Described by one reporter as “a biblical famine in the 20th century,” the 1983-1985 Ethiopian famine was a humanitarian crisis that was initially little known to much of the rest of the world. For six months, General Mengistu Haile Mariam, the leader of the military junta ruling Ethiopia, refused to acknowledge the famine–even as millions of people starved. When USAID Administrator Peter McPherson visited Ethiopia at the height of the famine, he was appalled by the scope of the suffering. And he resolved to take action.

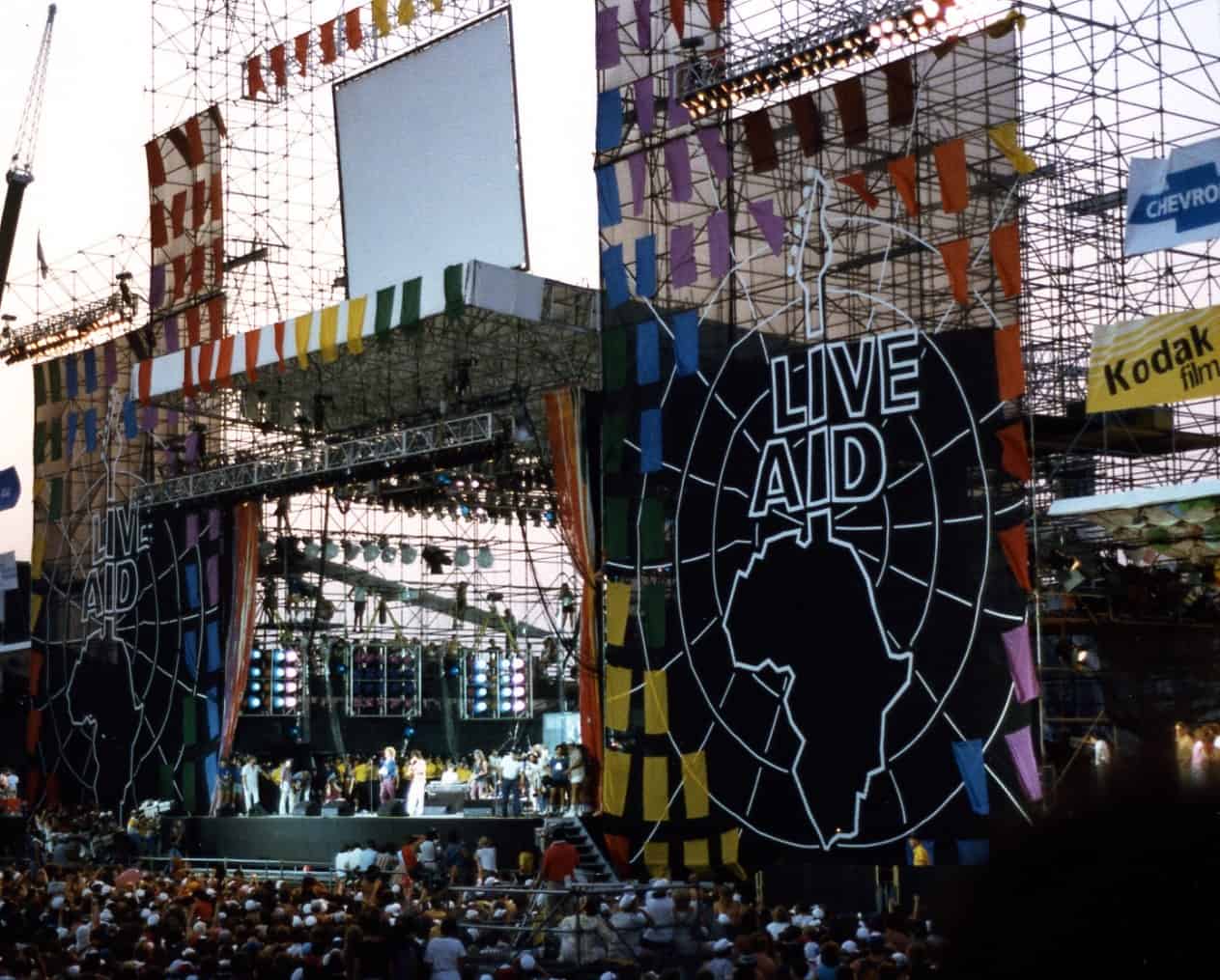

Back in Washington, McPherson met with President Reagan and showed him photographs of the famine. In an Oval Office meeting, Reagan agreed to overlook political differences with the Mengistu regime and uttered the famous words, “a hungry child knows no politics.” U.S. policy changed, and the aid began to flow. The Live Aid concert and expanded press coverage solidified public engagement and support. But McPherson’s engagement with Reagan was also critical.

McPherson returned to Ethiopia and was again outraged, this time by delays in food delivery. USAID hired its own vehicles to transport food aid from Ethiopian ports to people in need. Other donors relied upon the Mengistu government to transport the food, and refused to publicly hold the government accountable when the vehicles did not show up. McPherson asked a colleague to surreptitiously photograph other donors’ clearly-marked food assistance lying uncollected at the ports. Armed with photographs of wasted food and visible donor names, McPherson gave local ambassadors a choice: join USAID in issuing a public call to action or be embarrassed before a global public that was finally beginning to pay attention to the crisis. Days later, a press conference was held and the food began to move.

