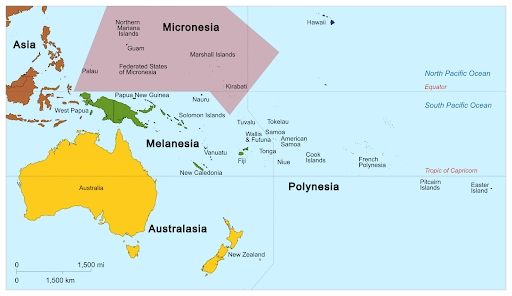

The Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), sometimes known simply as Micronesia, consists of four states — Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei and Kosrae – spread across the Western Pacific Ocean. They are north of Australia, south of Guam, west of the Marshall Islands and almost 2,500 miles southwest of Hawaii. Together, the states comprise 607 islands spread across a distance of almost 1,700 miles. The capital is Palikir, located on Pohnpei Island. The first Micronesians settled on the islands 4,000 years ago.

The FSM was formerly a part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, (TTPI), a United Nations Trust Territory under U.S. administration, but it formed its own constitutional government on May 10, 1979. FSM became a sovereign state after independence was attained on November 3, 1986 under a Compact of Free Association with the United States.

Among those who have served at the U.S. Embassy in FSM, Larry Dinger is a graduate of Macalester College, Harvard Law School and the National War College. After serving in the U.S. Navy and practicing law, Dinger joined the Foreign Service in 1983. Dinger was ambassador to the Federated States of Micronesia from 2001 until 2004. From 2005-2008, he was Ambassador to the Republic of the Fiji Islands, the Republic of Kiribati, the Republic of Nauru, the Kingdom of Tonga and Tuvalua, and from 2008-2011 was the U.S. Chargé d’Affaires to Burma.

Larry Dinger was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy in March 2014.

To read more about East Asia, post-colonialism or to read the oral history of John Dinger, please follow the links.

“ I was still an FS-1, too junior to be thinking of ambassadorships”

Larry M. Dinger, Ambassador to the Federated States of Micronesia, 2001-2004

DINGER: As described, my family and I really enjoyed Kathmandu and would have happily stayed for three years; but in May of 2001, when I had been there about nine months, the principal deputy assistant secretary in the East Asia Bureau, Tom Hubbard, phoned me one day and asked if I’d like to be ambassador in Micronesia. (Larry Dinger is seen at left.)

I was still an FS-1, too junior to be thinking of ambassadorships. From my perspective, it came up completely out of the blue, and we were so content in Nepal…

One ought to leap at the chance to be an ambassador, but I had to stop and think about it a little bit and talk to my family. We did talk, and concluded that I couldn’t miss that opportunity. So I said yes and began the Washington systems process of getting to an ambassadorship…

Micronesia is scattered just north of the Equator between Hawaii and Guam, but a little farther south. It has many islands, I’ve forgotten just how many. The ocean area that surrounds those islands, is about the size of the continental United States.

It’s a vast region. But the total population is just over 100,000 people. The islands became toys in the colonization game. The Spanish began it. They worked from the Philippines, and moved north and to the east. They brought the Catholic religion with them…

The Federated States of Micronesia these days consists of four states. From west to east it’s Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei, and Kosrae. The Micronesian region also includes the nation of Palau, which is a little farther west and south, and depending on how you define it, the U.S. territories of Guam and the northern Marianas.

But the Federated States of Micronesia, the four states where I represented the United States, were the ones I mentioned. So the Spanish colonizers came through from the southwest and made it as far as about Pohnpei.

From the east, American missionaries, affiliated with the Congregational Church in particular, also arrived and made inroads in Kosrae and also in Pohnpei, so there’s a bit of a religious overlap there.

After the Spanish lost the Philippines during the Spanish American War, the Germans who had other Pacific colonies arrived. The Spanish had been pretty rough colonizers; the Germans also were not subtle. The Germans were there until after World War I, and then the Japanese became the also-harsh colonizers until World War II.

There were no land battles in the Federated States of Micronesia during World War II, but a famous U.S. aviation strike on the Chuuk (Truk) Lagoon sank a bunch of Japanese ships.

Scuba divers still go down to look at those ships in the lagoon, as I did. They’re within range of scuba. So the U.S. drove the Japanese out in World War II and took over Micronesia. It was the U.S. Navy initially that had charge of our colonization effort there.

Then in the 1950s the Department of the Interior became the chief U.S. agent. And U.S. colonization continued until independence movements gained strength. In the early 1980s, we came to an agreement on a compact of free association which gave independence to the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) within some limits.

The United States retained the right to both defend Micronesia militarily if need be, and to utilize Micronesian lands, seas, and ports for military purposes if need be. We’ve never taken up that use for military purposes, although during World War II American navy forces had used anchorages in some atolls, Ulithi in Yap state and perhaps in other places as well…

Once the compact of free association was agreed to, Micronesia began to run its own affairs. But the United States continued to provide a very hefty amount of assistance. By the time I got there in the beginning of 2002, the U.S. assistance per year was well over 100 million dollars, and as I say, the population was just over 100,000. So it was a huge per capita investment of U.S. funds.

