September 11 fundamentally transformed United States foreign policy and shook the country as a whole. This transformation and shock was not limited to U.S. citizens within the mainland United States. Overseas, Foreign Service officers across the globe had their lives and missions considerably changed by such a traumatic event. U.S. Foreign policy itself became focused on combatting terrorism wherever it appeared, but there was also considerable effort at the time to make it clear that this so-called “global war on terror” that began in Afghanistan did not signify U.S. opposition to Islam itself.

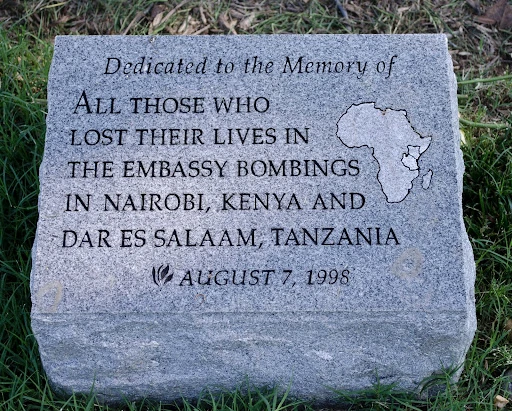

In Tanzania, the fears surrounding the 9/11 attacks were underpinned by the fact that just a few years before, in 1998, Al-Qaeda bombed the U.S. Embassies in both Tanzania and Kenya. These devastating terrorist attacks were on the minds of the Foreign Service Officers in Tanzania on 9/11.

Michael Korff was assigned as a public diplomacy officer to the U.S. Embassy in Tanzania on September 11, 2001. In this “moment in U.S. diplomatic history,” he recounts how he experienced the attacks, and the reactions of Tanzanians and embassy officials from other countries. He also describes how the priorities of his mission and the embassy changed in the aftermath.

Michael Korff’s interview was conducted by Mark Tauber on September 21, 2021

Read Michael Korff’s full oral history HERE

Read the story of the 1998 attack on the U.S. Embassy in Tanzania here and the 1998 attack on the U.S. Embassy in Kenya here. In addition, you can read an interview with James A. Larocco, the Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary for the Near East Bureau during 9/11 here.

Drafted by Gerrit Michmerhuizen

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“One of the towers at the World Trade Center is on fire, there’s been an accident.”

Aftermath of 9/11 in Tanzania:

Q: Right, exactly. Anyway, let’s go ahead and join you in Tanzania. What was the size and shape of the public diplomacy section, now part of state?

KORFF: Well, as you know, up until 1998, USIS [United States Information Service] had an American center downtown in Dar es Salaam. But in 1998, the United States Embassy was blown up by Al-Qaeda operatives. We weren’t in the building at the time, although, as unfortunate as it is, one of the people killed in Dar es Salaam, at the time of the bombing was the spouse of a United States Fulbrighter.

We only had nine people killed in Dar es Salaam, whereas in Kenya, they had 100 or something, it was a much more significant bombing there. Part of the reason is, we occupied the former chancellery of the Israeli embassy. When Israel built something, they built it to withstand these sorts of things. So it was a very strong embassy. And when they left Tanzania when they no longer had their relations, or at least diplomatic relations, the Americans bought the embassy, and so it was a traumatic experience. A lot of our FSNs [Foreign Service Nationals], for example, that I worked with, State FSNs, were traumatized by the experience.

I got there in late August of 2001, and I’m in my second week, and I did not have a television in my office, but the assistant PAO [Public Affairs Officer] had one in his and all of the staff had gone home by then. It must have been 5:30pm or so in the afternoon, our time. The assistant PAO came running into my office and says, “One of the towers at the World Trade Center is on fire, there’s been an accident.” And so I went into his office to watch it on TV. We were watching when the second plane hit the second tower. You know, at first you couldn’t believe that it was happening. It was such an unexpected event.

We had a tie line to Washington, so I immediately called my wife who had stayed behind in Washington for some surgery. She was fine, but our son was on a train from Washington to Manhattan at the time, and everybody’s phone started going off, right? You know, there’s been this bombing in Manhattan, and so everybody wanted to get off the train. Nobody wanted to go into Manhattan, and Amtrak did not let them get off. They had to continue all the way into, I guess, Penn Station.

Ultimately, he, of course, turned around and came back home the next day, but it was quite a trauma. Bonnie drove home and was glued to CNN, thanks to my predecessor I had CNN in the house. I was sort of glued to it, something that most people don’t remember is that, of course, there were a lot of rumors around that day. One of the rumors was that a bomb had gone off in a car next to the State Department, and so that made it sound even worse. So I’m getting more and more panicked. I mean, is there going to be any world left after all this. We didn’t know how extensive it was going to be. Later that night, about 7:30pm, I would guess, or eight o’clock, the chargé called, and she told me that I was to get a hold of all of my FSNs. Oh, you had asked how big the section was, there were two Americans, and I would guess twenty FSNs. She told me I should contact all FSNs, tell them not to come in the next day, and that we would have a meeting of the Emergency Action Committee, or what it was called EAC, to think about next steps. We did have that meeting. But driving in on the twelfth. Our embassy, our chancery was next to the Russian, and driving in that morning, the Russian flag was at half-staff. That was so meaningful to me that finally the world was united, having fought the Soviet Union for so long. Having seen the fall of the Berlin Wall, and everything else, for the Russians to actually be sympathizing with the Americans was a really nice gesture. So the EAC met, we decided that we would have no more than half of our staff come in on alternate days, and so on. That initial period after the bombing was quite dramatic, and we arranged to have a sort of a memorial service at the ambassador’s residence. Mind you, we didn’t have an ambassador, but we held it at the ambassador’s residence. The Marines carried both the United States flag and the Tanzanian flag that became an issue much later, which I can tell you about. Just so you know, normally the Marines refused to hold the embassy the flag of another country.

Q: Okay, okay. You’re certainly right that part of the Bush administration early in this period after 9/11, wanted to make sure that it was understood the administration made a clear difference between relations with Islam and relations with jihad. They also were beginning to ask the public diplomacy to reach out to youth. There had been a feeling that this was an area this was a group that we were not adequately addressing. Was that also going on in Tanzania? Were you asked to, you know, particularly address outreach to youth?

KORRF: Yes, especially Muslim youth. They suddenly found lots of money. All kinds of exchanges became possible, we doubled the normal number of international visitors who went to the U.S. from Tanzania. It was just an amazing period. Lots of opportunities to build up our program and up until then we hadn’t had a translator to translate anything into Swahili. When I asked for money to hire an FSN, to do the translating, no problem. You no matter what I asked for, somehow they found the money. They were happy to give it to us. They were glad that we were willing to do something about it. And it worked out very positively.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in Social Science, Sacramento State College 1966–1970

AM in Education and History, Stanford University 1971–1973

Ph.D in Educational Leadership and History of Education 1970–1975

Joined the Foreign Service 1979

Madras, India—Assistant Branch Cultural Affairs Officer 1981–83

Dar es Salaam—Tanzania Public Affairs Officer 2001–2004