The U.S. State Department is renowned for its diplomacy and foreign policy. However, it is recognized less for its educational programs. FSO Michael Korff worked alongside his fellow United States Information Agency colleagues to help make education and cultural affairs a more prominent aspect of diplomacy.

Korff worked as a middleman between Washington and New Delhi in arranging a performance by the National Theatre of the Deaf. He helped to bring a dance troupe to Mahabalipuram, a popular archeological site in Southern India. He also organized the Arts America programs in Madras and Bangalore.

Korff’s work with the Audio-Visual Program in Madras is especially notable. Although this program organized multiple film festivals at the American Center, Korff noticed that there were few, if any, American officers who attended the festivals. He took the initiative to change the status quo. For example, he made it a point to arrive early at the Center in order to welcome people as they arrived, and he made it a standard practice to give a brief synopsis of the film before the movie began. Similarly, after the screening, Korff would regularly host group seminars, discussing in depth with the audience the various themes of the film. By doing so, Korff succeeded in educating those who attended the festivals, thus achieving a key purpose of this program.

Throughout his career, Michael Korff ensured that his work had purpose, often going above and beyond the usual duty. He spoke with ADST about his career. Read more about Korff’s notable accomplishments in his full oral history HERE.

Dr. Michael Korff’s interview was conducted by Mark Tauber on August 26, 2021.

Read more on Madras HERE.

Read other oral histories on the arts HERE.

Drafted by Jenna Alexander

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“. . . my Muslim chef had prepared pork fried rice for my Muslim minister. Well, that was a scene!”

Disastrous Dining: The Importance of Oversight

KORFF: Something many people don’t know about eastern India is that there are a few very large communist parties. West Bengal had a Marxist government… they had arranged for a minister, a Muslim minister in the Marxist government, to come to my house for dinner, and have a discussion with the speaker. So, we were really excited about it. And as I had done for all of the other events, I simply told the chef to cook.

You know, “On Tuesday, we’re going to have a group of ten people over for dinner. Please make something nice.” And that was the end of it.

I never asked about the menu. I had no idea what to ask for. I just said make something. So, we’re having cocktails before the dinner, and the chief FSN decided to go check to make sure dinner was almost ready: What are we having, everything’s okay, etc. And he goes into the kitchen. Now he was a Hindu Brahmin. But he went in and talked to the chef and discovered that my Muslim chef had prepared pork fried rice for my Muslim minister. Well, that was a scene! So, they quickly delayed the dinner a bit, and they made some white rice. And I don’t know what else we ate, and I have no idea what the topping was. But it just shows you what can happen if you don’t really pay attention to what’s going on and don’t make it your business to oversee everything in detail. In my case… I must not have told him that there was a minister coming and that he was a Muslim. But at the very least, I should have at some point gone over the menu with him to make sure it’s going to be okay.

“. . . they never saw an American officer at any of those showings. I just thought that was wrong. Here’s an opportunity. So, I changed that . . . .”

The Audio-Visual Program in Madras

Q: Now, the audio-visual stuff, was that for presentation in your cultural center? Or where were you planning to have it shown?

KORFF: Most of it… was held at the American Center: we had a large auditorium. And we had film festivals there. All kinds of stuff. When I got there, for example, when we had film festivals… they never saw an American officer at any of those showings. I just thought that was wrong. Here’s an opportunity. So, I changed that… I could welcome people in the lobby and then introduce the film from the stage.

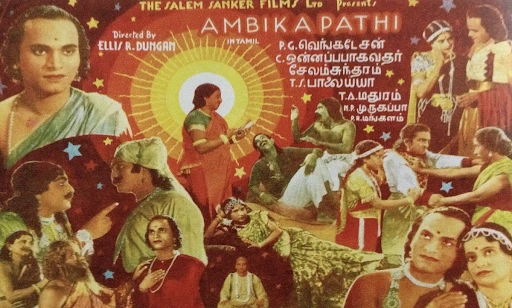

I learned all about a lot of movies that I previously knew nothing about. Because I would then give some background; otherwise, the guests are just coming in for the entertainment. That’s not serving our purpose. I didn’t think so: I wanted to get a little more out of it. If I were to do it today, I would then have discussion groups afterwards. I would ask… how does this compare with a Bollywood movie…? You may or may not know this, but there are more South Indian films made each year than there are Bollywood (Hindi) films made each year. Everybody knows about Bombay and Bollywood, but they don’t know much about Tamil cinema.

