John F. Kennedy inspired generations of Americans toward a life of service starting with a few impromptu lines not many people know about. Months before he called on his fellow Americans to “Ask not…” during his inaugural address, Kennedy riffed with students at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, on October 14, 1960. It was 2 a.m., yet thousands had waited several hours to greet the candidate. “How many of you who are going to be doctors, are willing to spend your days in Ghana?” he asked. “Technicians or engineers: how many of you are willing to work in the Foreign Service and spend your lives traveling around the world? On your willingness to do that, not merely to serve one year or two years in the service, but on your willingness to contribute part of your life to this country, I think will depend the answer whether a free society can compete. I think it can. And I think Americans are willing to contribute. But the effort must be far greater than we’ve ever made in the past.”

Within a year, Peace Corps volunteers would travel to Ghana, Colombia, Tanganyika, and elsewhere, including the Philippines, where 128 volunteers arrived in October 1961 to serve as teachers and teachers’ assistants. Among this cohort were two future U.S. Ambassadors: Parker W. Borg, U.S. Ambassador to Mali and Iceland, and Brenda Brown Schoonover, U.S. Ambassador to Togo. This—laying the groundwork to develop a cadre of professional diplomats steeped in cultural understanding at the most basic level—fulfilled Kennedy’s ultimate goal in establishing the Peace Corps. Weeks after addressing the crowd outside the Michigan Union, Kennedy expanded on his vision during a speech at San Francisco’s Cow Palace: “The key arm of our Foreign Service abroad are the ambassadors and members of our missions. Too many have been chosen—who are ill equipped and ill briefed.… Men who lack compassion for the needy here in the United States were sent abroad to represent us in countries which were marked by disease and poverty and illiteracy and ignorance, and they did not identify us with those causes and the fight against them.… How can they compete with Communist emissaries long trained and dedicated and committed to the cause of extending communism in those countries? I therefore propose that our inadequate efforts in this area be supplemented by a peace corps of talented young men and women, willing and able to serve their country in this fashion for 3 years as an alternative or as a supplement to peacetime selective service.…”

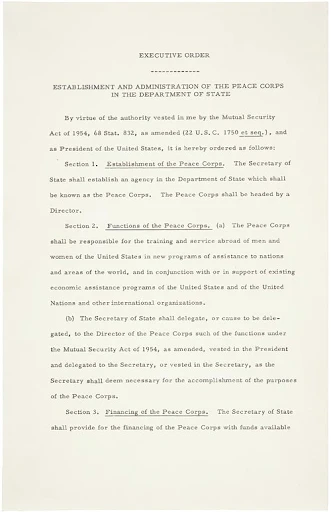

Kennedy went on to win by 120,000 votes, defeating Richard M. Nixon to become the thirty-fifth president of the United States. By March, he would sign an executive order establishing the Peace Corps within the Department of State. Six decades later, some seventy U.S. ambassadors have come up through the foreign affairs community after getting their start with the Peace Corps.

Below Parker Borg reflects on his views of Kennedy, the Peace Corps, and lessons from his two years in Camarines Norte, a southern province on the island of Luzon twelve hours by road from Manila. “They wanted to have a soccer team at the elementary school, but there was no one to be the soccer coach. I hadn’t a clue how to play soccer, so I acquired a book and read the rules on soccer, and I became the soccer coach.

Our team went on and won the district championship. To me it showed that with a little bit of interest and dedication you can do a lot of things.”

Brenda Brown Schoonover’s oral history transcript is maintained at the JFK Library. She discusses her impressions of the training, her fellow volunteers, and her counterparts. On the significance of the experience with regards to cross-cultural understanding, Schoonover says, “It was very positive and I think I learned a lot from the Philippines and the Philippines culture because they were so caring, so patient, and I think that that exposure has really helped me throughout my adult life and my career in learning how to listen and not jump in immediately with your own opinion, thinking that everything that’s American is the best and that we’re always right. And they had a gentle way of reminding you that that wasn’t so at all times.”

As for JFK’s visit to the University of Michigan, readers might enjoy hearing the students’ reaction near the end of Kennedy’s remarks in this short video.

Parker W. Borg’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy, initial interview date, August 12, 2002. Read his full oral history HERE.

Brenda Brown Schoonover’s interview was conducted by Ivan C. Browning, on April 6, 2018. Read her full oral history HERE.

Drafted by Ben East as part of a special collection examining how Peace Corps service impacted the careers of some seventy returned volunteers and former Peace Corps staff who went on to serve as U.S. ambassadors.

