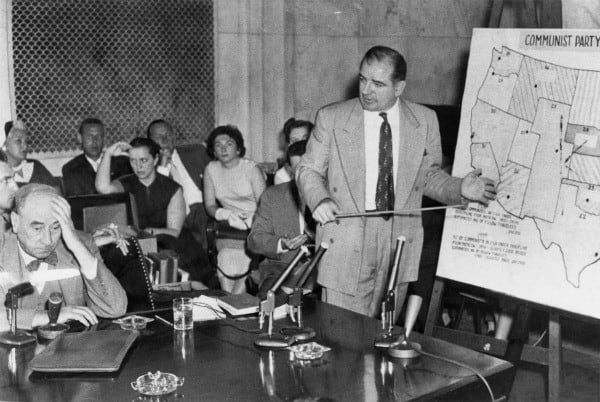

The inauspicious rise of Joseph McCarthy began in 1950, when the Wisconsin senator was asked to give a speech at the Ohio County Republican Women’s Club. Until then McCarthy had had a mediocre political career. But that day, despite the humble venue, he managed to give a speech that would catapult him to new heights of political influence. In his speech, McCarthy alleged that he had a list of 205 State Department employees who were known members of the Communist Party yet were still working for the Department.

McCarthy’s accusation, though baseless and fictitious, stirred up deeply-held fears of many Americans in the Cold War era. The idea that communists were “shaping the policy of the State Department,” as McCarthy claimed, terrified Americans who had been conditioned to be constantly weary of the threat of Soviet expansionism.

In the years before the rise of McCarthy, President Truman had created the Federal Employee Loyalty Program, which investigated potentially disloyal government employees. The Republican-led House Un-American Activities Committee had already been involved in many highly publicized cases against well-known entertainers who supposedly harbored communist sympathies. But McCarthy’s constant baseless accusations created a chaotic witch hunt that made many government employees, particularly Foreign Service officers, feel constantly threatened.

By the early 1950s, the public mood towards diplomats had soured. Some Foreign Service officers felt they were being punished whenever they reported events that politicians did not want to hear. Things worsened in 1952, when McCarthy became head of the Committee of Government Operations, allowing him to create constant bogus investigations. McCarthy even targeted high-level statesmen who had long been respected in the world of foreign policy, like George Marshall (the architect of the Marshall Plan), and Dean Acheson, the secretary of State, who he accused of having failed to prevent China from becoming communist. To make things worse, McCarthy also began pushing LGBT+ employees out of their positions, accusing them of being subversive and susceptible to blackmail. It seemed like no one was safe. Although McCarthy never unearthed any actual instances of disloyalty, his accusations destroyed the careers of many FSOs. He held such sway over American politics that even President Eisenhower was fearful of contradicting him. In 1954, McCarthy began targeting the U.S Army. These attacks would ultimately result in his fall from grace, causing him to lose the support of many Americans. Still, the damage had been done. Despite only having been in power for a few short years, McCarthy caused irreparable damage to the careers and lives of many Foreign Service Officers.

Caroline Service was one individual who had her life dramatically disrupted by McCarthyism. Service’s husband John “Jack” Service was fired from the State Department because of the same accusation that haunted Secretary of State Acheson—he was one of the State Department employees blamed for having failed to prevent China’s turn to communism. Ironically, Acheson had once fired Service over supposed disloyalty. Service knew her husband wasn’t to blame, and that politicians were lashing out at FSOs who had served in China. She felt that FSOs like John were essentially being scapegoated for a larger geopolitical issue. Not only did Service have to deal with John’s firing, she was also forced to spend a year alone in India with her children because she had arrived there ahead of Jack, who was fired before he could make it to India. Although she made the best of her time in India, her story illustrates the chaos that McCarthy created for Foreign Service families.

