The Madrid Peace Conference, held from October 30 to November 1, 1991, marked the first time that Israeli leaders negotiated face to face with delegations from Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, and, most importantly, with the Palestinians. In order for this moment to happen, both the United States and the (now former) Soviet Union had agreed to host the conference. Over a tense three days, several bilateral and multilateral talks were scheduled with the goal of covering a wide variety of issues, from the economy to the environment.

As a result, further negotiations were held at the Department of State in Washington, which eventually led to the signing of the 1994 peace treaty with Jordan. It was also the catalyst for the set-up of private talks in Norway, which became the Oslo peace process. For Israel, the talks led to the decline of the Arab boycott and an increase of states that recognized it as a country and the near doubling of its diplomatic relations. Unfortunately, the loftier goals of greater cooperation and eventual peace and stability in the region never materialized.

Kenton Keith, at that time the Public Affairs Officer in Cairo, was called upon by Secretary of State James Baker to assist with the conference. Also assisting with the conference was the U.S. Ambassador to Israel at the time, William Andreas Brown. Kenton Keith was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy starting in June 1998. William Andreas Brown was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy starting on November 3, 1998.

Read about Secretary Baker’s behind-the-scenes negotiations before the Madrid Conference and about the first Intifada in 1987.

“I can tell you there wasn’t a dry eye in the place”

Kenton Keith, Public Affairs Officer, U.S. Embassy Cairo, 1988-1992

KEITH: [The Madrid Conference took place] in the fall of 1991. The process began just after the Gulf War in 1991 and culminated with a series of very intense and successful meetings Secretary Baker held with had with leaders, resulting in the rather sudden decision to meet in Madrid….

The Madrid Peace Conference was co-sponsored by the Russians and the Spanish with the United States, of course. Everybody knew that there was going to be stupendous media coverage there, and with a major media challenge for the organizers. All sides would obviously want to get their stories out to the public, and the organizers wanted to be sure that media coverage didn’t actually drown the negotiations. And the basic setup was tricky.

The Palestinians were supposed to be part of the Jordanian delegation when, in fact, that was true in name only. The Jordanians had their own media interests and pursued them. That was equally true of the Palestinians.

Hanan Ashrawi (pictured; photo: Miriam Alster/FLASH90) was the major spokesperson for the Palestinians and nobody even bothered to maintain the fiction that she was under some kind of control or supervision by the head of the Jordanian delegation. This was technically a violation of the agreement with the Israelis, but in the development of the conference it simply couldn’t be helped.

As anybody might have predicted, the world media wanted to hear from the two main protagonists, the Palestinians, whose voice was Ashrawi, and the Israelis, represented by Bibi Netanyahu, and the U.S. The Russians made almost no public statements, nor did the Spanish, whose main contribution was excellent logistical support.

Naturally, there were confrontations at Madrid. In the big press palace there was jousting between the Israelis and the Arabs, more diplomatic than usual, but still quite pointed. They had to put their press offices in the same part of the building, so there were Arabs and Israelis whose offices were just next door, and this provided opportunities for unusually close contact. The proximity of the rival delegations was especially interesting to the American press who picked up some of these encounters in the hallways.

One such report landed in the Style Section of The Washington Post, for example, describing a rather provocative, highly stage-managed incident in which an Israeli delegation member challenged a Palestinian to be photographed shaking his hand. The much more worldly Palestinian, a university professor as it turned out, calmly took the Israeli’s hand, turned and smiled for the camera.

Madrid was an amazing experience for all of us who took part in it and especially for all of us who had been working on Middle East affairs and the peace process for a long time.

There was the memorable moment when the Israelis and the Syrians sat down together at a schoolhouse in Madrid some distance from conference headquarters. In the press center we were crowded around walkie-talkies listening to the updates from the accompanying security teams. Both the Syrian and Israeli delegations were driving around the site waiting to be sure the other would turn up.

Finally, both groups arrived, and were saying to each, “It looks like this is going to happen.” Then the Syrians were in the room and the Israelis are walking into the room. The last thing anybody saw before the door was closed was the two sides reaching across the table and shaking hands.

