When Ulric Haynes joined the U.S. Foreign Service in 1964 as the desk officer for Southwest Africa, the United States had begun paying more attention to the region. It had become a strategic interest—important to security, countering the Soviet Union, and for its abundant natural resources. The repressive apartheid policy in South Africa and its increasing international isolation, however, made regional relations more complicated for the United States. The U.S. government hoped that Western pressure could produce some political realignment. To make matters even more complicated, South Africa had control over a number of territories in this part of Africa. The United Nations and the International Court of Justice were working tirelessly to find a political solution and prevent serious confrontation.

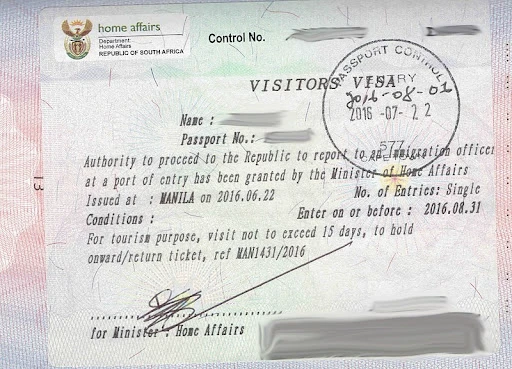

As the first desk officer for Southwest Africa, Mr. Haynes was scheduled to make visits to the consulates in Namibia and the British High Commission territories (now Lesotho, Swaziland, and Botswana). He would have to travel through South Africa in order to get to the destinations on the visit schedule. However, after the South African government learned that Mr. Haynes was African-American, they refused to issue him a visa to travel to South Africa. News of this problem made its way back to the freshly sworn-in U.S. president, Lyndon B. Johnson. The president was able to convince the South African government to change course, making Ulric Haynes the first black American diplomat to get a visa to South Africa.

Gerhard Mennen “Soapy” Williams, who served at the time as assistant secretary of state for African Affairs, provides further insight into U.S. relations with African countries, describing how the United States sought to strengthen diplomatic ties with South Africa and fight back against the notion of strong white supremacy. Williams knew Haynes to be a very competent man and saw the importance of Haynes’s visit to these diplomatic posts. Furthermore, Williams was with former Secretary of State Dean Rusk when he made the call to the South African ambassador stating, “This is a matter of high importance to the State Department whether

you’re meaning to tell us that this person isn’t competent on the one hand or that because he’s

black and you’re not going to let him in.” When the South African ambassador pushed back with conditions for Mr. Haynes’ arrival Dean Rusk said, “This is absolutely unacceptable to us! This is insulting to the Department in the way you’re treating one of our officers.”

After leaving the Foreign Service and returning, Ulric Haynes Jr. became the United States Ambassador to Algeria in 1977. Despite his position and affiliation with the United States government, he encountered blatant racism during his career on a number of occasions. No matter the challenge, he always confronted the situation straight-on and with professionalism. If it were not for the change in presidency, Mr. Haynes would likely have been recommended to serve as the next ambassador to Poland. Decades later, the State Department still struggles with meeting its goals for diversity, especially in ambassadorial positions. However, it has made strides to diversify the Foreign Service to make it more effective and truly representative of the U.S. population as a whole.

Ulric Haynes Jr.’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on April 20, 2011.

“Soapy” Williams’ interview was conducted by William Moss on January 28, 1970, and is housed at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

Read Ulric Haynes Jr.’s full oral history HERE.

Read “Soapy” Williams’ second oral history HERE.

To read more about distinguished and important moments in the careers of African American Diplomats, click HERE

Drafted by: Kaitlyn Flynn

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

Ulric Haynes Jr.

Washington, DC—Desk Officer for Southwest Africa, 1964

Algeria—Ambassador, 1977–1981

“I decided we could not afford to have an American family with this kind of prejudice representing us abroad . . . .”

Q: Well, I mean you were an African hand by this time. How did you feel about our role in the Congo as you got inside the administration?

HAYNES: I was quite familiar from the advent of independence in the Congo with the events that were going on. Subsequently, when Soapy Williams was the first Assistant Secretary for African Affairs in the State Department I traveled with him to the Congo several times

and sat in on his discussions with Moise Tshombe and others. So I was immersed in Congo affairs.