Q: Interesting. I am curious… are there major differences between Bollywood movies and Tamil?

KORFF: I don’t see the difference. Other than language, it’s the same. They are difficult to sit through because they last so long, right. And there’s so much dancing and singing. A film may be filmed in Bombay one year in Hindi and in Madras the next year in Tamil.

In addition to those videotapes and movies that we presented in the auditorium, I would say one week per month I had to be outside of Madras, either other places within Tamil Nadu or places in Kerala. We took big videotape players and big monitors in the back of our trucks, and we would drive all over South India, set those up, and play them. Now, of course the stuff that we got that was policy-oriented was always going to be in English. So, you had to choose your audience based on whether or not they’re going to know what’s going on so that you can then answer questions after the program or whatever.

But we also would have one night, usually with the Vice Chancellor—often an alumnus of an American or Soviet university—of the local university, where we would play recordings of Western symphonic music, and this was a big hit. They craved Western classical music in a way that was really surprising. And so, we would have an evening that was not very policy-oriented, but it was a big hit among our audiences, it was a way of letting them know, we care about you. We also want to talk to you about our policy interests. But we also want to do this for you.

“. . . we invited people to my residence, provided snacks and an ample supply of liquor, and dutifully sat through the film. We were then able to report… that influential Indians had seen [the] film.”

An Appreciation of the Arts: Film, Dance, and Art Programs in Madras

Q: Were there other consequential events you remember from Madras that had a beneficial effect in the rest of your career? Other skills or talents that you learned?

KORFF:…There are a couple of other interesting events from my assignment to Madras that point to the foibles of having high-ranking Washington officials decide on programming at posts abroad.

First, you’ll recall that I was responsible for audio-visual programming in Madras. In 1982, the Director of USIA, Charles Z. Wick decided that we should broadcast a film entitled Let Poland Be Poland narrated by Charlton Heston at every USIS post abroad. The Government of India (GOI) was vigorously non-aligned, which meant that any propaganda effort that might offend the Soviet Union was to be avoided. The GOI prohibited USIS India from presenting the film at any of the four American Centers. We were, however, able to skirt the prohibition by presenting the film at diplomats’ homes. I was the designated diplomat for Madras. So, we invited people to my residence, provided snacks and an ample supply of liquor, and dutifully sat through the film. We were then able to report to Delhi, and Delhi could report to Washington that influential Indians had seen Charlie Wick’s film.

The other Washington-directed event was a “gift” to the post. Washington offered New Delhi, and New Delhi offered to the posts, the opportunity to present a performance of the National Theatre of the Deaf. My staff, which knew little about programming the deaf, found a venue for the performance and invited every deaf person or organization focused on people with disabilities to the performance. My admiration for the local staff is profound: We presented a successful performance and found an audience. At a time when we were focused on the DRS audiences, we reached out to a general audience. It was quite a feat.

Another bright idea from Washington was that we program a dance troupe that wanted to perform a free concert at Mahabalipuram, one of the great archeological sites in South India, located right on the Indian Ocean. It’s about 90 minutes south of Madras. The Deputy Director of USIA floated the idea that we arrange a free evening performance… We explained that there was no electricity, no lights, no seating, no way to control access, etc. We tried to get across that finding an audience in a land of a billion people was not a problem. Ultimately, we prevailed and we were not saddled with supporting a visit.

One set of programs may be of interest to you: We had several Arts America programs that we offered in Madras and Bangalore. These included dance troupes, jazz musicians, and drama groups… By co-sponsoring, we were able to use any revenue that might be raised at the presentations to help fund the cost of renting venues, print tickets, etc. The cosponsor benefited by being associated with us—and it kept a modest honorarium.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in Social Science, Sacramento State College 1966–1970

AM in Education and History, Stanford University 1971–1973

Ph.D in Educational Leadership and History of Education 1970–1975

Joined the Foreign Service 1979

New Delhi, India—Junior Officer Trainee 1980

Calcutta, India—Junior Officer Trainee 1980–81