At the beginning of the 1960s, U.S. foreign policy had two bugbears: the Soviet Union and Cuba. Fidel Castro had come to power in 1959, and the United States wished to prevent another Cuban Revolution with policies like the Alliance for Progress, designed to forestall revolutionary tendencies by encouraging moderate reforms.

But the United States was nonetheless worried about potential leftist revolutions springing up across the region. That certainly played out in Ecuador.

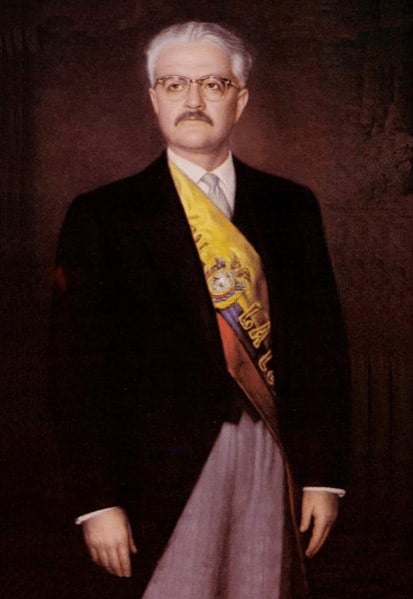

When Ambassador Maurice Bernbaum arrived in the country to replace the previous appointee (who had died four days into the job), perennial president Jose María Velasco Ibarra was in office. However, the military soon deposed him, and Ecuador elected his vice president, Carlos Arosemena, the new president. However, as Bernbaum soon found out, Arosemena, a committed leftist, did not always support U.S. policies or interests. Matters came to a head when Arosemena drunkenly insulted the United States at a banquet, an event the military used as an excuse to overthrow Arosemena.

Bernbaum, who had previously served as Deputy Chief of Mission in Ecuador, continued as Ambassador to Ecuador until 1965. He subsequently became Ambassador to Venezuela until 1969, when he retired.

Maurice Bernbaum was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy on January 13, 1988.

Read Maurice Bernbaum’s full oral history HERE.

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“They were always a bit suspicious of our motives; they never could quite believe that we didn’t want to get some political advantage out of it. I always tried to assure them that wasn’t so.”

The Alliance for Progress: Well, very early in my period there we had the Alliance for Progress. Our prime interest was to further the Alliance for Progress in Ecuador—to get them to accept our assistance and make use of it. We had a problem there. The Ecuadorian government, of course, was very much interested in whatever assistance we could give them. They were always a bit suspicious of our motives; they never could quite believe that we didn’t want to get some political advantage out of it. I always tried to assure them that wasn’t so. But one of their big problems was that they had most of their revenues earmarked for autonomous agencies. It was very difficult then for the government to furnish its share of the projects which were being financed under the Alliance for Progress. That was one of the problems that I had all the time. I used to travel around the country pushing for collaboration. I used to spend a lot of time with [Arosemena], who was not very pro-American. He had had problems when he was in the Embassy in Washington.

Q: How effective was [the Alliance for Progress] in Ecuador, and what form did it take?

BERNBAUM: Well, intensified training and the granting of loans to do the job that we thought should be done in the country and that they wanted. The main obstacle to that was what I described before. The inability of the Ecuadorian government to furnish its part of the cost. We were asking them to furnish only about 20% of the cost of these projects, and we were extending loans on the basis of no interest for ten years, and in fact were gifts. I do think that a lot of good had been done, but eventually it deteriorated.

“He always wanted to stick needles in people when drunk. We used to have some conversations about that.”

Arosemena’s Drinking Problem: [Arosemena] was a really complicated individual. His father had been president of Ecuador. He came from one of the first families in Guayaquil. He was more or less a maverick in his community. He was addicted to drinking. He was a dipsomaniac. And somehow or other he always seemed to be interested in stirring things up. I remember one time as vice president when he insulted the Chinese ambassador, he was a bit drunk at the time. And another time when he insulted the Colombian ambassador. He always wanted to stick needles in people when drunk. We used to have some conversations about that. His problem was that he couldn’t stay away from the bottle, and that made life with him somewhat difficult. …

President Kennedy had made an imprudent comment to Arosemena’s brother that he might invite the Ecuadorian president to visit the United States. When I heard about it, I wrote to oppose the invitation because of Arosemena’s dipsomania and corresponding unpredictability. So the invitation was held off for quite a long time. Finally the Ecuadorian president let it be known that he was awaiting an invitation.

“I said, ‘Mr. President, you did a terrible thing. I was about to win that tournament, and you pulled me off the golf course.’ He said, ‘In a good cause.’ He said, ‘I’m being pressured by the military to break relations with Cuba. What do you think about it?’”

Discussions on Cuba: [Arosemena] was under pressure from the military to break with Cuba, and he didn’t want to break with Cuba. I’ll always remember this, I can tell it now.

I was playing golf one Saturday, and his aide came along to say that the president wanted to speak with me. And so I left the course. This was always a topic of conversation between us. He was always kidding me about playing golf. And I said, “Mr. President, you did a terrible thing. I was about to win that tournament, and you pulled me off the golf course.”

