E Pluribus Unum. The average American will unwittingly encounter these very words on a daily basis and hardly give them a second thought. But this is not some meaningless Latin phrase that we simply plaster all over our currency for no reason. In fact, it provides an exemplary representation of the American democratic ideal: an empowerment of the masses—regardless of racial, social, or religious background—and their voices in shaping a unified American identity.

One may even go a step further and claim that these words additionally represent an American perspective of a global democratic ideal; a brief analysis of U.S. foreign policy in recent decades may testify to the fact that we have sought to promote similar values of democracy throughout the international sphere.

Robin Angela Smith has devoted much of her career in the Foreign Service to the pursuit of this broader aspiration for global democracy. Her efforts in Haiti to emphasize Martin Luther King’s concept of non-violence inspired adolescents to contribute their own thoughts on the topic during a time of much political tension. She maintained her determination to this cause during her tour in Mozambique, where her organization of election night events allowed its populace to see the intricacies of American politics, all while having a laugh in the process. And finally, regardless of their ultimate outcome, her activities in Iraq sought to assure the Iraqi people that the U.S. would aid in their establishment of a “democratic, unified, and multiethnic” country.

Smith’s commitment to public diplomacy has additionally manifested in other notable ways, whether it be through implementing policies in Washington, D.C. with the Africa Bureau for Public Diplomacy or promoting opportunities for women in Kabul. Smith retired in 2017, and she is currently mentoring a freshman at Georgetown University, as she firmly believes that mentorship and guidance is the key to future successes in the Foreign Service.

During a 2009 press conference, former President Barack Obama remarked: “The strongest democracies flourish from frequent and lively debate, but they endure when people of every background and belief find a way to set aside smaller differences in service of a greater purpose.” These words, as well as Robin Smith’s example, remind us that no matter the difficulties we may face along the way, we should learn to embrace all members of our societies to achieve a truly sustainable model of democracy at the national and international level. Let us bridge our societal divides. Let us hear the people sing.

Robin Angela Smith’s interview was conducted by Mark Tauber on February 6, 2019.

Read Robin Angela Smith’s full oral history HERE.

Drafted by: Will Shao

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“I remember the embassy security officer said that he’d drive around in the evenings and see Haitian kids sitting on street corners under street lamps working on their nonviolence essays.”

Empowering the voice: One highlight was a series of events I organized in honor of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., because I thought that an observance of Dr. King would speak to issues of non-violence, inclusion, and a democratic process – topics of importance for all Haitians to hear at that time. One key cultural event I launched was attended by President Aristide, the political establishment in Haiti (including opposition members), and the U.S. ambassador. You have to understand that the event was so moving given that it was a call for unity by various Haitian groups and individuals during a time of much tension. My supervisor, the PAO, told me that the President and the ambassador had even shed tears, but I didn’t notice as I was working the event. I was worried about rather mundane things, such as if we would have power, because this event occurred when the economic embargo was in place and electricity was sporadic.

I also visited the King Center in Atlanta during this tenure, which led to its recommendation of experts trained in Kingian nonviolence as event speakers. That’s how I was able to organize several events in Port-au-Prince and even once in Cap-Haitien with different King Center affiliates. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) was also supportive of my efforts, and in fact helped defray costs of one or more of my Kingian programs. I must add that I had an excellent and cooperative relationship with USAID both in Haiti and throughout my career with regards to some of my outreach, education and speaking events.

Indeed, for my programming efforts in Haiti on the topic of Kingian nonviolence, I received a meritorious honor award. The recognition was for extraordinary devotion to duty in promoting democratic efforts under adverse conditions through the imaginative conception of multiple programs in honor of Martin Luther King Jr. – this initiative received an unmatched degree of success in comparison to similar efforts launched by other countries in Haiti, according to some observers.

Another impactful initiative was an essay contest on the subject of nonviolence. It was part of a six-month educational effort that I conceived to promote democratic debate and civic awareness among young adults.

Q: In French or in Creole?

