Organized labor holds power in the histories of countries all across the world, coming to the forefront as a political entity at the turn of the twentieth century. In unifying the working class with a political consciousness, the labor movement quickly gained might and influence—demanding integration into government dealings, as typified by the role of labor officers in the U.S. Information Agency (USIA) in the 1950s and 60s.

Yet, the labor movement shares deep roots with folk music, songs shared orally that comment on national cultures. In the mid-twentieth century, a revival of the folk tradition carried powerful political messages through a populace, often commenting on the state of labor workers and unions, as exemplified in songs like “Union Burying Ground” by preeminent folk artist Woody Guthrie. Many such folk musicians reached fame supporting union efforts at rallies and gatherings nationwide, integrating music into the fabric of the labor movement irrevocably.

Joe Glazer, a long-standing labor officer and advisor, exemplified the role of labor in international dealings, finding his start in the Rebel Workers Union in Akron, Ohio in the early 1950s before developing a decades-long career in the federal government. Upon entering USIA in 1961, Glazer moved to Mexico City, where his love for music played a key role in developing cultural diplomacy.

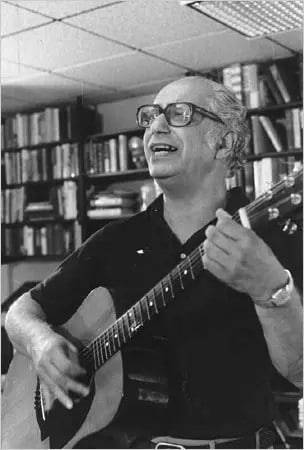

Yet, Glazer was perhaps better known as a folk musician, frequently referred to as “labor’s troubadour,” recording more than thirty albums in his career. Glazer’s story exemplifies the power of the arts in the labor movement, starting with his hiring to the Rebel Workers Union on the basis of his college performance experience. In this “moment,” Glazer speaks to the strength of music in his government career in labor, developing a folk song program in Mexico, and continuing his folk song performances for the government well after retirement.

Joe Glazer’s interview was conducted by Morris Weisz on March 31, 1992.

Read Joe Glazer’s full oral history HERE.

Drafted by Miranda Allegar

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“This is better than the pyramids.”

Music to the People:

I started at the U.S. Cultural Center there which had thousands of people learning English. Also they taught Spanish, but the big thing was teaching English and other things. They had art exhibits and speakers and movies and so on. I started a small folk song club for—mostly English folk songs—to learn in a way to supplement their English. Each time I’d have two or three songs with the expanded English and the Spanish translation. We started out with about 10 to 15 or 20 people. I thought it would be a small thing but this thing started growing. We wound up moving to bigger rooms. We finally wound up having it weekly in the auditorium.

Q: Really?

Yes.

Q: Was this a concert of yours or just a participatory—?

A folk song club where we’d learn songs and then I’d sing some songs and we’d have people from the audience singing songs in English and in Spanish.

Q: Why do you say this has little to do with the labor? This was illustrative of the type of participation by a guy with any sort of background in the work that was being done there. We had labor attachés with other backgrounds who—

I suppose, but at any rate, this was probably the most successful thing I’d ever think of. We’d get 150, 200 people, standing room, big crowds every week. It got mentioned in the—Mexico being a great tourist town—Things to Do, and they’d list this thing every Wednesday night or whenever it was.

Q: Needless to say the embassy nor the USIA didn’t pay you extra for that.

Oh Jesus. As a matter of fact it used to cost me extra. It would end up late at night and then I’d have to take a cab back to the house. Our house being a little off the beaten track, they didn’t like to go there. I still remember today, ”Yo pago doble” (I’ll pay you double). You learn the Mexican tricks. It was cheap enough. So instead of costing 60 cents it cost double. . .

Usually there’s an . . . American culture. I’d do cowboy songs, some railroad songs, whatever. Labor. I worked in labor songs each week that explained. We had hundreds of people there. A lot of them were students studying English at the cultural center. People from all over the city. I remember one time a couple comes in, obviously tourists. They sit in and they sing and enjoy. Then they’d come up to me later and they said, “Oh, we enjoyed this Mr. Glazer. This is better than the pyramids.”

Q: Well, Joe, do you know anything about the degree to which that type of thing continued after you left?

That’s a good question. I don’t know what happened afterward. I had a couple young guys that I was sort of training. And there was a young Mexican guy who was good in English who knew a lot of American folk songs and Spanish folk songs, and when I was out of town, I had him fill in for me. As a matter of fact, he wanted to go to the states. Later I got him to go to the states where he became a guitar teacher and he married an American girl. But I don’t know if it continued much. Even though we had really institutionalized it, I guess we should have tried to figure out a way to do it. Whether they could have done it without me—

Q: It requires somebody who is not American to continue the work because the continuity cannot be supplied.