I can tell you there wasn’t a dry eye in the place. We were all overcome with emotion. It was the beginning of a process that went on and made progress on various levels, not just between the Israelis and the Palestinians but between the Israelis and a broad range of Arabs. This process was the real accomplishment of Madrid.

It’s true there was a genuine coalition that was a part of the Gulf War. It was a coalition that was born with the invasion of Kuwait. But don’t forget there was a long period of time between the invasion in the summer and the January 15, 1991 deadline established by the Coalition when we were hoping that the resolve demonstrated by Desert Shield would bring the Iraqis to their senses and begin a process of negotiation.

We were all quite hopeful that something positive emerge in that dramatic meeting between Jim Baker and [Iraqi Foreign Minister] Tariq Aziz had in Geneva. That night I was at a dinner party in Cairo and everybody got up from the table to watch on television the press conference that followed the bilateral meeting.

Of course, we were all crestfallen to hear that no progress had been made. We were no closer to a peaceful resolution of the crisis than before that meeting. Everybody at the dinner part agreed: This means war.

Q: I would think your job would be to try to keep this from looking confrontational while the reporters would almost try to see if they can get something going because it makes for a better story.

KEITH: In this case, the media extravaganza – and I do mean extravaganza – at the Madrid Peace Conference was as much the story as what the principal delegates were saying. The story was not what was going on behind the scenes and it was not really the differences between the organizations and the delegations.

The story was that the damn thing was happening at all and that a broad meeting between Arabs and Israelis was unfolding before the eyes of the world. It wasn’t the differences, because those differences were quite well known.

But the story was about whether or not a process could really be launched. In fact, that is what happened. The inside pages of the story were the human confrontations or the encounters between various members of various delegations – the Palestinians and the Israelis, the Syrians and the Israelis. There was not really much that the press could report of substance in the discussions because not much of that was revealed. But the fact that Madrid was happening, that Madrid was the beginning of a process, was the story….

“The beginning of an important process”

[There were no problems] with the Soviets. And not really with the Israelis after the first day. On that day we had a problem with signage. The agreement was that the Palestinians were there as part of the Jordanian delegation, a joint Palestinian-Jordanian delegation — a fiction nobody quite believed, but appearances had to be respected.

Well, the Palestinians put up their own signs that said: PALESTINIAN DELEGATION. I went to see the joint delegation leader, the very impressive Jordanian Marwan Muasher (pictured), and said “Come on, Marwan, you know the rules.” He just shrugged and had the sign changed.

We had surprisingly little difficulty with any of the delegations. They all knew that we were there to do our best for them, and the interpersonal contacts were smooth. They understood the ground rules. There was never any real difficulty.

Quite the contrary. You had the delegations cooperating with each other. In one small but revealing incident, an Israeli staff member came to the central supply office asking for fax paper or something similar, and there happened to be a Palestinian standing there who said, “Here, we’ve got plenty.”

Cooperation on that human level, at the worker bee level, was really very good. So, no, we didn’t have any problems at that level. The only mild embarrassment came when the Russians wanted to be heard, they couldn’t just walk out on the street and declare a press conference.

At one point they wanted to be scheduled in the main press room and we simply ran out of time. We couldn’t give them any of the marquee locations, so they eventually had to find an empty room elsewhere in the building with just a handful of journalists. But they wanted to be helpful, so accepted the situation with good grace. As far as I could tell, their voice was never heard in the international arena.

Q: You thought when you left there that this had been a successful meeting. It was kicking off a process which in a way continues to today.

KEITH: Yes. The working groups that were agreed to – working groups on economics and trade, on environment and environmental cooperation, on political security affairs, these were very promising and actually got off to a good start.

After Madrid these working groups would meet periodically in the various capitals and they would obviously include Israelis, so there was a moment when, for the first time, an Israeli would actually be going to Oman or Qatar or some of the other countries to take part in these working groups.

That was in itself the beginning of an important process. The confidence building measures that started there, even though we’re in a crisis today, probably have a very important role that has developed over the years and still is important.

“A great piece of choreography”

William Andreas Brown, U.S. Ambassador to Israel, 1988-1992

BROWN: On arrival in Madrid, I was given a briefing by Margaret Tutwiler (pictured). She had our places laid out. We were literally seated on a carpet as she went through the scenario with her Southern twang. She promptly and firmly told us exactly where we were going to sit as Ambassadors, what, when, how, and so forth.

