Annually, as a sign of respect, Americans observe a moment of silence at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month, November. At that moment in 1918, the fighting ended on the Western front, and on November 11, 1921, the United States buried an unknown American soldier who died in World War I in Arlington National Cemetery. Around the same time, several other allied nations buried unknown soldiers in their highest places of honor. This uniformity of gratitude marked the universal recognition of soldiers and their sacrifices during the “war to end all wars.”

In 1926, a Congressional resolution recognized November 11 as Armistice Day, and on May 13, 1938, legislation signed by President Franklin Roosevelt made it a national holiday.

Contextually, 1938 was the year after the Japanese invasion of China and the year before World War II broke out in Europe. The war devastated much of the world and led to millions of deaths.

Two years after World War II, a veteran, Raymond Weeks, organized National Veterans Day to honor all veterans. This event on November 11, 1947, in Birmingham, Alabama, marked the first celebration of Veterans Day. In 1954, President Eisenhower signed the bill which renamed Armistice Day as Veterans Day to honor all veterans of World War I, World War II, and the Korean War. Later, Veterans Day also included veterans from the Vietnam War.

In honor of Veterans Day, ADST has compiled anecdotes of American veterans who became diplomats. While they served in uniform, many future American diplomats learned new languages, gained firsthand experience working in other cultures, and prepared for the Foreign Service examinations to open new chapters in their lives of service.

Drafted by Aminata Diallo

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

World War I

EARL PACKER

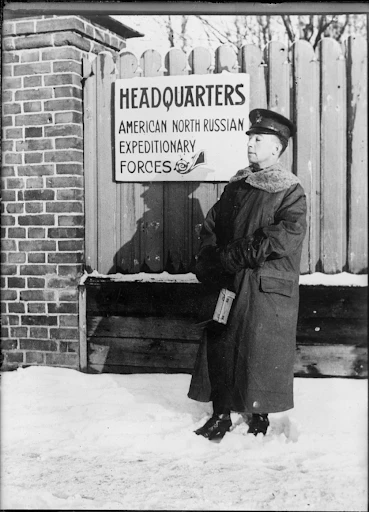

Russia—U.S. Army 1917–1919

“We had come into the war, and it was considered desirable—from a military point of view . . . to somehow keep Russia active as long as possible in the war.”

In 1915, Earl Packer left Utah to become a clerk in Washington, DC. Through the State Department, he learned there were opportunities for clerks to serve in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) and later Vologda during the Bolshevik Revolution. During his time at the US Embassy in Vologda, Packer was commissioned as an infantry first lieutenant (and later named an assistant military attaché) and joined the staff—located in Archangel—of the American Military Mission to Russia. After the war, Parker returned to Washington, and he was offered a position in the Department of State in 1921. As a Foreign Service Officer, he served in Riga, Tallinn, Budapest, Dublin, Turkey, Rangoon, and Tunis; he retired in 1947.

Mission to Russia:

Q: Why did we have a military mission?

PACKER: We had come into the war, and it was considered desirable—from a military point of view—to have this mission created. It was called The American Military Mission to Russia. The job of being a clerk in the military mission came up, and it led—in due course—to my being commissioned as a first lieutenant of infantry, United States National Army (USNA). From Vologda, as things progressed badly for Russia—on the western front—the decision of the allies was that intervention should occur, with a view to preventing the deterioration of Russia, as an ally of the Western powers, against Germany. A military expedition was sent into Archangel, and the embassy moved from Vologda to Archangel.

Q: Now, the U.S. was not fighting against Germany in Russia, was it? What was the purpose of the mission?

PACKER: The purpose of the mission—looking at it from the point of view of Washington—could only have been to somehow keep Russia active as long as possible in the war. But the military mission actually wasn’t—in my opinion—a great success, because the Russian armed forces were not able to prevent the creation of a Soviet government, which put the Kerensky government out of commission . . . .