“The American ambassador in Micronesia was really a big fish in a small pond”

The American ambassador in Micronesia was really a big fish in a small pond. There were three other embassies: the Japanese, the Australians, and China, but the United States had by far the biggest stake. The U.S. Embassy in Kolonia is seen at right.)

While I was there the process was under way for negotiating the second compact to replace the initial one. I think there was pretty universal agreement that the first compact had not succeeded in bringing Micronesia to fulfillment as a truly independent country. An awful lot of dependency had continued, in part because of the huge amounts of money the United States was providing.

Also, supervision of the expenditure of the funds had been difficult, with a very small U.S. Embassy in the FSM which had only one full-time, on the ground Department of Interior overseer, a guy who was knowledgeable and hard working but could not possibly be everywhere all the time.

Also non-monetary assistance from the Department of Agriculture, Department of Education, Department of Health and Human Services and others in Washington had often not been very effective. Programs designed for U.S. states often didn’t fit well with the needs and capabilities of much less developed Micronesia.

I think I probably shocked some folks when I used a Department of Education invitation to address the annual DOE regional gathering of teachers and administrators from Pacific Island jurisdictions, an audience of several hundred people flown in that year to Pohnpei and housed at USG expense, to note the high cost of such events to the U.S. taxpayer; to suggest the funds probably should have been used instead, at least in the FSM, to repair incredibly decrepit schools, buy text books, provide basic training to teachers, etc; and urged the conference attendees, when they returned home, to spread widely whatever valuable knowledge they gained.

My visits to health centers in the four states, like my visits to schools, made abundantly clear that huge amounts of U.S. funding over several decades had not brought state of the art, not even adequate, systems. Such realities were among the reasons a significant migration of FSM citizens to the U.S. had taken place.

Under the compact, FSM citizens are allowed passport-free entry to the U.S. and can stay as long as they like as non-immigrants. Many have done so. In Chuuk, in particular, many if not most families had bread winners living in Guam, or Honolulu, or somewhere on the mainland.

Tyson Foods in Arkansas had a big contingent of Micronesian workers. I remember the Governor of Hawaii, Linda Lingle, asked me to stop by her office to discuss her concerns about the significant population of Micronesians living there, usually under-educated, sometimes dependent on Hawaii services. So results from compact one had been disappointing, and there was a desire to create a better system for compact two. I was involved in the process of the negotiations, but I was not the chief negotiator.

“Supervising an FSM program from Honolulu would, geographically, be the equivalent of supervising a Kazakhstan program from London”

One of my highest priorities was to bring more direct Department of Interior oversight to its FSM programs. DOI, too, wanted to increase oversight and had plans to establish four positions in the region to do so. However, I found out that the plan was to create an office in Honolulu, rather than in Pohnpei and/or Majuro or both.

That was maybe marginally better than trying to supervise programs from Washington or San Francisco, but Honolulu was still far away. I lobbied as best I could, including by sending a telegram pointing out that supervising an FSM program from Honolulu would, geographically, be the equivalent of supervising a Kazakhstan program from London or an Argentina program from Washington. Just too far away.

However, Interior staff, some of whom would be taking up the new jobs, insisted on Honolulu, and senior levels at State declined to battle Interior about that fund management detail. (A Yapese woman in traditional dance costume at right.)

I lost, the office eventually opened in Honolulu, oversight visits took place somewhat more frequently than before; but, in my view, a real opportunity was missed. In some other respects, compact two did bring improvements, including creation of a trust fund, with annual U.S. contributions intended to, by the end of compact two, have in place a permanent nest egg, which would allow annual U.S. contributions to end…

As I mentioned, one person from the Department of Interior was resident at my embassy. It was a very small embassy with the one Interior person, myself, my DCM, an OMS, and one additional Foreign Service Officer type who did a combination of consular and some management duties, plus some excellent local hires.

“The hardest post for my family”

Kolonia was certainly the hardest post for my family of any. When we left Nepal my oldest child, my daughter, was halfway through her senior year of high school, my second child was halfway through his junior year, and my youngest was moving toward junior high.

We told all three that we would arrange for them to go to boarding school somewhere if they wanted to. There were schools in Micronesia, but they weren’t reputed to be all that strong. But all three of the kids decided they wanted to come with us. I don’t think they quite realized how difficult the schools would be, but they wanted to come and so they did.

The school we ended up putting them in was a Seventh Day Adventist school, which was the best on the island. But it was not a superior school by any means. I think it challenged my kids to think in different ways, so that supposedly was good. But it didn’t have much to offer for activities, and some of the teachers were very narrow in their perspectives and they had very limited teaching-education backgrounds. That was tough.

And Pohnpei did not have a lot of beaches. If you were a scuba diver, opportunities abounded. If you’re a fisherman, that was great. No golf courses, nothing like that. Pohnpei had a lot of very nice people and a small town environment — I grew up in a very small town, if you recall — and in that kind of environment you do make friends. And so we made lots of friends in Micronesia. But it was not simple and we had to struggle some.

