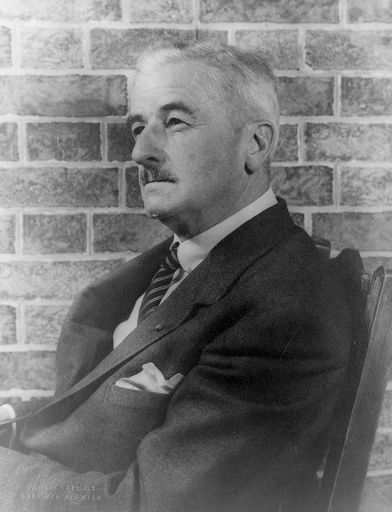

William Faulkner, among the most decorated writers in American literature with the 1949 Nobel Prize for Literature, the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and the National Book Award among his honors, was invited to Japan in 1955 under the auspices of the Exchange of Persons Branch of the United States Information Service (now consolidated into the State Department.) He was to speak at the annual Seminar in American Literature the U.S. Government sponsored for Japanese teachers of English language and literature in the mountain resort town of Nagano, then give lectures in other venues.

Enthusiasm for Faulkner in Japan was based in part on his stature in world literature, strengthened by parallels between Faulkner’s writings about the defeated South and postwar Japan, recovering from its massive losses in World War II and its rebuilding under the administration of a foreign army. Faulkner’s visit generated tremendous interest, but its overall impact was limited by his inebriation and subsequent inability to interact with some of the Japanese and American interlocutors he had been brought over to meet.

G. Lewis Schmidt, who was the Acting Public Affairs Officer in Tokyo, recounted his experiences with Faulkner in an interview with Allen Hansen in February 1988.

Please follow the links to read more about cultural diplomacy, Japan, another perspective of the William Faulkner visit to Japan by Leon Picon, or G. Lewis Schmidt’s oral history.

“Mr. Faulkner is here and there are some problems”

G. Lewis Schmidt, Acting Public Affairs Officer, United States Information Service Tokyo, 1952-1956

SCHMIDT: In the years after 1953, the Exchange of Persons office in Washington furnished name figures of American literature to perform as discussion leaders at the seminar. The most famous of these was William Faulkner, whose participation in 1955 made headlines all over Japan, and whose visit provided one of the most memorable set of events in my career . . .

William Faulkner [was] the person who was sent out from Washington under the Exchange of Persons Program in 1955 to be the moderator of the Nagano Seminar (Nagano is seen at left.) We had thirty-two Japanese professors of English at that meeting.

The competition for participation in that year’s session because of Faulkner was tremendous. He had won the Nobel Prize a few years before and was a legend in Japan among those who knew anything about literature. His coming was highly heralded.

I’ll not go into all the details of Mr. Faulkner’s visit. But nobody in Washington had told us that he had trouble with alcoholism. When he arrived and got off the plane after a twenty-two hour flight from the States, he obviously was under the weather.

I was in Nagano handling the first stages of logistics and setting up the arrangements for registering all the professors and getting the seminar ready to operate, taking care of the hotel facilities and what not. I got a call from Tokyo saying, well, you better come back. Mr. Faulkner is here and there are some problems.

So I left Nagano and got back to my office the next day. Leon Picon, who was our book translation officer and assistant cultural attaché, had been designated as the man to meet Faulkner. Leon was going to be the resident American from the embassy at the seminar in Nagano because of the fact that he was deep into the book program.

Well, Leon was pretty resourceful. He, of course, had come out in an embassy car. When he got Faulkner off the plane and realized his condition, he managed to get Faulkner back to the International House, which a few years earlier had been established under Rockefeller Foundation auspices.

John D. Rockefeller III had made sort of a career of charities and ran the Rockefeller Foundation. He was a Far Eastern specialist himself, had given a large grant of money to the Japanese government and the Japanese cultural operations to set up this International House, which still exists and is an extremely important part of the cultural and exchange program with America today.

