On December 2nd, 1979, thousands of anti-American demonstrators attacked the U.S. Embassy; protesters broke down the door and set fires that damaged the lower floors. Political Officer James Hooper and other American officials inside the embassy hurriedly attempted to shred sensitive information before sneaking out past an angry mob, one by one, through a back entrance and onto the streets.

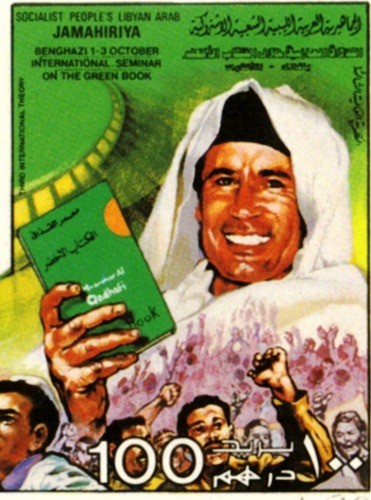

In the wake of the attack earlier that year on the U.S. Embassy in Iran and hostage crisis, relations between the United States and Libya had become increasingly strained by the continuing radicalization of dictator Muammar Gaddafi. Those at the American Legation in 1979 feared that there were Libyans, either within Gaddafi’s government or among the general populace, who would attempt to replicate the events of the Iranian hostage crisis. The situation quickly unraveled when rumors began circulating that the United States was involved in an attack on the Great Mosque of Mecca. Within hours, the demonstration in front of the American Legation spiraled out of control and led to the burning of the embassy. The U.S. had already withdrawn the ambassador to Libya in 1972. Following the attack, all remaining U.S. government personnel departed. The embassy remained closed until 2004, when a diplomatic U.S. presence was resumed.

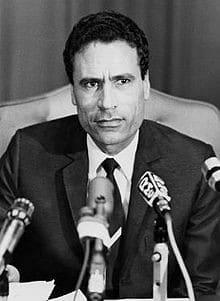

James R. Hooper served as a political officer at the embassy and observed the political tensions that had built up before the attack. He had attempted to improve the security of the legation to prepare for what he saw as an inevitable confrontation with the Libyan population. In order to ensure the safety of the embassy and its staff, Hooper acted against the orders of his superior officer who refused to acknowledge the danger of the situation. Thankfully, the attack resulted in no fatalities or hostages. Hooper went on to serve in the United Kingdom, Kuwait, and Poland.

James R. Hooper’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on October 26, 2006.

Read James R. Hooper’s full oral history HERE.

Drafted by Wendy Erickson and Hunter Matthews

Excerpts:

“And the staff started getting very nervous. Many of the families wanted to leave.”

Warning Signs: There were the hostages [in Iran] and no one knew what Carter was going to do at the time, this was before the failed rescue mission, and anything was possible. . . . [W]e started to monitor demonstrations taking place in various Libyan towns against the U.S. And the demonstrations began moving from the south, getting ever closer to Tripoli and there seemed to be a pattern here. And the staff started getting very nervous. Many of the families wanted to leave.

Bill [William Eagleton, the embassy’s chargé d’affaires who headed the embassy in the absence of the ambassador] found this an awkward time, because this was going to undermine our effort to improve relations and try to get somewhere. And I think he actually tried to talk some family members out of leaving, which was not welcomed by them. He minimized the import of these demonstrations and I was trying to focus him on, “I think something is possible here. I’m not saying something will happen, but the odds of Gaddafi doing something unpredictable are rising.” But he didn’t think it was likely at all.

I said that we needed to have an evacuation drill at the embassy to make sure the staff knew what to do if there was an attack. Bill disagreed, so we organized the drill on the weekend without his permission or knowledge. . . . We all pretty much concluded that Bill had his head in the sand and we had to act on our own.

“We understood enough of what they were saying—“Down with the Americans”

The Attack Begins: Shortly thereafter an American came to the embassy and said, “There’s a group of people moving down the street.” So Jack McCavitt and I decided to follow this crowd down to Green Square, the main square downtown. . . . We got there and they were whooping it up and the crowd was becoming more emotional. We understood enough of what they were saying—“Down with the Americans”—and there were the signs and we could read enough of it to figure it out things were bad. And then it was “On to the embassy!”

We started running to be ahead of the crowd, to get back there in time to warn the others. . . . We got back to the embassy just a few minutes ahead of the outriders of the crowd and said, “Quick, get the protective grills down!” We were just getting it down with some effort and those inside who wanted to get away quickly scampered out the door. We pulled the steel shutters over the doors. The windows were barred.