Read Earl Packer’s full oral history HERE (this excerpt can be found on pages 2–4).

******************************************************************************

World War II

LEWIS WESLEY BOWDEN

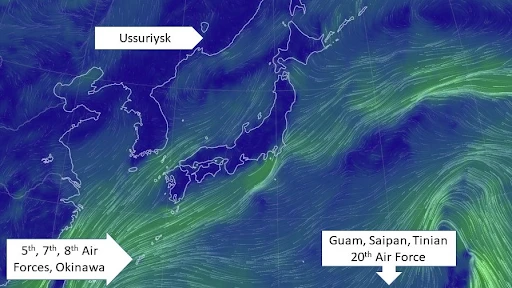

Ussuriysk, Russia—U.S. Navy 1942–45

“Since I was the youngest officer in the crew, the captain designated me as the carrier to transport classified documents between our mission and the Assistant Naval Attaché’s office at Vladivostok.”

Lewis Wesley Bowden, born in Oklahoma and raised in Kansas, served in the Navy in World War II. After training and commissioning as an ensign, he attended the Naval Intelligence School in New York. In 1945, he joined a secret Navy/Air Force mission to the USSR to set up a weather station near Ussuriysk to provide weather information for U.S. air and naval operations against Japan.

Bowden became familiar with the Foreign Service when he carried classified documents to the American Consulate General in Vladivostok. After his time in the Navy, Bowden changed the course of his studies, and he began work in the State Department in 1950. He entered the Foreign Service in 1952 and worked overseas in Belgrade, Bern, Moscow, Brasília, and Saudi Arabia.

Observing the Weather:

Q: That was in World War II.

BOWDEN: Yes. I spent a year at Yale in the V-12 program and then went to midshipman school where I graduated as an ensign in October/November 1944. Then I went to Naval Intelligence School in New York. In the summer I was assigned to a special detail Naval/Air Force combined secret mission to the USSR to set up a weather station near the city of Ussuriysk to provide weather information for air and naval operations against Japan.

Q: This is the eastern part of the Soviet Union—Ussuriysk?

BOWDEN: The importance of this episode is probably two-fold. One, it was my first experience with Russia. As a matter of fact I spent my 21st birthday there. All these things made a tremendous impression on me, particularly because our relations in general deteriorated. This deterioration was reflected specifically in the attitude of the local military people toward our mission. Things got more and more difficult as time went along.

The second thing is that I became acquainted with something called the Foreign Service while living among this mission. Since I was the youngest officer in the crew, the captain designated me as the carrier to transport classified documents between our mission and the Assistant Naval Attaché’s office at Vladivostok . . . .

Read Lewis Wesley Bowden’s full oral history HERE (see pages 1-2 for this excerpt).

******************************************************************************

World War II

AMBASSADOR MARSHALL GREEN

Washington, DC—U.S. Navy 1941–1945

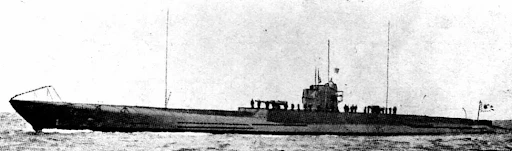

“We had never heard of the ‘Shiminoseki-7 Maru,’ but we could immediately deduce from its call sign the size of the ship and whether it was an oiler or freighter.”

Marshall Green was born and raised in Massachusetts. As a fresh graduate of Yale University in 1939, he became a private secretary to Joseph C. Grew, the U.S. Ambassador in Tokyo.

Initially, Green knew little about Japan and its empire, but travel with Ambassador Grew allowed him to observe Japanese rule in Korea and Manchuria. Entering the Navy after the outset of the war, he learned Japanese, and at the Office of Naval Intelligence he translated captured Japanese documents. In 1945, Lieutenant Green left the Navy and entered the Foreign Service. His initial task in the Department was to get ex-Foreign Service Officers—those who had become naval officers—to return to the Foreign Service. Initially serving in Washington and Korea, Green was twice an Ambassador—to Indonesia and Australia.