It is completely independent of the embassy, but the PAO [Public Affairs Officer] sits on the board of that center while he’s active in Tokyo, and for years it housed the Japan Fulbright Commission offices.

The House (seen left) has hotel-like facilities for visiting cultural personages staging cultural conferences, providing study space for visiting scholars, etc. It’s sort of an exclusive hotel arrangement. They even have their own dining room. Leon got into a conversation with Faulkner who, despite the fact that he was quite inebriated, handled his liquor fairly well.

He was just a charming person, a real southern gentleman, polite, gracious, absolutely a delightful individual. But, of course, somewhat slurred in his perceptions when he was having this difficulty.

He finally confided in Leon, who had a great capacity to establish rapport with people quite quickly. On the way in to the International House he virtually broke down and almost tearfully said that he did have a problem with alcohol. And he was going to rely on Leon to keep him at least relatively sober so he wouldn’t disgrace himself.

So Leon said, okay. By this time they were on the Leon and Bill basis. He said, why don’t you, Bill—Faulkner is Bill—why don’t you let me have any liquor you’ve got with you? He said “I’ll do that.”

When they got to the International House he opened a suitcase which was full of bottles of gin, and gave all the visible bottles to Leon who took them away and sort of tucked him in for the night. Leon said, well, we’ve got a program starting at 9:30 when you have an appointment tomorrow morning with the ambassador. I’ll come by and pick you up about nine o’clock or a little before in the morning. See you then. He then took off with his armload of gin bottles.

Leon went back to pick Faulkner up the next morning. And Faulkner had obviously secreted some liquor elsewhere in his luggage, because he was once more pretty well under the influence and was stark naked, wandering around the halls of the International House in the altogether. Leon got him back in his room and they got him dressed. Leon phoned me.

By this time I was over in the ambassador’s office waiting for them to arrive. I think the appointment was actually at ten o’clock. This was about 9:30. And he called me in the ambassador’s office and said that he was having a little trouble, but don’t worry. They would get there.

Faulkner and he arrived about fifteen minutes later. The International House is not that far from the embassy. Faulkner had sobered up a little bit but not all that much, and he plunked down in a great big overstuffed chair, not very communicative.

The ambassador’s number two secretary, a young girl who was in her first overseas post came over and said, very awed at having Mr. Faulkner, a Nobel Prize winner there, and said, “Mr. Faulkner, can I get you a drink?”

And he said, “Yes.”

And she said, “What would you like? Water?”

He said, mischievously, “No. Gin.”

The poor girl was completely nonplussed. She retreated in confusion, but did bring him a glass of water. At about that time the ambassador showed up at his outer door and said, “Okay, come in, Mr. Faulkner.”

Bill couldn’t get out of the chair. So Leon and I hoisted him out and each one got under an armpit. We guided him into the ambassador’s office and sat him down. The interview proved to be a disaster.

The ambassador didn’t immediately recognize that he was almost incommunicado. And he began directing a few questions at him to start the conversation. Faulkner’s responses were at least uncommunicative, usually about two or three words or yes or no or something like that. And it soon became obvious that he wasn’t going to be able to make a successful interview at all.

I could see the ambassador getting very fidgety. So I finally said after about ten minutes, “Well, Mr. Ambassador, we thank you very much for your interview. We’ll leave now because we don’t want to take up more of your time. And we’ll see you this afternoon.”

The ambassador had agreed to give a party for him at the residence to which we had invited quite a large number of the American press, some of the cultural big wigs of the Japanese government and some from the universities.

So again, Leon and I hoisted him out of the room and we got him over to the Embassy annex where the USIS [United States Information Service] offices were and into the office of Don Ranard, the head of the Exchange of Persons Program.

“Now, don’t give him anything alcoholic to drink”

Well, Bill was supposed to speak to the foreign press club at 12:30 that day and didn’t look like he was going to make it. Leon and I stayed with him trying to get him sobered up in the meantime. However, I wasn’t sure he was going to make it at all. He kept passing out.

