesia for more than 10 years between 1964 and 1974. He joined forces with Joshua Nkomo in the “Patriotic Front” at the end of the war to sign the Lancaster House Peace Treaty with the British government.

The Treaty mandated a ceasefire and elections, putting an end to the conflict responsible for more than 12,000 deaths. Mugabe won the British-supervised elections over Nkomo and became Prime Minister on April 18, 1980, when Zimbabwe became independent. He then became President of Zimbabwe in 1987 when the position of prime minister was abolished, making him the only head of state the country has ever known in its 34 years of sovereignty.

Herman Cohen’s The Mind of the African Strongman, part of ADST’s Diplomats and Diplomacy series, elaborates on Mugabe’s rise to power, his hand in the Mozambique Civil War, and tragic decline as an international pariah. Cohen closes with a brief discussion of a post-Robert Mugabe Zimbabwe. The book offers a unique first-hand account of working to implement U.S. foreign policy in Africa, a largely misunderstood region plagued with complex issues, and is therefore highly anticipated in the academic, policy, and diplomacy worlds.

Go here to read Zimbabwe, Death of a Nation. You can read about Ivory Coast’s Félix Houphouët-Boigny here and other Moments on Africa.

Mugabe’s Rise in Politics

COHEN: Beginning in 1957 with Ghana, the British started granting independence to its African colonies. In 1964, Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland gained independence as Zambia and Malawi, respectively. These developments in Southern Rhodesia’s immediate neighborhood stirred up both white and black citizens. The whites felt that their country was far more advanced economically than the newly independent states and demanded equal treatment. The blacks demanded that the United Kingdom refuse independence until majority rule under democracy could be negotiated.

These two opposing views of independence had a profound impact on Rhodesian politics. The white community became more radicalized and extremist, as passions for independence intensified. Within the black community, passions for equal rights and majority rule gave rise to a strong political movement that the whites saw as subversive and dangerous.

Within this heated political context, Robert Mugabe became a leading advocate for equal rights and majority rule. A university graduate with a degree in education, Mugabe was completing his graduate studies in Ghana in 1960 shortly after that British colony achieved independence in 1957. Mugabe came under the influence of Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, a leader of significant charisma. Nkrumah’s message was, “Marxism and African unity.” From that moment, Mugabe started down the road toward full acceptance of Marxist ideology as interpreted by Lenin.

When Mugabe returned to Rhodesia in 1961, he found a full- fledged black nationalist movement in an expansion mode under a popular and charismatic leader, Joshua Nkomo. Mugabe’s message had an ideological element that appealed to educated blacks looking for an alternative to Nkomo, who lacked intellectual weight. In addition, Nkomo came from the minority Ndebele ethnic group. Mugabe was part of the majority Shona group. The result was two competing nationalist movements that weakened the overall quest for majority rule.

When I arrived in Rhodesia in late 1963 on assignment to the American consulate general, Mugabe was in jail serving a ten-year sentence for subversion. My job was to meet with black political leaders. While I was able to see Nkomo, president of the Zimbabwe African Peoples Union (ZAPU), I was not allowed to see Mugabe in prison. Nkomo’s message was, “When will the United States give us our majority rule?”

In other words, you can put pressure on the United Kingdom, the colonial power. Mugabe’s followers, in his Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), talked to me about the inevitable revolution. Hatred between the two organizations was strong. In 1965, the white minority regime unilaterally declared independence for Rhodesia in defiance of the UK colonial power, which imposed full economic sanctions, including an oil blockade. This set the stage for an inevitable armed conflict.

In 1977, Mugabe was authorized to attend a conference in Zambia. Instead of returning, he slipped into independent Mozambique, where he started an armed insurgency against the illegal white regime. Nkomo and his party joined the insurgency from a separate base in Zambia. The only country willing to allow Rhodesian trade to transit its territory was apartheid South Africa. The war lasted three years. During that period, the ZANU operation was the more successful in penetrating deep into the Rhodesian countryside, causing great havoc among the white commercial farmers. Working from across the Zambezi River in Zambia, the ZAPU insurgency was relatively feeble. Hence, the black population of Rhodesia saw ZANU in action far more often than ZAPU.