SMITH: Oh, in French. It was significant because the topic resonated with society during this tense period, especially among the youth; the contest stimulated interest among Haitian youth in Dr. King’s philosophy. I remember the embassy security officer said that he’d drive around in the evenings and see Haitian kids sitting on street corners under street lamps working on their nonviolence essays. They probably didn’t have power at home, but were still so motivated to write and be heard. We had a committee that chose the top ten best essays, fundraised, and sent these kids to the King Center in Atlanta for training in nonviolence. What a wonderful experience for the young, talented selectees! After the contest ended, MLK clubs were established among secondary school students to continue scholarly pursuit, with media reporting amplifying its reach. Based on my success in organizing the essay contest, I was contacted by the combined United Nations / Organization of American States civil mission in Haiti for advice on their efforts to launch a similar contest.

“Before I arrived, I knew I wanted to do something big and impactful.”

Bridging the Divide: Now, what was the general timbre of the media towards the U.S. that you had to deal with at that time?

SMITH: You have to understand that the country was a socialist state with close ties to East Germany and the communist bloc. There was still a lot of residual resentment towards the former colonial power Portugal and our support for the Portuguese, until the Lusaka Accords resulted in Mozambique’s independence in 1975. It was in this geo-political environment that many journalists and their editors were schooled, although the younger press didn’t carry as much baggage. As a result, at times, it was still a struggle to get good credit or coverage of the significant assistance that we were able to do in the country, in part because of this history.

Q: Right. Were there many Mozambicans who went to Brazil or Portugal?

SMITH: There were, of course, among those who had the means.

Q: Ah, I see.

SMITH: As for my responsibilities there, one activity I did was highlight the importance of free and fair elections. In this regard, I organized an election night event. Many missions do likewise. But, as you know, this was quite an interesting election: Bush versus Gore.

Before I arrived, I knew I wanted to do something big and impactful. I also knew that organizing an election night event takes a lot of advance planning because, first of all, you’ve got to order supplies and line up speakers. One thing I did that stood out from other election night events, certainly in Africa I was told, was that I had organized simultaneous observances in two cities: Maputo and Beira, the two most important ones in Mozambique. Located in the central portion of the country, Beira was especially influential with the political opposition. So, I felt it was important to have election watch events in those two locations, and was hoping that we could pull it off, which we did. I sent my one American assistant to oversee election night activities in Beira with the help of our Fulbrighter. We had our own event in Maputo with a military band, mock voting, materials, and an electronic dialogue with Voice of America (VOA). We invited a large gathering – press, politicians, civil society and journalists. The government sent its official representative. The entire mission was involved.

Q: Because there’s a six-hour time difference . . .

SMITH: Yes, there was a time difference, which meant that the election watch was a late-night event extending into the early morning. It was wonderful. Leading up to the event I aired several of the presidential debates. We concluded one with a comedic sketch from “Saturday Night Live,” a very illustrative example of how we can poke fun at our politicians without dire consequences. Another example of democracy in practice was the outcome of that year’s presidential election. Mozambicans, and the world for that matter, saw Gore win the popular vote, but concede to Bush in a highly contested election that could have turned ugly. I believe it left a lasting impression, because there were two polarized groups in Mozambique which only recently had worked out their differences peacefully.

Q: Did most people who were watching understand what the issues were? Had you had time to brief them on what the two candidates were talking about?

SMITH: Yes, we had our information outreach efforts – WorldNet interactives, VOA programs, speakers, debate watch events, and press engagements. We may have even sent a participant to Washington under the auspices of the International Visitors exchange program focused on U.S. elections.

“This was a decisive time in our relationship with Iraq. Decisions we made shortly after the toppling of Baghdad had long-term repercussions, as many critics have noted.”