It was quite a show and, of course, she delighted in telling all of her interlocutors, not only American but especially Arab and all of the others, that the Royal Palace in Madrid [Palacio de Oriente] is: “The biggest palace in Europe!” She gave us the details as to how palace guards in their traditional uniforms would give their salutes to the arriving dignitaries and how the cameras of the world were all placed.

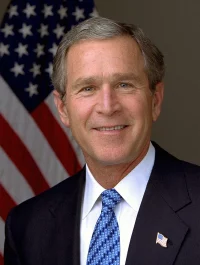

Well, the Madrid Conference was a great show, a great piece of choreography. Full marks to Margaret Tutwiler. President [George H.W.] Bush came, with President [Mikhail] Gorbachev, put in a brief appearance, and used an expression, “territorial compromise.” This was fascinating to me because, like others, I suspected that what he perhaps meant to convey to his Arab audiences was, in essence: “We’ll get you some land, but you’re not going to get it all back.” It would be a compromise. To [Yitzhak] Shamir’s ears, nothing like that was good. He wasn’t particularly interested in any more territorial compromise.

The participating delegations

After months and months of negotiating, what we had in front of us was something beyond the wildest dreams of earlier, Israeli generations. That is, leading an Israeli delegation, Prime Minister Shamir sat in a royal, palatial setting across the table not only from the delegations of Egypt but also of Syria, led by Syrian Foreign Minister Al-Shara, whose vociferous anti-Israeli attitudes were well known.

There was also a combined Jordanian-Palestinian delegation. This was the subject of great controversy, acrimony, and negotiations, between Secretary Baker and the Palestinians, and the Palestinians and Jordanians and everybody else. The Palestinians wanted to be separate, but we wouldn’t let them be separate. Once they were in place, they began acting as independently as they could, anyway. Hannan Ashrawi was now featured, along with Bibi Netanyahu, in the ongoing TV commentaries originating out of Madrid.

For almost the first time the Israelis were meeting formally with their neighbors, including the Egyptians, at an international conference. They already had a peace treaty with Egypt, although it was a cold one. Then there were the Jordanians/ Palestinians. There were the Syrians and a Lebanese delegation which was under the thumb of the Syrians but was seated separately from them, as if it were independent. There, on the side in swirling robes, was a representative of the Gulf Cooperation Council, an Emirate Arab. There was Ambassador Bandar, in his fine robes, a representative of the Royal Family [of Saudi Arabia]. He was the Saudi Ambassador to the United States.

There were also European Community and United Nations observers. Many of these arrangements had been initially strenuously resisted by the Israelis and certain others. Finally, it all worked out. As [famous American comic] Jimmy Durante used to say, “Everybody wanted to get into the act,” once the act had been put together. President Gorbachev of the Soviet Union put in an appearance with President Bush. It was a sweet, yet sorrowful sight because Gorbachev was already on the way down….

“No great breakthrough” but movement on bilateral agreements

The arguments presented were standard on all sides. There was no great breakthrough, in substantive terms. However, a key element here came into play, in the sense that a major part of the choreography was that there would be bilateral agreements reached after the end of this conference, to be negotiated in Madrid.

The Israelis argued vociferously that they should take place in and around Israel. The Arabs rejected this proposal, and a compromise was reached that bilateral agreements would be worked out in Madrid, at least with the Syrians, immediately after the close of the principal conference.

Then, later on, multilateral negotiations would take place on such issues as water, regional and environmental, and economic questions. So there were many breakthroughs in terms of resolving long-standing taboos.

Israeli Prime Minister Shamir turned out reasonably well in comparison with El Shara, who was chief of the Syrian delegation. Shamir appeared to be quite moderate, certainly for Israeli home consumption. The conference was a magnificent TV sight for the world, including Israel, to watch. There were the Arabs with the TV cameras panning around the conference table. There was Israeli Prime Minister Shamir holding forth, as well as [Benjamin] Netanyahu speaking to a worldwide audience to the conference proceedings broadcast from Madrid TV.