John S. Service was perhaps one of the most famous victims of McCarthyism. His case typified the increasing division within the State Department. Service had spent much of his career working throughout China as a political officer. Throughout the 1940s, Service’s political reporting was critical of Chiang Kai-Shek’s nationalist government, which he viewed as harsh and economically and militarily weak. When he wrote a report that suggested that Mao Zedong was a better leader, it ended up being leaked and he was recalled to Washington D.C. over the controversial report. He returned to China in a different position, and was again recalled when he suggested that the U.S. could prevent war casualties by providing aid to the Chinese Communists. But these clashes between Service and the State Department were only the beginning. Service was arrested in 1945 and accused of leaking classified reports to Amerasia, a left-learning magazine. Although Service was cleared of that charge, his past came back to haunt him when McCarthy came into power. McCarthy promptly accused Service of being a communist, and he was fired by Secretary of State Acheson in 1951. Service fought the ruling and rejoined the Foreign Service in 1956. The controversy over whether Service was just reporting facts that the State Department didn’t want to hear, or was actually disloyal was indicative of the political fissures growing in the State Department John Service’s lengthy saga shows the growing suspicion and division that ultimately led to the rise of McCarthyism, and the destructive character of McCarthyism itself.

Meanwhile, FSO John Melby had a very different experience than Caroline and John Service but also fell victim to McCarthyism. While working in Moscow, Melby began an affair with the American playwright Lillian Hellman. Hellman had been a target of the House Un-American Affairs Committee for allegedly being a member of the Communist Party. Melby himself was not a communist at all, but his relationship with Lillian was enough to get him fired from the State Department. Saddled with an ineffectual lawyer and a biased hearing, Melby didn’t stand a chance. He also had to deal with the media attention his case garnered. Ultimately, Melby was yet another FSO pushed out of the Foreign Service by McCarthyism.