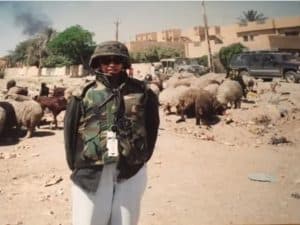

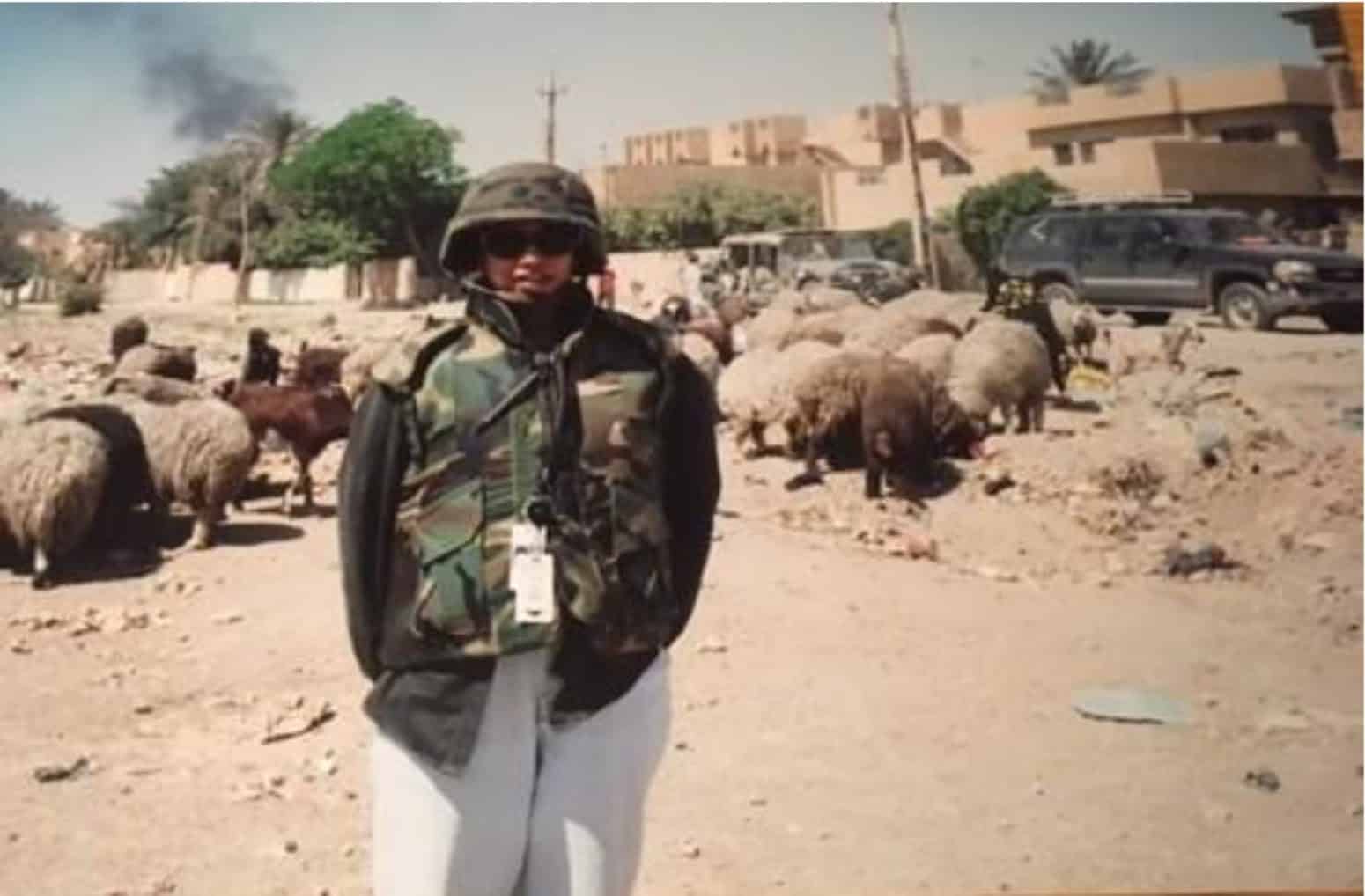

An Unresolved Tragedy: I was part of the planning process for the establishment of Baghdad’s coalition information press operation. Only two of us – Foreign Service officers from State – were detailed to Baghdad to help staff the press center. Our job was to highlight CPA and the administration’s overall mission. We were set up in a huge cavernous room with a staff of 40-plus civilian and military personnel, including representatives from coalition countries. I felt thoroughly integrated with the team, working side by side with colonels and junior members who often sought my advice on work-related issues.

