The United States found itself embroiled in several interventions in the 1990s that focused on upholding basic human rights standards and encouraging democratic regimes to flourish, from Somalia to the Balkans to America’s own backyard in the Caribbean. Despite Haiti being the second nation in the Western Hemisphere to proclaim independence, it has suffered from the beginning to establish an orderly and legitimate system of governance.

In 1991, anarchy ensued once again when the Haitian military, led by Commander-in-chief Raoul Cedras, overthrew Jean-Baptiste Aristide, a controversial yet nevertheless democratically elected President of the nation. The coup represented a decisive step backward from the overall positive trend towards democratization in the region and led many in the U.S. to call for an intervention to restore human rights and democracy.

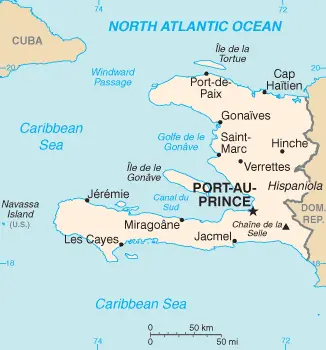

In October 1993, the Clinton administration dispatched the USS Harlan County to prepare for the return of Aristide, but it was met at the pier in Port-au-Prince by a mob of Haitians, appearing to threaten violence.

With the street battle in Mogadishu only a week past, the administration proved unwilling to risk casualties in Port-au-Prince. The ship pulled away.

Four days later, the United Nations Security Council imposed a naval blockade on Haiti. Over the next several months the administration prepared for a full-scale invasion while pressuring the coup leaders to step down. After intense diplomatic maneuvering, in July 1994 Washington was able to secure United Nations Security Council Resolution 940 authorizing the removal of the Haitian military regime, the first resolution authorizing the use of force to restore democracy for a member nation. As the U.S. prepared for the invasion, scheduled for September 19, the Haitian leadership capitulated in time to avoid bloodshed. Aristide returned to Haiti on October 15.

Sarah Horsey-Barr, the Deputy Chief of Mission to the Organization of American States (OAS), and Harriet C. Babbitt, the U.S. Ambassador to the OAS, discussed how OAS members felt about yet another American intervention in the region. Likewise, James Dobbins, who served as the State Department’s Deputy Special Advisor to Haiti, recounts the hands-on experience he had in both planning and implementing the operation. Each of these individuals was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy in August 2000, November 2002, and July 2003, respectively.

Read about the disagreements many at Embassy Port-au-Prince had with U.S. policy in the late 1990s. Go here to learn about Baby Doc Duvalier’s move into exile. Learn about the U.S. intervention in Panama.

“The world and this hemisphere were tired of Haiti”

Sarah Horsey-Barr, Deputy Chief of Mission, OAS, Washington, D.C., 1992-1995

HORSEY-BARR: There was a coup in 1991 in Haiti. The wave of boat people – exodus of refugees by boats, which most often are not boats at all but rafts of some sort, from Haiti seeking haven in the United States – shot up dramatically, and that’s why it was a campaign issue, that’s why it was one of the first, if not the first, foreign policy issue that [President Bill] Clinton had to deal with.

The OAS had passed the year before at the highest level of the Foreign Ministry a resolution talking about democracy being an indispensable part of membership in the OAS, which is nothing new from the charter but it took it several steps further setting a new direction to democracy with grounds for hemispheric action.

So this came on the heels of that. The OAS decided to start ratcheting up actions against Haiti in the hopes of reversing and getting the coup guys out quickly. That did work, and so what we saw over the next two or three years, via constant pressure from the United States because of the domestic implication, was a continual ratcheting up of the screws, tightening the isolation of the leadership in Haiti, and that culminated in 1993 with the imposition of an embargo.

I think the world and this hemisphere were tired of Haiti, and I think the Haiti fatigue attenuated everybody’s interests. So on the part of the Latins, they viewed the American invasion as “All right, fine, that’s great; they went in and they removed an eyesore, and that’s terrific.”

On the Caribbean side, the Haiti situation affected the Caribbean states much more directly than it affected the Latins just because of proximity. What is not talked about is how many refugees they got and what it did to their economic situation, the other Caribbean countries that were close to Haiti, and what the embargo did to them. So I think there was a bit of happiness that we had done it for them.

