On June 26, 1963, President John F. Kennedy stood in front of some half a million people in West Berlin and delivered a powerful speech in support of democracy and freedom, which became famous for its strong stance against the Soviet Union and Kennedy’s use of German. The phrase “Ich bin ein Berliner” became the pinnacle of his speech, producing long applause and cheers from the crowd. It was clear to his advisors and the Germans in the crowd that Kennedy did not have an ear for languages or pronunciation, but his idea to add in German phrases to the speech served well to connect him to the people of Berlin, helped boost their morale, and showed his unwavering support for their plight.

While the phrase has its place in history, it has also led to a long-lasting urban legend that Kennedy misspoke by including the word “ein.” In northern Germany, a Berliner was a jelly doughnut. Therefore, President Kennedy supposedly said “I am a jelly doughnut” and the crowds were amused by his mistake. However, linguists have pointed out that not only is “Ich bin ein Berliner” acceptable, it can be argued that since Kennedy was not actually a resident of Berlin, it was more correct. The laughter came after Kennedy deadpanned, “Thank you for correcting my pronunciation” after the interpreter repeated the phrase in German.

Robert Lochner served as the Director of RIAS, the Radio in the American Sector in Berlin, from 1961-1968. He accompanied President Kennedy as one of his translators and had a front row seat for the speech. He recalls his own experiences with the President and gives a firsthand perspective to the atmosphere of those three days in Berlin, culminating in Kennedy’s words on the steps of the Rathaus Schöneberg, the Berlin City Hall. He was interviewed by G. Lewis Schmidt beginning in October 1991.

Lucian Heichler served as a Political Officer in Berlin from 1959-1965. He also accompanied President Kennedy, serving at his side for the eight hours he was in Berlin. He discusses his contribution to the visit and also gives an account of how President Kennedy was received and perceived by the German people during that time. He was interviewed by Susan Klingaman beginning February 2000.

You can listen to the audio of the speech or read about the construction of the Berlin Wall and the reaction to JFK’s assassination.

“Mr. President, I think that went a little too far”

Robert Lochner

Director of RIAS (Radio in the American Sector/Rundfunk im Amerikanischen Sektor) in Berlin, 1961-1968

LOCHNER: General Clay, whose interpreter I had been for the whole period he was Head of Military Government, recommended me to President Kennedy, so a few weeks before his visit I was called to Washington and [National Security Advisor] McGeorge Bundy asked me to prepare a few simple phrases in German and to try to rehearse those with the President. So on a typewriter with large letters I prepared a few very simple sentences. McGeorge Bundy took me into the Oval Office, there was nobody else there, and presented me.

I gave one copy to the President and slowly read out the first sentence in German and asked him to repeat it. When he did and looked up he must have seen my rather dismayed face because he said, “Not very good, was it?”

So what do you say to a President under those circumstances? All I could think of was to blurt out, “Well, it certainly was better than your brother Bobby.” He had been to Berlin and tried some sentences in German and had butchered them in such a fashion that one couldn’t possibly guess what he was trying to say.

So fortunately the President took it lightly, he laughed and turned to McGeorge Bundy and said, “Let’s leave the foreign languages to the distaff side.” Of course, everybody knows that Mrs. Kennedy spoke fluent French. So he had not intended to make a single statement in German and that is why it is relevant to what happened later to give this background.

I interpreted for him the whole three days that he was in Germany starting at the airport in Bonn. The receptions in Bonn/ Cologne, and Frankfurt were as enthusiastic as you could wish, but the one in Berlin overshadowed everything that we had experienced in Western Germany.

We started out in a big open car. Kennedy and [Chancellor Konrad] Adenauer sitting in the back, [then Mayor of Berlin, later Foreign Minister and Chancellor] Willy Brandt and myself sitting on jump seats.

