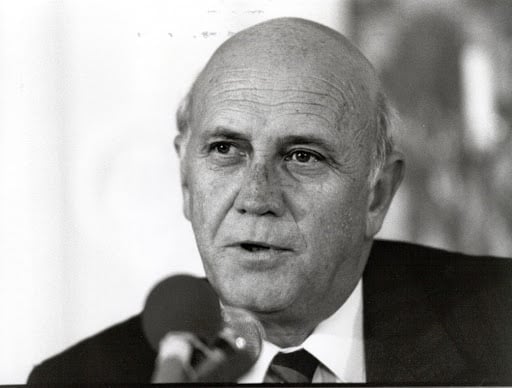

In a one-on-one meeting in 1989, the future president of South Africa, F.W. de Klerk, gave Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Herman J. “Hank” Cohen a preview of a plan that potentially would redefine the nation’s identity and help start it down the path of reconciliation. De Klerk promised that if elected he would end apartheid and free Nelson Mandela!

However, Hank Cohen would have to navigate several policy challenges in order to help steer U.S. foreign policy on South Africa towards achieving this plan. De Klerk was not yet elected, and it would be a six-month wait until the elections. To complicate matters, U.S. Congress was calling for more and tougher sanctions on South Africa. Cohen would have to keep de Klerk’s plan a secret and buy enough time to stave off more sanctions before the South African elections.

In 1989, the United States and South Africa had a contentious relationship. South Africa was punished with various economic sanctions as a result of its apartheid policies and the harsh treatment of its largely black population. Since 1949, the white Afrikaner minority had kept control of political power in the government through this systematic discrimination and segregation of non-whites. Apartheid’s ingrained racism and inequality brought social instability and violence. The South African government banned the African National Congress [ANC]—the largest black political party—to suppress black political power; Nelson Mandela’s subsequent arrest as a political prisoner further fueled internal dissent. South Africa became the target of frequent international criticism, economic sanctions, and arms bans, which pushed it into relative isolation from the international community for about forty years.

The aging regime of the white Afrikaners in the late 1980s signaled the need for a changing of the guard to a younger generation to carry on the legacy and power structure of South African apartheid. F.W. de Klerk won the election in 1989, became the successor to lead the country, and put his plan into motion. Assistant Secretary Cohen recalls in this “Moment” in U.S. diplomacy how he helped guide U.S. policy toward South Africa. He narrated the story in a “Tex Harris Tale of American Diplomacy.”

Herman J. Cohen’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on August 15, 1996.

Read Herman J. Cohen’s full oral history HERE.

Read more about Herman J. Cohen’s experience in his account for our Tales of American Diplomacy collection HERE.

Drafted by Ryan Jensen

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

“There was a tremendous bad feeling between the Congress and the Reagan administration over South Africa, and I want you to give very high priority to changing that.”

Tense Relations: There was a tremendous bad feeling between the Congress and the Reagan administration over South Africa, and I [James Baker who was Secretary of State under the H.W. Bush administration] want you to give very high priority to changing that.” The other thing was on the question of covert operations on Angola where he said we should find a way of getting out of that. “The rest,” he said, “I leave to you. I’m not going to get too involved in Africa.” So I had my marching orders, and I immediately started consulting with Congress on this issue.

What I found from people who were not ideologically involved either being pro South Africa regime because it was anticommunist, people like Senator Helms, or people who were on the opposite extreme, let’s nuke South Africa because of apartheid and all that. Very reasonable middle of the road members of Congress like Senator Borah and Senator Lugar, various Congressmen, Congressman Houghton for example, they said look we are all anti apartheid but we know it has to be a slow process. You can’t have a revolution there. We are against violence.

The big mistake the Reagan administration made was in not giving the Congress credit in their sanction legislation of 1986, not giving them credit for striking a blow against apartheid. They denounced Congress and this was a big mistake because we are all against apartheid, and the sanctions weren’t that bad. They were kind of mild. If the new Bush administration could show some gesture toward us as being anti-apartheid, you will get appreciation back. So I kept that in my mind and visited South Africa, but in 1989 some interesting things were happening on the ground in South Africa.

“Apartheid was something we believed in, but we know it is not going to work. He didn’t have a moralistic view, he had a very pragmatic view of the thing. He said we are going to change things. You will see.”

De Klerk’s Promise: The old generation of people in their 80’s who had really started apartheid in 1948, they were fading out. The President P.W. Botha was a sick man, and he couldn’t last much longer. There was a new generation of white Afrikaner leaders in their 50’s who were getting ready to take over. These people were much more enlightened and saw that for South Africa to prosper and continue to be a prosperous industrialized country, that the blacks had to be brought into the system. It wasn’t just a question of political rights. Africans had to become consumers and producers because they were the vast majority of the people. You can’t continue to run a modern economy on just 5,000,000 white people when you had 30,000,000 blacks who were not producing anything. So the idea was get them education, get them training, get them more participation in politics.

