While U.S. State Department employees regularly serve in the midst of pivotal international agreements and turmoil, the events going on surrounding their personal lives are often equally fascinating. Social change, and in some cases rebellion, characterized the formative years of many senior U.S. diplomats.

From the 1963 March on Washington to the Bureau of Indian Affairs take-over in 1972, this era was packed with previously unheard voices. While such voices did eventually affect change even in the venerable institution of the State Department, their currents were not unfelt by young up-and-coming members of the time.

Attending school at Texas A&M and Berkeley in the late 60s, USAID officer Craig Buck experienced first-hand the ripples caused by these events. With fears of being drafted to Vietnam shadowing thoughts of graduation, and notable political assassinations dominating the news, caprice and uncertainty were the themes of the time. Keep reading to find out about Craig Buck’s brushes with South American rebels, affiliation with Bobby Kennedy’s campaign, and other social stirrings.

Craig Buck’s interview was conducted by Mark Tauber on August 3, 2017.

Read Craig Buck’s full oral history HERE.

For more Moments on social movements, click HERE.

Drafted by Aaron Derner

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

“I was reprimanded in speech class by a teacher for arguing that schools should be integrated, as well as abolishing the death penalty.”

Early Brushes with Social Injustice:

BUCK: Carthage basically operated under Jim Crow principles: Blacks lived in one section of town. There was no social interaction. The restaurants were segregated. Water fountains were segregated. Schools and churches were completely segregated by race. It was interesting, because I had grown up in a family that did not – I just had no interracial experience and certainly was never taught to practice or even understand this sort of thing.

One summer during grade school I went on vacation with a friend and his family. Before we went I had had it beaten into my head at school and by others in east Texas that you were supposed to say “sir”, or “ma’am” to people older than me, which I had never done before. But, so fine, I learned to do that. Then, I was with my friend on this summer vacation, and a black was helping us do something, and I said, “Yes sir,” and, “No, ma’am,” and the guy’s father pulled me over and was very stern with me.

He said, “You do not ever say ‘sir’ to a black.” So, at that point, I’m kind of like – You know, I was 10 or 11 years old, trying to figure out why. So, my first awakening to social issues. But, you saw it all the time if you began to look, and I began to do so and I was not pleased with what I saw around me. I think my mother had quite an influence in terms of learning that “This is an unacceptable practice.”

Q: Now, Carthage High School was also segregated?

BUCK: Yes. It didn’t desegregate until long after I graduated in ’62. It probably was another eight or ten years, at least, before it desegregated. Open discussion in school of Brown vs. Board of Education and what it meant and how it would be accommodated was quickly shot down. I was reprimanded in speech class by a teacher for arguing that schools should be integrated (as well as abolishing the death penalty).

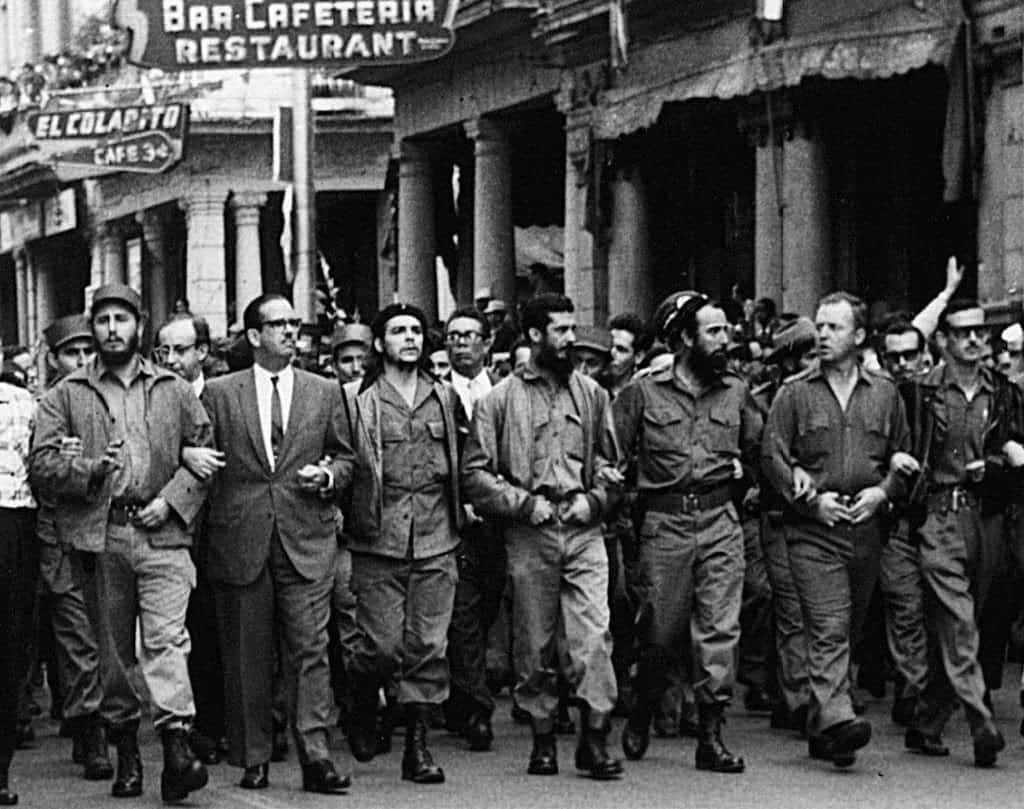

“Neither I nor my university friends and other contacts knew that it was Che Guevara, or that it was a significant guerrilla movement at that point.”

Revolutionary Change Abroad:

BUCK: I postponed college in the United States and took the Fulbright, postponed the Woodrow Wilson gift, and went to Bolivia for a year. I actually stayed down there for almost a year and a half.

