In the aftermath of the 1994 Rwandan genocide, ethnic Hutu refugees — including génocidaires — who had crossed into East Zaire to escape persecution from the new Tutsi government carried out attacks against ethnic Tutsis from both Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) and Rwandan refugees. The Zairian government was unable to control the ethnic Hutu marauders, and indeed lent them some support as allies against the new, Tutsi-led Rwandan government. In response, the Tutsis in Zaire joined a revolutionary coalition headed by Laurent-Désiré Kabila. Kabila’s aim was to overthrow Zaire’s one-party authoritarian government run by Mobutu Sese Seko since 1965. With Kabila’s forces on the march, Zaire was soon engulfed in conflict. These hostilities, which took place from 1996-1997, are known as the “First Congo War” and lead to the creation of Zaire’s successor state The Democratic Republic of Congo. The United States, who had supported Mobutu until the end of the Cold War, recognized how potentially dangerous the situation was as Kabila gained control of most of the country and advanced rapidly towards the capital city of Kinshasa. In 1997, the United States sent a small group of diplomats to broker negotiations and attempt to come to a peaceful agreement between Mobutu and Kabila.

In the aftermath of the 1994 Rwandan genocide, ethnic Hutu refugees — including génocidaires — who had crossed into East Zaire to escape persecution from the new Tutsi government carried out attacks against ethnic Tutsis from both Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) and Rwandan refugees. The Zairian government was unable to control the ethnic Hutu marauders, and indeed lent them some support as allies against the new, Tutsi-led Rwandan government. In response, the Tutsis in Zaire joined a revolutionary coalition headed by Laurent-Désiré Kabila. Kabila’s aim was to overthrow Zaire’s one-party authoritarian government run by Mobutu Sese Seko since 1965. With Kabila’s forces on the march, Zaire was soon engulfed in conflict. These hostilities, which took place from 1996-1997, are known as the “First Congo War” and lead to the creation of Zaire’s successor state The Democratic Republic of Congo. The United States, who had supported Mobutu until the end of the Cold War, recognized how potentially dangerous the situation was as Kabila gained control of most of the country and advanced rapidly towards the capital city of Kinshasa. In 1997, the United States sent a small group of diplomats to broker negotiations and attempt to come to a peaceful agreement between Mobutu and Kabila.

Marc Baas was an American Foreign Service Officer who served at a variety of different locations in Africa from 1972 to 1998, including Tunisia, Gabon, Zaire, and Ethiopia. Baas was part of the small group of diplomats that were sent to broker negotiations in Zaire and was there until the fall of Kinshasa in 1997. Baas continued to serve as the Director for Central African Affairs in Washington D.C. for one more year before moving to the Economic Bureau. He retired in 2001. Below is an excerpt of his interview, conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy in November 2005.

Please follow the links to read more about the Democratic Republic of Congo, African politics, negotiation diplomacy, or Marc Baas’s full oral history.

“Our focus was was very much trying to prevent the implosion of Zaire”

Marc Baas, Director for Central African Affairs, 1996-1998

BAAS: Mobutu was clearly nearing his last days as President of Zaire. He was sick, it was clear he was dying, but nobody knew of course when he was going to die. At some point, and I don’t remember the date, at some point the Rwandans supported Kabila out in the east and he rose up against Mobutu. He had been out there for 30 years as a minor warlord..jpg)

He hadn’t really done much, but finally as the situation on the border with Rwanda became very confused and eventually everyone went back into Rwanda, he started going the other way and it turned out the FAZ, the Zairian armed forces, les Forces Armées Zairois, was a shell and was not able to do much. He moved very quickly, helped by the Rwandans, from east to west across the country.

Our focus was very much trying to prevent the implosion of Zaire, trying to find a peaceful resolution to the problem, and trying to convince Mobutu that maybe a negotiated transitional government would be a better way to go than simply losing power.

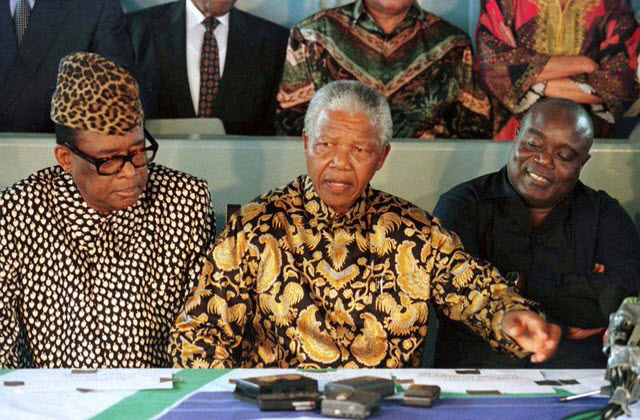

We had a couple major external negotiators involved. Bill Richardson was one of them, who I had met first in Gabon many years ago, when he was a Congressman from New Mexico. He and I and a bunch of other people went out and flew about the continent talking to a variety of people about the issue. We saw Mugabe, we saw Museveni, we saw Mandela, we saw Dos Santos in Angola, and we saw, of course, Mobutu.

Eventually, after some effort we arranged to have a South African ice cutter come up to Pointe Noire in Cameroon and take on Mobutu and Kabila and hopefully lead to a negotiation. The reason we ended up on an ice cutter is because neither of them wanted to meet the each other on African soil.

“So we figured if we got on a neutral ship, neutral to them, sailing in international waters, maybe this would work out”

South Africa had an ice cutter they didn’t need at the time, because of global warming or whatever, and it was available. It’s rather amusing that it was an ice cutter in Central Africa.

