With a presidential visit comes months of preparation and stress. While big embassies with hundreds of staff members are often old hands at orchestrating big diplomatic events, it is not the same for small consulates. Such was the case when President Reagan and around 1,000 people, including 300 journalists, visited the small U.S. consulate in Shanghai in 1984, which only had a dozen FSOs and thirty-five FSNs (Foreign Service Nationals) at that time.

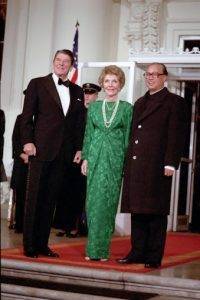

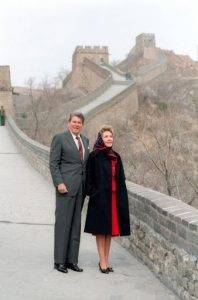

After the United States established official relations with the People’s Republic of China and embraced the One China principle in 1979, Chinese paramount leader Deng Xiaoping’s visit to the U.S. marked the first of many high-level exchanges between the two countries. One such reciprocal exchange involved President Reagan going to China and Premier Zhao Ziyang coming to the U.S. in 1984, when Reagan impressed dignitaries with his occasional effort to speak Chinese. In addition, it had been the first visit of a U.S. president to China since President Nixon’s groundbreaking visit in 1971, which was the first key step in normalizing U.S.-China relations.

In this “Moment in U.S. Diplomatic History,” we see how Public Affairs Officer Lloyd Neighbors handled the White House press and orchestrated President Reagan’s visit to the small consulate in Shanghai. He noted how planning of the diplomatic visit took months, and how the small consulate coordinated a sizable delegation of around 1,000 people. Neighbors, who had formidable Chinese language skills, had previously studied in Taichung, Taiwan, and was American Center Director in Kaohsiung, Taiwan. In his later career, Neighbors spent many more years in China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, including at the U.S. embassy in Beijing where he served as Chief of Press and Culture.

Lloyd Neighbor’s interview was conducted by David Reuther on February 6, 2013.

Read Lloyd Neighbor’s full oral history HERE.

Drafted by Alek Blonk

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“The planning for the trip took six months of intense effort – like the allied landing at Normandy.”

Months of planning:

Mike Deaver was Reagan’s public affairs Svengali. He plotted out in great detail how the trip to China was going to look in the United States, how the story would run in the 79 papers and on television, and how the White House could get the best propaganda bang for the buck.

In the fall of 1983 Deaver came to China with an advance team of 16 White House specialists. The delegation went first to Beijing, then to Xian and Guilin, scouting out possible sites for the visit. Finally, they came to Shanghai. And remember, this was six months before the visit. From the beginning we made the rounds of all the possible sites, walking through possible scenarios. We knew that the president wanted to make a speech at a university. He also wanted to show support for American business, in particular for joint ventures with Chinese firms, which were becoming popular at the time. Deaver also wanted to have some other event that might look good on camera.

So we started visiting all these possible sites and talking to the FAOs (Foreign Affairs Offices) and to the Chinese officials who would be involved in making the visit a success.

Three months after this scouting trip, Deaver came back again with an advance team of 30-some people. By this time, the schedule was beginning to fall into place. We were getting more and more into the details of the trip. Then three weeks before the visit, the onslaught began. About 140 Secret Service agents and WHCA (White House Communications Agency) commo specialists arrived. And they were accompanied by the so-called press advance—two media campaign specialists and two administrative wizards who handled the hotel, baggage, travel arrangements for the horde of journalists traveling with the president.

In doing a POTUS (President of the United States) visit to Beijing, the White House could call on an embassy staff of maybe 120 American officers and 200 locals. They had a lot of foot soldiers to throw into battle. The situation in Shanghai was different. Shanghai was a tiny post, 10 or 12 officers and 35 FSNs. And to handle the White House press there was just me and my six FSNs. As it turned out, press events were going to be the heart of the Reagan visit to Shanghai. . . .

“In Shanghai, no one on the press side had any idea what was going on.”

A big deal for a small consulate:

The most important event for Reagan in Shanghai was his speech to students at Fudan University. His first-day schedule looked like this: airport arrival ceremony, visit to a U.S.-China joint-venture factory, speech at Fudan University, banquet hosted by the president for Shanghai leaders. Early the next morning he would go to a commune and look at farmers and visit their house and then proceed to Air Force One.

