In 1982 a long-simmering dispute between the United Kingdom and Argentina over a small group of islands – the Falklands for the British, the Malvinas for the Argentinians – erupted into war. The disagreement arose from a dispute that goes back to the 1700’s when France, Spain, and Britain all tried to claim and settle the islands (with France selling her claim to Spain). Britain and Spain almost went to war over the archipelago before coming to a compromise that while neither recognized the claims of the other, they would not interfere in each other’s settlement activity. Eventually both sides abandoned their outposts due to the economic pressure of supporting the distant, windswept islands.

Businessman Louis Vernet began a settlement in 1829 as a business venture with the permission of the new Argentine government, which had inherited the Spanish claim. After a series of disagreements and violent incidents among several parties that involved the near destruction of Vernet’s settlement by an American warship (the U.S. did not recognize the claim of any country over the islands at the time) the British reestablished authority in 1833 and brought in settlers whose descendants make up most of the current Falklanders.

During the post-WWII populism of Juan Peron, Argentina began to raise the issue again. Britain told Argentina that there was no hope of an eventual transfer. Seeing no diplomatic way forward, the Argentine military junta launched a surprises attack on the Islands in April, 1982. Within three months the British retook the islands.

Here are the stories of two American diplomats who served in each country at the time of the Falklands War. First we read the account of Phillip Pillsbury, Cultural Affairs Officer in Argentina between 1980 and 1984. He was interviewed by ADST founder Charles Stuart Kennedy in February 1994. Roger G. Harrison served as Deputy Political Counselor in London from 1981-1985. He was interviewed, also by Kennedy, in November 2001.

To read more about colonial disputes, South America, the United Kingdom, or another account of the Falklands Crisis, please follow the links.

“To the surprise of everyone, Margaret Thatcher said: ‘We’re going to come and take them back’”

Phillip Pillsbury, Cultural Affairs Officer, U.S. Embassy Buenos Aires, 1980-1984

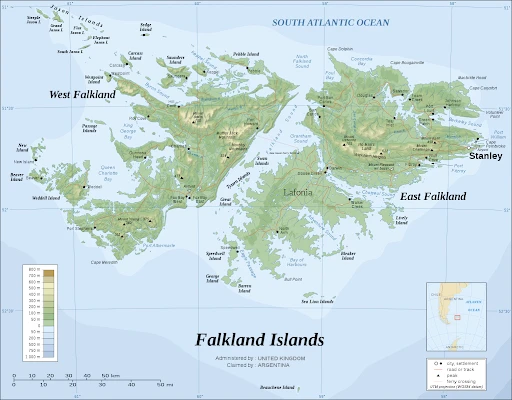

The Malvinas, or as we called them, the Falklands, are islands off the coast in the South Atlantic that are now owned by the British but have been claimed by the Argentines for a hundred and thirty-three years as theirs. In terms of value, as real estate there is probably very little. Many more sheep on the islands than human beings.

There is indication of oil resources off the coast that have not yet been explored, probably true. But it was more a spiritual and historical and traditional thing for the Argentines and their claim is valid. It is shrouded in counterclaims that go way back. Even the United States was involved at some time…

Our action, the U.S. Navy action in 1828 or 1830, enabled the British to establish their hegemony over the islands. But since then, there is a song that school kids sing in Argentina referring to “our sisters the Malvinas,” so that it is part of the national psyche, and was a constant thorn that existed in the love/hate relationship that has existed between the British and the Argentines, given the fact that there is a very large British community down there. It came to a head in 1982.

There were three major misconceptions that led to the outbreak of that. One was that the British didn’t really realize how seriously the Argentines felt about this. It was always on the back burner for them and when the Argentines said: “We want to talk about the Falklands,” the British said: “Yes, sometime, but not now.”

