The United States underwent great political change following the end of World War II, not only fully abandoning its isolationist tendencies, but also contending for and succeeding in establishing international preeminence against the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War.

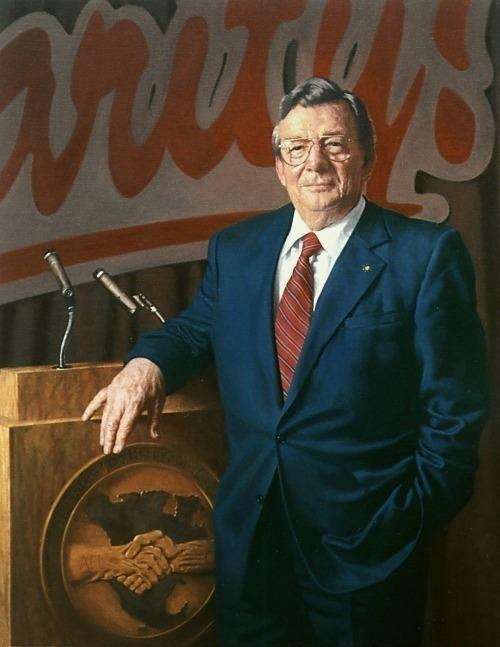

During the same time period, the U.S. additionally witnessed political change in its approaches to labor efforts in the Foreign Service. However, the transformation here does not appear to follow a similar positive trend; as Lane Kirkland notes, the value of labor attachés in the Foreign Service significantly decreased, as did the value that officers placed on the labor attaché program in the context of their overarching career.

And yet, in Kirkland’s opinion, neither the Department of Labor nor any labor unions were at fault for this declining presence. On the one hand, he argued that the State Department had actually been a hindering factor to the The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) achieving its full potential by forbidding its incorporation of the labor attaché program. On the other hand, Kirkland noted that Foreign Service personnel did not know the full extent of labor mechanisms that were at their disposal, with the incident involving UN Ambassador Albright’s—admittedly understandable—ignorance of The Tripartite Advisory Panel on International Labor Standards’ (TAPILS) existence highlighting this.

Finally, this depreciation in value of labor efforts in the Foreign Service may not be as negative as it seems. By the late ‘90s, the AFL-CIO had developed its own estimable foreign service branch, thus perhaps needing to rely less on the Foreign Service in its international endeavours than before. Furthermore, the lack of labor specialists in the Foreign Service certainly did not mean that no one was competent on such issues; on the contrary, Kirkland observed that certain individuals who had absolutely no background in the field could prove incredibly insightful and interesting to work with, often more so than those individuals who superficially exuded competence and sophistication.

Prior to joining the AFL, Kirkland served as a Chief Mate in the Merchant Marine. Upon his return to the States, he devoted the majority of his Foreign Service career to the AFL/AFL-CIO, only taking a two-year stint as the Director of Research and Education for the International Union of Operating Engineers.

Lane Kirkland’s interview was conducted by Morris Weisz on June 15, 1998.

Read Lane Kirkland’s full oral history HERE.

Drafted by: Will Shao

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“Many of the people who go through it are not particularly oriented toward the trade union movement, and regard these posts as stepping stones up the Foreign Service ladder; they do not have a sense or any intention of devoting their career to trade union affairs.”

Lost Renown: Q: Anyhow, Lane, let’s continue with any observations you have about the function of labor attachés in the Foreign Service: what are the advantages and disadvantages of having them there? And what are your feelings about the Marshall Plan and labor’s participation in it?

KIRKLAND: Well, as far as labor attachés are concerned, I think they had greater value years ago than perhaps they do today. Forty or fifty years ago, The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) had only a limited number of people abroad working in the international arena, and (a) the Federation had a significant voice in the appointment and development of labor attachés and their assignments, and (b) they filled a function that I think was and still is essential for providing an interface with the worker movements in various important countries all around the world.