Peace and the Birth of a Nation

It was September 1988. The United Nations General Assembly General Debate was in full swing. As I walked through the hall of the General Assembly building with Secretary of State George Shultz, I said, “I ran into Robert Mugabe, President of Zimbabwe, a few hours ago. He wants to see you.”

Shultz’s face reddened. “Absolutely not. Keep him away from me. He is constantly lecturing about issues that should not concern him. He wants us to stop helping the anti-Soviet rebels in Afghanistan. He is a nonaligned nag.”

Flash forward to January 1991. “Desert Storm,” the first Gulf War, was still ongoing. Zimbabwe had just joined the UN Security Council as a non-permanent member for a two-year rotational tour.

President George H. W. Bush was sensitive to Security Council voting about the war. During August 1990, Secretary of State James Baker instructed me to make sure that the three African members of the Security Council voted in favor of going to war against Iraq. I succeeded in persuading Zaire, Ethiopia, and Côte d’Ivoire to vote with the United States for the crucial war resolution in August.

With Zimbabwe replacing Côte d’Ivoire in January 1991, we were concerned that President Mugabe, a good friend and collaborator of Iraq’s president Saddam Hussein in the Non-Aligned Movement, would demonstrate hostility to the international military action to liberate Kuwait from Iraqi occupation. I decided to visit Mugabe, whom I had known since he became Zimbabwe’s first president in 1980. Making flight reservations, I was informed by State Department security that I could not travel through the usual European route.

Saddam had unleashed many terrorist friends to attack American interests in Europe, Africa, and beyond. My only option was to fly to Brazil, and then across the south Atlantic to Johannesburg, South Africa, and then north to Harare, the capital of Zimbabwe. Accompanied by my executive assistant, Karl Hoffman, I arrived at Mugabe’s office with some trepidation. In view of his Non-Aligned leadership, I expected to be thoroughly harangued. I made my pitch and waited for Mugabe’s hammer.

He thought for a while and then made a response that blew me away: “Secretary Cohen, I don’t approve of strong powers invading and occupying weaker powers. Iraq must be forced out of Kuwait. Tell President Bush that I am fully on his side on this question.” Wow! That was an unexpected surprise. Walking out of Mugabe’s presidential office complex, I said to Karl Hoffman, “That was too good to be true. Let’s take tomorrow off and visit Victoria Falls.”

Mugabe was true to his word. Shortly after our visit, Iraqi agents slipped into Zimbabwe and set up in a hotel with a direct line of sight to the American Embassy. They were preparing to kill the US ambassador. Zimbabwe intelligence spotted them upon arrival, followed and surveilled them, and then arrested them. The Zimbabwe service sent them to Cyprus to American counterparts for interrogation.

American diplomats generally found Mugabe a reasonable interlocutor between 1980, when he became president, and the year 2000, when his internal policies became totally radical and Zimbabwe started a steady descent into economic and political chaos. British diplomats presiding over majority rule and independence negotiations in 1979 found Mugabe to be moderate and pragmatic. American diplomats who observed those talks said the same thing.

Like South Africa, Zimbabwe was under white minority rule for over half a century. While South Africa achieved full independence from Great Britain in 1912, Zimbabwe remained a British crown colony as Southern Rhodesia between 1928 and 1980. The colony had been granted self-rule in 1928. This allowed the white minority to keep the black majority totally subjugated, since the Africans had no voting rights. The Rhodesian system of segregation was a bit less harsh than the South African apartheid system, but the blacks felt totally repressed nevertheless….

Marxist-Leninist Zimbabwe Thrives

Under the influence of Nkrumah of Ghana and his lengthy reading of Marxist literature during his ten years in prison, Mugabe took over the political leadership of Zimbabwe as a confirmed Marxist-Leninist. That meant, above all, that the vanguard peoples’ party would guide the nation to full socialism. ZANU, therefore, would remain supreme and permanently in power. As a result, Zimbabwe’s laws were written and amended so that ZANU would become the only legal political party.

During the 1990s, visitors to Harare, Zimbabwe’s capital, saw that the real political and governmental action took place not in the halls of the bureaucracy but at ZANU headquarters, standing on its own plaza in the heart of downtown. All major policy decisions were made there by the party’s political bureau. Between 1980 and 2000, Zimbabwe was an economic and political leader in Africa. High agricultural production was a big money earner. Its Virginia tobacco exports were second only to the United States. Zimbabwe maize was exported to most southern African countries.

