Richard M. Nixon’s presidency was a tempestuous mix of stunning foreign policy achievements (his trip to China) and shameful lapses in morality and judgment (the Watergate scandal). After the host of criminal activities (bugging the offices of political opponents, harassing activist groups, and breaking into the Democratic Party headquarters) came to light, Nixon faced impeachment. On August 9, 1974, Nixon became the first and only President to resign. Later, President Gerald R. Ford granted Nixon a “full, free, and absolute pardon,” though Nixon always maintained his innocence.

Stephen M. Chaplin shares his experience from Romania, where people saw Nixon’s resignation as a weakening of the American system that could give the USSR the upper hand. He was interviewed in 2001. James E. Goodby (interviewed 1990) describes seeing Nixon just prior to his resignation at the U.S. Mission in NATO in July ’74 and later being given a pep talk by a distressed Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who recounted the good Nixon had done in foreign policy.

Dr. William Lloyd Stearman (1992) worked in the White House as part of the National Security Council staff and notes how Chief of Staff Alexander Haig was the de facto President at this time and describes the emotional Nixon as he famously departed the White House in a helicopter and Gerald Ford’s swearing-in. They were all interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy.

Read about Nixon’s historic trip to China and a different perspective on Watergate.

“No one is above the law”

Stephen M. Chaplin, Cultural Affairs Officer, Bucharest, Romania, 1974-1977

CHAPLIN: I arrived there in early August of ’74. This was when Watergate was going on. I got there about two days before President Nixon resigned. The library was closed at the time for August because Romanians, like a lot of Europeans, take the month of August for vacation.

We reopened the first Monday in September or the day after because of Labor Day. The head librarian came to me running one day, and she said, “I have a question for you.”

I said, “Yes, Zonda, what is your question?” She said, “One of our colleagues here wants to know where the condolence book is.”

I said, “What?”

She said, “Yes when a president has resigned, we want a condolence book to sign showing the American people our solidarity and condolences.”

I said, “Well there isn’t going to be a condolence book. This is the American political process in action.”

But the identification with Nixon had developed. He was the first president to visit. They looked on this as kind of a national tragedy for Americans, whereas we would say the process is washing our dirty linen in public, so be it. No one is above the law. They didn’t quite understand that, and they feared, I think, that our system might be weakened which meant that the Russians somehow might take advantage of it from the Romanian perspective. So we had to explain that.

Before I left in ’77, I showed the picture All the President’s Men. As I did with all of our films, I sent out a notice in Romanian giving a little synopsis of the film because none of these were subtitled. They were all in English. None of these films appeared commercially in Romanian theaters. Then I did an introduction in Romanian to the audience.

I explained this was a film based on the writings of two journalists….The writing of the stories by The Washington Post journalists, Woodward and Bernstein, but that again it was a view from two people.

I showed the film, and talked to a few people afterwards. Some, even some people who admired the United States — we are talking about some fairly intelligent people, not just necessarily the man off the street you ask a question — couldn’t relate to the fact that this was a commercial film.

They were seeing things through their Romanian upbringing…. a leader deposed in their terms, as being government propaganda to discredit the former president put out by the new leadership. I raised the question.

I said, “Well, if this were the case, why was the man he chose to be his Vice President, Gerald Ford, why did he replace him?”

The answer was well, it was the Democrats and the media who were out to get Nixon and this is a temporary thing and so forth. Well, indeed Jimmy Carter defeated President Ford. That probably reinforced their views….

“It was just like a face carved out of wood — no expression”

James E. Goodby, Political-Military Bureau, 1974-1977

GOODBY: I was Chargé at the US Mission in NATO in July of 1974, because the foreign ministers were meeting at that point in Ottawa, there to sign the Atlantic Charter and have one of their summer meetings. And it was at that point that Nixon came through on his last European swing before resigning. He resigned August 9, 1974, and this was July, I believe.

I went out to receive him at the airport and talk to his advance party and so forth and so on. And I was really shocked by his mien. Actually it was the first I’d seen Nixon close-up in quite a while. He had been at NATO headquarters and I’d seen him before, but this time he came through the receiving line and I shook hands with him.

And his face was like a wooden mask. I mean, it was heavily painted, in effect, a kind of orange color, which I guess he liked because it made him look tanned. But it was just like a face carved out of wood — no expression.

And I thought, “My goodness, what this man is going through.” It was obvious that he just was not himself and not sort of the former Nixon who was, as I had remembered seeing him, a much more animated kind of person. But this was a guy that obviously had in mind, you know, “Who is this guy? Is he for me or against me?” And that was kind of the sensation I had as he went through that receiving line.

Anyway, it was a short visit. He gave a talk and went on Moscow and then he went on to resignation. So that was the last time I saw him, and it was quite a shocking experience to see a President of the United States looking like that.

Well, in the summer that I went back, and I arrived back in Washington just a few days before Nixon resigned, I became the Deputy Assistant Secretary, or Deputy Director as it was called then, of the Bureau of Political-Military Affairs….

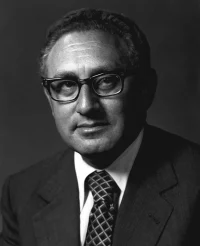

The day before Nixon announced his resignation, all of us at the rank of Deputy Assistant Secretary and above were called up to the eighth floor of the State Department [the Protocol rooms] by Secretary Kissinger and we were informed that Nixon was going to resign.

