The Biden administration nominated Ambassador Julieta Valls Noyes to serve as assistant secretary of state for the department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM). A career diplomat, Noyes previously served as deputy assistant secretary of the Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs, where she managed relations between Western Europe and the EU from 2014 to 2015––a time in which refugees fleeing conflict from the Middle East were streaming into Europe seeking asylum.

Coordinating with international organizations like the UNHCR, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and the International Organization for Migration, PRM provides relief and resettlement to displaced populations around the world and promotes policies aimed at increasing life-sustaining aid and family planning. Issues of refugees and family planning are not only critically important in the foreign policy realm, but often carry with them a political charge here at home.

This “Moment” in U.S. diplomatic history features the work of PRM through the perspective of its very first head, Ambassador Phyllis Oakley. Ambassador Oakley’s long career spanned from the 1970s into the 1990s; in 1993 she became the first assistant secretary for the newly-created PRM, which had just been reorganized from the Office of Refugee Affairs. Raised to the level of bureau, this reorganization reflected a renewed focus on the issues of both refugees and family planning—topics that were perceived as neglected by the preceding presidential administrations, and which would prove immensely important in the first decade following the end of the Cold War.

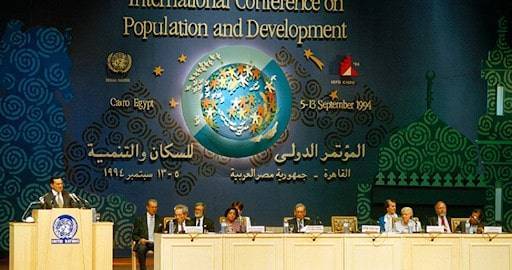

From her oral history interview, Ambassador Oakley provides insight into how the Office of Refugee Affairs became PRM, and why she was selected to be its top administrator. She recounts what it felt like to take the position as a woman––which was in part because she was a woman––and the numerous challenges she faced in her time there. Those included multilateral negotiations at the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo, Egypt and the problems presented by the numerous refugee crises of the 1990s. Capped off with her reflection on the progress the bureau made during that time, Oakley’s insight helps illuminate the work of PRM and possible challenges Ambassador Noyes will face in this position.

Phyllis Oakley’s interview was conducted on March 8, 2000 by Charles Stuart Kennedy.

Read Oakley’s full interview HERE.

Read more about what it has been like for Foreign Service women HERE.

Drafted by Daniel Schoolenberg

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“. . . . the Clinton people were scurrying around looking for Foreign Service officers, particularly women.”

The New Administration:

OAKLEY: I think changes are always a little messy. There is a period when there are more questions than answers…. I think the Clinton people took a greater interest in the appointments of deputies than most other administrations; they were interested in diversity and placing many new people, but it was not a very well organized effort.

One of the interesting aspects of the Department’s changeover was the arrival of this slew of new people who came with Christopher, including Tim Wirth—former senator from Colorado who was appointed as the new Under Secretary for Global Affairs (an office designated as “G”). I remember that in early 1993, the Clinton people were scurrying around looking for Foreign Service officers, particularly women. I was asked by Wirth whether I would be interested in working on human rights, democracy, and labor. I really was not because those issues had never been front and center in my interests. So I didn’t think that would be a good fit. Then he asked whether I would be interested in working in the refugee bureau as the deputy director, and that was a lot more interesting.

“. . . . there was a “clean sweep” mentality among the newcomers.”

Reorganization of Refugee office:

[Then] a new administration took office in 1993. This was a Democratic administration after Republicans had occupied the White House for twelve years. So there was a “clean sweep” mentality among the newcomers, which was fine by me because after two years in INR, although the subject matter was fascinating, I was ready to move on.

…I had been offered a couple of jobs by Tim Wirth. He came to the Department as a committed environmentalist and supporter of family planning. With all his Congressional experience, he knew the private, non-governmental world of NGOs and activists, and was very knowledgeable about many aspects of the issues that he was expected to handle, and he was energetic and determined… Wirth had been a senator; he had come to Congress in what was called the “Class of 1974″—a group that had opposed the Vietnam War and which was eager to see reforms enacted. They were “Young Turks” who had held out a lot of hope for Bobby Kennedy, but after his assassination, it took them a long time to rise to power. It was a remarkable group of Congressmen.