I’m also not so sure that that function is as important to the labor movement today as it was in days past. In the first place, (a) the AFL-CIO—through its institutes—now has quite an extensive foreign service of its own. And (b) I think the labor attaché program, to the extent that it still exists, has been pretty much sublimated by the Foreign Service establishment. Many of the people who go through it are not particularly oriented toward the trade union movement, and regard these posts as stepping stones up the Foreign Service ladder; they do not have a sense or any intention of devoting their career to trade union affairs. So, although I—as I did while I was the President of AFL-CIO—still make a number of overtures and presentations to the State Department, I don’t have the feeling I once did that they should save and strengthen the labor attaché program.

Q: You’re right. The training program we had, that first training program I told you about, involved training good people, top-notch Foreign Service Officers, some of them in the trade union movement. And the trade unionists who were trained under our program got good jobs with the AFL-CIO frequently rather than with the Foreign Service. But the program was a year of immersion in labor and labor-related problems. That program is now reduced from one year to three weeks, during which they not only cover labor (and I still lecture there occasionally), but they also have to cover human rights in the broader field.

KIRKLAND: Yes.

Q: Now I would hope that we could get people interested if we in the Foreign Service could get the State Department to realize the broader needs. We’re interested in trade: a labor attaché can really help with our trade program. Maybe that’s not the thing that’s closest to your mind, but certainly it’s close to the—How else can you expect to have a human rights program, or a trade program, or a science program? One of the guests at my house recently was a guy who’s married to or close to Phil Arno’s widow. He was a science attaché who happened to have a good trade union sense, and served with us in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Well, the more you can infiltrate the Foreign Service with people who have an understanding of international labor affairs in broader aspects, the greater the possibilities are of getting people at the higher levels of the State Department to be aware of the importance of labor issues.

“I have known ambassadors in some countries, for example, who had absolutely no labor background whatsoever but turned out to be extremely good and interesting.”

Don’t Judge a Book by its Cover: Q: Yes, those are advantages not only to the government, but also to the labor movement, because they are people at the top level who have an understanding.

KIRKLAND: I have no quarrel with that whatsoever, but I think it depends far more on individual talents and proclivities—

Q: Absolutely.

KIRKLAND: —than it does on whatever set of boxes or systems are in place. I have known ambassadors in some countries, for example, who had absolutely no labor background whatsoever but turned out to be extremely good and interesting. We had very good relations with them. However, they were often succeeded by people who you would expect would be fairly sophisticated, but were turkeys.

I recall in the Soviet Union, before the fall of the Iron Curtain, there was a man on the embassy staff, who on his own initiative—he was an economics officer—undertook to establish contacts with trade union dissidents in the Soviet Union, contacts that ultimately became very important to us when we were able to begin operating over there. He was so good that I went to Larry Eagleburger and asked Eagleburger to appoint him, in addition to his other responsibilities, as labor attaché. His name was Mike Gafulo, and he was the first labor attaché in the Soviet Embassy.

Q: Oh, yes.

KIRKLAND: Terrific guy. Most of the contacts that we had over there, aside from some of the earlier dissidents who had reached out to us, we got from Mike Gafulo. He had gone out of his way to get to know them, and he weathered efforts by the Soviet officialdom to squelch him and get him out of the country, mainly because Jack Matlock gave him latitude and backed him up.

Q: There’s another good guy, Matlock.

KIRKLAND: Yes. Matlock had no history in the trade union movement, but I think he had a sense of the importance of civil society.

Q: He certainly did.

KIRKLAND: I recall when I was allowed to visit Poland—let’s see I think it was in 1989 or ‘90—I was over there for the 10th anniversary of Solidarity. Then, by virtue of an invitation from the City Council, I went to a human rights conference in what was then Leningrad. I got word from Matlock—this was close to Labor Day—that he wanted to have a reception for American Labor Day in the Spaso House, and he wanted me to come and preside at that reception. So we gave him an invitation list of 90 to 100 people from all over the Soviet Union, from as far as Sakhalin, Kazakhstan, the Kuzbas, Siberia, and even Vorkuta. I stayed at the Spaso House while we had this reception. It was a great affair: we divided the guests up and took little groups of these various people, spent a little time schmoozing with them, and then rotated around. The interesting thing is that I encouraged Matlock to include some prominent members of the American press on the invitation list. I thought this was perhaps a newsworthy affair, so he added five or six of them from the leading American journals and networks: none of them showed up.