One of my most important discussions with Mugabe in the early 1990s concerned the civil war in Mozambique. During that country’s guerrilla war of 1976–1979, the Rhodesians had financed and armed a guerrilla force against the independent African regime in Mozambique. This was done in retaliation for the Mozambican support to Mugabe and his fighters. After the beginning of peace in Zimbabwe, the Mozambique guerilla war continued. After Mugabe became the political leader in Zimbabwe, the white apartheid regime in South Africa took over support of the anti-regime guerrillas in Mozambique, known as RENAMO [Mozambican National Resistance]. In the State Department, we felt that the Mozambique war was ripe for mediation toward a democratic transition.

We embarked on a number of initiatives that led to progress. But the most difficult problem was to persuade the RENAMO leader, Alphonse Dhlakama, to accept the prospect of laying down his weapons and participating in a democratic process. His paranoia was great, and he fully expected to be killed by the Mozambique military if he entered political life. I had a number of secret meetings with Dhlakama in Malawi, but I was never able to fully persuade him to accept negotiations and subsequent entry into political life.

The person who accomplished this was Robert Mugabe. I asked Mugabe to undertake this task because he and Dhlakama came from the same Shona ethnic group that straddles the Zimbabwe-Mozambique border. Mugabe succeeded where many of us failed, and in May 1992 in Rome, he presided over the signing of the Mozambique peace accords. As of early 2013, Dhlakama continued to be active in Mozambique politics as an opposition leader.

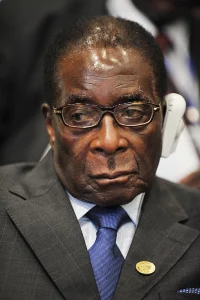

From Cooperative to Destructive: the Decline of Mugabe’s Popularity

I started to suspect something was going wrong when I sat about five feet away from Mugabe at the annual summit meeting of the Global Coalition for Africa [GCA] in November 1995, in the conference center in Maastricht, Netherlands. I was a senior advisor to the GCA, an intergovernmental forum designed to bring donor countries and African countries to a consensus on the correct economic policies to promote development. In his plenary address, Mugabe made an impassioned plea for the international community to prevent African countries from abandoning democracy. It was a period when most African countries were experimenting with multiparty democracy after several decades of one-party authoritarian rule.

By the time of the conference, some of the African countries were beginning to slip backwards from their democracy toward a return to authoritarianism. Mugabe’s plea for the sustainability of democracy was elegant and heartwarming. But after he completed his oration, he continued on with another, totally irrelevant, subject that made us all gasp. He started a rant against homosexuality that he considered a total abomination. The sentence that has stayed in my memory ever since was: “How is it possible for us to allow a man to make another man into a woman?” Fortunately, Chairman Jan Pronk, then labor minister of the Netherlands, gaveled Mugabe to a close with “I am sorry Mr. President, but your time is up.”

We all looked astonished. Needless to say, word of Mugabe’s rant leaked out to the public. The gay community quickly organized an anti-Mugabe demonstration. During the second half of the 1990s, Mugabe’s popularity started to decline. His government had done an excellent job of providing basic education to the youth.

But his Marxist ideology caused him to be suspicious of the private sector, thereby discouraging new private investment. The result was a huge influx of high school and university graduates into the labor market, with very few jobs available. When I visited Harare in 1998, ordinary people working in hotels, stores, and restaurants were quite open in expressing their fatigue with Mugabe.

Mugabe tried to restore his popularity through the expropriation of commercial farmland owned by white farmers. He first demanded that the United Kingdom finance the purchase of land for the benefit of African farmers, as they had done shortly after Zimbabwe’s independence under black majority rule. The UK government refused to start a new program of land purchases, claiming that the earlier program had benefited political elites and not the landless rural peasants.

In a desperate effort to stimulate a feeling of nationalism, Mugabe unleashed his ZANU party thugs onto white-owned farmland, resulting in severe hardship to the white farmers and great damage to the Zimbabwe economy. A once great exporter of maize and Virginia tobacco went into deep decline.