In Tim’s reorganization… the Office of Refugee Affairs became a bureau by adding population to refugee and migration issues. Tim Wirth felt passionately about population issues, and I think his reorganization was backed by the White House that wanted to make it more of a political issue and not just development. As you may remember, one of Clinton’s first acts was to reverse our position on “Mexico City language.” That is a complicated issue, but essentially it barred U.S. government funds from being allocated to international family planning organizations which espoused international family planning if that organization’s work included support for abortion—even if those programs were funded by other resources and conducted where abortion was legal. The restriction had been first put in place by Reagan at a conference on women held in Mexico City—and hence the name.

AID traditionally had been the lead agency on population programs, and therefore U.S. policy, working with both NGOs and international organizations. Tim felt that the issue was more important and broader than just implementation, and that the Department had to become the main policy making engine on family planning.

The offer that Tim made to me was Deputy Director of the Office of Refugee Affairs or Principal Deputy. The director then was Warren Zimmermann, whom I didn’t know personally, although I was familiar with his reputation because had been our ambassador to Yugoslavia and he had also worked on many European issues. I became the principal deputy in September 1993 and served under [Wirth] until 1997. I think there was always the understanding that if and when Warren left, I would assume the duties of office director.

“. . . . this was another time for me when it was useful to be a woman.”

Becoming Assistant Secretary of the new Bureau:

By early 1993, it became clear that Warren Zimmermann [then head of the Office of Refugee Affairs] would not be selected to be the first assistant secretary of the new bureau. The administration was looking for diversity; this was another time for me when it was useful to be a woman. There just were not enough of them at the assistant secretary level in the Department.

Q: Did you find it somewhat uncomfortable to appear to belong to a “privileged” class?

OAKLEY: It was uncomfortable. I would have been more than happy to continue as Warren’s deputy – that would have suited me fine. But I think when he saw that he would not be appointed as assistant secretary and that there was no other senior assignment on the horizon, he decided to retire, despite the fact that he was recognized as an outstanding officer who had served his government very well.

At that point, a wonderful thing happened to me. Meg Greenfield, the editor of the editorial page of The Washington Post and a good friend, heard about the political competition for PRM. She wrote an editorial saying that the bureau already had on its staff a real professional woman who was well qualified and that she thought it was most unfortunate that others were being considered to be assistant secretary, particularly outsiders who had very little if any knowledge of refugee affairs. I think that editorial had a tremendous impact.

I found the selection process to be quite fascinating because I had never seen such an interplay between those who worked on political placement and Foreign Service politics. In the end, given all the politics, I was almost surprised but very pleased when I became the administration’s candidate for the Assistant Secretaryship.

“It was a huge affair.”

1994 Cairo Conference on Population:

Two days after being sworn in in a brief ceremony in early September 1994, I left for Cairo for the UN Conference on Population and Development (ICPD). That was a real experience. Our delegation was filled with political appointees, NGOs, members of Congress, and representatives of various departments. The Vice President came through Cairo for a brief appearance at the conference. Tim Wirth was there with a number of his former congressional staffers, who continued to work for him in many ways. There were numerous NGOs in attendance at a parallel, non-governmental conference. It was a huge affair.

There had been a great deal of preparatory work at the UN so that the draft resolution would be acceptable to the broad range of interests represented in Cairo. The negotiating process in the UN is very complicated, with bracketed language when there is disagreement. The wording on teenagers, abortion, maternal health, and on what assistance should be provided by the developed world became key to success by one side or the other. I must say that my experiences with these resolutions made me wonder after they were drafted what their meaning really was. But there were a lot of tough negotiations on language—it is very interesting that the Iranians, who had been hit by a population explosion, became quite amenable and helpful to our efforts to prevent restrictive language on reproductive health and family planning.

