The work of the U.S. Foreign Service encompasses more than just advancing U.S. interests abroad. A critical part of it remains the mission of development support to the host country. In many instances, this mission is achieved through not only diplomatic meetings and negotiation, but also through music. After the song We Are the World was composed to support Africa during a difficult time of famine, Robert Berg was one of the four people who worked on taking it to the next crucial step: to allocate the funds to help end hunger.

Ever since his first visit to Nigeria on a development mission in 1965, Robert Berg has served during his career in various capacities in Africa—think tanks, non-profit, and private sector—all with a common vision of advancing development. However, this crucial task—both for the host country and the world—does not come easy. On his very first USAID trip to Nigeria, Berg encountered the internal turmoil of the country. As Berg believes, there should be two independent voices: a political one telling a country often what it wants to hear, and a development voice telling them sometimes the hard truth. In less than a year on duty in his initial assignment, Berg became convinced that the onset of a civil war was imminent. He returned to Washington D.C. to report the hard truth that was facing the future of the Nigerian people.

Robert J. Berg’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on August 15, 2012.

Read Robert J. Berg’s full oral history HERE.

For more Moments on the intersection between music and foreign service: The Power of Music in the Labor Movement, Laying it between the lines – Music Diplomacy in Shanghai, Michael Jackson in Gabon – Just Beat it, and Arias Cabalettas and Foreign Affairs.

Drafted by Bagul Mammedova

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“I kept seeing posters all over with pictures of prototypical Igbo faces on them that said ‘Report Strangers to the Police.’ I had concluded that civil war was inevitable . . . .”

Early Indications of Civil War: I came back to the States in late 1965 convinced there would be a civil war in Nigeria. I knew the Emirs in the North were agitating against the millions of Igbos in their midst as these Easterners were commercially aggressive and successful—a real source of resentment by Northerners. Outbreaks between Muslims and Christians, which some said were orchestrated by the Emirs, were taking place with considerable and increasingly deadly violence. It was very disturbing.

So when I returned to Washington in late 1965 I went to see folks at the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research and reported what I had seen and that I had concluded that civil war was inevitable if these trends continued. They asked perfectly correct questions…How well do you know Nigeria? How many times have you been there so do you have a basis of trends and comparisons? I truthfully told them I was just a kid, this was my first trip to Africa, etc., etc., but that the facts on the ground were too dramatic to ignore, that there was a real power struggle going on between the North and the South and the Igbos were at the front line of that struggle.

I was grateful when the Bureau sent a message to our embassy in Lagos and to the three American consulates around the country (Ibadan, Kaduna, and Enugu) asking if any of them saw anything wrong going on. I got a call telling me that none of these posts saw any signs of a coming civil war…a position they maintained for 18 months until just a few weeks before civil war broke out in July 1967.

That war was a disaster for Nigeria, particularly for those in the East—the breakaway Biafra—and for our aid program part of which, in the East of the country, had to be entirely suspended and the rest of which was greatly slowed.

“It was New York without the amenities.”

Now it is much worse: I think you just have to be born on the side of the street you want to be on.

In 1970 I was asked to take over that office [Capital Development office within the AID mission in Lagos.] I arrived in Lagos to work for a curmudgeon of a boss who didn’t believe in welcoming parties (except for him)—a chap who later worked for me. I had an office of a few finance officers, a group of engineers, and industrial development staff. And I had a tribally balanced support staff. Knowing the portfolio and the players on the Nigerian team, I determined that my main mission would be to somehow change the mindset of Nigerian officials regarding USAID’s help. Instead of their saying “your projects” when they found a problem in them, I wanted them to say “my projects need help.” I tried everything I could to get the national government to take ownership. They would talk about “your project” and I would say “I don’t have any projects,” that we were just there to help them on their projects. When we found a problem in a project I would call the PermSec and say “You know that your project in the far northeast is facing some serious difficulties now. It happens that I can line up and cover an airplane charter to go up there if you have anyone you want to send up there to straighten this out, and if you do send someone, I could send our engineer up with that person to carry his briefcase.” Over time the Ministry of Finance saw what we were doing by helping them take charge of their development and they were enthusiastic actors. We had great relations . . . .

