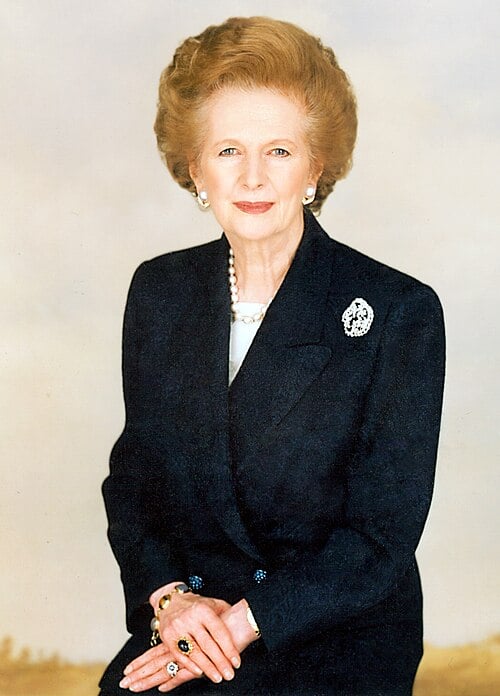

In September 1982, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher went to Beijing to begin a dialogue on the issue of Hong Kong, a small nation that had been a colony of Great Britain for over a century. At issue was the 99-year lease which gave Britain authority over the islands was set to expire in 1997, raising a host of questions on what the future of the territory would look like. In 1984, after two years of negotiations, a Joint Declaration was released in which Britain agreed to cede Hong Kong at the expiration of the lease, while China guaranteed to allow the small nation to maintain an amount of political autonomy under the “One Country, Two Systems” policy.

During the talks, Thatcher later said that Deng Xiaoping, Chairman of the Central Advisory Commission of the Communist Party of China, had told her bluntly that China could easily take Hong Kong by force, stating that “I could walk in and take the whole lot this afternoon,” to which she replied, “There is nothing I could do to stop you, but the eyes of the world would now know what China is like.” Not surprisingly, for those living in Hong Kong during that time, there was a great amount of concern as to what the future would hold.

Dennis Harter, Chief of the Political Section at the U.S. Consulate in Hong Kong from 1982-1984, discusses the issues involved in the handover and how the U.S. quietly tried to help with the negotiations by encouraging an exchange of ideas. He was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy beginning in 2004.

Go here to read Part II on the events surrounding the formal handover. For more information on the important role the Hong Kong Consulate had played in China Watching during the Mao years, follow the link here.

“There was very little cross fertilization of ideas and very little common ground of policy understanding”

HARTER: No sooner did I get to Hong Kong in 1982 than British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher made statements about the return of Hong Kong to China and she traveled to Beijing to propose the start of negotiations between Britain and China over the return of Hong Kong to PRC [People’s Republic of China] sovereignty.

The talks began in 1982, but the actual return date was 1997, 99 years after the lease of the New Territories. This marked the first time the USG [United States Government] was looking at the situation in Hong Kong as something other than a question of textile imports and quotas.

Previously, that was the only real issue in our relations with Hong Kong, although we of course did deal with refugee issues, first the refugees from China and then the refugees from Vietnam. But these were largely “international” issues in Hong Kong and while they had an impact on the local population, they weren’t really Hong Kong issues…We had never been involved with the education system; we’d never been in to talk to people in the local councils or the district administrations. Politically, we were starting out at ground zero.

It was a bit ironic, I had been brought back to Hong Kong to try to rebuild the ConGen’s [Consulate General’s] China reporting credentials and we now were starting an entirely new focus on local Hong Kong issues and the bilateral negotiations between China and the UK.

On the negotiations issue, the basic USG policy was to stay out of the negotiations and to urge both sides to keep the stability and prosperity of the Hong Kong people at the forefront of the negotiations. We did not want to take a position that favored one side or another, but in reality it was very difficult to avoid being seen as supportive of the British negotiating position.

And so, while U.S. officials tried to maintain an impartial stance, the PRC regarded our intentions with some suspicion. The British and the Chinese were often at loggerheads and there was a real dearth of contact among the various players in Hong Kong who represented concerned elements in the negotiations.

This included the two direct negotiation partners – Britain and China – but it also involved a variety of very diverse groups in Hong Kong. These groups would often vilify one another in the media and they advanced arguments about Hong Kong’s future in stove pipes [separate channels of discussion which do not share information with each other].

There was very little cross fertilization of ideas and very little common ground of policy understanding. Because we were out talking to people in all of these groups and getting a variety of opinions about Hong Kong’s future, it seemed remarkable how little the various people talked to one another.

After several weeks of the Section producing reports on a variety of these separate views on Hong Kong, I decided to try a little cross-fertilization. After hearing my ideas, [Consul General] Burt Levin and his Deputy, Dick Williams, authorized me to try to put together small dinner parties that would assemble some of these individuals and try to get them to communicate.