This was a complicated schedule for such a short visit. We’ve got to make sure the press—both U.S. and Chinese—can efficiently cover each event. Now doing a presidential visit in Tokyo or London or Paris, it’s difficult, very complicated. But these embassies are old hands at high-level visits. They’ve seen the president scores of times, they know what the White House requires, and they have all the necessary equipment on hand.

In Shanghai, no one on the press side had any idea what was going on. I’d never done one of these visits. I soon discovered, oh, every place the president comes, we have to have press risers so that the cameramen can be high enough to get a shot. In most countries nowadays risers are available for hire. You pay the money and a company installs them for you. Doesn’t work that way in Shanghai. No, we have to hire carpenters to build the risers for every event and a podium for a potential press conference. The press conference venue of course has to have a blue-drape backdrop. So we hire a seamstress to make this gigantic blue drape. The site for the press conference is an old auditorium at the Jin Jiang Hotel with a podium about 100-feet wide. We have this enormous curtain hanging all across the back. . . .

“I’m just running around like crazy and this Mark Weinberg fellow is screaming at me for doubling up the press accommodations.”

Screaming and the gnashing of teeth:

At the time of the Reagan visit, the Chinese hadn’t had much experience with events on this scale, particularly events that would attract frenzied media attention. Despite this lack of experience with the press, the Chinese were past masters at being hospitable. They knew how to organize programs and didn’t appreciate criticism of their efforts.

White House officials, under Mr. Deaver’s public-affairs direction, knew exactly what they wanted. All too often that was not what the Chinese wanted. Result: a lot of gnashing of teeth and screaming.

One of the problems we had in Shanghai was acquiring enough hotel rooms to accommodate 300 White House journalists. There weren’t enough to go around. Some of the press would have to share hotel rooms. This was an important development, so I sent this information in a cable back to the White House.

Well, on the day of the visit, the press planes arrived and complete chaos ensued. And the White House Advance Mark Weinberg was screaming at me because he had just discovered that the journalists had to share rooms, and the journalists were really mad. And so Weinberg was screaming at me. And I basically told him, “I sent you a cable about it. If you don’t read your in-box, it’s your fault.”

To take the 300 journalists into town, we had 16 buses waiting on the tarmac. Most of the journalists would go directly to the Jin Jiang Hotel and the Press Filing Center. A small contingent, however, were scheduled to cover Reagan’s first event at the joint-venture factory. Unfortunately, Chinese security had made the travel much more difficult by deciding the American press charter plane with 300 press aboard could not fly from Beijing to Shanghai. The Chinese said, “You do not have permission to fly this charter plane from Beijing to Shanghai. You have to take a Chinese carrier.” So they split up the 300 traveling press into three different planes.

We had it arranged so that the group covering the factory visit would fly on the first plane. Then of course we got word that the first plane had broken down and would be late. And so the planes arrived and no one knew where they’re going. And so we’ve got these 16 buses and no one knows quite what to do. I’m just running around like crazy and this Mark Weinberg fellow is screaming at me for doubling up the press accommodations. Finally it hits me. Getting the press onto the correct buses was not my job. Someone else had that assignment. I was supposed to get on my bus and get the reporters into the hotel. So that’s the big lesson I learned. If you are not assigned to do something, you can’t worry about it. Each team member has to do his own part, and things will work out—maybe. . . .

On the eve of D-Day, my wife Mary suddenly realized we were one table short in the Filing Center. Didn’t have enough space for an extra radio team that was coming in. She pulled aside the hotel staff and asked for an extra table. They scratched their heads for a moment and then led her to a back room where sat a big beautiful table. They started pulling it out into the corridor. But then one of them yelled, “Wait! You have to be very careful with that table! You have to cover it! That was where Nixon signed the Shanghai Communiqué!” I don’t know if the story was true, but they thought it was.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

Indiana University, BA, 1967

Starts doctoral studies at Indiana University, 1967

Joined the Foreign Service 1975

Kaohsiung, Taiwan—American Center Director 1977–1979

Shanghai, China—Branch Public Affairs Officer 1983–1987

Hong Kong—Public Affairs Officer 1989–1993

Beijing, China—Chief of Press and Culture 2000–2003