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

AMBASSADOR PARKER W. BORG

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education / Background

- A.B. Dartmouth College 1961

- M.P.A. Cornell University 1965

- Peace Corps

- Philippines AID Mission

Joined the Foreign Service 1965

- Ambassador to Mali 1981–1984

- Ambassador to Iceland 1993–1996

Q: By the way, the Kennedy campaign, Nixon-Kennedy campaign, was going while you were in college. How did that…?

BORG: I followed it very, very closely. I began listening to campaigns in detail, I remember, in 1948, and it was largely because Humphrey, our mayor in Minneapolis, went down to the Democratic Convention and talked about civil rights. I became a Humphrey enthusiast from that point. I thought this man has the right idea about lots of things. My family was always in the Republican camp. I was more skeptical. I followed the Nixon-Kennedy campaign very closely and was leaning particularly towards Kennedy but got very upset about his comments on Quemoy and Matsu in the 1960 election especially how these might be the sorts of things that we would consider going to war over. I thought this man is just too far out, that is totally irresponsible, and so I voted for Nixon.

Q: It’s interesting because so many of our compatriots got caught up in this campaign and didn’t get onto sort of the particulars, which you did. When one thinks about it, two presidential candidates debating over these two bloody little islands in the Straits of Formosa… Well, what happened to you then? I guess in the spring of ’61 you went down…

BORG: I was very turned on by Kennedy’s inaugural speech. I thought, wow, I didn’t vote for this man but he’s saying the sorts of things, he had the rhetoric, that inspired me. So I went down to Washington, went into the Peace Corps interim headquarters, and was told that the Peace Corps had no interest in me because I was from an Ivy League school.

I also took the Foreign Service test that year, and I passed it in Russian language but missed, was about two points under, for the other things.

Q: Being told that you were persona non grata for being an Ivy Leaguer must have turned you way off, didn’t it?

BORG: No, it turned me to figuring out what it was that I might be. I was very intent on joining the Peace Corps and so I checked on what were the first programs that they were going to be starting. There were programs in Tanzania, Ghana, Santa Lucia in the Philippines. They were all technical ones except the Philippines. The Philippines was going to be an education program. So when I filled out my Peace Corps application, I said that I wanted to be a teacher and that I was really interested in a career in teaching. To my surprise, I was selected despite my lack of teaching background but, I guess, because I had indicated an interest. So I was selected in the summer of ’61 when the first groups were being chosen for the Peace Corps. My parents couldn’t believe I finished college, came home, sat around, did nothing and talked about nothing but the fact that I was going to be joining the Peace Corps. They said, you know, “You’ve got to get serious now. You’ve got to find a job out there. We paid all this money for you to go to an expensive college all these years. You’ve got to do something now. You can’t waste your time and waste your money.” But I was intent, and it came through that I had been selected for the first group to go to the Philippines.

Q: Let’s talk about the group when you found it. How did you find it? Was it as non-Ivy League as they wished.

BORG: No, it was a mixed bag. It had people from all sorts of different schools. I knew best the people whose names in alphabet were right next to mine because everything was done alphabetically and we ended up living in the same community. One of the guys went to Yale where he’d been in the divinity school. He was an atheist. Another guy had been to UCLA where he was doing theater, and the third one was studying agriculture at the University of Kansas, so almost nobody had educational backgrounds.

Q: While you were doing this, any impressions of Philippine culture?

BORG: I was really excited about learning the Filipino language so that I could sit in the bus on the way to and from my school and hear the revolutionary thoughts that were going through people’s heads.

I was anxious to hear them talk about the need for land reform and the need to overthrow a corrupt government, all of the sort of intrigue that one imagines goes on in the third world. I never learned the language really well but I learned it well enough that I could listen in on conversations, and I heard the men talking about fixing their bicycles, fixing their cars, and local sports teams, and I listened to the women talk about babies and gossip and things that women talk about. I never heard a singular revolutionary thought from anybody.

Q: What about the students? How did you find the kids?

BORG: The town where I was working was a huge industrial overflow city. There was a steel mill in the next town. The kids whose parents worked in the steel mill lived in the next town, but the kids who lived in my town were the kids whose parents maybe serviced the steel mill. They ran the restaurants, there were a couple houses of ill repute, and there was a doctor, a dentist. It was a small town that lived on fishing and I’m not sure what else. In high school some of the boys were much older because they had had a very poor education, so I had 15- or 16-year-olds who were still in sixth grade. I enjoyed working with some of these older kids, trying to get them organized. They wanted to have a soccer team at the elementary school, but there was no one to be the soccer coach. I hadn’t a clue how to play soccer, so I acquired a book and read the rules on soccer, and I became the soccer coach. Our team went on and won the district championship. To me it showed that with a little bit of interest and dedication you can do a lot of things.

Q: By the time you were getting close to leaving in ’63, were you figuring out whither?