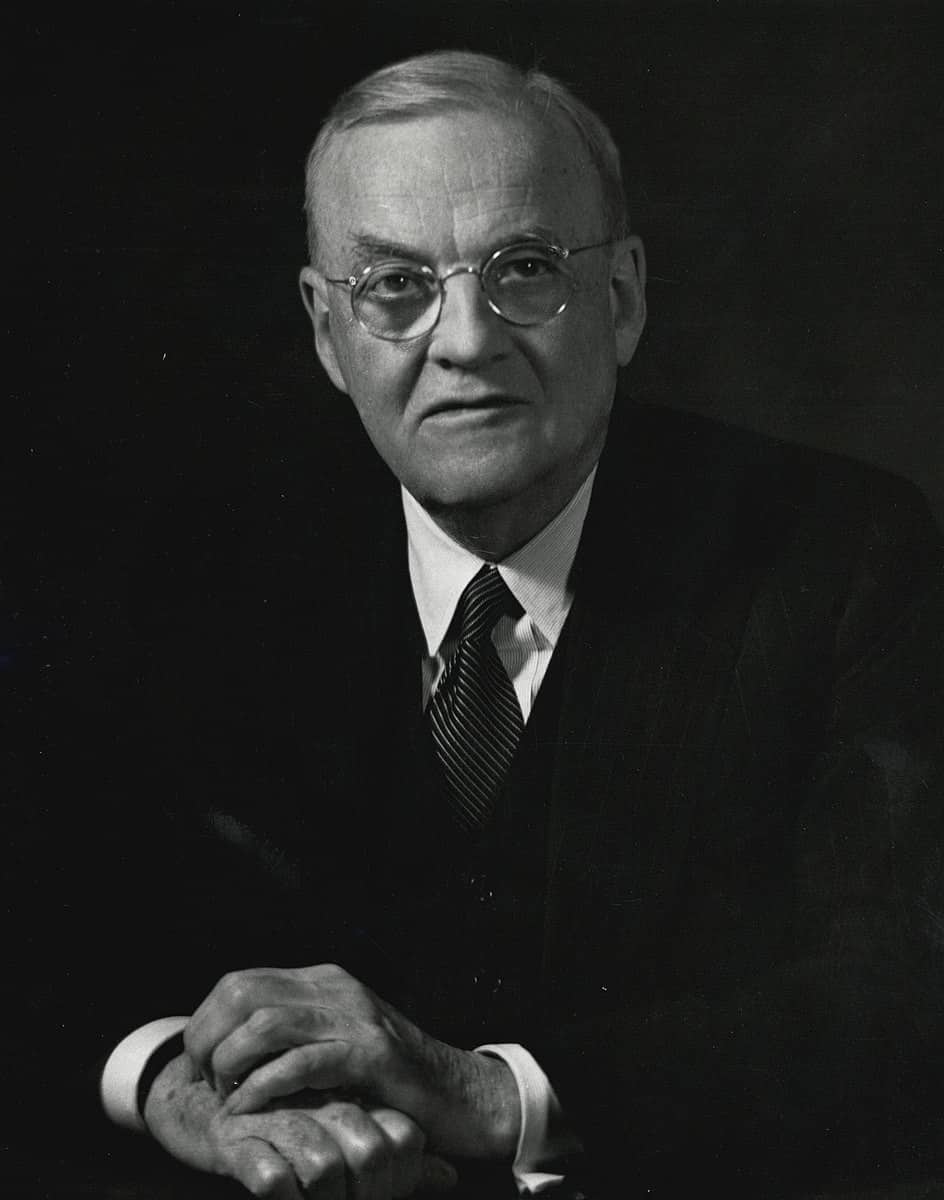

As Senator McCarthy reigned over the Second Red Scare, the Eisenhower administration consolidated the United States’ foreign policy of containment against communism abroad. President Eisnehower wanted a secretary of state tough against communism, which would not only strengthen America’s foreign policy, but to also combat the criticisms Senator McCarthy had on the State Department and its officers. He appointed John Foster Dulles as the secretary of state.

Dulles was a consequence of McCarthy. McCarthy indirectly forced him to have a stronger hand in the State Department. His notion of “positive loyalty,” addressed to his officers on his first day, demanding that he will not “be caught with another Alger Hiss on my hands.” Hiss was convicted of perjury after having perjured himself in regards to testimony about his alleged involvement in a Soviet spy ring before and during World War II. The case brought the Department of State under attack from McCarthy and his allies. The reason was because defenders of Hiss, such as Secretary Dean Acheson “declared that President Truman’s opponents were making a sacrificial lamb out of Hiss.” It was an opportunity for McCarthy to declare the defenders of Hiss allies of communism or in support of the red culture. In turn, when Dulles came into office, his policy of “positive loyalty” demanded obedience to his authority and the authority of the state.

Positive loyalty was a doctrine that led to uncertainty amongst State Department’s officers; it was a consequence of McCarthyism. It was Dulles demanding that his officers be loyal to him and to the department at all costs. It aimed at ensuring that people would not taint the image of the department with anything deemed communist. He wanted to prevent feeding into McCarthy’s Red Scare campaign. It worked to an extent, but the results were not positive.

Foreign Service officers were not certain if Dulles would back them up if falsely accused. In an interview with ADST, Fisher Howe, a former Deputy of Chief of the Bureau of Intelligence and Research, had the doctrine referred to as having “sent a chill throughout the department.” It was a critical error of Dulles to have allowed such a policy in the department and stimulate fear amongst the officers. No one wanted to make a mistake because they were not certain of keeping their job or their trust with the department. Howe continued with how the policy was “was so awful in contrast to what Acheson had done.”

Robert Asher’s interview with ADST believed that Dulles “rightly had reason to expect that State Department employees would fall in cheerfully with his views. I felt that if I didn’t, it was not a good idea to stick around.” Asher saw the environment changing, and that perhaps it wasn’t a good idea to stay in the department.

In this “moment” in U.S. diplomatic history, we see that the rise of McCarthyism had enormous consequences in the United States Department of State. Unfortunately for many diplomats, Secretary Dulles kept a similar tone of command in response. Foreign affairs professionals share their stories on the environment of the State Department during the Red Scare. Several oral histories in the ADST collection have more first person accounts of the McCarthy era.

Read Fisher Howe’s full oral history HERE

Read Robert Asher’s full oral history HERE

Read Caroline Service’s full oral history HERE

Read John Service’s full oral history HERE

Read John Melby’s full oral history HERE

Read more about Eisenhower Administration’s Foreign Policy HERE.

Read more about Secretary John Foster Dulles HERE.

Read more about Alger Hiss HERE.

Drafted by Artemis Katsaris and Derek Gutierrez

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

Robert Asher

Frankfurt, Germany—Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces 1945

Geneva, Switzerland—Temporary Committee for Devastated Areas 1947–1950

Washington, D.C.—Special Assistant Secretary for Economic Affairs 1951–1954

“I felt that if I didn’t, it was not a good idea to stick around and, if I could go elsewhere.”