There was a glass partition between us and the front. We had hardly driven 20-30 yards when President Kennedy, noticing there was a bar on our side of the glass where one could hold oneself, suggested that they stand up to be better seen. So Willy Brandt and I pushed back our jump seats and I crawled through the legs of Adenauer and President Kennedy and sat in lonely splendor on the rear seat. Of course I wasn’t needed at all and felt very unhappy.

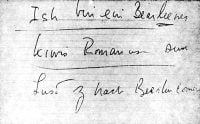

For all the years since then at the USIS [U.S. Information Service] office in Berlin there has been a picture showing the three gentlemen standing and me with a very unhappy face in the rear because I felt totally useless — as we were driving I couldn’t get out. When we stopped for his major speech and walked up the stairs to the City Hall, he called me over and said, “I want you to write out for me on a slip of paper ‘I am a Berliner’ in German.”

We first went to Willy Brandt’s office while hundreds of thousands cheered outside. I quickly, by pencil, wrote it out in capital letters and he rehearsed it a few times. And that is really the whole story. I am assuming it was in English in the original text. There have been all sorts of stories about the manuscript, etc. I can only tell my part.

After the speech we came back for a little while to Willy Brandt’s office where there was a short reception with some of the top politicians and, of course, I had instructions to stay close to the President in case he talked to some Germans.

So I couldn’t help overhearing McGeorge Bundy saying to him, “Mr. President, I think that went a little too far.” So, McGeorge Bundy, like myself and many others, instantly realized that his making this statement in German gave it that much more weight than if he had said it in English.

I find this theory confirmed by the fact that the President seemed to agree and thereupon and then and there made a few changes in his second major speech later on at the university, changes that amounted to making a few more conciliatory statements, if you wish, towards the East. I only describe my own personal experience. I conclude from that that he agreed.

It didn’t have any effect on the famous statement, of course, but it is interesting to me that McGeorge Bundy like myself had this instant reaction that the statement was that much stronger for having been made in German and millions of German since then have repeated his “Ich bin ein Berliner” while they probably would not have quoted “I am a Berliner.”

Q: President Kennedy may have anticipated that and did it purposely.

LOCHNER: Yes, and that is probably why he did it. My own personal conclusion is that this overwhelming reception by the Berliners, which was so incredible, even after the enthusiastic receptions in Bonn and Frankfurt, made him feel he wanted to do something even stronger. That is my assumption. Why else would he have done it?

“Thank you for correcting my pronunciation”

Lucian Heichler

Political Officer in Berlin, 1959-1965

HEICHLER: I worked on the Kennedy visit. I was a member of the control officer team. I was with Kennedy the whole eight hours he spent in Berlin. I drafted one of his speeches. It was actually not used the way I drafted it. I wrote the draft of the City Hall speech, but he used most it at the Free University, and so the famous line, “I am a Berliner,” was not mine, I’m sorry to say.

The [Germans] were all in love with Kennedy. Totally and completely, and if Jackie had come along, it would have been an even greater love feast. She didn’t, which was a pity, because I would have liked to meet her at least once. I was tremendously taken by John Kennedy myself. He actually shook my hand, but that was because he took me for a German.

Q: What did he say besides “I am a Berliner” that struck a chord?

HEICHLER: His youthful enthusiasm; it was the strength with which he spoke — I mean it was the whole powerful passage that led up to this “I am a Berliner.” “If you want someone to see so-and-so, then let him come to Berlin,” over and over. It was a fantastically good speech.

There was this one little interplay I was privy to because I was standing two feet away from him during the minutes-long applause which erupted after the “I am a Berliner” line. The interpreter, taken by surprise, simply repeated the phrase in German.

This interpreter was a Herr Weber, assigned by Adenauer as the best German-English interpreter in the Foreign office, but when Kennedy said, “Ich bin ein Berliner,” Herr Weber automatically repeated, “Ich bin ein Berliner.”

And Kennedy, who had this wry sense of humor, quickly leaned over to him and said, “Thank you for correcting my pronunciation.” A few of us overheard this and never forgot it.