BORG: No, I had pretty much decided — maybe the first year that I was there — that what I wanted to do when I left was go to graduate school. I wanted to go to Cornell because it had a Southeast Asia program. I had a summer project my first year. Schools were only operating for eight, nine or 10 months a year or something like that, so I had two months off. I took my summer project and I went up to AID, to the head of AID, and asked about working for free in the office. So I was an AID intern for the summer, and that was where I first met Foreign Service Officers. I was appalled. I thought, oh, my God, what stupid jobs these people have. I became good friends with someone, who remains a good friend, and he told me about how they really went out and they were teaching Filipinos how to do square dancing on the weekends and once a week they would square dance and they went to the yacht club on a certain night and all these things. This whole thing just sounded so tedious to me. The people seemed to be perfectly nice, but the jobs that they had, I couldn’t imagine wanting to do any of this sort of work. Q: This was from the embassy, not from AID? BORG: Well, the embassy was right across the street from AID. These were embassy people. There were more embassy people my age than there were AID people. Q: The embassy lived pretty much in a compound there? 19 BORG: No. There was a compound where some people lived, but a lot of other people lived in various apartments around town. In fact, I stayed with a Foreign Service Officer. He put a sign up in the Peace Corps office saying, “Anybody who’s looking for a place to stay, give me a call.” So I called him and he said, “What nights are you going to be here?” and I said, “I’m going to be here for the next six weeks.” He said, “Oh, no, I’m talking about just a couple of nights,” but he relented, and so I moved in and stayed at his place for six weeks. So I got sort of an inside look at the Foreign Service. Q: What was there about it? It wasn’t connected or wasn’t doing what you were thinking? BORG: It didn’t seem to have any connection with the country as I saw it. They were mostly younger officers doing visa work and participating in what I thought was the most frivolous sort of life, traveling relatively little outside of the capital, going out on their sailboats on the weekends, and sort of living an American life in this foreign country. By contrast, I was very much into the culture.

Q: In many ways this is, of course, the typical reaction of the Peace Corps volunteers towards embassies. We’re out in the boondocks and we’re living the real life, and you’re up here in the capital and you don’t know the country. I think this is duplicated almost everywhere.

BORG: That’s right, yes. Q: What were you doing with AID? BORG: I think I may have been the post project to the head of AID. Somehow I got an appointment with the head of AID, who was astonished that somebody from the Peace Corps wanted to have anything to do with him. I proposed that I do a study for them of all the other aid that was going on in the country. I said, “Do you know who’s doing what?” and they said, “No, we haven’t a clue who is doing what other kinds of assistance in the Philippines.” So I spent the summer going around to all of the other assistance organizations, both government and NGOs, to find out what kind of things they were doing, how much money they were spending, and where they were focusing. It turned into a report that the AID mission thought was sufficiently interesting that they assigned somebody from the AID mission to continue this project and keep it going. They did it for a number of years.

In addition to serving as Ambassador to Mali (1981-1984) and Iceland (1993-1996), Parker W. Borg also served as Deputy Director for Counter-terrorism, Acting Coordinator for International Telecommunications and Information Policy, PDAS for Counter Narcotics, Director of West African Affairs and Principal Officer at the US Consulate in Lubumbashi, Zaire. Ambassador Borg held staff jobs in the Department, including as Special Assistant to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, Special Assistant to the Director General of the Foreign Service, and line officer on the Secretariat Staff. He served three Vietnam assignments and served in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. His post-State Department jobs included the national security project at the Center for International Policy; teaching in the International Relations Department at the American University of Rome; and running a graduate seminar on diplomacy at the American Graduate School of International Relations in Paris.

AMBASSADOR BRENDA BROWN SCHOONOVER

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education / Background

- B.A. Morgan State College 1961

- Peace Corps

Joined the Foreign Service 1982

- Ambassador to Togo 1997–2000

Q: How did you become aware of the Peace Corps?

SCHOONOVER: I thought it was part of Kennedy’s campaign. And it was being touted that it was going to happen even before he became president and I took the exam my first opportunity. That was probably June of 1961, and I had a telegram. Well, I wanted to go to Africa and I told you why I want to go to Africa because I met all these students and because I’d seen those two documentaries which inspired me. But then I got a telegram offering me the Philippines. And the telegram arrived 12 hours after I had taken the Peace Corps exam.

Q: They must have liked your performance on the exam.

SCHOONOVER: I think they were trying to get the program of the Peace Corps Act, which had just been signed and in March, I think so. I think they were trying to get the program off the ground. But I was certainly thrilled and looked up on the map to find out where the Philippines was. And, you know, and that’s.

Q: They must have liked your performance on the exam.