The Argentine government, the military guy at the time was a man by the name of [Leopoldo ] Galtieri (seen right.) Galtieri had a mistaken notion about the relationship of civilian and military power in the United States. He had been to the United States just after Reagan’s election, when he was head of the army, and had been feted and made to realize how important the United States felt the army was. He came away with the mistaken impression that the United States would support him in their effort to get the discussions going on the Malvinas.

The third misconception was the failure of the Argentine military to take seriously the British threat to send an armada. I think that everybody was surprised by that. So there were these three misconceptions working when, in the first part of 1982, some Argentines occupied the weather station on South Georgia in the South Atlantic.

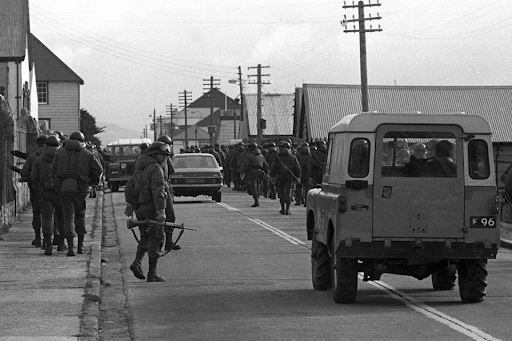

Galtieri at home was facing increasing unrest, and it is a standard ploy as we know for military people, if they’ve got troubles at home, to embark on a foreign adventure to get the people’s minds off what’s wrong at home. So he very secretly laid the plans for the invasion of the Falklands, and I think it was on April 1 as a matter of fact, April Fool’s Day.

To the surprise of everyone, Margaret Thatcher said: “We’re going to come and take them back.”

And the United States, for the first part of that period of seventy or eighty days, tried to serve as a mediator. Haig came down a couple of times. He went to England. Then it became evident that nothing was going to happen.

The British had launched their armada and we obviously sided with the British. We said: “It is still British property.” It was at that point that things got kind of unpleasant in Argentina on an official basis for Americans being there, and certainly for the British. They broke relations, of course, and the British interests section was set up in the Swiss Embassy.

There were elements, certainly official, that felt that the United States had betrayed Argentina. [Harry] Shlaudeman, our Ambassador, was given the cold shoulder not just by the government but by friends who surprised him, doing that to him.

We in a work capacity had to hunker down, certainly. We stopped a lot of our activity. I still traveled some but our public programs were really basically stopped for that period. On a personal basis, friends … there was no change at all in our relationship with the Argentines.

We continued to have a very good personal relationship but we were in cold storage for that period during the war. Feelings in the country were ambivalent towards the United States.

The Argentines, realistically I think, believed that the war reflected the last dying gasps of the repressive military government they wanted to get rid of. But on the other hand, it dealt with something that was very close to their hearts and part of their national patriotic sense. So it was a very hard period for us as Americans and for the Argentines in our official dealings.

“The last thing they wanted was a settlement. They wanted to exact revenge”

Roger Harrison, Deputy Political Counselor, U.S. Embassy London, 1981-1985

[Lord Peter] Carrington was British Foreign Minister when the Argentineans invaded the Falklands. He resigned in disgrace, saying on the way out that it was always little things that get you. Certainly the invasion was unexpected.

But Thatcher was Prime Minister and she was anything but “wobbly.”

So there was never any doubt that the British would respond, if they could. Nor was there any doubt that the United States, Reagan’s United States, would support with intelligence and various other things, which we did.

Since I was the political-military guy, this was largely my issue at the staff level, with Dick McCormack as Counselor taking the lead and Peter Sommer as the OSD [Office of the Secretary of Defense] rep contributing his contacts. Still, special relationship notwithstanding, the British were far from candid about what they were going to do, and in the end lied to us about their willingness to negotiate.

They did. It was the very much the last hurrah. Most the principal ships in that armada were already headed for the scrapyard. It will never happen again, but this one last time it was still possible. And – thanks in large part to Thatcher, who was in her element as the warrior leader – their blood was up.