Kissinger made a little speech in which he said that the accomplishments of President Nixon in the field of foreign affairs had been very considerable (those were almost his exact words). He then commented about President Ford, who would be taking over, and that he expected to be working closely with him.

It was kind of a pep talk, you know, not to be too upset by this, but also not to be in a mood of gloating or good cheer about this, obviously, that Mr. Kissinger was quite seriously affected by this. Of course, he himself had been going through a bit of personal anguish at this point, as we all know.

It was a very somber meeting, I must say, to be told that a President of the United States is going to resign the next day — the first time in history — and to hear from this man who was now close to the pinnacle of the American government telling us how we should think about it and connect ourselves.

“Al Haig was the de facto President, running the day-to-day operations”

Dr. William Lloyd Stearman, White House, NSC Staff 1971-1976

Q: Did Watergate play at all on what you were doing?

STEARMAN: Oh, heavens, yes. I am glad you mentioned that….It had an enormous effect on Kissinger’s Vietnam decisions because he felt the Presidency had been so weakened by Watergate that the American public, and certainly the Congress, would not continue our support for the Vietnamese forces much longer.

And that is why he was so anxious to cut the kind of deal he did in October 1972, which I felt at the time and feel now was very unfortunate and a big mistake; nevertheless, he felt that because of Watergate — and he told me this personally — he just didn’t have any other choice.

Now bear in mind that Watergate hadn’t really come to the fore in late 1972. The whole concern was then overblown, because Nixon was a shoo-in against [Democratic candidate George] McGovern. Nobody was really that worried about Nixon’s losing the election. You had these juvenile lower-level characters, acting without high-level instructions, who thought they could discover some Democratic secrets by breaking into the Democratic Headquarters at the Watergate.

The whole Watergate scandal did eventually have great impact on our policy. The more that came out, the weaker the Presidency became. We all felt that. This was particularly true in 1973.

Another thing one should bear in mind is that for the last sixteen months of Nixon’s incumbency, actually [White House Chief of Staff, later Secretary of State] Al Haig was the President of the United States. He was a de facto President running the day-to-day operations, while Nixon would make some of the major decisions; however, Nixon was so totally wrapped up in Watergate that he was a part-time President at best. Haig never told me this, but everybody more or less assumed this was the case. I knew Haig quite well and could see that he was making the day-to-day decisions.

The absolute nadir came when Nixon resigned. We knew about a week ahead of time that he was going to leave office. I then expected the White House to substantially lose authority. This was in 1974.

I was still trying my best to get equipment sent to Cambodia and to the Vietnamese and was meeting increasing resistance from the Pentagon and others, who were no longer interested in what went on in Southeast Asia, despite everything that was happening there. I expected that with Nixon’s downfall I would get zero cooperation from my colleagues in the bureaucracy, but quite the opposite happened. I had never found them to be more cooperative.

I think those people were shaken by the fact that we had a vacuum at the top and felt that those of us who were trying to hold things together at the top deserved support. Now this is just one man’s view, but at least, my own subjective impression at that time was that people were all behind us to a remarkable degree, far more than had been the case before.

“Then we walked out to the South Lawn, and waved goodbye as Nixon got into his helicopter and flew off “

Then we had to experience the sad episode of Nixon’s embarrassing, maudlin speech that he gave just before he departed — we were all forgathered in the East Wing of the White House for this farewell. The poor man sort of rambled on and on. I had never seen him wear glasses before, but he would put them on and take them off. He had notes on some sheets of yellow pad paper in his inside coat pocket, which kept shifting into view across his tie.

The whole thing was terminally pathetic. Everybody was there. I looked toward Kissinger, and saw he was seated with the Cabinet. There were also Members of Congress and others present. We from the White House staff were sort of scattered around. Just about everybody was crying.

I was happy to see him go, in a way, but the thing was so pathetic that you felt sorry for all involved, particularly for his poor family bravely standing up there. Then, we walked out to the South Lawn, and waved goodbye as Nixon got into his helicopter and flew off “into the sunset.”

We walked back through the West Wing, where there were still pictures of Nixon and his family on the walls and then back to the EOB [Executive Office Building].

Later, my assistant, an FSO [Foreign Service Officer] who was a rather forward Irishman by the name of Kenneth Quinn said, “Why don’t we see if we can go down and see Jerry Ford’s swearing in?”

I replied, “We are not invited to that. That is only for the top leadership, the Supreme Court, the Cabinet, Members of Congress. Only the select, the most senior people in The White House can go to that.”

“Well,” he said, “Let’s try anyway.”

We got in the elevator on the third floor of the EOB and it stopped on the second floor. When the doors opened, there was Jerry Ford and two Secret Service men.

We said, “Oh, Mr. Vice President, we will get out for you,” whereupon Ford said, “That’s okay there is room for all of us.”

So we all went down and marched to the West Wing together. Everyone assumed that Ken and I were part of his entourage so in we went, unhindered.

So I was back again in the same room I had been a couple of hours before watching Nixon’s pathetic farewell. Now it was a different world. Everybody was upbeat and smiling. I saw the same Cabinet members all sitting in the same places they had been, but now all were wreathed in smiles.

Jerry Ford was sworn in and we walked back through the West Wing. Now there were already pictures of Jerry and Betty Ford all over the place. It was fast work on the part of those responsible for such things. It was “The King is dead, long live the King!”