Translating Japanese Documents:

GREEN: …I was not interpreting. I was translating—lots and lots of documents, some of them fascinating. I was once given documents we took out of the I-1 submarine sunk off Guadalcanal. This was a bunch of oil-soaked documents flown to Washington, to the Naval laboratories in Anacostia, MD. I worked for several days and translated this stuff. It was absolutely fascinating. The Chief Engineer of the I-1 submarine kept careful records of all of the ships that were being built in Japan for the submarine fleet, both the coastal and seagoing types. All the names were listed down one side of the document followed by the specifications of each ship, both those that were afloat and those that were being built—and where they were being built: Ominato, Jure, Yokosuka, and Sasebo.

So on this great, pullout sheet, with a minimum amount of effort, I was able to get all of the details of the Japanese submarine fleet. We put out two “Fleet Bulletins” on the basis of that. That’s one thing that I was able to accomplish. It was very typical of my whole career. I was lucky, just lucky. Another accomplishment was in communications intelligence, when I got the idea that the “call signals” new ships were using related to their standardized sizes and uses and to where the Japanese were building them. Therefore, we were able to nail down, merely from call signs, roughly what kinds of ships they were.

Read Marshall Green’s full oral history HERE. Read more about Green’s translating assignment on page 18.

******************************************************************************

The Korean War

CHARLES STUART KENNEDY

Korea, Japan, Germany—U.S. Air Force 1950–1954

“You didn’t screw around in a military organization, you understood that you were part of an organization, and you were supposed to do certain things.”

Charles Stuart Kennedy, born in Chicago and raised in Annapolis, graduated from Williams the month the Korean War broke out. He initially joined the Massachusetts National Guard, but wanting active service, he enlisted in the Air Force. During his education, he had learned some Latin, Spanish, and French, but the Air Force sent him to study Russian. Kennedy monitored the Soviet Air Force in Korea, Japan, and Germany. In 1954, he was discharged as an Airman First Class. Becoming a Consular Officer in 1955, Kennedy’s assignments included Frankfurt, Dhahran, Belgrade, Saigon, Athens, Seoul, and Naples.

Monitoring Air Fights:

KENNEDY: . . . When asked if I had any language training, I told the sergeant that I had taken three years of Latin, three years of French, and two years of Spanish in prep school. I said, “But sergeant, I did terribly.” He said, “That don’t make no difference, you’re going to the Army language school,” and I did, where I took Russian. When I went to Korea, in 1952 I sat on a radio set and monitored the Soviet air force that was fighting the American air force. It’s still something not talked about very much, but we were fighting a full-scale air war against the Soviets. I was in Japan only for a while where I was doing the same monitoring, and then I went to Germany because I came back to the U.S., my mother was ill, and then they sent me off to Germany. So I was monitoring Soviet air force radio nets in Germany.

There was nothing more fun than being a young service man in Japan and Germany. Korea was a little something different. But I must say we lived in a relatively repressed time . . . .

Read this part of Charles Stuart Kennedy’s oral history HERE. Visit pages 6–7 to read more about Kennedy’s missions.

******************************************************************************

The Cold War

AMBASSADOR JAMES G. LOWENSTEIN

The Mediterranean Sea—U.S. Navy 1953–1954

“We are going to be the first naval vessel since the war ended to call at a Yugoslav port.”

New Jersey native James G Lowenstein became a Foreign Service Staff Officer in 1952. From Paris he was sent to Sarajevo to observe and report on the distribution of relief supplies, discussions with Marshal Tito’s government, and “the landscape.” At the time, being a member of the Foreign Service did not exempt an individual from the draft, so he joined the Navy and became an officer in 1953. He was assigned to the USS Coral Sea, an aircraft carrier in the Mediterranean.