Our problems were primarily with Muslim regimes governed by fundamentalists and with those governments on which the Catholic Church had strong influence, like many in Latin America. Some chose to take a hard line; others did not. China was very sensitive about its one child policy, which had been widely criticized. So there were many currents at play in Cairo.

“I think… refugee issues are going to become increasingly difficult.”

Refugee Issues in the 1990s:

It was a new world for me. I had dealt with many of the NGOs and UNHCR when I was the Afghanistan desk officer and was worrying about Afghan refugees. Also I had seen many of these organizations in action when I was in Pakistan working with the Afghan humanitarian program. The Bureau for Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM) had about 100 people, both from the Civil Service and Foreign Service. A lot of Foreign Service officers were introduced to refugee problems and work around the world in the course of their overseas tours and became passionate about the problem.

There had been earlier huge refugee problems, starting with the Vietnamese. The U.S. government and the predecessors of the PRM bureau organized themselves to address that particular challenge. Efforts were well coordinated among the Department of Health and Human Services, INS, State Department, and UN agencies. That became the model for later efforts. Then came the Afghan problem in the early ‘80s; that was not so much an issue of resettlement as it was a matter of feeding and housing a displaced mass of people, well over two million. We had to work closely with Pakistan, which set itself up bureaucratically to direct and organize the assistance.

At the end of the Gulf War, the U.S. faced the question of Iraqi refugees. Then came the Balkans, Bosnia particularly, which again was more a relief effort than a resettlement problem. So the 1990s were a period of great effort on refugees and humanitarian assistance.

In the 1970s and 1980s, refugee crises were not in Africa—they were in Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq. These were situations that resulted primarily from the Cold War and anti-communism. But in the 1990s, refugees in Africa had come to the forefront of humanitarian concern. Countries are no longer as welcoming to refugees as they used to be. I think that about 25 percent of all Africans fall into the refugee category; that is an astounding statistic.

The challenge of bringing to the U.S. [groups] who have never had an opportunity at anything resembling home life, is huge, as you can well imagine. They need to be taught all the fundamentals of living and then how to become economically self-sufficient in American society. I think all these migration and refugee issues are going to become increasingly difficult. When Afghans came to the U.S., they were mostly from an educated class and the same is true for refugees from the Soviet Union. The Vietnamese had a more difficult adaptation process, but most of them managed it very well with strong families. The ones that have problems are primarily illiterate or from tribes and therefore only accustomed to a very small clan. They have the hardest time making the adjustment.

Each refugee-migrant case was and is a story in itself. You can’t generalize about refugees or migrants – all cases are unique.

“I felt that the bureau had done terrific work.”

Leaving PRM:

Q: How long were you the assistant secretary?

OAKLEY: I worked as PRM Assistant Secretary for three years. In early 1997, there was a change of Secretary of State and that obviously changed lots of people and the way the Department operated. I had loved the challenge of being the PRM Assistant Secretary; I had had ideas of what might be done for women’s health in refugee camps, for promoting certain projects, for coordinating migration issues and working closely with Doris Meisner, the head of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, etc., but Foreign Service officers do not tend to stay in jobs for any extended period.

I felt that the bureau had done terrific work in the bureau for refugees. The staff was great; it had more women than men by the way. We even had some meetings where there were only one or two men. It was wonderful for me to be able to demonstrate in the Department what we, a largely feminine staff, were able to achieve.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in Political Science, Northwestern University 1952–1956

MA in International Relations, Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy 1956–1957

Entered the Foreign Service 1957

Various locations––Wife of Foreign Service Officer 1958–1974

Reinstatement as Foreign Service Officer 1974

Washington, DC––NEA/PAB-Afghanistan and Bangladesh Affairs 1982–1985

Islamabad, Pakistan––USAID Staff 1989–1991

Washington, DC—Population, Refugees and Migration, Assistant Secretary 1994–1997

Washington, DC—Intelligence and Research, Assistant Secretary 1997–1999