We saw that was happening, but our big problem was since it was a Democratic majority in the Congress, was to stave off increases of sanctions. There were some people who felt that South Africa hasn’t made any progress. Sanctions have made them think. Let’s get more sanctions to really topple that terrible regime. So, our problem was to walk a fine line between evolution in South Africa and what was happening in Congress. When we saw that F.W. de Klerk was going to be president of the country, this was in the middle of 1989 around August, James Baker said to me why don’t you go down there and interview this guy and see if he is for real. See if he is really going to make changes or is he just going to be the same old stuff but maybe with a pleasant face, something like that. So, I went down there.

They were in the middle of their election campaign where F.W. de Klerk was running for president. He received me for an hour. He interrupted his campaign. We had a one on one conversation and he told me very frankly that he grew up under apartheid, he made his career under apartheid, he had no apologies for apartheid, but as a new grandfather he saw that unless changes were made, there could be no future for his grandson. He said we have got to change. Apartheid was something we believed in, but we know it is not going to work. He didn’t have a moralistic view, he had a very pragmatic view of the thing. He said we are going to change things. You will see.

Debating De Klerk’s Promise: I went back and reported to Baker, and he said well what we have to do now is stave off the new sanctions. Let’s find a way to do that. Let’s work with Congress. So, I spoke to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee people. I said, remembering what I was told, that Congress wanted a little bit of credit. So they set up a hearing on the situation in South Africa, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. They said we are going to ask you what were the impact of sanctions. We are going to expect you to say that sanctions were helpful in this evolution that is taking place. We hope you are going to say that.

So this led up to a very big internal fight within the State Department because President Bush himself was opposed to sanctions. He didn’t believe in it as a way of making change in South Africa. So, I said we are going to get this question. What are we going to say? I proposed language which was the main economic impact of sanctions has hurt the black more than the whites because they have had more unemployment as a result. They have lost income and what have you. However, sanctions have had a strong psychological impact on the white ruling structure, and because of that, one of the reasons for that is that they are now changing. They are making profound changes and we are expecting fairly good things to happen we hope.

“Senator, let’s give it another six months. If within six months there has been no real positive change, let’s take another look at more sanctions.”

Convincing Congress: Now we knew that the left wing would not agree with that, but it might buy us some time. There was a big fight. People in the White House didn’t want to say anything good about sanctions, they didn’t want to make any concessions, but finally James Baker convinced everyone that my language was acceptable. We weren’t saying sanctions were the greatest; we are just saying it contributed to a change in mentality. So the question was asked in the hearing, and it was fully attended. Every member of the Foreign Relations Committee was there which is unusual for an African issue. Usually there are two Senators, something like that. They were all there and the question was asked, and I gave this answer which had been worked out in advance. Senator Simon of Illinois got very happy. He was Chairman of the Africa subcommittee at the time. He actually was chairing the hearing. He said I am very pleased to hear that, and that is very good, and I hope we will continue working together.

But, Senator Sarbanes of Maryland who was part of the very rabid anti-apartheid side the liberal left, being a very crafty lawyer. He said, “Mr. Cohen, that is a very interesting answer but if you say that the sanctions which were imposed in 1986 which were of a rather limited nature had a very important impact, don’t you think that more sanctions will have more of an impact and really push this apartheid regime out? You say good things are happening, but when do you think we should look at this again at some point?” I had known from our intelligence information and other sources that de Klerk if he got elected, that he was going to be releasing Mandela sometime in the first quarter of 1990 and legalize all political parties including the ANC [African National Congress] and the Communist Party. I said, and this was October, “Senator, let’s give it another six months. If within six months there has been no real positive change, let’s take another look at more sanctions.”

The Reaction and Aftermath in South Africa: This caused a tremendous uproar in South Africa. The press was full of statements from the government—we don’t accept deadlines from the United States. They can’t impose any deadlines on us. We resent this tremendously. But, in the State Department they were saying great work, Hank, you have bought us some time because otherwise we could have had more sanctions now. So I said, “Well it is up to the South Africans. We are giving them six months, and if they do all the right things, then the whole issue will fade away.” So, this is exactly what happened.

De Klerk got elected in September; he took office, I think, in December. The new parliament met in late January. When the new Parliament met, he announced his changes. All political parties are now legalized including the African National Congress and the Communist Party of South Africa. He hinted that he would release Mandela, although he didn’t give a date. Our diplomacy changed from one of putting pressure on them to change the system to working with them to see how they can have a smooth transition.

TABLE OF CONTENT HIGHLIGHTS:

Education

BA in Political Science from City College of New York 1949–1953

MA in International Relations from American University 1962

Joined the Foreign Service in 1955

France—Political Counselor 1974–1977

Senegal—Ambassador 1977–1980

National Security Council—Africa Advisor 1987–1989

State Department—Assistant Secretary for African Affairs 1989–1993