Burt decided not to participate so as to lessen the image of this being a USG-authorized function and we decided we were likely to get higher level attendees if the Deputy CG was the host rather than the head of the Political Section. I wasn’t certain we could get the individuals to come to the same table, even if it was a dinner table, without risking some thoughts that we were “interfering.”

It was also possible that once the people gathered there would be no real conversation and we’d never have a second opportunity to try this approach. But, we went ahead with the plan and brought representatives from NCNA [New China News Agency (Xinhua)], the British Foreign Office representatives in Hong Kong, Hong Kong Government executive and legislative branch officials, academics, journalists, local government administration representatives and business leaders to the table.

It didn’t take us very long to get the conversation started and the guests were quickly speaking out on their views of the Hong Kong situation. The participants soon found areas of common ground even as they articulated confrontational views on a variety of topics related to Hong Kong’s future.

The first dinner proved to be very successful and both the NCNA and UK Foreign Office people from Hong Kong expressed how useful they thought it was for them to hear differing views in a non-political setting. Other participants were equally enthused and the word got out about the dinners so we never had a problem finding willing invitees, eager to participate in the discussions.

We were able to bring different participants together on three or four more occasions over the next few months as a way to encourage more dialogue among those with direct interests and roles in Hong Kong’s future.

Although I don’t know if anything came up in those sessions which made its way into the “Final Settlement”, I do know we had discussions of a number of very controversial issues that as they progressed became less combative and more nuanced and blended among the representatives of the two sides. The next day, I would write up these sessions in reporting messages back to the Department.

Escape contingencies

Almost from the start of the Sino-British talks on Hong Kong’s future, many people [who had emigrated from the mainland] or who were associated with the Hong Kong government were making plans to find alternate residences abroad….

The people who left Hong Kong in this time period got themselves documented in Canada, in Australia, the U.S., Europe, etc and then they came back to Hong Kong to live and work. With their futures secured by foreign citizenship or residency rights, they much preferred living in Hong Kong than they did in Vancouver or New York, or Houston, or Los Angeles or any of the other places they obtained residency.

This was a time too when a variety of places sprung up as instant citizenship meccas where you could, for a $50,000 contribution to the government of the Maldives or a $75,000 dollar contribution to the government of Tonga, become a citizen of those wonderful places. Actually, in most cases it was a lot more than $50,000, but the idea was to attract financial investment to some of these mini-states in return for citizenship.

In some cases you had to wait a period of time after depositing your money, but in other places you could get a new passport virtually immediately after making that basic financial commitment. A lot of the more wealthy people had done this years earlier and at this time it was the middle class people who went out and established rights of abode in other countries….

We made it clear to the [locals] who had been with the Consulate all those many years that the service visa option would be available in Hong Kong. Admin staff members had discussions with the FSNs [Foreign Service Nationals] through the employee association and individually they had their situations reviewed in their various sections. Procedures were clarified and employees understood their opportunities would not disappear so there was no need for a sudden rush to leave Hong Kong.

The Hong Kong government was of course trying to do the same thing and trying to avoid the hemorrhaging of its experienced personnel. The people who had the biggest concern, of course, were the people in the police and those who had been in the correctional institutions who felt they would suffer at the hands of the locals once they were no longer part of the official government system.

Words matter

In the two years I was in Hong Kong, there were a lot of times when public confidence was deeply affected by local perceptions or press perceptions of the degree of progress in the talks about Hong Kong’s future. The Hong Kong dollar went through a number of troughs, the worst of which virtually cut its value by a third in one afternoon, which marked the end of a multi-day session of the bilateral UK-PRC dialogue.

For the preceding sessions, the British spokesperson who reported to the press about the state of the talks had used a formula which was bland but at least positive sounding. On this particular Friday, however, he didn’t use the same formula and the press and the Hong Kong community interpreted the somewhat different comments as the sign of a great failure.

It was probably true that up to that time, this had been a more contentious session between the two sides and there was probably reason to think that the results were therefore a bit of a disappointment to the negotiators. Even though it might not have been as successful a round of talks, however, it would not have hurt for the British to use the same phrases about “frank” and “cordial” talks on that particular occasion. But nobody perceived that a slight alteration in the formulaic public press comment would trigger such a reaction.

The Hong Kong dollar went from something like 6.2 to 1 US dollar to 9.6 to 1 by the end of the day. Prior to this, the Hong Kong Government had been adamant it would not peg the Hong Kong dollar to a fixed exchange rate. But over that weekend, the Governor and his chief financial advisors changed their minds and fixed the Hong Kong dollar at 7.87 Hong Kong dollars to one U.S. dollar and it has pretty much stayed at that rate ever since. [Note: As of 2016, it was at 7.76 HKD to one USD.]

“I don’t think she, or the UK Government, ever told us beforehand that she would open the dialogue”

The British had been very reluctant from the beginning of the talks to share anything with us. That included sharing at our Embassies in London and Beijing and their Embassy in Washington.