Q: Well, how did you feel—from the perspective of the National Security Council, what was happening in the Congo? I mean we were—

HAYNES: I felt, and still feel, that the situation was politically chaotic and totally unpredictable. There were elements involved that we did not understand, such as tribalism, personal vendettas, and a very high level of incompetence when it came to governing the country.

Q: But the country was just too big and important to write off, wasn’t it?

HAYNES: Exactly. It was such an important source of precious medals, and also all of the other emerging nations of Africa were watching what was going on in the Congo, and either learning good lessons from them, or learning lessons from them that were not in our national interest. The major lesson being how to play off the Soviet Union against the United States. All it took was an announced flirtation with the Soviet Union to excite the interest and involvement of the United States.

Q: Well, did you feel that there was much to be gained in most—I mean was it UN votes or keeping the math and turning red in Africa or were you sort of picking on key areas that we had to hold on?

HAYNES: It was all of those things. And you mustn’t forget that at that time one of our major headaches was the apartheid government of the Republic of South Africa. At that time apartheid was in its heyday. And there were all sorts of—yes, it was all of the things you mentioned. There were votes at the UN, there were economic and commercial interests in the enormous natural resources of Africa. At the time we were only beginning to get a sense of the enormous resources of oil in certain parts of Africa. So we had commercial and political interests in what was going on in Africa at the time.

Q: Well, what was the atmosphere within the National Security Council regarding South Africa, which was, as you say, at—apartheid was in its heyday.

HAYNES: Well, I’ll give you two anecdotes that will help you to understand the, the climate on the inside of the national government. Dean Rusk was Secretary of State at the time and his daughter, while he was secretary of state, married an African American. The South African—some South African politicians that apparently made some nasty comments about that in the press and Dean Rusk was of course enraged and it immediately cooled his professional and personal relations with the South African ambassador to the United States. And, at the time I was the first desk officer for Southwest Africa which is now Namibia, and the British High Commission territories, now Lesotho, Swaziland, and Botswana. I was scheduled to make a routine visit to the territories under my supervision at the department. And the South African government, learning that I was an African American, refused to grant me a visa to transit South Africa to get to these territories for which I was responsible. And they absolutely refused to allow me to visit Southwest Africa, which was under their jurisdiction as a result of a League of Nations mandate. When Lyndon Johnson heard that I’d been denied a visa, he made it clear to the South African ambassador to the United States that unless I did get a visa to visit my territories, he would arbitrarily declare several of their embassy personnel persona non grata in the United States. And of course they caved, but they caved only in part and gave me a visa to visit the High Commission territories, but did not allow me to visit Southwest Africa. However, they were not allowing any American diplomats to visit Southwest Africa at that time.

________________________________________________

Q: How did you find the people dealing with Algeria in the State Department treated you? Because you weren’t the normal political appointee. I mean you’d certainly been around the block.

HAYNES: I called myself an “inside outsider.” I already knew so many of them. Harold Saunders, who was then the assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern Affairs had been a graduate student when I was a law student at Yale.

And we served together on the National Security Council staff. So, I knew a lot of the people that I was dealing with. And that was a help.

However, I will never forget, after having arrived in Algeria at the end of June, my first really official function before I presented my letters of credentials, was hosting the American embassy Fourth of July celebration. And as I passed—on the grounds of my own embassy residence—as I passed a group of American embassy wives I heard this snip of a conversation. One wife said to the other wife, “Have you seen what Washington sent us this time?” And the other wife replied, “Yes. And I’m not going to have it in my house.” They were talking about me and my appointment.

Q; Oh, my God.

HAYNES: And the fact that I was a black ambassador, which was still pretty rare. You know, I was—while Algeria’s considered the Near East in the State Department, it was not a typical appointment for a black ambassador.

Q: No, no, I—yes, the—well—

HAYNES: Let me tell you how I dealt with that one.

Q: Yes.

HAYNES: One of my first official acts was to schedule a tour all of the American embassy residences rented or owned in Algiers to give the lie to the Embassy wife who said that I would never set foot in her house. Sure enough, when I got to her house, she did not offer me so much as a glass of water.

Q: Oh, my God.

HAYNES: And I’m going to tell you, it’s—from my point of view, that wrecked her husband’s career. Because as soon as I could, I decided we could not afford to have an American family with this kind of prejudice representing us abroad, and I arranged for his transfer. It’s something that we just cannot tolerate.

Q: Absolutely not. I mean, you know, badmouthing and, I mean you’re just not getting the full cooperation.