“Suddenly I heard a ka-boom and the windows rattled on my house”

The Japanese had an embassy. In fact, that came into play. One of the things that the U.S. did to help out was, if unexploded ordnance from World War II appeared, we would bring in some military personnel to take care of it.

At one point while I was in Kolonia, an effort was underway to refurbish the sporting facilities in preparation for a regional sporting event. When they started to redo the baseball park and dug just a few inches below ground they came upon ordnance, almost certainly Japanese ordnance from World War II. And the more they dug the more they realized they were coming into lots of ordnance.

They ended up, as carefully as they could, picking it all up and moving it into a cave very nearby, a cave which happened to be almost directly underneath the Pohnpei state legislature building. The legislature then could not meet, fearful of going up in an explosion, until somebody could come to take care of it.

We arranged for U.S. Navy EOD experts come out to resolve the problem. They were going to do controlled explosions in a remote part of the harbor on a weekend. I was sitting up at my place, which was quite a ways away from downtown Kolonia, on a Sunday morning when suddenly I heard a ka-boom and the windows rattled on my house.

The folks who were doing the detonation had moved the rounds out along the causeway toward the airport and then off into the ocean on the side. But they either had not realized how potent the explosives were, or they had miscalculated how far away they needed to be. The explosion shattered windows and knocked down furniture in the buildings back in town that were nearest, and the nearest building was the Japanese embassy.

So, in effect, we had a repercussion from World War II at that point…

“Spam is a huge seller”

Some American products sold very well. Spam is a huge seller. In fact, when I was on R&R from the FSM, I visited the Spam museum in Austin, Minnesota, the Hormel Company, not far from my hometown.

One of the displays reported that the FSM and Guam, on a per capita basis, are the biggest consumers of Spam in the world. That gave me an idea for the next year’s Christmas presents. I asked if I could buy some of their insulated coffee mugs, blue mugs with yellow spam labels, to take back and give out as gifts.

The manager offered: “We’ll give them to you. That’s great advertising for a place where we sell a lot of Spam.”

I said, “Well, I’ll have to check with the ethics folks first.”

So I went back to L (State Department Legal Office) and checked.

And they said, “Since Spam has no American competition in that market, it’s not a problem.” So I spread the gift mugs around.

“For the first time in my life I was sakaued out”

There weren’t a whole lot of other distinctly American products in the FSM, but many American products got there one way or another. Most automobiles were used Japanese vehicles with right-hand drive. So the FSM was a left-hand drive country with right-hand drive vehicles. That seldom made any difference at all though because the traffic pace in Pohnpei was snail like.

Mostly because so many people were either mellowed out on sakau, the Micronesian version of kava, same root but squeezed through the slimy bark of a type of hybiscus bush, or they were chewing betel nut and needing to open the door frequently to spit.

The roots of the Kava plant are used to produce a drink with sedative, anesthetic and euphoriant properties. Kava is consumed throughout the Pacific Ocean cultures of Polynesia…

While I was in Micronesia, my brother [John Dingle] was already ambassador in Mongolia. We were the first two career Foreign Service Officer sibling ambassadors ever. My brother checked that out with the State Department historian (laughs).

State Magazine, the State Department’s magazine, wanted to do an article on us, so they asked us each to provide pictures from our environs. John ended up sending pictures of standing in a winter wasteland in Mongolia holding up a block of frozen milk. And I wanted to show tropical Micronesia.

I mentioned the article to the guy who was the speaker of the congress at the time, Pete Christian. Pete was rather a controversial person, and I didn’t always get along great with him. But he was interested in helping me out and maybe in getting some free publicity for the hotel he owned in downtown Kolonia which had a great view right over the harbor to a massive outcropping called Sokehs Rock.

Pete suggested that we get together in the evening at his hotel just before sunset and drink sakau. A photographer could take pictures of us with the view in the background. Sounded like a good idea to me. So we sat, got photographed, and had a good talk.

When we finished, the next thing I had was a meeting of the veterans’ group at the same hotel. Micronesians not only receive aid from the United States, but they also have the opportunity to serve in our armed forces, and many do. Some have died. I went to several funerals of Micronesians who lost their lives in the Iraq War. And I came to know one young man who came back missing both legs and an arm. So Micronesians have made sacrifices.

Kolonia had a very active veterans’ group, and, as a veteran myself, I frequently joined their gatherings.

I walked over to the hotel’s outdoor bar to join them and I suddenly realized that Pete Christian must have given me some of his very best sakau because for the first time in my life I was sakaued out. Previously I had never really felt more than a tingle of my lips, but this evening I was thirsty, saw a glass of water in front of me, and I tried to move my hand to the water, but it was the slowest process.

I could barely get my hand over there and I was not at all sure I could pick the glass up and bring it to my lips. The veterans around me, both American and locals, all realized what was going on. They were very understanding. I mean they’d been to that point many times before.

They said if you want to lie down, you can. If you want to sit here, you can. If you want us to give you a ride home, we’ll do that.

I said, “Well, I’m fine except I just can’t really do much. How long does this last?”

They estimated it would be an hour, hour and a half, something like that. So we continued with the session at the bar and eventually the sakau wore off well enough that I was confident I could drive myself.