In an experience like that, I’m sure I was scared through all this, but I don’t remember being scared at all, because with one exception all of the staff acted very well. . . . All of us who were in there know this, but it hasn’t really been said before, so it’s very awkward, in some ways to describe this, but [Bill] fell apart. He lost it. He was no help to us. . . . Because he had never thought it was going to happen, he was not mentally prepared for the attack. If you think something might happen and prepare yourself and run through some drills, you’re psychologically better prepared for what comes.

. . . And we held them off, we moved up from the first floor to the second floor. On the second floor our admin officer, John Dieffenderfer, who was just a great guy, a real hero, he saw someone knocking an air conditioner out of the wall and then was gonna climb in through the hole. He went and pushed the guy back out.

“. . . we assumed the whole thing was going to be lost.”

Destroying the Evidence: We started destroying documents. We’d been destroying them before but had not finished. . . . We did not have shredders. We had these things that had a big barrel and had like a fan, we’d put stuff in and crunch it up. I was trying to do that part at the end.

We were now back in the vault area getting rid of lots of these papers, because we assumed the whole thing was going to be lost. And I didn’t know, because I hadn’t done it before, that you have to turn on the vacuum pump to get the document destruction mechanism working. So the shredded paper in there was building up. When the paper reached the top of these two barrels they both stopped working. We couldn’t shred any more documents.

Because of the air conditioning vent system throughout the embassy, the tear gas from the canisters we had thrown on the lower level of the building to delay the demonstrators trying to break in, was coming now through the air vent into the vault. So we began to become overcome by it. About an hour had gone by, all the most sensitive documents had been destroyed, and we figured that we could hold out no longer and had to leave because it was just getting impossible with the tear gas.

“I remember looking back and there was this smoke coming from the embassy building. . . . we could hear people saying, ‘There they are! There they are!.’”

Fleeing the Embassy: Our embassy was part of an apartment complex. There was a courtyard and we walked through the courtyard, and while we were going across the courtyard the shutters of a window across the courtyard opened. There was this guy in uniform and he sits there leaning with his shoulders on the windowsill. Actually that guy just watched us going across the courtyard. It felt a bit chilling.

We went into the next building, where we had a storage room, and entered this storage apartment from the courtyard door. We said, OK everyone, we’re gonna go downstairs to the front door and go out in groups of two or three and then our plan was to walk casually about a mile to the British Embassy, because this entrance was around the corner now from our embassy entrance and we hoped that if we just walked out of the building in small groups, we might just blend in with the demonstrators if there were any there. At least, that was the plan.

We went down to the front door. I was in the lead. I opened that door onto the street and as I mentioned, it was around the corner from the embassy and there was the edge of the crowd. I closed the door and that was the one time I remember feeling scared.

And I closed the door and I said, “They’re out there, too!”

Bill Eagleton pushed me aside, opened the door, tore off and started running and he didn’t stop until he got to his residence, which was about a mile past the British embassy, about two miles away.

We started going out in groups of two or three, walking away. I remember looking back and there was this smoke coming from the embassy building and so forth. No one bothered us. Of course, we could hear people saying, “There they are! There they are!” But people on the edges of a crowd, they are more the onlookers. So they were trying to alert people in front but it was chaotic and no one paid attention. And we walked and we made it to the British Embassy and we were okay.

“My wife and two children thought for a few hours that I had been trapped in the burning embassy.”

The Aftermath: I believe that Gaddafi’s objective had been to take hostages so that he could emulate Khomeini. Whatever their goal was, it hadn’t panned out, probably because they had not counted on the embassy staff mounting effective resistance and they knew that we did not have Marine Security Guards at the embassy.

As I recall it the next day the remaining spouses and children were evacuated. My wife and two children thought for a few hours that I had been trapped in the burning embassy. From that day my daughter had for six months or a year a kind of an involuntary choking noise that she made and then it just went away. But it was a very scary time for them. I think they initially had believed that the worst had happened.

. . . [The embassy] was partly burned, but still usable. The internal gates and the tear gas had been pretty effective. The demonstrators carted away all the consular records, because they wanted to see which Libyans had been to the U.S. and who was applying for visas and so forth. They took out a lot of things but they didn’t get up to our second floor, which had the executive area, because with the internal gates, they just weren’t able to break through them before they were overcome by tear gas.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in International Service, American University 1965-1969

MA in International Studies, Columbia University 1969-1971

Joined the Foreign Service 1971

Dhahran, Saudi Arabia—Vice Consul 1972-1974

Damascus, Syria— Political Officer 1975-1977

Tripoli, Libya—Political Officer 1978-1980

Warsaw, Poland—Deputy Chief of Mission 1994-1997

Retirement January 1997