During the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, confidence in the Indonesian government plummeted. Foreign investment fled the country as the value of the rupiah fell to historic lows. Confronted with the loss of their bright futures, thousands of students poured out of the classroom to protest President Suharto’s crony capitalism. In the streets, rival factions of the army grappled for power. When military instigators screamed ethnic slurs into the crowd, tensions boiled over into a full blown riot against the “wealthy minority” population of Chinese-Indonesians.

Amid student protests and the destruction of Chinese-Indonesian communities, Suharto projected a façade of normalcy to the international community. After leaving the country for a non-essential meeting of the G-15, he returned only when armed forces shot and killed four protesting students at Trisakti University. Hundreds of Americans left Indonesia to escape the violence. Three days after Ambassador Roy ordered the evacuation of all non-essential personnel from the Jakarta embassy, the president’s cabinet refused to serve any longer, and Suharto stepped down. After being ousted, he enjoyed a comfortable retirement at home as his vice president B. J. Habibie acceded to the presidency.

During the crisis, Economic Officer Judith Fergin stayed behind in Indonesia—even after her husband and children were evacuated—to keep an eye on the pulse of the economy. Fergin began her Foreign Service career as a consular officer in Munich, Germany. She met her future husband on the first day of her second post in Pretoria, South Africa. Although Fergin came in as a political officer, she spent most of her career in the economic cone. Over the course of her career, she served in Indonesia, Russia, Australia, and Singapore. After serving as ambassador to Timor-Leste for three years, she retired in 2013.

Judith Fergin’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on September 14, 2018.

Read Judith Fergin’s full oral history HERE.

Drafted by Lydia Laramore

Excerpts:

“A whole generation of young people had not known anything but Suharto and rising tides for their entire life, and they were suddenly confronting the fact that life wasn’t going to continue to get better . . . .”

The Asian Financial Crisis: In Indonesia, confidence in Suharto’s ability to continue to lead the country was dwindling by the day. People had been willing to accept his autocratic rule when their and their children’s futures looked bright. But maybe that wasn’t going to be the case anymore. Compounding the “modern” economy’s travails and political tensions was the fact that Indonesia was in the grip of the worst drought in decades. As the factories closed in Jakarta and the workers went back to the countryside, the safety net that farming had always represented wasn’t there anymore. A whole generation of young people had not known anything but Suharto and rising tides for their entire life, and they were suddenly confronting the fact that life wasn’t going to continue to get better, that their aspirations, which were perfectly reasonable, were not going to be met. There was an enormous amount of unhappiness, distrust, and hardship.

“With some 10,000 students protesting at Trisakti University, the authorities opened fire and killed four students.”

Violence in the Streets: From the outset of the financial crisis, Suharto insisted in behaving as if everything was normal. So, in November 1997 he did his annual budget speech to parliament, which absolutely ignored the reality of what the exchange rate was, where interest rates were going, where foreign exchange earnings were going, all of that, and just basically it was the same old thing that he’d done year after year after year. This really rattled everybody, including the international community. In January of 1998, when IMF Managing Director Camdessus was there to witness the signing of the IMF program by Suharto himself, the scene was caught in a famous picture with Camdessus standing behind Suharto with his arms folded across his chest. It enraged Suharto and made it look as if the IMF was dictating to him, which didn’t play well. Actually, that wouldn’t have played well anywhere

