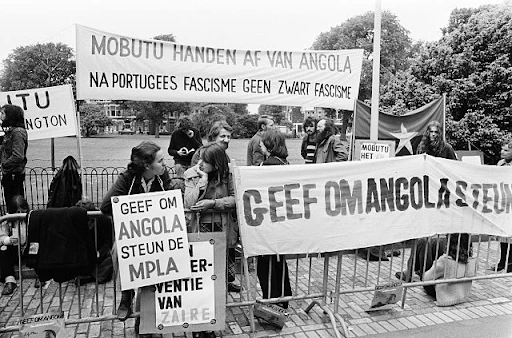

After World War II, the idea of imperial colonization became increasingly stigmatized. Decolonization in Africa sometimes resulted in political power vacuums. Multiple groups and individuals, both inside and outside the continent, sought to reclaim this power as their own. For example, the departure of the Portuguese in Angola also fuelled guerilla warfare across the newfound state during the transition of power.

During this period, the U.S. geopolitical interest in Africa was limited, prioritizing American concerns around containment of the USSR. The fighting waged against the Portuguese by Angolan liberation groups fell outside the main scope of U.S. involvement in Angola. After serving in Vietnam, Foreign Service Officer Edward Fugit grew familiar with this obscure form of warfare. Fugit took special interest in the emerging conflicts in Angola, placing himself in the midst of these hostilities in order to gain a deeper understanding of the tensions within the state.

Fugit’s work did not stop in Angola. In 1983, after working in Africa for approximately ten years, Fugit was offered an assignment in South Africa. Once again, Fugit found himself at the center of a seemingly domestic conflict with numerous foreign players. Only, this time, U.S. involvement extended far beyond concerns of Soviet influences. The Anti-Apartheid movement sparked tensions across American political systems, eventually leading to Congress overturning President Regan’s veto of the Anti-Apartheid Act in 1986.

Follow Fugit’s journey across Africa and the Middle East in his complete oral history HERE.

Edward Fugit’s interview was conducted by David Reuther on January 25, 2021.

For more Moments on the end of Apartheid in South Africa click HERE.

Drafted by Jenna Alexander

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“I decided to make myself the U.S. expert on this obscure guerilla war.”

From Vietnam to Angola—An Expert on Guerilla Warfare:

There was a low-level guerilla war between three different liberation groups in Angola and the Portuguese. There was also a war in Mozambique with one large group fighting the Portuguese. Then in Guinea Bissau there was another group also fighting the Portuguese. These were all totally separate from each other but they all drained Portuguese resources….

I realized that no one paid much interest to the guerilla conflicts. I thought this is something I can understand. It was only three and a half years since I had left Vietnam.

I understand small unit warfare, so I decided to make myself the U.S. expert on this obscure guerilla war. I contacted the Portuguese military High Command in Luanda and developed a couple of contacts at the Lieutenant Colonel level. I informed them that I am planning to travel around and visit the different zones where the fighting is going on…. I went out to the contested areas in the interior where fighting was going on. One was up in the north, which was between Luanda and Zaire. And the group there was the FNLA [National Liberation Front of Angola], which was representative of the ethnic group north of Luanda….

I would travel, and I would see U.S. missionaries. There were a lot of American missionaries, either American citizens or other national citizens that were paid for by American churches. And part of my job was to stay in touch with the Americans who lived out there—providing passport services, reports of birth and death, etc. I tried to visit everybody at least once a year in each of these different mission stations. I quickly learned that what I wanted to do was go see the Protestants in mid-morning and mid-afternoon and go see the Catholics for lunch and dinner because the Catholics will offer you liquor whereas the Protestant missionaries are tea totalers. I would take some bottles of scotch with me, and sit down with some Catholic priests and doctors or whatever, and have some drinks and dinner and really get a feeling what was going on, amongst the people of the countryside.

“One day in 1974 the Portuguese said to me, “Look, we’re sending a chopper out to see Savimbi, the head of UNITA, you want to go out?” I didn’t ask Washington; I just went….”

The Liberation of Angola—The UNITA Movement:

The Portuguese didn’t want any more fighting, they wanted to hand power over to somebody. Their plan was that they would organize a peace conference of the three liberation movements and themselves and work out a deal handing it over to a coalition government. The three groups in Angola were of different ethnic backgrounds and did not trust each other. They all thought they should rule the country. I was trying to figure out more about the capabilities of these organizations. I had seen them from the Portuguese perspective, but I had not managed to talk to them as they had no offices in Luanda.