Songs around the World:

I was retired and I get this call from—I was talking actually, believe it or not, on the phone to somebody and I get this call from England. I guess it was a reporter. He wanted me to do something. I said, “I’m kind of busy.” I said, “Wait a minute. I’ve got another call.”

I come back and I say, “I’m not making this up. I’ve got a call from England and I’ll get back to you.”

. . . the ambassador there was [Charles] Price. Very nice fellow. A banker from Kansas I guess he was. He ran an annual Labor Day affair for the labor leaders which was very smart. He generally had oh, country music or some western angle there. You know Americana.

Then he said one time to [Roger] Schrader, “Is there any kind of labor music or something? We ought to do something different.”

Schrader says, “Well the only thing is we’ve got Joe Glazer.”

He says, “Who’s he?” Of course he’s never heard of me.

He said, “Well, he sings labor songs.”

He says, “Is he any good?”

He says, “Yes.”

He says, “Give me one of his records.”

So he gives him one of my records. . . . Not political stuff. A good labor record.

Price says, “Well, this isn’t my kind of stuff. But,” he says, “the guy’s a good singer. . . .”

The guy was smart. He said, “It will go over well with the labor guys there.”

So they arranged to have me go over there. . . .

I not only was on Nixon’s list. I was on another list. See I was on two lists there. There was a USIA blacklist. As a matter of fact, I told Schrader about it. He mentioned it to the ambassador. He wasn’t worried about it. It’s interesting. This guy felt secure enough that he didn’t—

Q: If that were a career man, he couldn’t have done it.

Oh yes. That’s right. As Schrader said, “He’s ok and you won’t have any trouble with him.”

MRS. GLAZER: Stupid business. This is a memo. We got this from Victor—

Q: We’re now reading from a memorandum from the White House and it’s a memorandum addressed to a number of people. . . . It’s from somebody named Joanne Gordon. It says, “The attached list of sponsors of the Salute to Victor Reuther should be added to your copy of the opponents list.” It’s dated May 16th, 1972 and it’s got Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Glazer listed in the ADA salute to Victor Reuther which was held on that day. . . . Anyway, the attached list of sponsors was put on the opponents list and there we are.

Now there was also, the USIA for a while they had—I don’t know if they had—there were certain names that were blacklisted that when they were proposed to speak overseas included people like Walter Cronkite. I guess somebody had proposed me and somebody got a hold of this list. . . .

Q: Well, the point is that in spite of the fact that you were on these various lists, this guy, this ambassador, a republican presumably, a powerful player, didn’t feel it necessary to clear it or to change it or anything like that. Which is illustrative of the fact that there are certain areas in which politicals who may be in disagreement with you have a little bit more leeway in what to do whereas the career officer would reconsider.

Of course being an old hand at this, I put on a hell of a show. I have to tell you that. I had a couple of little things I had to watch out for. At this time, [Arthur] Scargill [British trade unionist] had this bitter strike going on which the labor movement was split about. Most of them I guess were against it. I laid off. Originally I would normally do a coal mining song. . . .This was probably 1982 or ’83, something like that. It was at the height of this

bitter, bitter coal strike. A lot of the labor leaders just hated Scargill’s guts. So I avoided that. I did a lot of stuff on solidarity. I brought in Samuel Gompers “born,” I said, “just a few miles down the road.” One guy says, “You’re pointing in the wrong direction. . . .”

Q: But it was a successful concert. You never got any sort of criticism of having been there. And so far as you know the ambassador didn’t get any criticism either.

Nobody complained. . . . As a matter of fact, what I did at the end by the way, before I sang the last song, I said, “I want to say a word about the ambassador here. . . .” I said, “I think everybody realizes that he and I have somewhat different political philosophies. He is not what we call a labor man.” They all kind of smiled. “But he is sensitive to the importance of labor in this country. He went out of his way to bring me here, to bring people here so you could see one aspect of American labor.

Q: That was very good.

Roger Schrader afterwards said, “That was fantastic.” I worked on a couple of things. I don’t know if you’ve ever run into this—I did “Too Old to Work, Too Young to Die”? I talked about this. Somebody had picked up a parody in England when there was a battle about Nye Bevan and Herbert Morrison.

Q: Left and right within the labor party.

Yes. They adapted my song. They said, “Who will take care of you, how you get by when you’re too left for Herbie and too right for Nye.”

Q: That was very good.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in physics and mathematics, Brooklyn College 1934–1938

Joined the Foreign Service 1961

Mexico City, Mexico—First Labor Information Officer 1961–1965

Washington, D.C.—Labor Advisor 1965–1981