[Netanyahu] was Deputy Foreign Minister of Israel and highly articulate spokesperson for the Israeli delegation. He was very, very effective, as was Hannan Ashrawi in her own way, speaking for the Palestinian cause.

A particularly nasty development took place on the last day, a Friday. Prime Minister Shamir took his leave on grounds that, as Prime Minister, he had to be back home in time for the beginning of Shabat [Jewish Sabbath] that evening. He apologized for leaving the conference and expressed the hope that no one would take his departure amiss.

Once he left the conference, El Shara, the chief of the Syrian Delegation, with whom he had crossed swords during the meeting, made a particularly nasty set of comments and held up a “Wanted” poster published during the British Mandate over Palestine identifying Shamir by his traditional, Polish name. It announced a price on Shamir’s head and said that he was wanted as a terrorist. El Shara said that this labeled him forever after as a terrorist.

El Shara said that it was intolerable that this man, Shamir, should be lecturing the conference, given all of the horrible things he had done to Arabs during the years. He said that it was well known that Syrian and Arab hospitality had been extended to the Jews over the centuries. He said that Syrians and Arabs had been the most beneficial administrators of the territories under their control.

For anyone who had even a rough idea of the plight of the Jewish community in Syria, this was a bit difficult to swallow.

So there we were. The Madrid Conference was a great accomplishment in which the Israelis, including Prime Minister Shamir himself, could bask for some time. However, this atmosphere did not last long.

Disagreements on Loan Guarantees to Israel

By September, 1991, just before the Madrid peace conference, President Bush, with Secretary of State Baker at his side, had called for a 120-day delay in reaching a decision over the U.S. loan guarantees to Israel. Bush said that the extension of this loan guarantee was very controversial among the Arabs, who had the mistaken impression that U.S. money would flow immediately to Israel and would be used to build new settlements in the territories occupied by Israel since 1967.

It was such a hot issue that Bush and Secretary Baker said, “Give peace a chance.” They suggested a cooling off period, a delay of 120 days.

Well, AIPAC [American Israeli Public Affairs Committee] and most, if not all of the Jewish organizations in the United States, denounced this linkage between the loan guarantee proposals and the settlement of Russian Jews in Israel. The arrangements for the Russian Jews were specifically designed to settle them in Israel proper, if you will, not the occupied territories. These Jewish organizations took affront. They rose up in protest and gathered their Congressional friends and supporters.

President Bush responded, I believe, on September 12, 1991, at a press conference where he pounded the desk and spoke passionately of “powerful, political forces” arrayed against him. He clearly was referring to AIPAC. He characterized himself as “one lonely, little guy” against these forces, trying to resist them and do his job. He went so far as to employ language about how we had risked American lives in defending the Israelis from SCUD missiles.

The whole situation, taken together, was very, very disturbing to me. It was part of a trend. By now I was coming to the end of my tour as Ambassador to Israel. In conversations with me, Secretary Baker had asked me what I was interested in doing next. I said that I was fully satisfied, careerwise. To me, being Ambassador in Tel Aviv was enough. I said that I would like to stay on till the end of 1991 and then would be ready to go home and retire.

Baker sounded me out as to what might induce me to stay on in the Foreign Service. I mentioned an assignment as Ambassador to Beijing, given my China background. He said, “Well, that’s already spoken for.” I may have mentioned the post of Ambassador to Russia. He said that Tom Pickering [then Ambassador to India] was going to get that. Anyway, Baker said, “How would you like to be Assistant Secretary for Political-Military Affairs in the State Department?” He said that there was a large number of buttons on his phone, and I would have instant access to him.

I said, “Thank you very much for the offer, and I’ll think about it.” However, I had already made up my mind on the spot, “No way would I accept this position.” I did not want to work for Secretary Baker in the capacity of Assistant Secretary or, indeed, in any other capacity.

So I soldiered on as Ambassador in Tel Aviv through the end of 1991. The loan guarantee issue sharpened, the Intifada was significantly reduced as a controversy, but there were some horrible murders taking place of Israelis. One always has to emphasize that many, many more Palestinians lost their lives in the Intifada than did Israelis.

The worst sufferers in this whole process were Palestinians.