But there had to be some feint at negotiation, and our Secretary of State, Haig, played right into Thatcher’s hands. He began a shuttle between Buenos Aires (BA) and London. I’m convinced that he was trying to replicate Kissinger’s Middle East shuttle diplomacy.

But Cairo is only an hour from Tel Aviv by air, and BA is 20 hours from London. The White House Staff, who generally despised Haig, made sure that he got the slow 707 without windows that would have to refuel a couple of time on the trip.

I was at Number 10, looking out the window just above the famous door, on one of these trips. Haig, who had spent 40 of the last 48 hours in the air, got out the car looking like death, with his staff struggling out behind him, only to be greeted by Thatcher, fresh as a daisy, beautifully made up, hair coiffed.

It let her look like she was negotiating, and Haig may even have thought she was. He wasn’t the brightest bulb ever to adorn the national security tree. But the MOD [Ministry of Defense] and FCO [ Foreign and Commonwealth Office ] people were making clear to me and others that the last thing she would do is march her army up the hill and march it down again.

They took this pretense of negotiation as far as telling my colleague, Peter Sommer, that when the armada arrived off the Falklands it would circle around giving another chance for negotiation. He wanted to report that, but I fought against it.

As soon as they got there, I argued, they would attack. It would be a practical necessity, since an army three weeks at sea is going to degrade rapidly. And the last thing they wanted was a settlement. They wanted to exact revenge. I lost that battle, but I was right. They had lied to us about the date. As soon as they arrived, they attacked. (The HMS Sheffield, fired upon, is at right.)

What other memories of the Falklands? Carl Bernstein came to town, reporting for one of the networks. Someone told him that I was the guy who knew about the Falklands, and since British officials wouldn’t tell him anything, he took to buying me beers and calling me at home.

He’d come up with something, call me and do that thing Dustin Hoffman did in the movie about Watergate. He’d say, if this information is correct, don’t say anything for 10 seconds.

And I’d tell him it wasn’t going to work. I’d seen the movie.

Once he called me at home when we were giving a dinner party and my daughter answered. She told him we had guests, and – like a good reporter would – he asked her who they were. In fact, I didn’t know most of what he was asking me about, but he didn’t believe that, so we had an intense and brief acquaintance. I guess I was also impressed with how some people resemble the stereotypes we have of them.

Bernstein was exactly what I’d imagine him to be. Richard Hastie-Smith, an undersecretary at the MOD, who wore pinstripe suits and a watch fob and stuffed his hanky up his sleeve as all good graduates of some Cambridge College do, looked like he’d come from central casting.

And, come to think of it, I was the bumptious and embarrassingly open American yokel who had to be jollied along. So, we all lived up to our roles. It was a near run thing for the British, wasn’t it? It was close.

The Exocet anti-ship missiles had just arrived and the Argentine pilots hadn’t been able to practice with them. (Argentine pilots seen at left.) Plus the armorers got the fusing wrong. Otherwise, the armada would have been toast. As it was, the British lost a number of ships.

But there were several cases in which Exocets passed through ships without exploding. When they did explode, it was all over, because it turned out the aluminum in superstructures burned. We found out the same thing later with one of our cruisers hit by an Iranian missile in the Gulf.

One incident from that time. Rick Burt came out to consult. He was Assistant Secretary for EUR [the State Department’s Bureau of European Affairs] then, and he told the FCO leadership how he’d been well informed about events from CNN. I piped up from the back row when he said this and added in a stage whisper: “Not to mention the insightful reporting from the Embassy.”

It got a big laugh, but we were laughing past the graveyard. CNN had showed up in everyone’s office by then, and that’s where policy makers got their info. Nobody was reading our stuff. We’d seen the future.

I would argue that no single diplomat, or any group of them, has had the influence Wolf Blitzer has had on Washington perceptions in decade since.

I was in Parliament when Thatcher gave her victory speech. Churchill’s history of the Second World War has that line: “In victory, magnanimity.” Thatcher must not have read it. She had been staunch, done the right thing, and magnanimity be damned. Went over well.