The authoritative Secretary Dulles:

But after Eisenhower’s election in 1952, Dulles became Secretary and brought with him his passion for security pacts with every “free” country in the world as an anti-communist measure. I couldn’t see this. Partly because of my broad international outlook, and partly because it seemed too much like an elephant and a rabbit being harnessed together. A U.S. security and mutual defense treaty with Ecuador or a small weak country elsewhere just didn’t seem to me a very realistic thing. Dulles talked to departmental employees about “positive loyalty” and getting behind him. I think he rightly had reason to expect that State Department employees would fall in cheerfully with his views. I felt that if I didn’t, it was not a good idea to stick around and, if I could go elsewhere, I would be happier and so would the State Department.”

*************************************************

Fisher Howe

Washington, D.C.—INR, Deputy Chief 1950–1956

“The positive loyalty was just a cap on it when he came out with that.”

Positive Loyalty as the new law:

Q: When Secretary of State Dulles took office, he used the phrase when he met the department for the first time he used the phrase, “ positive loyalty”, which sort of sent a chill throughout the department. What was the feeling towards Dulles as far as both his work as a secretary of state but also as a protector of his department?

HOWE: Dulles made an absolutely critical error in coming on board when he made that “positive loyalty” statement. Acheson a week before had gotten everybody out—in the whole department—out in the parking lot, it was a beautiful day—and out in the parking lot out back and gave a farewell speech that just had everybody in total tears of loyalty. Dulles said, “All right. I’ll get the whole State Department out there and I’ll give a speech.” He talked about his team in football terms. The people he was getting in. Doc Lawry was one of them, who had been a great football player at Princeton. Butch Fisher, wonderful guy, I think was legal advisor, and he had been a football player also at Princeton. And Dulles from Princeton. Anyway, it just bombed. It was so awful in contrast to what Acheson had done.

Q: It was a rainy day too, wasn’t it?

HOWE: Yes. Everything went against him. He was just poorly advised to do it. The positive loyalty was just a cap on it when he came out with that. Then the appointments of Scott McCloud and the other fellow whose name I can’t remember. There was a constant concern. And Dulles was just not the friendly personality that his brother Allen was.

*************************************************

Caroline Service (spouse)

Beijing, China 1935–1937

New Delhi, India 1950

FSO Husband John “Jack” Service fired 1951

“The Republican Administration was determined to get people out of the Foreign Service who had been in the China service.”

The Chaos of McCarthyism:

It was while we were in Berkeley with my parents that McCarthy gave his famous—maybe I should say infamous—speech in Wheeling, West Virginia, about card-carrying communists in the State Department. When I think of McCarthy the one word to describe him that comes to my mind is “Yahoo.” McCarthy had a list of over 100 names, so he said, of people in the State Department who were “communists,” or “card-carrying communists.” He gave no names, but each description of a “subversive person” had a number and a description. None of the descriptions fit Jack. Jack phoned the State Department to ask what we should do. Should he come back to Washington? We were booked on a freighter out of Seattle bound for Madras on March 11. The Department said that Jack was not on McCarthy’s list and that we should continue to India, which we did. On March 11 we sailed for a month-long trip to India via Japan and the Philippines. The passage across the north Pacific at that time of year was stormy…About halfway across the ocean the radio operator came to our cabin one evening and said to Jack that the news was talking about a man named Service that McCarthy was after. McCarthy was saying that Service had “lost China” and so on. So Jack rushed up to the radio room to listen and heard a lot more. The radio man had a friend in Los Angeles who was a ham operator, and our radio man was able to get more information from him about what was going on in Washington. The next day a cable came to the ship from the State Department telling Jack to return to Washington from Japan. We were given the option of my staying in Japan with the children, returning to Washington with Jack, or going on…but he never got there. Everyone was more than helpful. Finally I decided that I was going to give a big party because I thought that Jack would get to Delhi by Christmas. He went through several more hearings in Washington and was always cleared. But that didn’t make any difference. I think that by this time McCarthyism had become so all-pervasive that someone had to go.

Well because he had had a lot to do with the so-called “loss of China,” in quotes…But even without that the China Hands, as they were called- Edmund Clubb, John Carter Vincent, and John Davies were easy targets. John Davies was finally fired out-of-hand, I think, right after the election of 1954. John Carter Vincent and Edmund Clubb, being over 50, were forced into retirement. It was because of China. Because China had gone communist…These people had “Lost China.” It was so crazy. You can just tear your hair sometimes. The ironic thing is that it was Nixon who finally got John Davies fired. Dulles was the Secretary of State. The Republican Administration was determined to get people out of the Foreign Service who had been in the China service. You can’t say it was a plot; it’s just that politically it was a good drum to beat. They wanted to show the public that Republicans weren’t “soft on communism.”… it was as though the country was facing a great outside menace which was inside the country. It just drove people nuts to think that China was not pro-American anymore…It was like a red flag to a bull to mention China except in pejorative terms…McCarthy frightened Americans. He frightened the public. I was frightened. Now I’ll tell you. I wasn’t frightened in China. I wasn’t frightened the year I spent alone in India. I wasn’t frightened traveling around the world. But I was frightened by McCarthy. I thought what is he going to do to us? What is he going to do to our children?

