Sometimes, politics involves standing for one’s values, even if it goes against the beliefs of the system in charge and all of those around oneself. Dan and Jenny Neser made the decision to do just that, while living in the midst of Apartheid South Africa in the 1960s. As soon as these South Africans, natives of Pretoria, became aware that their country was a grounds for institutionalized racial segregation—fostered by the country’s government-controlling Afrikaans minority over the black majority— they dedicated their lives to openly and actively opposing the regime.

Dan Neser, while growing up in Pretoria, was immediately exposed to politics through legal connections because of his father’s position as a judge. After passing the bar exam, Dan got a job as a lawyer at an Akfrikaans law firm, maintaining a stable and respectable career. However, as the political situation progressed, Dan made the decision to leave his career to speak out against Apartheid officially. Dan and Jenny would devote their lives to Anti-Apartheid acitivism.

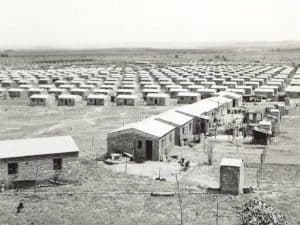

From the start of their outspoken criticism, many of their close friends regarded them as “crazy” for acts such as befriending black South Africans. The couple started their work primarily through the church, as founders of the Christian Institute in Pretoria. It was here where the Nesers developed close contacts with the black community, as it was one of the only integrated institutions at the time. Jenny ran a night school at the Institute, which helped the black community further their education in the climate where blacks were intentionally undereducated. Although the church acted as an outlet for unity, Dan was advised that going into politics would be the only way to bring about true change.

Taking this advice to heart, Dan went on to run for a seat in Parliament as a member of the United Party. Although aware of his slim chance of success, given that black South Africans had no suffrage along with the sly redistricting of the Nationalist Party, he used his campaign as a way to represent blacks as well as convince whites of the need for change. Although never holding official office, Dan had a successful political career as an active United Party member—lobbying, holding dinners, and meeting with influential figures. They worked closely with notable Anti-Apartheid figures, including Desmond Tutu and Beyers Naude. He developed this reputation in the political realm, and became a notable figure of the party, which led to his appointment on the President’s Council. Dan eventually served as a member of the commission which brought together members of opposing parties to establish the negotiations which eventually led to the end of apartheid.

In 1994, after forty-six years of institutionalization, Apartheid was finally abolished when the Nationalist Party and anti-Apartheid liberal parties negotiated terms for a new constitution that would allow for democratic elections. This was the result of decades of work, domestically and internationally, from those such as the Nesers. Upon Nelson Madela’s election as president of the new government, the African National Congress, the renowned leader established the country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The Commission acted as a body to uncover the human rights violations that occurred during this era. Its goal was to establish a peaceful means for the country to move forward—focusing on forgiving perpetrators of oppression, rather than prosecuting them.

The following excerpts illustrate the most notable moments of the Neser’s anti-Apartheid activism.

The Neser’s interview was conducted by Daniel F. Whitman on February 19, 2010.

Read the Neser’s full oral history HERE.

To read another “Moment” recounting anti-Apartheid activism, click HERE.

Drafted by Chelsea Cirillo

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“I mean we had lots of people say, ‘you are crazy’. Then look around today; we weren’t that crazy.”

Leaving a Stable Career:

DAN NESER: I was brought up in Pretoria, born and bred here really. My father happened to have been a judge in this division. The net result was a network of various other judges where I grew, particularly in later years. I started my practice at the sidebar in due course and passed the bar [exam]. I joined an Afrikaans firm to start off with after qualifying at Stellenbosch University as my LLB [Bachelor of Laws]. I joined the firm, Dyson, Douglas, Muller, and Mayer. Muller had become the minister of foreign affairs at the time. I did my articles there for two years and then I was offered a senior post and then a partnership.

Q: What was it that moved you to leave the firm?

DAN NESER: Well, I decided I was going to speak out against apartheid publicly (….) It wasn’t meant to be [a way to make a living]. I was convinced I could make a living anywhere. The big thing was figuring out where I could be the most effective and influential when I started my new career.