Q: And what was the mission?

SMITH: Helping the Iraqi people build an Iraq that is democratic, unified, and multiethnic.

Q: What were your roles and responsibilities?

SMITH: I was part of the press support effort from the outset of our operations in Baghdad. We started with limited equipment and material resources, but had to service over 200 press outlets operating in Iraq just weeks after combat operations ended. Our job was to get out positive messages about our efforts in the country. As our telecoms improved, we were able to better serve the large U.S., international, and Iraqi press contingent.

I also served as a public affairs point person for the Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Affairs (ORHA), which had a major pillar focusing on humanitarian assistance. Much of my time was spent organizing press interviews and media opportunities for members of the humanitarian assistance team to make known to the Iraqi people and foreign audiences our positive record on humanitarian demining, human rights and food delivery. That’s when I encountered the Mozambican demining team on an organized press opportunity highlighting ORHA efforts. I also assisted other press officers with media events related to ORHA’s other two pillars: reconstruction and civil administration.

Shortly after I arrived, I was also tasked with the important job of providing a daily media report to the senior leadership. It was essentially a compilation of media reports, which had me working late evening hours after securing a computer that wasn’t in use as I didn’t have my own personal laptop. Another difficulty was slow internet in the first weeks of operation. I remember moving from room to room seeking different computers and better service. Meanwhile, we were using satellite phones to communicate with our offices at State and the White House until the military was able to install a dedicated line in our office.

Q: And how was travel? Or did you travel?

SMITH: Yes, but I have to add that movement was difficult in a high threat environment where shootings and firefights took place daily. We had to request force protection and faced high demand for the limited number of vehicles. My rank and job afforded me opportunities to go outside the green zone for official purposes, however.

Let me share with you an experience I had which I never wish to have repeated. Saddam Hussein’s regime was responsible for gross human rights abuses, including indiscriminate killings and dumping of bodies in unmarked locations under his rule. Shortly after the toppling of Baghdad, mass graves were beginning to be discovered, identified and excavated. Once, three colleagues and I were able to secure vehicles to drive to a mass grave site. It was surreal. Even before we arrived at the site, we saw from a distance mounds of airborne dust because volunteers were using backhoes to dig up the graves. And then, as we inched closer, we heard the wailing of women and men searching for their loved ones. There appeared to be an organized effort to provide assistance to families of the victims and to identify the remains as best they could.

We also had a chance to talk to ordinary Iraqis on this trip while at a stop that we had made along the way to the grave site. I remember one guy thanked President Bush for the overthrow of Saddam. Now, I don’t know what that same person would have said some years down the road, but initially there seemed to be a lot of goodwill toward us and the coalition. This was a decisive time in our relationship with Iraq. Decisions we made shortly after the toppling of Baghdad had long-term repercussions, as many critics have noted. It was painful to witness the looting of museums and other places of culture that went unprotected because the coalition forces could not be everywhere. And naturally, the U.S. military, coalition and civilian deaths, as well as the untold suffering, saddens me. All I can say is that we did our best, on a course we thought was right, and I hope that the great country that Iraq is will emerge strong and resilient.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in International Affairs, Georgetown University (1976–1980)

MA in Justice, American University (1993–1994)

Joined the Foreign Service (1986)

Paris, France—Cultural Affairs Office, Public Diplomacy Section (1988–1990)

Port-au-Prince, Haiti—Cultural Affairs Officer (CAO) (1990–1993)

Mbabane, eSwatini—Public Affairs Officer (PAO) (1996–1999)

Washington, D.C.—Africa Bureau for Public Diplomacy, Planning and Coordination Officer (PACO) (2002–2004)

Kabul, Afghanistan—CAO (2013–2015)