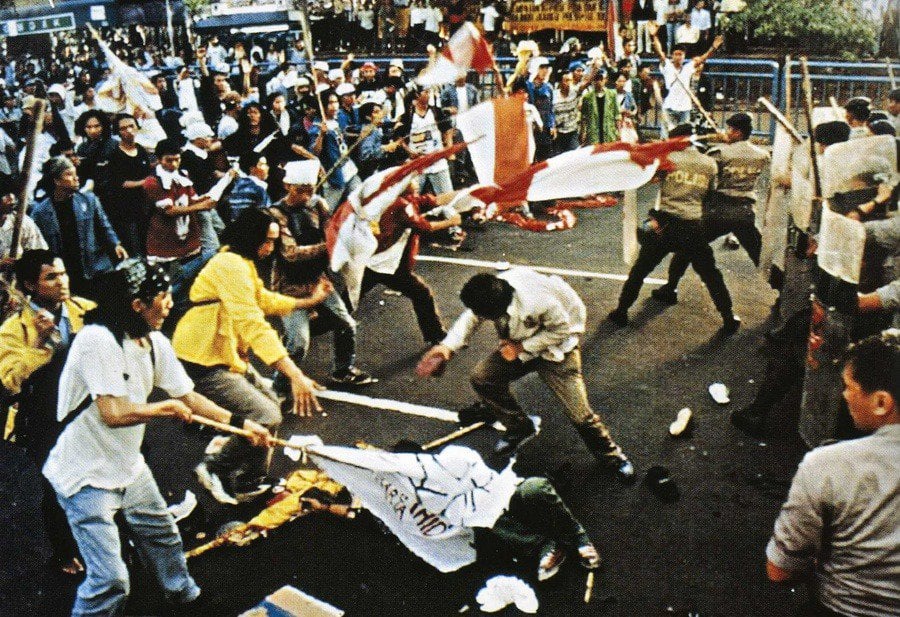

In the meantime, the international community was pressing the government to reduce fuel and other subsidies that were eating up the budget. The Indonesians resisted—there was a national feeling that, as an oil exporter, Indonesia should provide cheap fuel to its citizens. And then, in May of 1998, the government reduced the fuel subsidy. Protests began in Medan in northern Sumatra—it felt as if they were like a snowball, rolling down toward Jakarta, gaining momentum and size. In the middle of all this, Suharto decided he’d go off to Cairo for a relatively non-essential meeting of the G-15. Student protests had spread to Jakarta at this point—there were lots of plumes of black smoke as tires were burned. This was the early days of cellphones, so the students were able to communicate and organize. With some 10,000 students protesting at Trisakti University, the authorities opened fire and killed four students. Suharto cut his visit short, but by the time he got home events were pretty much out of control. The Chinese Indonesian population was particularly targeted—murder, rape, arson, and pillage, largely thought to be at the instigation of the military.

“Three days later, after Ginandjar led the ministers in declining to serve any longer, Suharto stepped down.”

Suharto steps down: On May 15, Ambassador Roy ordered the evacuation of non-essential personnel and, working with the Department, orchestrated the evacuation of hundreds of American citizens who wanted to leave. Three days later, after Ginandjar led the ministers in declining to serve any longer, Suharto stepped down and . . . much to everybody’s relief the constitutional procedures were followed and his vice president, B. J. Habibie, became the president.

It must have been the next morning the ambassador went to call on President Habibie, and he took me along to be the note taker, except for some reason I had to go in a separate car. So, I got to the palace on my own and the reception must have thought I was one of those pesky journalists and put me in a room by myself. In the meantime, the ambassador wanted a verbatim note taker for the message he was going to be delivering to President Habibie about the importance of democracy and pulling the country through this crisis and so forth. So, finally he got the message across that there must be somebody kicking their heels downstairs, and so I was able to come up and be the note taker for what I think must have been one of the most historic meetings I’d ever sat in. It was pretty exciting.

“We came home from the office one day and pulled in the driveway and looked up on top of our garage . . . to see a group of students — they were silhouetted against the sky on top of our garage.”

Student Unrest: A final very graphic memory was sometime in 1999 there was a lot of student unrest because Suharto wasn’t being charged with anything. But critics, especially university students, had found their voices and they thought that he should be charged with corruption, that his kids should be charged with corruption, and that the government ought to get on with this. There were a lot of students’ protests. We came home from the office one day and pulled in the driveway and looked up on top of our garage, which was flat-roofed, to see a group of students — they were silhouetted against the sky on top of our garage. They had been trying to get to Cendana to protest and in fleeing the authorities had rushed through people’s property and over their barbed wire fences. So we had a bunch of bleeding students, but only from barbed wire, not from being shot or anything, on our roof. So, for the first and only time in our careers we repaired to our safe room upstairs, which had all the locks and bars and doors you’d expect. We got the children in there, and then sat there wondering what next. Our steward, who may have only been in his 60s, but appeared to be in his 90s, was downstairs bandaging the cuts on the students’ legs and giving them drinks of water. If he could be out there doing that, what were we doing upstairs in the safe room? We emerged eventually just as the kids were leaving. Our steward talked them into just walking out the driveway instead of trying to get over the roof and down to the backyard and over the barbed wire to the next backyard—dramatic, but not necessary.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in Government, Smith College 1969-1973

MA in Soviet and Eastern European Studies, University of Virginia 1973-1977

Joined the Foreign Service 1977

Monrovia, Liberia—Economic Officer 1984–1986

Jarkarta, Indonesia—Economic Officer 1996-2001

Singapore—Deputy Chief of Mission 2004-2007

Timor-Leste—Ambassador 2010-2013