JENNY NESER: I would say that as soon as we became aware of what the political situation was––I would never have married you had you not felt that way. Both of us never minced our words. I thought you were jolly courageous in terms of where you were working. There wasn’t a single person who doubted that you thought apartheid was completely wrong. You always spoke out. Some of your partners, that one man, came over when we had a house full of black people. I think he just about expired. I mean we had lots of people say, “you are crazy”. Then look around today; we weren’t that crazy.

DAN NESER: I spent quite a while and went to see Beyers Naudé (….) He was instrumental in starting the Christian Institute. Jenny and I were both founders in the institute.

(….)

JENNY NESER: Most of our contacts were originally through the church, which is where there was mixing, but mainly through our church, which was the Church of the Province of South Africa [CPSA]. Your churches were integrated, but we made it our business to establish friendships with the people we met because we felt that we had to find out what was going on. Many of our friends came out of these church groups. I would say that although the churches were integrated, there were white churches here that didn’t really have black members. Then you would have a meeting on the diocese, and you would have the black community churches coming in. For instance, I started an educational program here because I was approached by the laborers in this area to say that they wanted to further their education. Some had had three years of education and they wanted to finish. They took a survey and said they couldn’t stand being in the rural areas and wanted to be industrial. Just speaking to the domestics, 80 percent of them are illiterate or semi-literate. A black friend of mine through the church and I started night schools in all the churches we could; some wouldn’t allow us to. We would run the schools four nights a week.

Q: Did the church provide a sort of neutral ground, sacred ground, where the police could not regulate?

JENNY NESER: Exactly, that is why the school I ran is here in church halls. The police would wait for us outside and force my students into the backs of their vans. The police would drive around until the curfew kicked in and then the student would be arrested. We ran the classes from quarter to eight until quarter to ten because we wanted to allow all domestic workers who had finished working to attend. Besides, the other laborers traditionally disappeared after work. There was a huge black population that would just disappear at night.

“ ‘Do you believe that you can break bread with members of your church?’ I said, ‘That’s all Dan and I want to do.’ “

Political Involvement:

JENNY NESSER: The interesting thing is that when Dan was involved with politics, we wanted to go to the townships, but you weren’t really allowed there as a white. We would go with some friends of ours, but when he was actually standing as a candidate for parliament, we decided he would have to get permission. What could happen would count against him standing in the election. It was quite interesting because I can remember that I once went to the chief of police here. I asked him if he was a Christian, he said, “Yes I am.” I said, “Do you believe that you can break bread with members of your church?” I said, “That’s all Dan and I want to do.” He looked at me like I was crazy, but I explained that that was why we wanted to go to the townships.

So, we went, but it was a tactical move on Dan’s part because they used everything they possibly could against a candidate who opposed the Nationalist Party. (….) This was part of standing as a candidate. Of course, you canvassed, and many other young folks were impressed that someone, young like him, was going to be brave enough to stand. (….)I think standing in this neck of the woods in an absolutely secure Nationalist Party seat, you’re probably more likely compared to the white electorate to consider giving them your vote. Whereas if you stood as a Progressive Party…[you were marginalized]. (….) I think Dan and I really felt it was no good just representing black people’s views. You had to persuade your white South Africans to change. It was jolly difficult. I know from canvassing.

(….)

There was great excitement that a young person would use up his savings and stand up against the government. We had a lovely team. Quite a lot of young Afrikaners canvassed the University of Pretoria. You felt that they wanted a change. It was quite exciting, actually. The results were a very great disappointment to us in terms of any possibility of winning the seat. I mean, he did better than anyone else in an absolutely secure Nationalist Party seat.

“Desmond said to me he would give serious consideration if the government would do three things.”