*************************************************

John “Jack” Service

Beijing, China 1935–1937

Shanghai, China—Rotation Officer 1938-1941

Chunking, China—Consul/ Political Officer 1942-1945

Fired from the State Department 1951

“They said, “We’re FBI. You’re under arrest,” and so on.”

The Many Trials of John Service:

This was the beginning of controversy and disagreement in Washington, you might say. In 1944 when I’d come home, everyone was interested in what I had to say and there was pretty general agreement. But this time people were already beginning to divide a little bit. Some people in the State Department—Drumright, for instance—were arguing that there was a civil war in China, the Communists are in rebellion, we can’t have any dealings with them. There were people in the Far Eastern section, particularly the old Japan contingent, Grew, Dooman, and other people, who represented the anti-Communist point of view. The European people were anti-Communist, bitterly anti-Communist. They couldn’t believe that there was any difference between Chinese Communists and Russian Communists. So, you began then at this period to have a sort of splitting in the Department.

About six thirty, the doorbell of the apartment rang. I opened the door, and here were the two guys that I’d seen in the State Department. They said, “We’re FBI. You’re under arrest,” and so on. They came in and I was naturally a bit stunned. They asked if they could search the place, and not being smart or experienced, I said yes. They said, “Where are the papers? Where are the papers?” Well, they didn’t find any papers. They thought I had the place stacked full of my reports. I said, “My reports are all in my desk at the State Department.” Anyway, they searched the place, and they found a sort of private code that Davies and we “advisers” used writing among ourselves. Our letters had to go over Japanese territory in Burma. There was always a possibility of the plane being shot down, so we had an agreed on private code of using fictitious names. Stilwell wasn’t Stilwell. I forget—just code names, this sort of thing. Sort of silly. This was how Dixie got started. We referred to Yenan as Dixie, and so it was the Dixie Mission. I was taken to the FBI offices and we had a long talk. I said, “This is crazy.” I was perfectly willing to cooperate. We had a long, long, long session. They kept referring to little notebooks. They obviously knew all of my movements. They kept jogging my memory. “Did you see so and so? When was it?” Finally I said, [chuckling] “You’ve got the dates here. I can’t remember.” I don’t know how long it took, but they wrote out a statement which I finally signed. Later on, of course, my lawyer was very sorry about that. I don’t think we need to go into it. We’ll include this in the record, can’t we?

We were taken to jail and processed in. This was very late at night. This is not much to waste time over. Processing into jail is about the same, I suppose, anywhere. There’s an account in Solzhenitsyn’s In the First Circle of a young chap who was a foreign office guy being taken to Lyublyanka, and it’s not too different from the District of Columbia jail.

You’re forced to strip—you take off all your clothes—shoved into a shower room, wash off thoroughly, given a one piece garment. Mine was ripped in the crotch, and I said, “Can’t I get another one?” “You better take it. It gets pretty cold up there in the cell block, ha, ha, ha.” You know, this sort of thing. The attitude of the people in these places is pretty chilling. You’re put into a cell. You’ve got a blanket and a mattress, absolutely nothing else in there. They won’t let you have a belt or anything like that. This was very late at night by the time this was all finished . . . . After all, you see, I was charged under the Espionage Act, which is silly because none of us were accused of espionage really. But there wasn’t any other act apparently that could be used. Using the Espionage Act, of course, gave the Chinese Kuomintang press a field day because they cheerfully and loudly printed that I was a Japanese agent, Japanese spy.

Hoover obviously had a great interest in the case. One of McCarthy’s favorite lines was that Hoover had said there was a hundred percent air tight case “against Service.” Well, when we pinned Hoover down—he never would reply directly—but he replied through the Department of Justice, he said he’d never made such a statement. This was a statement that I think very obviously he had made or FBI people had made. All this is not really answering why I was arrested, but describing maybe how it happened. I think unquestionably FBI interest in the case was prompted by FBI cooperation with the Chinese secret police under Tai Li.