HAYNES: Well, not only—not only that, but if she had that attitude toward her ambassador, what did she think of the Algerians?

Q: Oh, my God, yes.

HAYNES: And I must say, I wasn’t far from wrong. Not long afterwards, we constructed a swimming pool for the embassy staff and one of the administrative officers came to me and said he was speaking on behalf of the American families who did not want to have Algerians swimming in the same swimming pool with them. I was dumbfounded. When I recovered I said, “Listen. Do you know to whom you’re addressing this request? You’re addressing this to someone who as a little boy couldn’t swim in public swimming pools because of the color of his skin. And you want me to turn around and treat other people the same way? Get out of here!” I was furious!

Q: (sighs) How were you received when you arrived there?

HAYNES: (laughs) With surprise. I’ll give you a funny anecdote. When I presented my letters of credentials to President Boumediène in the presidential palace I was accompanied by my DCM who was white. And as I approached the president to present my letters of credentials, he extended his hand to my deputy, rather than to me. And I said, “Excuse me, Mr. President, but I’m the ambassador.” I cannot tell you how embarrassed he was. And I later used that to my advantage. Thereafter, whenever I requested an appointment with the president, I got it. He was so embarrassed. But, hey, we have ourselves to blame too.

Gerhard Mennen “Soapy” Williams

Michigan—Governor, 1949–1961

Washington, DC—Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs African affairs, 1961–1966

Manila, Philippines—Ambassador, 1968–1969

“This is insulting to the department in the way you’re treating one of our officers.”

I think I might tell you one story for the record which relates more to Secretary Rusk than it does to Kennedy, but since Rusk’s position and his character relate directly to the Kennedy choice, I think it’s important. One of the things that we kept trying to do in our African policy development was to strengthen our embassies and our representation in those countries which were directly in contact with the bastion of southern white supremacy or in the tiers further back, so that we could help those countries be stronger in their political and economic independence, so that they would be in a position to deal with this white supremacy force. And one of the things that we did was to set up a vice consulate system in the so-called British crown colonies, as they then were, or protectorates: Basutoland, Bechaunaland and Swaziland.

When we started out, we had one young officer and actually his wife for his secretary to cover all three of them. But then we wanted to symbolize and emphasize this by a similar setup in our organization in the bureau in Washington, and we put in a very competent young Negro, Ulrich Haynes. And he is the man I spoke of previously about being stolen from me to go into the White House. Well, if he was to be competent in the area, he had to go visit it. And the only way you can get into these enclaves is to either fly over South Africa or to go through South Africa. Well, when I visited these areas, I had a military plane and I could over fly South Africa, and so I was able to get around the problem that they didn’t want to give me a visa. But we either couldn’t or didn’t want to do that with Haynes because normally you wouldn’t send a man of that rank in a military plane.

So we applied for a visa, and the South Africans didn’t come up with a visa. And finally the secretary called the South African ambassador whether it was true that Rick Haynes was being denied a visa to pass through South Africa to go to these enclaves because he was black because he said, “There isn’t any other reason that we can discover.” And he said, “This is a matter of high importance to the State Department whether you’re meaning to tell us that this person isn’t competent on the one hand or that because he’s black and you’re not going to let him in.” And the South African ambassador was very embarrassed, and so he said he would check with his country. So when he came back again he said, “Well, we will offer him a visa, but under certain conditions that he can come in but he’ll have to fly out in a military plane,” or something of that kind, I forget exactly. Well, Dean Rusk made short work of this. He said, “This is absolutely unacceptable to us! This is insulting to the department in the way you’re treating one of our officers.” And he said, “We want this fellow to go in, and we’re very much displeased.” Well, he called me back or held me back when the ambassador left and had the ambassador wait outside. And he said, “Did I really give it to him tough enough?” He said because if he didn’t, “I want you to take him downstairs and finish the job.” And I think this is, you know, a picture of Rusk which, of course, antedates his daughter’s interracial marriage, that puts this Georgia gentleman in a slightly different light from what some people would see him. Now Rusk may have considered this, you know, an insult to a Foreign Service officer rather than an interracial thing, but in any event, he was just as tough with this South African ambassador as I imagine he’s ever been with any kind of ambassador. And this position was made clear beyond peradventure. And I was quite proud of him and quite pleased. Well, to end this story, Rick Haynes went to these countries through Johannesburg, and he laughingly said he had the best treatment in customs that any citizens visiting South Africa ever had.