Influence from Notable Figures:

DAN NESER: There was this guy [Figglybum] who was doing the articles in German; he was one of Jenny’s contacts (….) He got out of jail and got permission to go to Jo’burg [Johannesburg] to do articles, the legal articles we had to do at the time to qualify as an advocate. He had spent six months qualifying and he felt he did not have enough experience. He asked me to see whether I couldn’t get permission for him to stay a bit longer to get a bit more experienced. I undertook to go and see Piet Koornhof, who was the minister of Bantu affairs at the time (….) I went to go see Piet Koornhof. He had discussed this with the police and could see no real problem, but he wanted to ask me a favor in return. Would I please persuade Desmond Tutu to accept an appointment to his Urban Black Council? He wanted to establish an Urban Black Council that could give him advice on the urban blacks (….) I went to see Tutu and said, “Well, this is what I’ve been asked to see you about; do you think he could join the Urban Black Council?” Desmond said to me he would give serious consideration if the government would do three things.

JENNY NESER: The first was to acknowledge the permanency of the urban blacks. You see the urban blacks were living here. There were two million people living in Soweto and they were considered temporary in a wide area. I mean it was ludicrous that they weren’t accepted but the moment you accepted them would affect the whole policy of apartheid

DAN NESER: He [Piet Koornhof] was overruled in the sense that he was giving an okay and they said you cannot give an okay. So interestingly enough this is what Desmond said. He said that he would never get that past the cabinet.

JENNY NESER: The other two requests were really for basic necessities of living. They were innocuous but the first one, demanding permanence of the urban blacks, was really changing the whole policy of South Africa. So that’s why he said he would never be able to get it through.

Q: You were the go-between in a way. This started with Figglybum who needed something that required you to go to Piet Koornhof. Piet Koornhof was willing to listen to you on the condition that you transmit a message to Desmond Tutu. Desmond Tutu came back to you with a message to go back to Piet Koornhof.

(….)

JENNY NESER: You see he [Tutu] is the only person I would say is of the stature alongside Mandela. I hate to make odious comparisons, but I don’t think his [Tutu’s] integrity is in dispute. He has allowed himself to criticize the government without saying he doesn’t like the ANC [African National Congress]. You feel that he is an honest citizen and that he wants the best for South Africa, whereas I’m afraid most of our politicians have really disappointed both Dan and me, and the masses. I mean that quite honestly. On occasion, for instance, I went to ask the head of SenTech whom we had met at a party. He was trained in Cuba. “What do you think of the foot soldiers who put you into power?” He just said to me, “Well, actually I don’t think of them.” I was totally flabbergasted, but then I would like to help you with the time span. When we talk about Pikale and this instance with Tutu is after you stood for those various elections.(….) I think he struggled to get Mandela free and to change the system and he wanted to go back to the church. I don’t get the impression, but maybe we’re wrong, that he really wanted to stand for political office. I think he actually preferred to be the conscience of the government. That is why I think he is so honorable. He has stuck by all his beliefs. Nor has he, you know, been sucked into being part of the gravy train.

“He was a Nationalist who decided things couldn’t be Nationalist any longer; things had to change.”

Working Toward Unity:

JENNY NESER: You were mainly invited through the Marie Commission and your friends. Dan then went through the formal way to get an opposition together. Marie was a judge. Why did you choose him if he was a Nationalist?

DAN NESER: I chose him because he was good at his job and being Nationalist no longer meant what it had. He was a Nationalist who decided things couldn’t be Nationalist any longer; things had to change.

I was successful in getting the two parties together under the umbrella of the Marie Commission. The commission had to decide whether it was possible to put on paper the principles that both parties would subscribe to. This would allow them, under those principles, to enter elections. It was a fascinating experience. I became, together with a fellow named Peter Sole, a Progressive Party member, the secretary of the commission. The secretary organized who would give evidence, et cetera.

Q: Your involvement in the Marie Commission got some acknowledgement from the U.S. government and they were aware and invited you. Were you the creator?

I was instrumental. Just Peter Sole and me. I was the United Party and he was the Progressive. We were unified in our belief that we should have a combined opposition to the Nationalist Party. Fragmented opposition was just a waste of energy.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

LLB (Bachelor of Law), Stellenbosch University 1960

Legal Career

Pretoria, South Africa—Senior Partner Attorney Early 1960s

Political Career

South Africa—Parliament Candidate for United Party 1974

South Africa—Member of the Marie Commission 1977