SCHOONOVER: I think they were trying to get the program of the Peace Corps Act, which had just been signed and in March, I think so. I think they were trying to get the program off the ground. But I was certainly thrilled and looked up on the map to find out where the Philippines was.

![First Peace Corps Director R. Sargent Shriver (center) calls on President Carlos P. Garcia [left] on board the RPS Lapu-Lapu in Manila, Philippines, May 23, 1961. Introducing him to the President is U.S. Ambassador John D. Hickerson [right]. International Cooperation Administration (ICA). R. Sargent Shriver Personal Papers. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston](https://adst.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Schoonover-3.webp)

And, you know, and that’s. Back to my mom, I mean, she let me integrate that school. She could have said, I don’t want you going off to the Philippines. You know, she was very open and letting me soar as far as I could.

Q: So she felt OK about losing her little girl for two years?

SCHOONOVER: Well, about 20 years later, after I’ve been a Peace Corps volunteer and was back home, my mom said, you know, when you were offered the Philippines, I didn’t realize just how far it was and when I took you to the airport, I saw you off and she was with a neighbor, went with her, and she said, I promised I would not cry. I didn’t want you to see the last vision that had the last vision of me crying. So I kept my cool until you got on the plane. And then I fell apart. And my friend and I were walking back to the car and we went by this airport bar and the bartender came out and said, bring that lady in, she needs a drink. But you know, she had the courage and the foresight not to worry me about that, not to even tell me until I said, you know, I was probably 20 years later.

Q: That is amazing. Do you remember how you felt when you received that telegram?

SCHOONOVER: I was almost I wasn’t sure whether it was real. I mean, 12 hours, and then everything happened very quickly. We went to State College University, Pennsylvania State College, for training in July 1961, so. So that didn’t give us much time to think. I was too busy planning. And then people were saying, well, why are you going off to volunteer? What about your career? What about your, what about a decent salary? What about buying a house? What about car? What about an apartment? And I said, no, I want to do this and I can do those other things later.

Q: So when you got the telegram. You were ready to accept the invitation. Did you have any misgivings?

SCHOONOVER: No misgivings, none. No. I knew this was very special.

Q: Certainly blazing a trail.

SCHOONOVER: Yes.

Q: Excellent. So you went off to training and where was that again?

SCHOONOVER: There’s a state University of Pennsylvania State College, State College, Pennsylvania, and that was about six weeks of training, as I recall.

Q: Ok? And all of the members of the group that you mentioned, are how many?

SCHOONOVER: There were 100 if my memory serves me correctly. They were 165 of us that went into training and 128 of us made it all through. And others who left. I’m not sure how many left on their own volition or others who were not selected. We had lots of tests, you know, kind of like, I guess, the kind of test you take to get into graduate school and then we had interviews, so we had to pass a security background. And that might have been a factor for some people. And we did have an interview with the psychiatrist.

Q: So what kind of facilities were used in this in the training?

SCHOONOVER: Well, it was the university in the summertime, so we were in student dormitories and I had a dorm room with another volunteer who was in training. Ellen Brindle was her name. Wonderful lady.

Q: And when you trained where it was in a classroom environment?

SCHOONOVER: It was in a classroom environment and was mainly focusing on the culture of the Philippines, the history and then some of the methods of teaching, but the most significant part of the training was on the cultural sensitivity part. And there was a Professor Guthrie who was so perceptive and so enlightening on how each culture basically has the same values, but the priority list of those values can vary. For example, we in the U.S. like to think that honesty is at the top of our list, whereas in some Asian cultures, shame is often at the top of the list. So being shamed is less important, to be honest, than to make sure you don’t shame somebody. That kind of thing. And that, as brash young Americans, that was something we really needed to learn because we know we were just out of college, most of us, and we wanted to express our opinions and tell it like it is. And that didn’t always work. And we had to learn. I think some of those lessons from that cultural training have helped me throughout my life. And certainly as a diplomat, I learned a lot from that.

In addition to serving as U.S. Ambassador to Togo, Brenda Brown Schoonover is past president of American Diplomacy Publishers and has been a board member for over 15 years. A retired Foreign Service Officer, she accompanied her late husband, Richard Schoonover, on his tours with the United States Information Agency (USIA) to Nigeria and Tunisia. The couple had tandem assignments in the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Tunisia, and Belgium. She was Diplomat-in-Resident at the University of North Carolina (UNC) followed by an assignment to the U.S. Embassy in Belgium as Deputy Chief of Mission. She held staff positions at the Peace Corps Headquarters in Washington, D.C and in Tanzania. Among her advisory and board of director roles, Schoonover serves on the N.C. Advisory Committee to U.S. Global Leadership Coalition, Med Aditus, and Carolina Friends of the Foreign Service. She completed her tenure as president of the UNC Woman’s Club in June 2020.