He separated in 1956 and was appointed as a Foreign Service Officer in 1957. He served in Colombo and Belgrade, and he became the U.S. Ambassador to Luxembourg.

Aboard the USS Coral Sea:

LOWENSTEIN: I had been aboard the Coral Sea three or four days when the Executive Officer of the ship called me in. I was a junior ensign on a ship of 4,000 officers and men. He said, “I have an assignment for you. We are going to be the first naval vessel since the war ended to call at a Yugoslav port. Not only that, we are going to have Tito aboard. We are going to take him out for a day. I want you to work with the Admiral’s aide and help him organize this thing.” I should have said that the Coral Sea was in the Sixth Fleet; the Coral Sea and the Roosevelt rotated.

…The Admiral led Tito on a review of the officers and men standing at attention. As they passed me, with my eyes fixed straight ahead, Ambassador Allen somehow spotted me and said, “Jim, what are you doing here?” I said, “Well, let me explain.” He said, “Well, come on. Why don’t you come along with us?” He said to the Admirals and Captains “Why this young man was this and that and the other thing and we worked together, etc.” And then he introduced me to Tito. He said something like this is the young man who helped save your country kind of thing, Tito nodded and said, “Yes, I know, I know, I know.”

…The Admiral’s aide came down and said, “You know who the other officers in the welcoming party were?” I said yes, and repeated their names and ranks. He said, “How many times do you think you saluted in the course of the day?” I didn’t really know the saluting protocol. So to make a long story short I was confined to my cabin for a week for not behaving properly.

Read James G. Lowenstein’s full oral history HERE. Interested in reading more about Lowenstein’s interaction with Tito and Ambassador Allen? Visit page 13.

******************************************************************************

The Cold War

LOUIS B. WARREN

Antigua, British West Indies—U.S. Navy 1964–1967

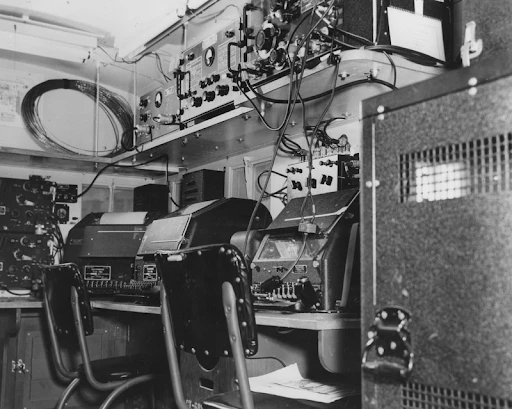

“We definitely tracked some Soviet submarines at very great lengths.”

Louis B Warren, raised in New York and New Jersey, served in the Navy during the Cold War. After graduating from Harvard, Warren attended the Navy’s Officer Candidate School and was commissioned as an ensign in 1964. After a year in the Fleet Sonar School in Key West, Florida, Warren was assigned to the Sound Surveillance Station in Antigua, tracking submarines. In 1967, Warren entered the Foreign Service and worked in the State Department as an information manager, creating codes to assist in the distribution of classified cables.

During his career, he served overseas in Vietnam, Oman, Algeria, Indonesia, and New Delhi and Mumbai in India.

Detecting Submarines:

WARREN: OK, I got out as an ensign in I think it was 1964. I then went to the Fleet Sonar School in Key West, Florida. Then I was a year—a little bit over a year—now this may be classified, maybe not. Basically I was assigned to the Sound Surveillance Station in Antigua, West Indies, where we really did track submarines, you know, picking up sounds on the deep sound channel access.

We definitely tracked some Soviet submarines at very great lengths. And we also started—and this spooked the guys up in Norfolk, which was our command center—because we were able to detect transiting U.S. nuclear submarines, which we weren’t supposed to be able to do. And that shocked the hell out of—because they said how did you guys detect these things?

Q: Well, how long did you do this?