One day in 1974 the Portuguese said to me, “Look, we’re sending a chopper out to see Savimbi, the head of UNITA, you want to go out?” I didn’t ask Washington; I just went, and we flew out there and we circled. I’m very adept from my time in helicopters in Vietnam at judging military positions from the air and figuring out where the enemy is. I looked down and I didn’t see anything. When we landed there was a large military base camp. UNITA had done a very professional job of camouflaging their operation. Now, what does that mean? For these groups in Angola that was more than I had expected.

UNITA had gun positions; everything was set up the way a good military would organize itself. And I was rather impressed when I walked around and I got to just look at things, figure out what they’re up to.

I talked to some of the officers, and they were intelligent. Almost all of them had been educated in missionary schools because they came from that part of the country where there was no government presence to speak of.

On another occasion I drove down to the second biggest city in Angola, which is now called Huambo. I knew this was the heart of UNITA support. As I’m driving, I see a whole bunch of young men and they’re standing, waiting in line going into this building, so I stop and look at it, and the building was the local UNITA headquarters. These were young men signing up to fight. This was one of the indicators to me that Savimbi and UNITA had some real popular support. There were offices in Huambo from the other two groups but nothing was going on there.

“Angola/Ethiopia/Mozambique were not important to Moscow any more than they were important to Kissinger, rather they were a pawn in the great power competition.”

A Pawn In Someone Else’s Game—The Manipulation of Africa:

When I first started in August, to me, this was an African problem, as it was to everybody in the African Bureau. It’s another civil war in Africa, not uncommon. Even after I got read in early September to the covert program and when I started taking notes for Kissinger and talking to him. It didn’t occur to me immediately what his thinking process was, and this is critical to everything that happens. He did not see it as an African problem. He saw it as a containment issue against the USSR.

The background to his thinking is critical. It became clear to me over the next six, seven weeks that this happened six months after the fall of Saigon. It happened a year after Nixon left office, the U.S. presidency is in disarray. The U.S. militarily and politically is probably its weakest point, post-World War Two. There was the Congress that had just been elected, was very much very liberal, and they weren’t supportive of military actions or clandestine operations. That was to be proved out in about two months. But Kissinger saw this in terms of our relationship with Moscow and the U.S. containment policy. Because to him it wasn’t just Angola. I was looking at it as just Angola. But no, it also was Ethiopia. There was a takeover there by pro-Moscow forces that threatened our bases there. Then you have Mozambique, which is now independent and taking a very pro-Moscow line.

These events were seen by Kissinger as part of an attempt by the Soviets, who sensed a weakness in Washington. He was convinced, and I began to agree, that’s what their effort was. Moscow was trying to leap over the barrier of U.S. containment by undermining the U.S. position wherever they could. Angola/Ethiopia/Mozambique were not important to Moscow any more than they were important to Kissinger, rather they were a pawn in the great power competition. And that was to play out. I realized this is more than just an African civil war. And this is an issue Kissinger wants to stop the Soviet Union from being able to use to break out of containment. So that affected how I addressed these issues because he wanted something done about it.

“All the police drive away. I’m looking down the street about, oh, four blocks away. And here’s this mob coming towards us.”

Mob Mentality—Heightened Tensions Between the U.S. and Zimbabwe:

The president of Mozambique, Samora Machel, was killed in an airplane crash on the 19th of October. And he was flying around Southern Africa in his airplane, which is a Russian plane, I believe. Anyway, it had an engine malfunction, and it crashed in the mountains. So, the first word that gets out about it is people say, “Oh, the Americans had to do it. The Americans did it.” …. The police notified us that there were hundreds of demonstrators coming our way from the University of Zimbabwe….

I see this mob is coming down the street…. I’m talking with a police captain who’s in charge of—they had about five or six squad cars there. And suddenly, he gets something over his radio. And he says, “Mr. Fugit, I have to leave.” And he won’t speak to me. He gets in his car. All the police drive away. I’m looking down the street about, oh, four blocks away. And here’s this mob coming towards us….

Suddenly, we don’t have protection….

Everybody’s burning what we have to burn. But if they get in the building, at what point do you use protective fire? Because if you do, the danger is that the mob is going to turn on you and basically kill everybody. There is no good answer as to what you do in those circumstances. If they’re coming into the building. So anyway, we’re prepared for it. They throw a bunch of rocks and one comes through the window…. So, that’s the first four months on the job. Relations with Zimbabwe weren’t good. And that didn’t help whatsoever.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in International Relations, University of Vermont 1961–1965

MA in Foreign Service, Georgetown University 1965–1967

Joined the Foreign Service 1970

Angola—Foreign Service Officer 1973–1975

Washington D.C., United States—Angolan Desk Officer 1975–1976

Durban, South Africa—Deputy Officer 1976–1979

South Africa—Desk Officer 1983–1985