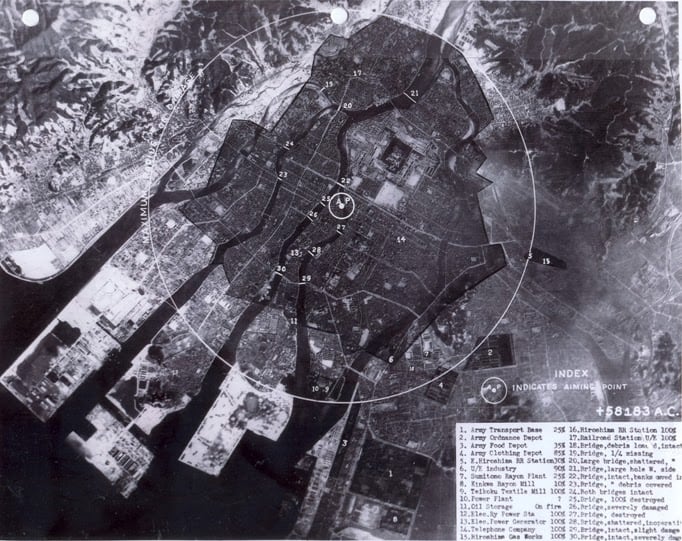

One of the most defining moments of the twentieth century was the detonation of an atomic bomb over the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Not only did it hasten the end of the Second World War, but also ushered in a new era for international conflict, fraught with uncertainty and the recognition of a latent rivalry between two superpowers.

However, for many of us, this shift in history is not particularly personal—we hear about these events long after their occurrence, which differs from the perspective gained through living during their unfolding.

Edward L. Rowny was a lieutenant general who served in World War II and witnessed firsthand the changes that the atomic era brought in. He was involved in planning the invasion of Japan that never happened, and he worked to restructure the military to meet the demands of the developing Cold War. He experienced the effect that a weapon of mass destruction had on war planning; particularly the strategy of its use and how to respond militarily in the event of a nuclear attack. If already the future seemed uncertain with the drastic increase in the magnitude of warfare, it was compounded by the realization of an emerging ideological struggle. Rowny also witnessed the rising salience of the Soviet Union and its designation as the United States’ foremost enemy.

In this “moment,” Rowny discusses the implications of the close of World War II and the deliberation over the use of nuclear weapons as well as the response to the USSR. His experience communicates the uncertainty of the time free from the benefit of hindsight.

Edward L. Rowny’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on July 2, 2000

Read Edward L. Rowny’s full oral history HERE

Drafted by Wilton Cappel

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“We formed our ideas early on that the Soviet Union was on the march ideologically and was not going to cooperate with the West.”

On the Soviet Union as a potential enemy: We had all these signals coming in as to what was going to be the future of our relationship with the rest of the world and, particularly, with the Soviet Union. There was the idea of the Soviets allowing elections in Poland. However, they put in their own puppet so that the Poles in London had a government in exile. That played into all this, so the Soviet Union was very much a pariah….

We had the cables back from General Dean who was the head of our Lend-Lease; he later put these into a book called Strange Alliance, which is my number one book on negotiating with the Soviets. He told about how difficult they were to deal with. Even though we were giving them Jeeps and ammunition and all kinds of other equipment, they were making life difficult for us. For example, when U.S. pilots were shot down over Poland or Eastern Europe, the Soviets put these pilots into prison camps. They were only released after the war. It was outrageous….

We formed our ideas early on that the Soviet Union was on the march ideologically and was not going to cooperate with the West. They were more interested in promoting their ideology than in moving on with the occupation policy.

Post-Atomic Policy: As far as the atom bomb was concerned, you called it the major influence in Washington at that time. This came from [International Relations Theorist] Morgenthau who was very much in favor of using the atom bomb in any tense situation. It was later our plan to make a new war department, and Washington’s idea was to use the atom bomb only if our national survival was actually at stake….

There were great debates within the academic community at Yale about which way U.S. policy should go on the atom bomb but Bernard Brodie won out in the end with his book….

The thrust of this book was that we would not rely on atomic weapons in ordinary situations, that it was the ultimate arbitrator and that it would prove strategic bombing to be a success. There was some controversy about strategic bombing and surveys were made about how much damage the regular bombing campaigns had done. Now, this was the absolute weapon, and it was to be used only in the extreme case of national survival being at stake….

It was very difficult to deal with and especially in a charged atmosphere of the newly formed Air Force, which would take over and control this weapon. There was a great deal of anxiety about how all this would work out. I think with this charged atmosphere in the Pentagon and preoccupation with redesigning the new forces and with the occupation problems facing us, it took an outside agency, like academia, to lead the way on thinking.

Potential Nuclear War: The feeling was that we had to negotiate with the Soviets quite carefully. We had to be careful because of their strong ground superiority. They were now becoming superior in numbers of strategic weapons. As a result, we were quite apprehensive. We always felt we would be able to absorb the first nuclear blow and have enough weapons left to completely obliterate the Soviet Union. We were quite confident that if they ever started a war we would be the ultimate winners. Nevertheless, we didn’t relish the idea of ever getting into a nuclear war….

If we lost a million or two at Washington and New York, the question was, would we have the heart to continue to fight and sacrifice even more people or would we sue for peace? Our thought was to try to play down any of these calculations, “Well, we’ll take 10 million casualties and take 20 million casualties.” We all thought that was taking a negative approach. Our objective was to be sure that a nuclear war would never occur. We could not allow the Soviets to believe we would succumb to their threats without a fight or, nor could we permit them to feel that in any situation they would employ nuclear weapons. If it came to that, the game was over.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BS in Engineering, Johns Hopkins University 1933–1937

West Point 1937–1941

Military Service

Pentagon—Operations Department 1945

Tokyo, Japan—Far Eastern Command 1949

Strategic Arms Limitation Talks 1973–1979