But a couple of the Hong Kong British officials, the Political Advisor and his Deputy, both of whom were British Foreign Service officers assigned to the Hong Kong government were accessible. And, within certain guidelines, they did let us have a pretty good idea of where things stood. They were not allowed to go too deeply into details, but in Hong Kong we were able to learn much more about what was going on in the talks than anywhere else. The Consul General, his Deputy and I maintained that particular dialogue with the Political Advisor’s Office.

We had, I think, been as surprised as anybody else by Margaret Thatcher’s proposals to start negotiations with Beijing on Hong Kong’s return to the mainland. I don’t think anybody was focused on it as a significant issue because the lease expiration was still 15 years out.

While I’m sure she’d discussed this with the Foreign Office, one had the impression the initiative was her own. And, unlike a lot of other issues where our special relationship with the UK meant we had very intimate exchanges of information, I don’t think she or the UK Government ever told us beforehand that she would open the dialogue in 1982.

Once that issue was out in the public eye, I am certain we had any number of dialogues with the British urging that they try to negotiate some quasi-separation for Hong Kong from the mainland. But that wasn’t anything special because the UK had as its own chief objective the maintenance of some kind of continued British administrative presence in Hong Kong after 1997.

Quite apart from what the British were doing, the USG was also involved in looking at our own status in Hong Kong after 1997. Would we merge the Hong Kong Consulate with the Consulate in Guangzhou and cover all of south China from there?

Would the Chinese permit Consulates to operate in Hong Kong at all? If the Consulate remained, would we be able to maintain defense attaché officers and ship visitation rights once the PRC assumed sovereignty? We had to determine what to do with the FBIS [U.S. Foreign Broadcast Information Service] operation in Hong Kong and all of its sundry monitoring of broadcast and news information inside China.

We did develop certain contingencies including reducing the size of our staff in Hong Kong and scaling back on our operations. So, there were a lot of those kinds of issues that had to be thought about as it related to the future positioning of a Consulate General in Hong Kong. That was certainly part of our internal focus back in 1982, 1983, 1984, the time period that I was there.

None of these issues was fully resolved before I left in 1984, but later that year the Basic Agreement was in fact concluded and it became clear we would be able to maintain our facilities in Hong Kong after 1997. And much of what we were able to do before 1997 continued to be possible afterwards.

“Washington never shared any of its thinking on the formulation of U.S. policy on this issue”

Part of the problem in this particular time period is we had very little idea what, if anything the U.S. government was doing with the reporting we were sending back. We knew a little bit of what the Brits and the Chinese were doing in the talks and how they might play off some things we had discussed in Hong Kong.

But whether there was anybody in Washington who was really paying a significant amount of attention to this, we really didn’t know. We virtually never got feedback. I mean, people might say about our bringing the various groups in Hong Kong together around the dinner table, “Oh, great idea, good that you’re doing this sort of thing.” But Washington never shared any of its thinking on the formulation of U.S. policy on this issue. I found it frustrating.

Knowing the materials we were providing and the way in which we were putting different ideas into the collective mix for those involved in the negotiations, but we had no idea what anybody in Washington thought or whether they really cared about where the negotiations were going. All we got were a few “atta boys.”

Moreover, NCNA was still staffed by individuals who were really quite minor-level bureaucrats. There was no one of stature to deal with the Hong Kong Governor. But, quite unexpectedly, Beijing sent a cadre with stature, Xu Jiatun, to head NCNA. He was a former Party First Secretary in Jiangsu Province, the province surrounding Shanghai, a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Xu was an effective representative for Beijing, who had clear prominence, was an established party official, and yet he was quickly able to move in the various political circles of Hong Kong.

After Xu arrived, the articulation of PRC policies softened a bit and Chinese pronouncements on Hong Kong’s future featured more assurances to the people of Hong Kong. The presentations were all more sugar-coated. It was all much smoother than in the earlier period where Beijing seemed satisfied just to say “we will be in charge.”

I’m not sure there was any overall change in Beijing’s intentions. Beijing now willingly acknowledged there would be a local administration, some sort of operation which reflected the special nature of Hong Kong and protected the economic system which had sparked China’s most recent economic growth.

But, ultimately, there was no way Hong Kong was going to be allowed to be “independent” and the Hong Kong administration would be a facade that masked Beijing’s ultimate decision-making authority across the political and economic spectrum.

The PRC had to be very careful about how it played all of these public pronouncements and maneuvers, because Hong Kong was only part of China’s territory that needed to be rejoined to the mainland. Taiwan was the principle prize and everything that was being played out for Hong Kong was being watched in Taiwan to evaluate how the Chinese would handle this transition.

And, of course there was a little issue to be dealt with in Macau, the Portuguese colony which had a 1999 lease expiration date, but which everyone knew would follow just behind Hong Kong once that arrangement was completed.