“. . . .You would see wheel barrels with signs on them saying ‘We will Rise Again’”

Post-war Biafra: My family and I took an auto tour of that area and saw an absolutely devastated land. On the other hand, all the people we met and saw were determined to rebuild. In other parts of Nigeria, there would be trucks with signs on them saying things like “God Protects Us All” but in Eastern Nigeria where there were few trucks. Instead, you would see wheel barrels with signs on them saying “We will Rise Again.” The University of Nsukka, which had received tremendous help from AID and Michigan State University and was considered by the winning military to be the intellectual center of Biafra, had practically been erased. Now classes were held in an open field with the students sitting on the ground and the professors standing leaning against sawhorses. We tried what we could to help rebuild the East, but the Federal Government did not have that as a high priority. Nonetheless, we had plenty of work to do to help deliver what was then the largest portfolio of projects AID had in Africa. And in addition, my immediate boss, the Mission program officer, managed to be away during two budgeting seasons in a row, so I got to have that experience, too, which I thoroughly enjoyed.

“We should all have such problems.”

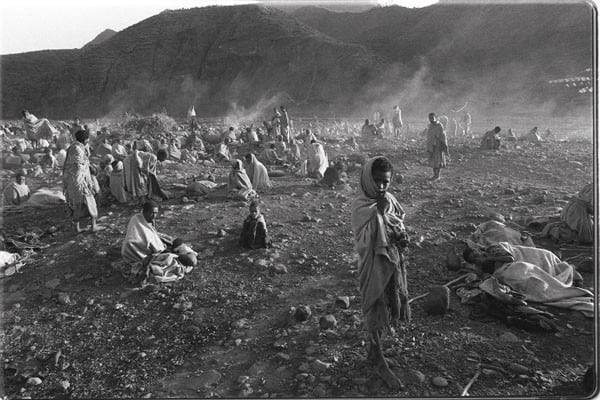

Music and Development Assistance: In 1984 a huge famine (a result of drought, awful governance, and pest infestations) struck Ethiopia, the second major famine in a dozen years. Some parts of Ethiopia were reported by NGOs to be like deep dust moonscapes—only these were scattered with the bodies of animals and people. NGOs in the U.S. were particularly concerned with the slow U.S. response. Every so often a group of us would put on a public program on Capitol Hill or hold a demonstration near the White House and each time the Reagan Administration would suddenly find another $50million in relief after maintaining that they had no more money. Later Senator John Danforth showed President Reagan his own films of what was going on in Ethiopia and the President cried over what he saw and ordered his staffs to mobilize the government to work to prevent further famines in Africa.

To mobilize support for relief efforts and to generate monies to help, Michael Jackson, Lionel Richie, and Stevie Wonder wrote the song “We Are the World,” and enlisted 45 of the best known popular musicians to sing it, including Ray Charles, Diana Ross, Bruce Springsteen, Dionne Warwick, Willie Nelson, Tina Turner, and Paul Simon. The song became an instant worldwide hit, becoming the biggest selling single record in history, earning quadruple platinum status and a profit of $63Million. The leaders in follow-up, Quincy Jones and Harry Belafonte, asked four of us to allocate the money: a wonderful colleague at the Rockefeller Foundation, two academics, and me. We four were raised in a different tradition so we talked about soliciting proposals, reviewing them—all standard donor business practices. Jones and Belafonte were horrified. They wanted us to get the money out the door NOW so that they could move on and solve Latin America’s problems in a few months. So the four of us made up our Christmas gift lists and shoveled that money out the door. It was amazing. Most all of the money went to groups with real humanitarian and reconstruction relief capabilities.

The only real problem the spending committee had was that every time we felt we had finished our work in would come a note saying that “We are the World” was the most popular music on Brazilian elevators or some such, and with the note would be another million dollar check. We should all have such problems.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA, University of Southern California

MBA in Behavioral Science, University of Chicago

Joined USAID in 1965

Nigeria—Capital Development Officer 1965, 1970–1972

Washington D.C.—Senior Fellow for Overseas Development Council 1982–1986

New York—Senior Advisor for UNICEF and World Summit for Children 1989

New York—Senior Advisor for UN Economic Commission for Africa 1995–2005