Mugabe, one of the most important African freedom fighters, was becoming an international pariah. Mugabe’s rallying cry was, “Our lands were illegally stolen by the whites one hundred years ago.” The truth of the matter was that the majority of white-owned farms had been purchased after he had been elected prime minister in 1980. The expatriate farmers had confidence in Mugabe’s moderation and respect for property.

After all, he had appointed a white Zimbabwean minister of agriculture. My last private conversation with Mugabe took place in the year 2000 in the midst of the farm confiscations. He had asked me to advise him about what he could do to reverse the economic decline. He did not want to get into the farm issue. I told him I would develop an economic stabilization plan for him and suggested that he try to link up with the World Bank and the IMF for financial assistance based on needed policy reforms.

During that conversation, he was perfectly rational and showed no sign of hysteria about what was going on around him in the countryside. Some say that the loss of his first wife, Sally, and his second marriage to Grace Marufu were important factors in his change of outlook. His first wife, a Ghanaian, was deeply interested in social development. His second wife was apparently interested mostly in the accumulation of wealth.

My own view is that Mugabe was driven mainly by his deep adherence to Marxism-Leninism. This doctrine taught him that the vanguard party, the ZANU-PF party in his case, must never give up power. In the late 1990s, it was clear that his party would eventually lose out in free and fair elections. He had to do everything possible to forestall the loss of power. Hence, he resorted to the farm confiscations, electoral intimidations, and sheer brutality in the tradition of Lenin and Stalin.

Many years later, I talked to some of my retired colleagues who had known Mugabe in the early 1960s, when he was an aspiring political leader. They told me that his only interest was political power. He expressed no interest in economic development, land ownership, or any bread and butter issues.

He cared only for power, as a devoted Leninist would. As of the beginning of 2014, Zimbabwe was still in the throes of disaster, as the Mugabe regime continued to flounder in corruption and repression. Mugabe, in his upper eighties, appeared to be under the control of military and high political cronies. Zimbabwe awaited his departure with impatience.

From an Africa-wide perspective, Zimbabwe presents an extreme example of the one-party state that acts as a drag on economic development, among other reasons. The party-state is full of careerists who have few expectations for employment opportunities in the private sector. Thus, apart from Leninist theories about the “vanguard party,” keeping the party in power is the highest political priority.

One ameliorating phenomenon is the constitutional two- term mandate for some heads of state, as in Tanzania, Zambia, and Mali. While the party remains in power, the required turnover of heads of state every eight years sets up a competitive dynamic within the party that has some democratic aspects.

As Zimbabwe’s economy has plunged since the year 2000 and as Mugabe’s heirs see themselves inheriting less and less, maneuvering for power within the ZANU party has become more intense. Tragedies such as the one perpetrated by Mugabe and his ZANU party also have an impact on the surrounding region. Zimbabwe used to be a regional breadbasket, especially for maize, the staple food of most southern African populations. The decline of maize production in Zimbabwe has caused the price of this staple to rise in the Congo, Zambia, Mozambique, and Angola.

One irony that must be gnawing on Mugabe is the way neighboring countries have welcomed Zimbabwe’s white farmers with open arms. Those who are still willing to give Africa a second chance are doing well as commercial farmers in Zambia, Mozambique, and even in some places in Nigeria; while back in Zimbabwe, most of the former commercial farms are now home to African peasant farmers who cannot get title to the land because of Mugabe’s Marxist policies. Without land titles, they cannot obtain bank credit and are thus condemned to remain subsistence farmers.

As of early 2015, Zimbabwe was still in the throes of disaster, as the Mugabe regime continued to flounder in corruption and repression. Mugabe, at age 90, seemed still to be under the control of military and high political cronies. But in October 2014, Mugabe’s wife Grace suddenly entered politics as chairperson of the ZANU Women’s League. From this position, Grace began to make statements that she expected to succeed to the presidency after her husband’s demise. This added to the impatience of the Zimbabwe people to see the end of the Mugabe. Any effort to make Grace the ZANU-PF candidate for president will unite all factions against her.

A Post-Mugabe Zimbabwe?

In my view, with or without Mugabe, ZANU-PF will break up into competing factions. It will be military against civilians and a free-for-all among different groups within the party, each one following a different senior leader considered the legitimate heir apparent. A military takeover would not be surprising. The medium-term prognosis for Zimbabwe as of early 2015 was bleak. Mugabe may be Africa’s last true-believing Marxist-Leninist.