“They couldn’t imagine wasting time on this country with its illiterate black people”

Harriet C. Babbitt, U.S. Ambassador to the OAS, Washington, D.C., 1993-1997

BABBITT: Oh, the problems with Haiti. They are still going on. Aristide was elected, but living in a little apartment in Georgetown. The United States’ position was that, although he would not have been our choice, he was the people’s choice. Therefore, we were going to get Aristide back. That was the right thing to do.

Many countries in the hemisphere were completely indifferent to Haiti. Many Latin American countries were not officially racists, but were unofficially in every way.

They couldn’t imagine wasting time on this country with its illiterate black people. It was hard to get the level of interest in Haiti that we wanted.

The Caribbeans cared about Haiti because it was in their neighborhood. One of the things that we wanted, and Deputy Secretary Strobe Talbott was responsible for, was a UN approval….The Argentines gave us a boat or something. Somebody else gave us something else, so that it would be a multilateral endeavor, but essentially it was U.S. military. We were negotiating with the Turks and Caicos, and almost everybody else, for taking Haitian refugees. So, there were many parts to this. But the political OAS task was to pass a resolution expressing to the UN the desire for the United States to invade.

We said that if the government of Haiti requested an invasion, then it was no longer an affront to their sovereignty. We crafted some language for Aristide to give in his speech at the OAS general assembly, which would, in effect, request an invasion.

But nevertheless, Aristide was the constitutionally elected president of Haiti. That satisfied the Mexicans need from a legal basis, because the constitutionally elected president has requested it. They didn’t care very much about Haiti anyway.

“This was a country that the United States had largely ignored for 200 years”

James Dobbins, Deputy Special Advisor to Haiti, Washington, D.C., 1994-1996

DOBBINS: Prior to my appointment, there had been a coup, President Aristide fled the country, and he’d continued to be recognized. The U.S. and the rest of the OAS and international community continued to accord him legitimacy. He eventually located in Washington as part of a government in exile. Nobody recognized what we called the de facto regime. Political and eventually economic sanctions had been applied by the United Nations. Most of that had occurred before the Clinton administration came into office.

There had been an effort to negotiate an arrangement by which Aristide would return, but there would be safeguards for the factions that had ejected him, his powers would be somewhat limited, and an international peacekeeping force, which would consist of essentially trainers rather than a more robust force, would come in to begin trying to professionalize the Haitian army, which had staged a coup.

That effort foundered just three or four days after the Blackhawk down incident.

The ship [the USS Harlan, pictured] that contained these UN-mandated military trainers, or at least the American component – they weren’t to be all Americans, but several hundred of them were to be Americans – pulled into the harbor in Port-au-Prince and a small unruly crowd that had been generated by one of the local, sort of extreme party leaders, who turned out to be a CIA agent, it was later learned, turned out a sort of small, unruly crowd on the pier.

And the Clinton administration, terrified of yet another incident, actually turned the ship around and sailed out of the harbor, despite the fact that our deputy chief of mission, a slight woman [Vicky Huddleston], was standing on the pier, waiting for them to come ashore and was herself braving this hostile crowd without any support. These 700 U.S. soldiers sailed around and left, and this sort of retreat under fire was another extreme humiliation.

Shortly thereafter, Randall Robinson who was a black writer, leader, activist here in Washington, went on a hunger strike, saying he wasn’t going to eat unless the administration changed its policy on returning Haitians asylum seekers without examining their claims to asylum, simply returning them to Haiti, making of course the comparison to the Cuban thing. He continued and got a good deal of publicity for this, for a couple of weeks, and it eventually became the catalyst that led Clinton to change the policy….

The policy changed in two respects. One was the statement that implied that if we were not able to resolve the impasse over Haiti’s political future diplomatically in a way that led to the return of Aristide, we were prepared to use force in that regard.

The second was that we would not return Haitians, boat people, in effect, people who were intercepted at sea, we would not return them to Haiti until we had at least examined their claim for asylum. So that was the policy, the announcement that was more or less coincident with my appointment, and those were the policies that I was supposed to coordinate the implementation of….

The intelligence community had apparently briefed the Congress that Aristide was not only mentally unbalanced, but also dependent on drugs, was a drug abuser as well as mentally unstable. To some degree in retrospect, their cautions on Aristide have proved justified, but some of the other cautions about his attitudes and likely behavior in power were better substantiated.