Q: Really?

KIRKLAND: Except somebody from Radio Liberty. None of them showed up, so it was a nonevent.

Q: They had some good people there, including the guy who’s been writing for “The New Yorker” lately.

KIRKLAND: None of them were there; none of them came. It being Labor Day, I guess they were off in their dachas somewhere.

“I don’t think it’s the labor movement’s fault at all.”

Unfair Blame: Q: There is a responsibility that the Labor Department and the trade union movement have, which mustn’t be hidden. You—the American Trade Union movement—had the opportunity to have a voice in the administration of the State Department through two ways: first, to encourage the Labor Department to exercise its authority as a full member of the State Department’s Foreign Service Review Board. That has not been taken advantage of by recent Secretaries of Labor, who have a voice there. Instead, they send a lower representative, who is very assiduous and attends the meeting but cannot do the sort of thing that Phil Kaiser did when he was a member of the Board of the Foreign Service: he pounded his fist and got the AFL-CIO—the AFL and the CIO together—to help pound his fist and exercise their existing authority. The trade union movement is to blame, I think, for not pushing the government in that respect—

KIRKLAND: I don’t think that’s true at all.

Q: Oh, good. Please tell me why not? You don’t think they have any responsibility, or you don’t think they’re exercising it?

KIRKLAND: I don’t think it’s the labor movement’s fault at all. In the first place, there’s been a view that the Labor Department should take over the labor attaché program. That was resisted for years by the labor people in the State Department who were opposed to that idea.

Q: That’s a function of the State Department, but exercising the authority they have as a member of the Board of the Foreign Service—that is an important thing, which Reich did not do. I spoke to him personally about it.

KIRKLAND: All I’m saying is that that’s not the fault of the labor movement.

. . .

KIRKLAND: I don’t know whether it’s had a meeting in recent years, but at the time when the United States withdrew from the International Labor Organization (ILO), we created another Cabinet committee which still theoretically exists. This was supposedly chaired by the Secretary of Labor, with representation from State, Commerce, the National Security Advisor’s Office, the AFL-CIO, and the Business Council. All policy relating to the ILO was supposed to be cleared through that committee, which would meet from time to time, which it did during my tenure: the basis of our return to the ILO was worked out through that entity. We additionally created a committee through this entity known as The Tripartite Advisory Panel on International Labor Standards (TAPILS) to review ILO conventions and see if we could not begin to—

Q: —enforce them?

KIRKLAND: —bring them to the Senate for ratification on a basis of consensus, although it was a difficult process that required tripartite consensus. The initial break from the old Eisenhower deal with Senator Bricker led to the submission of the first series of ILO conventions to the Senate for ratification. Some of them, mostly relatively non-controversial, were in fact ratified in the first batch of ILO ratifications since before the Bricker Amendment issue was hot. That body is still supposedly in existence, but I don’t recall that it met during Reich’s tenure at all, or whether it’s met since.

I do know that after I retired, when I was a public delegate to the United Nations (UN) at the 50th General Assembly, the issues debated in the American delegation when Madeleine Albright was the UN Ambassador concerned the budget and the U.S. people at the UN. It seemed to be moving in the direction of sacrificing a contribution to the ILO, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO), and a couple of other agencies, in order to preserve maximum contribution to the ILO. I protested this on the grounds that there was this interagency body in existence, and that no such decision should ever be considered without its involvement. Madeleine didn’t know such a thing even existed.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

United States Merchant Marine Academy 1941–1942

B.S. in International Shipping, School of Foreign Service, 1946–1948

Georgetown University

Joined the American Federation of Labor 1948

Washington, D.C.—Director of Research and Education, International 1958–1960

Union of Operating Engineers

Washington, D.C.—Executive Assistant to President George Meany, 1960–1969

The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations

(AFL-CIO)

Washington, D.C.—Secretary-Treasurer, AFL-CIO 1969–1979

Washington, D.C.—President, AFL-CIO 1979–1995