He said, “In a good cause.” He said, “I’m being pressured by the military to break relations with Cuba. What do you think about it?”

I said, “That’s your baby, not mine.” And he tried in every which way to get me, to commit me, to tell him what to do, and I wasn’t going to do that. And finally he said, “I’m wondering whether I shouldn’t have a plebiscite in the country on that subject. What do you think about it?”

I said, “I will then express an opinion. You’d just divide the country. It seems to me that would be silly. In that case I’d suggest it would be far better not to break, then to have a Plebiscite.”

That ended the conversation. Later that evening the Minister of the Interior visited the embassy to tell me that the President had broken with Cuba.

Q: Well, what was he trying to do? To get you to commit yourself and then to say . . ?

BERNBAUM: He was probably trying to be able to say that he was forced by the U.S. to break.

Q: Well, at that time it was our policy, wasn’t it, was it at Punta del Este or someplace? Wasn’t this our policy to try to have the South American countries break with Cuba?

BERNBAUM: Oh sure. But the question was, how do you do it. We had Adlai Stevenson visiting. He made a swing around Latin America shortly after Kennedy was elected. One of his purposes was to convince the various governments to break. I remember a conversation we had with President Velasco Ibarra, who was not at all sympathetic. He thought we were a country of cultural barbarians. He was more or less a Francophile, and an Americanphobe. But he did respect Adlai Stevenson, who was one American he thought was a really fine individual. Every time Stevenson would make a point, the old man would rebut him by saying, “Well, governor, on page so and so of the book you wrote, you said something to the contrary.” Or, “You made a speech on a given date where you said something to the contrary.” And finally Stevenson had to give up. But aside from that, we never expressed an opinion to the government about what they should do.

“Then he turned to one of his ministers at the other side of the table, and said, ‘Paco, you agree with me, don’t you?’ Well, this minister at that point was studying the molding on the ceiling. Finally he said, ‘No, Senor President.’”

The Fateful Banquet: Arosemena had been involved in various incidents due to drunkenness. One of them was when he met the Chilean president at the airport in Guayaquil and was drunk. It was said that if it hadn’t been Christmas he would have been overthrown then.

Later, Admiral McNeil, president of the Grace Line, visited Ecuador with his wife. The president gave a banquet for them, because the Grace Line had participated in the inauguration of a new vessel. The president’s wife had been invited to visit the United States.

His apartment was above the presidential office, so I showed up there, where I expected the party to take place. He was there with a few of his ministers, including the Foreign Minister. He was already half gone. As I walked in he said, “Ambassador, have a drink.” I said, “Well, Mr. President, let’s go downstairs, we’ll have the drinks down there.”

We got him down there, and he made a speech decorating the admiral. He neglected to mention my presence. Whenever he was annoyed with the U.S. for one reason or other, he’d neglect to recognize my presence. So I knew something was up.

During the soup course at dinner, he arose—by that time he was really pretty much under the influence of liquor—and made a long rambling speech in which he attacked the U.S. government for exploiting Ecuador without mercy. Well, of course, you can imagine the reaction at the table.

He turned to me and said, “You agree with me, don’t you, Mr. Ambassador?”

I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry, so I said, “No, Mr. President. When you’re speaking of the government, you’re speaking of the American people.” He had spoken highly of the American people as being distinct from the government.

Then he turned to one of his ministers at the other side of the table, and said, “Paco, you agree with me, don’t you?” Well, this minister at that point was studying the molding on the ceiling. Finally he said, “No, Señor President.”

Arosemena got up, and staggered out of the dining room. Dinner continued, and finally we finished. The various ministers came along and said, “You’re not going to make anything of this, are you?”

And I said, “No, under those conditions. I don’t know what brought it on, but I’m sure he wouldn’t have done it if he was sober.” I remember it was a sub-secretary of Foreign Affairs who came along and said, “It makes no difference what you say.” He said, “The three chiefs of the armed forces who were at that dinner have just decided that this is it. This man’s gone too far.” And they just threw him out of power.

“He said, ‘Well, we decided that we just had to oust him.’ He said, ‘If we hadn’t done it, the ranks would have done it.’”

The Aftermath: Well, what happened the following day was that we were giving a farewell luncheon for our Armed Services attaché, and one of the members of the newly appointed junta, Colonel Gandara, came over to bring his wife. This is quite a coincidence, but it was interpreted by virtually everybody as indicating that we were in on the overthrow.

I asked Gandara at the time, “What’s going on?”

He said, “Well, we decided that we just had to oust him.” He said, “If we hadn’t done it, the ranks would have done it.” And then he left. Arosemena was flown to Panama.

I reported the incident to the State Department, and it was reported quite accurately in Time Magazine.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BS, Harvard University 1927-1931

Joined the Foreign Service 1936

Buenos Aires, Argentina—Deputy Chief of Mission 1959–1960

Quito, Ecuador—Ambassador 1960–1965

Caracas, Venezuela—Ambassador 1965–1969