During his tenure as Administrator of the United States Agency for International Development (1981-87), Peter McPherson combined realism and idealism to protect USAID from budget cuts, a loss of relevance, and domination by the State Department. He worked on diverse challenges—from family planning in China to economic policy in Egypt—and was equally adept in political battles as in meeting the challenges of promoting development and providing humanitarian aid around the world.

Peter McPherson’s interview was conducted by Alex Shakow on April 8, 2018.

Read Peter McPherson’s full interview HERE.

Drafted by Lydia Laramore

Excerpts:

“It [the famine] was difficult to verify because of the isolation, and the Mengistu regime did not want information out.”

Famine and Isolation in Ethiopia: So, here’s what happened. Sometime late ’83 or ’84, more and more stories about huge food shortages and pending famine were beginning to come out of Eritrea and Tigray, then part of Ethiopia. It was difficult to verify because of the isolation, and the Mengistu regime did not want information out. We had a mission there. Their travel was restricted and, in any case, we had difficulty knowing what was going on.

“A hungry child knows no politics.”

Convincing Reagan: In any case, we started to provide food but not nearly enough. Senator Danforth of Missouri was able to get into the country and look at the situation. I went with him to see the president.

. . . . The Ethiopian government didn’t really want the food delivered. They did not say that but tried to delay the food in many ways. When I got back from my trip . . . I immediately went to see [the president] and showed Reagan the pictures and talked to him about what I saw.

The government of Ethiopia tried to keep the disaster news from getting out, and tried to slow down the delivery. But certainly, the Soviet ties and distrust of the Ethiopian government made it harder in Washington. Public interest (Bono with his whole world effort was starting to be a big help in public concern), the Danforth report, and my trip and report to the president broke the dam in moving the food. I showed my terrible pictures to Reagan in the Oval Office. Baker, Meese, and Bud McFarland were all there. That is where Reagan said “A hungry child knows no politics.” I came out of that meeting and quoted the president to the press. Those words established the U.S. policy.

“It was outrageous for the food to be wasting away while people were starving.”

Blackmailing diplomats: There is a great story about some of the other donors to Ethiopia. We took much of our food in with our own trucks because, as I said, we couldn’t depend upon the Ethiopian government transporting the food. There was this serious question as to whether Mengistu really wanted to get the food to the region. Something like Stalin in Ukraine in the ‘30s.

Q: So, political opponents you don’t have to feed them.

Yes. So we brought our own trucks and had NGOs deliver the food. But the Europeans, Canadians, and Japanese brought food into the port in Ethiopia and waited for the Ethiopian trucks. The government trucks did not come and a lot of their food just sat in the port. We suggested to these donors that we all have a joint press conference demanding the trucks from the government. The other donors were not willing to be so public in their demands. So, I sent my Deputy Administrator Jay Morris to Ethiopia to see what evidence/photos he could get on the food in the port.

It was great to be at AID. The State Department probably would not have agreed to this kind of thing. We just did it. Jay went to the port and surreptitiously took pictures of the food in the port. The food had been there for a few weeks; there were huge piles of bags of food out in the open air and some of the bags had broken open. The bags had the name of the donor on them and some of this writing could be read in the pictures. It was outrageous for the food to be wasting away while people were starving

Anyway, Jay brought back a lot of pictures of the big piles of bags, many of them split open and with the donor name still viable. I invited the ambassadors from all the donor countries to my office, and I gave them the pictures of their food.

I asked the group again to hold the joint press conference. One of the ambassadors asked the question on all their minds. He said, “I guess you probably have other copies of these pictures?” I said yes. They said they did not want the pictures released and would promptly consult their governments.

I knew most of my counterpart development heads, and I believe most of them were willing to hold the press conference. But their governments were not as aggressive. I did get a call from one of the donor heads saying that her government had directed her to tell me that it would be an “unfriendly act” for the U.S. to release the pictures. Of course, I had no interest in releasing the pictures. I just wanted the donors to be much more aggressive with the Ethiopian government including holding the press conference.

Within a few days we had a very good joint press conference.

Mengistu then delivered some trucks. Not all that we wanted, but a lot, and the other donor food started to move.

“The people of Ethiopia appreciated the help of the U.S.”

Grateful cab drivers:As you know we have a lot of Ethiopian cab drivers here in Washington, D.C. some of whom at the time of AID’s famine effort even recognized me.

Q: Without prompting.

MCPHERSON: Without prompting.

Very, very few U.S. citizens would recognize an AID Administrator. The people of Ethiopia appreciated the help of the U.S.

Q: They loved you.

MCPHERSON: Not me personally but they deeply appreciated the people of the United States. They loved what we did.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

MBA, Western Michigan University 1966–1967

JD, American University 1967–1969

Peace Corps in Peru 1964–1965

Special Assistant to President Gerald Ford 1975–1977

Administrator of USAID 1981–1987

Preserving USAID’s budget and influence

Family planning

Ethiopian famine

Relationship between USAID and the Hill

Policy reform in developing countries

Deputy Secretary of the U.S. Treasury 1987-1989