The reason we ended up trying to get something done on a ship was because neither side wanted to come together, neither wanted to go to each other’s area, and neither one really wanted to leave their base. There was great distrust between Mobutu and Kabila. So we figured if we got on a neutral ship, neutral to them, sailing in international waters, maybe this would work out.

Well, in the event Mobutu got on board. When Mobutu came through Pointe Noire, and although I had known Mobutu for a long time, it was still remarkable to see him at the airport in Pointe Noire and all the Congo, a different Congo, not his Congo, the Congo with its capital in Brazzaville, was out there just really cheering and obviously respecting this guy as someone who was a big man, and respected as a big man for all of his warts and faults. He got on the boat and we were sailing out to sea and Kabila was supposed to come, fly out by helicopter once we were in international waters, but at the last moment he bailed out and that was unfortunate.

“Kabila wasn’t coming”

One amusing thing is we were running around the boat talking, Mandela was on board, we were talking to the South Africans and trying to prepare things for when Kabila showed up. Bill Richardson was there, and finally we got word from the captain of the boat, who I guess heard on the radio that Kabila wasn’t coming.

Richardson told the Foreign Minister of South Africa that this was the case and then Richardson went off to go meet with someone else and I was still there. The Foreign Minister looked at me and said, “Well, would you tell Mandela?” I said “Shouldn’t you do that, Mr. Foreign Minister?” He said, “Well, I’d feel better if you did it, hear it coming from an American.” OK.

This was like three o’clock in the morning, so I went into Mandela’s room and, after knocking, I think I got him out of bed. He came out and I told him what had happened and what we knew and he said, “Oh, that’s awful. What should we do now?” I said, “Obviously, from the political point of view, in terms of trying to put together something between Kabila and Mobutu, we’re going to have to go back to square one. I think for the moment what we ought to do is probably turn the boat around because we’re still sailing out away from the African continent toward international waters. Let’s go back to Pointe Noire and reconvene in the morning.” He said, “Oh, yes. That’s a good idea. I think we should do that.” He gave orders and the boat turned around and we ended up back in Pointe Noire. That was a big issue.

“[Mobutu] truly believed that he had been a wonderful president”

We saw Mobutu a couple of times, we saw Kabila a couple of times, once in Lubumbashi after he captured Lubumbashi, down in the southeast. All of our efforts to come up with some sort of transitional government, as a way station to a new election and a new government without Mobutu, simply failed.

As I said earlier when we were talking about Zaire, I personally think that up until this point Mobutu could have had an election and could have been elected as president in a fair and free election in Zaire. But at this point, no. I think part of the problem was that Mobutu, either he saw that he was losing and wanted to go down sort of in style, on his horse, to the bitter end, or stretch it out as long as he could, or he didn’t believe he could actually lose, he didn’t believe that Kabila would be able to capture Kinshasa…

…He was not prepared to accept that after, whatever it was, 25 years, somehow the Zairian people wouldn’t stand up and defend him. He truly believed, and with some reason, that he had been a wonderful President for Zaire. He didn’t recognize that there was a very good argument that could be made he’d been a terrible President for Zaire.

Probably the truth is somewhere in between. He had done some things that were very good, like provide stability and hold the country together. He had done some things that were very bad, like steal and not allow the economy to develop and not allow democracy and so on, not so much torturing and murders as in many other countries…

…One of the arguments that I used with him, when I was there with Richardson, was look you can truly be the father of your country now. You’ve held this country together, you’ve created something called Zaire, which really didn’t exist before. You have ruled it effectively for a long time, you are coming to the end of your life and if you have elections, and if you have good elections you can bequeath democracy to your country. All you need to do is agree to step aside for a transitional government, and then we can have elections and you will have been the godfather creating democracy. I said, that’s not all bad. Your reputation will be much different with that as your final note. It didn’t persuade him

“One thing we did succeed at… Kinshasha fell relatively quietly”

From Kabila’s point of view he was winning, he had captured virtually 90% of the country with very little effort on his part. He had the help of the Rwandans behind him, who were trying to solve their problem of the Interahamwe. They thought Mobutu was supporting the Interahamwe. There was no real reason for Kabila to negotiate…

…The Interahamwe were the group that was supporting the previous genocidal government in Rwanda, military and security folks who had left Rwanda when the Tutsi liberation force came in. They had all left and gone to eastern Zaire, and they were using eastern Zaire as a base for attacks on Rwanda, which was why Rwanda was helping Kabila get rid of Mobutu, because they thought Mobutu was helping the Interahamwe against the Tutsis…

…So it was sort of like the First World War and Sarajevo, but it was all sort of connected together there. The Interahamwe were some bad guys. These were guys that had killed a lot of people.

The one thing we did succeed at was when it fell, Kinshasa fell relatively quietly. There was no massive assault, there was no loss of life, or huge loss of life. It was a relatively benign affair because the generals to whom our embassy, Dan Simpson was ambassador, and others had been talking, and who we had been talking to by phone, accepted the inevitable and basically decided not to fight.

General Mahélé was the leader of that group and he was subsequently killed by some of the diehard troops of Mobutu. He actually did a terrific service to his countrymen.

Then Kabila took over and, of course, then it was a matter of talking to Kabila and trying to figure out what our policy was going to be towards him and could we get him directed in the right way. He started out OK, but he clearly didn’t have the gravitas or the kind of political acumen that Mobutu did.

I personally think he just wasn’t up to the task of running the country. He could sort of maintain order in Kinshasa and some other parts around the country, but he really wasn’t up to the task of running a country.

Well, after I left, eventually he was assassinated and now his son is in power. As I say, that took a lot of time. There were a lot of meetings in Washington about what to do about the refugees, about the war, how to stop the war, plotting where the war was, again, mixed in with Rwanda and the Interahamwe.