In any case, there was a pretty big gulf in the administration between those who thought he had been democratically elected, had shown poor judgment, but basically had the right instincts and with the right amount of guidance and support could be channeled constructively and those who felt that he was incorrigible.

I don’t know that the Pentagon had a view on Aristide. They simply didn’t want to get engaged on this and were strongly resistant until a couple of months before the intervention. Then they did come around, but for the first few months of these debates, they were strongly opposed to any use of force, or even any involvement in the peacekeeping activity. So that was an uphill battle. (AP Photo/Ron Edmonds)

There were a lot of debates within the administration, and the knowledge was somewhat limited simply by the fact that this was a country that the United States had largely ignored for 200 years.

It had been the [George H.W.] Bush administration which had imposed economic sanctions and secured OAS and UN resolutions calling for Aristide’s return. I think that there was a feeling that there was an issue of principle here of some consequence.

By this time, you had achieved democratic transitions in every country in Latin America except Cuba. Every president in Latin America, except Fidel Castro, had been freely elected, and so this was a reversal in a trend that was regarded as very positive, and there was bipartisan support for the concept that one should be willing to make an effort to preserve a democratic hemisphere.

So, the policy announcement that preceded me was a presidential determination that he was prepared to threaten the use of force, if necessary, to secure restoration of democracy. There was always a considerable uncertainty as to under what conditions he might actually authorize it.

It was clearly going to be very unpopular domestically here. It might be unpopular internationally. It might be resisted in Haiti, some people thought, and therefore we were never quite certain how sure we could be of this ultimately becoming possible until, in the end, the president did agree to do it.

But there was an assumption that ultimately an intervention was probably going to be necessary, and there were those of us who thought that the sooner the better, that the human rights situation and the humanitarian situation in the country were continuing to deteriorate, in large measure, because of the sanctions that we had applied, and that for humanitarian, if no other reasons, doing this sooner rather than later made sense.

Additionally, the refugee policy we put in place was not sustainable over an extended period of time. We simply couldn’t warehouse another 30 or 40,000 Haitians every week. There was nowhere to put them, so that was another form of pressure.

So there was planning, and there was planning on an international basis. The UN had already authorized a peacekeeping force for Haiti, and the original thought was that we would beef up that force. Using its name obviously required further UN authorization, but within the framework of the existing authorizations, use that peacekeeping force.

We went up and met with [UN Secretary General Boutros] Boutros Ghali, and his staff’s view was, “You’re not talking about a peacekeeping operation, you’re talking about an invasion. A UN blue-helmeted peacekeeping force is not suitable for that. What you need to do is get a UN Security Council authorization inviting you to invade, and then you can turn it over to this UN peacekeeping force at a subsequent phase, when you’ve established security.”

We were initially somewhat skeptical that we could get a Security Council authorization of that sort, given all the traditional resistance to interference in domestic affairs, particularly within Latin America. But in the end, we did succeed.

The Secretary General assisted in that effort and the fact that Aristide could make a formal request to the Security Council, which he ultimately was persuaded to do, also in the end gave us what was called an all necessary means resolution, which authorized the intervention.

Haiti had long been misgoverned and was continuing to be misgoverned by a combination of the army and the mulatto elites that had traditionally run the country. The coup regime wasn’t very competent and it didn’t have much legitimacy, even within the country. There was resistance, not violent resistance, but political resistance on the part of Aristide and his supporters, and Aristide had wide support in the population as a whole, and as a result there was continuous violence that was creating casualties.

There were some really clearly targeted assassinations of prominent Aristide supporters. Other of the violence was less clearly targeted as opposed to sort of more indiscriminate efforts by the security establishment to maintain control in a society in which they lacked legitimacy and support in the population.

“You won’t know until you step off the helicopter whether you’re going to have to shoot your way into town”

Well, there were plans. Once we determined that this was going to be a U.S.-led coalition rather than a UN force, the Defense Department wanted a clear answer from the State Department as to whether this was going to be an opposed landing or not, whether they needed to anticipate that there would be resistance, or whether in the end their entry would be brokered.

The State Department’s answer was, “You won’t know until you get there.

You won’t know until you step off the helicopter whether you’re going to have to shoot your way into town, or whether there’s going to be somebody there inviting you to lunch.”