Well, the State Department was completely unorganized for anything. They had no security division or security section. They had one man who was sort of liaison with the FBI and a couple other agencies, who was in charge. They just left security entirely up to the FBI. The FBI apparently suspected everyone in FE, or practically everyone in FE, because in their eyes the whole State Department policy of being agreeable to collaboration, cooperation with Chinese Communists, was just crazy. It was one that they couldn’t fathom.

There isn’t very much to say about it. It’s just something we had to get through, that was all. I think, all things considered, we came out of it well. It might have been much worse, as far as the effect on the family goes. On Virginia, I’m not sure. There’s so many factors involved. I think that probably my being in China and away from the family for almost six years was harder on the family, Caroline and me, and on the children perhaps than the Amerasia case or the firing. As I say, you can’t just pinpoint it on the case. The life we led, the long separations, and my emotional involvement in China, all these things affected the family.

*************************************************

John F. Melby

Moscow, Soviet Union 1943–1945

Chungking, China 1945–1948

Washington, D.C.—Philippine Desk 1948–1953

“They were McCarthy stooges, all of them . . . .”

The Scandal

I first met Lillian in Moscow when I was there. Well, we had an affair. And it went on for 40 years. An association. And that was the only charge against me from the Department, that I had maintained an association with one Lillian Hellman, who is a member of the Communist Party, who is alleged to be a member. It didn’t say she was. All I could say was, “Yes. It’s true. So what?” It was out of the McCarthy era of suspicion. It was in the very early stages of it. The charges were made and the charges were laid. And I was informed of the charges but I was never allowed to know who had made the charges. I was never permitted to confront those who had accused me of this, or had accused her of anything. It was a true star chamber operation. And it would, many years later, after Bob Newman finally got the FBI reports, that there was no substance to the charges against Lillian. She had been accused by one of the FBI informants of being a communist, who later turned out to be a liar. He’d accused everyone in the world of it . . . They were a bunch of finks. They were McCarthy stooges, all of them . . . . They didn’t know what it was all about. They were administering what was, at this time, a new branch of law, namely administrative law. And most lawyers, except for two or three, four maybe; no lawyer had to have any experience with administrative law. There wasn’t anything to go on. My lawyer was a very conservative, well-known practitioner before the Federal Communications Commission. And he just sat there, during my hearing, with his mouth hanging open. He didn’t know what to say. He couldn’t answer, he couldn’t ask a question. He didn’t understand what was going on. What kind of legal proceeding is this? And I was just sort of on my own, because he didn’t know what to do. He had an assistant, a young man named Ted Barron, who was a little more knowledgeable and tried to salvage things.

In the end, finally, I was suspended. And I decided to get rid of Scharfeld and get another lawyer, who turned out to be Joseph Volpe who had been general counsel of the Atomic Energy Commission. He would handle all of the security problems for the Atomic Energy Commission, including–who was the man who was then one of his clients, Robert Oppenheimer, one of the best men in the business. But by this time, it was too late. Joe did a magnificent job on it, but the board obviously wasn’t even listening to him. You could tell from their questions. He would talk, put forth an oration, and they weren’t even listening. They didn’t care. They weren’t interested. They had already made up their minds: I had not told the truth, I was lying. I was therefore a security risk. There was never any question of loyalty in my case. It was just pure security. I had lied. I hadn’t told the truth. Therefore, I was not reliable…Lillian. She was a communist. And I’d said I didn’t believe it. I was lying because their informants from the FBI said that she was. But they wouldn’t let her testify. They wouldn’t let me know who had made the charges against her. I didn’t know what I was defending. I could either take their word for it, which turned out to be wrong, or I could recant. Well, I wasn’t going to do that.

. . . there were hundreds [of investigations] going on. And nobody was talking to anybody else. You’d walk down the street and you’d see somebody who you knew charges were laid against; you’d cross the street so that you wouldn’t have to speak to them. It was an incredible period. One of the charges that was laid against me was, “Mr. Melby, we get a report that you’ve been spending a lot of time hanging around hotel lobbies. Do you think that while you’re going through this, it’s wise for you to appear in public?” I said, “What are you talking about? Hotel lobbies are a public place. I’ll go there anytime I want.”