WARREN: For about a year—about a year and yeah, a year and a few months. Then I was again, sent to Fleet Solar School and I was transferred as an anti-submarine warfare officer and boarded an old World War II Destroyer, USS Cony, DD-508.

Read Louis B. Warren’s full oral history HERE. Visit pages 9–10 to learn about Warren’s submarine tracking mission.

******************************************************************************

The Cold War

AMBASSADOR JAMES R. CHEEK

Germany—U.S. Army 1954–1956

“Because I had math and some college I got to go into field artillery and give fire direction which in those days was done with slide rules.”

After two years of junior college, Arkansas native and future Foreign Service Officer James R Cheek enlisted in the U.S. Army. He had heard about the GI bill’s benefits, especially for education. The war in Korea ended while he was training, so he spent two years in Germany as an artilleryman. After discharge, a period of service in the Army Reserve was required, and he received a rare direct commission as an officer, but he chose not to make the Army his career. He received degrees from Arkansas State Teachers College and American University, and he entered the Foreign Service in 1961. During his career he served in Brazil, Nicaragua, Uruguay, Santiago, London, Kathmandu, and Addis Ababa, and he became ambassador to both Sudan and Argentina.

Privileges of Education:

CHEEK: I served in the armed forces from 1954 to 1956. I went to Germany when we were still the army of occupation. In April of 1955 we became guests of the German Republic. We were no longer an occupier and in a whole new world. I was there and that’s why I have an occupation medal.

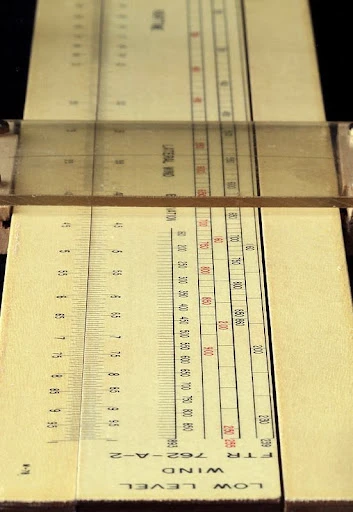

I had the two years of junior college. Of course that was a big deal in the military. It was unusual to have a draftee with some college…Because I had math and some college I got to go into field artillery and give fire direction which in those days was done with slide rules. Sighting, everything was done in your head. We were the brains of the battalion. Fire direction and control was a nice job. The data came into us, we decided where the guns should be set up. We entered the data and told the crews to fire the guns. Because I had some education. Otherwise, I’d have been down on the guns pulling the lanyard.

…On this day, just by chance, the commanding general of 4th Army descends on us. He helicoptered over, meets the brigadier and walks in. Here he sees a private first class doing the major’s/captain’s job. He looks really surprised. So in front of the brigadier he said, “You want to be an officer?” I said “Yes.” “Well, put your paperwork in and we will get you a commission.” …So I went back and filled out all this paperwork and sent it down to Fort Kirby and within a month I was a second lieutenant. At that point there was a temptation to actually make a career in the army. As a reserve officer you never really had a full tenure, they could call on you from time to time. I had visions of having a college degree.

Read James Richard Cheek’s full oral history HERE. Visit pages 11–13 to read about the advantages that Cheek received due to his educational background.

******************************************************************************

The Vietnam War

AMBASSADOR RONALD E. NEUMANN

Vietnam—U.S. Army 1970–1972

“These were people in nice, clean khaki uniforms and little pith helmets that came across from the north.”

Ronald E Neumann “made up his mind to join the Foreign Service” in the 10th grade in California, but “it just took a long time to get there.” He failed the Foreign Service examination the first time. He passed in 1967, but no class spaces were available. He had also volunteered for the Army, and service in the armed forces extended one’s candidacy for the Foreign Service. He was commissioned in the infantry after attending Officer Candidates School at Fort Dix, New Jersey. In 1970, he was a first lieutenant in the 5th Infantry Division just south of the demilitarized zone in Vietnam. After joining the Foreign Service in 1973, he served in Dakar, Bathurst, Tabriz, Sanaa, Abu Dhabi, and Baghdad. Neumann was three times an ambassador—to Algeria, Bahrain, and Afghanistan.