They said, “Well, we can’t do that. You need to tell us one or the other, because if we anticipate resistance, then we’re going to shoot whoever comes to invite us to lunch.”

I said, “Fine, but then you’re going to drive into town shooting bank guards and crossing guards, because there’s no way we can tell you.” As events indicated, ultimately an arrangement was made only after the 82nd Airborne got on the airplane and was halfway there that we got a brokered agreement, which allowed a peaceful entry.

What the Pentagon eventually did was accede to this logic, however reluctantly, and they had two plans with two different forces. They sent down two different divisions, one that was going to force its way in, the other of which was going to go in voluntarily, and they had two plans, Plan A and Plan B, one of which involved shooting everybody as you arrived, and the other of which involved arriving and going to lunch. In the end, they were able to put into effect the second of those plans and it worked reasonably well.

There was a growing recognition that it was going to have to be an invasion. There was always some uncertainty because the President was, and remained throughout his term of office, reluctant to do these things unless he felt he really had to.

But it mounted pretty steadily in that direction, and as the prerequisites fell into place, we got a Security Council resolution that authorized it. We got a coalition that was sufficiently broad to legitimize it.

The Pentagon had a plan that it was capable of executing and the regime there remained obdurate, and Aristide was being reasonably compliant and playing his role, and, eventually the pieces came together and the President authorized the use of force.

Aristide was very concerned, because he felt they might bargain away his prerogatives, and he was quite paranoid about it. He didn’t want to go back to Haiti simply as the puppet of the United States. He wanted to make sure that when he got back, he would in fact ultimately have a free hand in governing the country, so he was somewhat leery on those grounds.

Overall, it went better than [the U.S. intervention in] Somalia, but it was a more benign situation.

But there were still big gaps in our ability to plan and execute these types of missions. The existing Haitian institutions were ineffective, corrupt, discredited, and to the extent they did policing, they did it in an abusive fashion, which we couldn’t tolerate once we were in charge.

For instance, the Haitian police, who were actually military, arrived to disperse the crowd and did so in their usual fashion, by knocking them over the head or shooting them, and they did that in front of CNN, and that was broadcast back here, with U.S. soldiers just sort of looking on while the human rights abuses were seen.

That immediately caused the White House to tell the military to get some military police down there. The next day, they flew down and the U.S. military mobilized civilian police and took over responsibility for overseeing the Haitian police. Special Forces units were dispersed throughout the countryside and did a good job of establishing security out there.

“The situation then gradually began to deteriorate, until in 2004, the U.S. had to intervene once again”

We had a good plan to establish a new police force. We vetted that with Aristide beforehand. We had the assets and the people. We opened a police academy. We began recruiting. Pretty soon we were pumping out several hundred new recruits in a fairly comprehensive training program, and eventually we trained about 5,000 of them over a two-year period. That was quite a successful program.

We did nothing comparable to reform the judicial or penal systems, and so the police eventually became immured in a basically corrupt system and the reforms had only limited long-term effect, but it was at least a relatively successful short program.

There was still a big dispute about what we would be doing with the military. Our intentions had initially been to reform and retrain the Haitian military. Aristide preferred to disband it, and we eventually went along with that, and it was disbanded completely and never replaced, so Haiti doesn’t have a military. It just has a police force.

We eventually succeeded in holding elections on schedule, both elections for a new parliament, and then eventually elections for a new president. The opposition decried them as unfair. Some didn’t run. Some ran and then disclaimed them as having been unfair. I think most neutral observers felt that they were poorly run, but fair as things go.

As for Aristide, he was initially attracted to the idea that his five-year term should not count the three years he had spent in exile, and there was some logic to that, but we wouldn’t accept it, largely because of what we knew would be the reaction from the Republicans here. The Republicans had secured control of the Congress four or five weeks after the intervention, so they were on a much stronger position.

We, along with elements of his own party, required Aristide to step down, five years after he had originally entered office, even though he had three years of exile. And his response was to run a candidate who would take orders and do nothing for five years until he could run again.

We left within the timeframe we said we would leave, which was two years, by which time the situation was peaceful, they’d had elections, but most of the underlying reforms that would have made this of long-term value had not been put in place.

The situation then gradually began to deteriorate, until in 2004, the U.S. had to intervene once again.