Q: Okay. How did you choose Bolivia? Or was that the country on offer?

BUCK: Well, I had become quite interested in the politics of agrarian reform, labor unions, the relationship of these groups to political parties, and Bolivia. At that time many of the Latin American countries, South American countries, and Central America, were ruled by these dominant elites—latifundistas (owners of large estates who often employed people who lived on their land as serfs or nominally paid laborers) and what have you. Bolivia had undergone a wrenching economic and social revolution in 1952, so I found that rather fascinating, and the fact that so few people knew anything about Bolivia. It seemed to be isolated, off the radar, and it just seemed like a great place to go. I was very pleased that I chose Bolivia.

…

Q: And that was when Che Guevara was there?

BUCK: That’s correct, yes. It was fascinating because I was in Cochabamba, Bolivia, and we learned from the media that there was a guerilla movement against the government. It was several hundred miles away in the Orient, or the eastern mountain ranges between the high altiplano and the eastern jungles. Neither I nor my university friends and other contacts knew that it was Che Guevara, or that it was a significant guerrilla movement at that point. I travelled all around the country, by hitchhiking, by bus, you name it and I wanted to get down there and see what was happening with my own eyes. By chance, – Well, I was quite close with the consulate there because they paid my nominal stipend.

One evening, just after learning of the guerilla group, I happened to be at a social occasion organized by the U.S. consulate and I mentioned to the consul general that I was leaving the next day for the eastern mountains to see what was with this guerrilla movement. And the consul general said, “Come in and see me tomorrow before you go, please.”

So, I went in, and he said, “Craig, under no circumstances are you to go there.” Fortunately, I took his advice, because God knows what may have happened had I ended up down there just as a student.

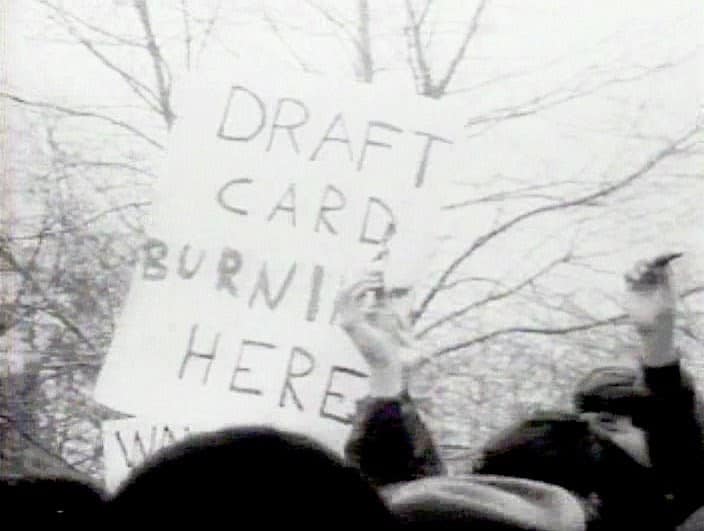

“At school we had sit-ins, teach-ins, the occupation of the main school administration offices, the burning of the ROTC building, the ejection of ROTC from campus, Berkeley draft riots just across the Bay, draft card burnings by the dozen, the end of the summer of love. And for comic relief we had a topless dancer and a Libertarian vie for Stanford student body heads in the same position that David Harris had held a couple of years earlier.”

Assassinations and Domestic Rebellion:

Q: So, with all of the uprisings in the U.S., and the assassinations, it was a big year. And of course, by continuing on a path of study and being a full-time student, you would continue to be able to use your status to avoid the draft.

BUCK: That’s right. It was really funny; while I was still in Bolivia in 1967, I happened to get a letter by mail from my draft board, saying that since I had graduated from college that I had been reclassified 1-A [the category meaning I was eligible for the draft and would be immediately inducted], and to please report for my physical. Oh my God, I was crestfallen. I wrote them a letter back, noting that I was in Bolivia doing graduate work, and they responded with the equivalent of, “Oh, thank you very much for advising us. We’ve got other cannon fodder and we reinstate your student deferment.”

But, I was quite concerned about my draft status, because this was indeed right in the middle of the war. While at Stanford I had been working for the election of, I guess it was at that point Eugene McCarthy. Clean Gene. But, just about six weeks before Robert Kennedy was assassinated, one of my professors said, “That’s great, Craig, and I think that his ideas are great, but he doesn’t have a chance of winning the election. Bobby Kennedy will win the election if he’s nominated.” This was my most respected professor’s opinion, and I had to agree. So, I changed, started working for Bobby, and then of course you know what happened six weeks later.

…

Q: So, let’s continue then from 1968. Did the events of that year affect you?

BUCK: Oh, very much so. The assassination of Martin Luther King, Johnson’s decision not to run for reelection, Bobby Kennedy’s assassination, Watts and Washington D.C. burning, the Vietnam war expanding and continuing to go on. At school we had sit-ins, teach-ins, the occupation of the main school administration offices, the burning of the ROTC building, the ejection of ROTC from campus, Berkeley draft riots just across the Bay, draft card burnings by the dozen, the end of the summer of love. And for comic relief we had a topless dancer and a Libertarian vie for Stanford student body heads in the same position that David Harris had held a couple of years earlier. As Bob Dylan said, “The times they are a-changin.”

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in Government, Texas A&M 1962–1966

Fullbright Scholar, Universidad Mayor de San Simon 1966-1967

Woodrow Wilson Scholar, Stanford 1968-1969

MA in Economics, Stanford University 1979–1980

Joined USAID 1969

Kampala, Uganda—Acting Mission Director 1980–1983

Lima, Peru—Mission Director 1989–1992

Almaty, Kazakhstan—Head of Central Asian Programs 1993–1995

Sarajevo, Bosnia—Mission Director 1995–1999