Threats in Vietnam:

NEUMANN: . . . the demilitarized zone was basically depopulated. The villages had either been bombed or they were in free fire zones so people had evacuated. It was an area where we wanted to keep supplies, and troops from moving down from North Vietnam into the South. It wasn’t an area of population protection or intermingled villages. In fact, the Viet Cong in our area were completely destroyed by the time I was up there. They were a tiny remnant of malaria-ridden folk. And they were really no threat to anybody.

Our threat was regular North Vietnamese Army Forces. This was not a guerilla war or an insurgency where I was. This was a regular war being fought with irregular tactics. Elsewhere I’m sure it was an insurgency but the enemy I fought were not to be confused with a popular movement. These were people in nice, clean khaki uniforms and little pith helmets that came across from the north. We weren’t allowed to shoot across the demilitarized line as a result of an arrangement that had been made sometime earlier. And so when we sat up at Con Thien we could watch the truck lights from the North Vietnamese Army delivering supplies down on the other side of the demilitarized zone. And in fact, there was one fight that my company got in, although I missed it because I was in the hospital probably with malaria, and they were reinforcing right across the DMZ.

Read Ronald E. Neumann’s full oral history HERE. For more information on this excerpt, visit pages 24–25.

******************************************************************************

The Vietnam War

DONALD BISHOP

Vietnam—U.S. Air Force 1969–1970

“CSC would then hit a base-wide alarm, and everyone would sprint from barracks or hangars to the shelters.”

Donald Bishop, raised in Connecticut and New Jersey, was commissioned in the Air Force in 1968. Less than a year later he was in the security police squadron defending Phu Cat Air Base in Vietnam against penetration of the perimeter by North Vietnamese sappers [demolition teams] and from standoff attacks.

His unit worked with the Korean regiment adjacent to the base, and he flew some “dawn patrol” missions as a “guy in back.” In the Air Force he also served a tour in Korea, and he taught at the Air Force Academy. In 1979, he became a Public Diplomacy officer in the Foreign Service, serving in Hong Kong, Taegu, Seoul, Taipei, Dhaka, Lagos, Abuja, Beijing, the Pentagon, and Kabul.

Rockets’ Red Glare:

BISHOP: For the rockets, the Wing depended on the vigilance of our security policemen on the perimeter—to see the rockets in mid-flight and to call in the news of “incoming” to Central Security Control, CSC. CSC would then hit a base-wide alarm, and everyone would sprint from barracks or hangars to the shelters until there was an “all clear.”

Whenever the base was hit, a team from the ROK 1st Infantry Regiment jumped into a jeep, came through the base gate at high speed, and went directly to the points of impact. Examining the craters, they could tell the general direction of the standoff attack. Both our mortar gunners and the ROK artillery had previously scoured the countryside around the base to determine likely launch or firing positions, and they had pre-plotted firing solutions to hit this or that point on the map. When the crater analysis team called in the likely azimuth of attack, our mortars and the ROK artillery began to pound the enemy’s likely firing positions.

As squadron administrative officer, I had not had the normal course of Security Police training including the combat course in Texas, so my post of duty was in the Alternate Central Security Control center. Our intelligence NCO and I monitored the net, the impact points, the crater analysis, and the ROK counterfire, allowing CSC to concentrate on moving sentries, dogs, and Quick Reaction Teams, and calling our mortar pits for high explosive (“HE”) or illumination fires, or in extremis linking the Spooky or Spectre gunships with the flight commander who would call in those fires.

Read Donald Bishop’s full oral history HERE. Learn more about Bishop’s time at Phu Cat Air Base in Vietnam on pages 54–69.