So I got hold of my wife by phone. She was a nurse. She came over with a lot of antidotes for fainting and that sort of thing plus our air mattress which we blew up and put down on the floor and got Bill stretched out on the mattress.

Meanwhile, Leon went down to the press club and tried to pacify the press. As 12:30 approached, when he was supposed to speak, everybody wanted to know where Faulkner was. Leon kept phoning back reporting on the situation, and we kept reporting to him that we weren’t sure Faulkner was going to get there. But Faulkner kept saying, yes, I’ll do it.

So we told Leon well, maybe we’ll get him down there but we’ll be a little late. Finally about 12:30 when he was due at the press club he sat up straight on the mattress, but promptly threw up all over himself and all over the floor. And that immediately, of course, meant he wasn’t going to get to the Press Club.

So I got hold of Leon, who had the outline of remarks that he had made for Faulkner to speak from. Faulkner was terrified of speaking anyway. He hated public speaking. And Leon had to give a talk.

The Press Club audience was infuriated. There was an article that appeared in Time magazine the next week, next issue, saying that Faulkner had chickened out and come inebriated to Tokyo and hadn’t been able to perform. And that while the press club was filled with people who’d come in from all over the Far East to listen to him, Faulkner “was bedded down with a nurse somewhere in Tokyo” which was, I guess, literally true, but not the implication that they meant, my wife being the nurse.

So anyway, we had to take him up to our apartment in the Embassy compound. Leon went up and got a fresh set of clothes for him up at the International House. We got him in the shower, washed him off, put him to bed for an hour or so, then got him up around 4:00 p.m.

He got dressed in his fresh clothes and really had come out of it pretty well by that time. We had a lovely conversation with him. Wonderful guy when he was sober. My children came in, met him and got his autograph. He was gentle, gracious, kind.

We got him up to the ambassador’s in time for the reception, around 6:30. I told the waiters up there, “Now, don’t give him anything alcoholic to drink.”

I had no sooner gotten him into the receiving line . . . [when] the waiter handed him a very tall and strong gin and tonic. I glared at him but I didn’t want to make an issue because the guests were already coming in. I made signs not to give him any more.

But Faulkner began bowing over the hand of every woman who came in and bowing very low in his Southern fashion and kissing her hand. About that time another waiter brought in another gin and tonic. (Ambassador’s residence in Tokyo at right.)

I watched Bill carefully. He hadn’t completely recovered from the morning. So I knew that this was going to be damaging. But I couldn’t take it away from him. Every time he bowed he bowed lower and lower. I was afraid he might collapse face forward on the mats.

And as soon as all the guests had arrived or most of them I got him out of the line and we put him over at a table nearby. This was in the main reception salon of the ambassador’s residence. Several tables were placed around the hall. Mrs. Allison [Minta Dott Sue Allison, wife of John M. Allison, United States Ambassador to Japan, 1953-1957] came over and sat down, and started to converse with him. By that time they’d given him another gin and tonic, a brand new one.

Fortunately at least, he was by this time in conversation with Mrs. Allison, and wasn’t drinking it. Well, I don’t think they’d been talking more than three or four minutes when Mrs. Allison asked him a question. Strangely enough, although he was a little tipsy he was still quite rational.

He was explaining something, and suddenly he swung his arms open in a wide gesture, knocked over this tall gin and tonic and it all drained over into Mrs. Allison’s lap. She was wearing a brand new specially-tailored Chinese brocade that the ambassador had ordered for her from Hong Kong and had been done by her dressmaker.

The drink splashed all over her new suit, cocktail suit. Obviously, she was very angry and so was the ambassador.

“I want you to give me one good reason why I shouldn’t put this character back on the next plane”

All in all it didn’t make for a very successful party. We had to stay a while. But I finally got Faulkner out fairly early. The party broke up. We took him out to the Army officer’s club and fed him a good meal. That sobered him up a little bit, and we took him back to the International House.

The next morning the ambassador (John Allison, seen left) sent me a letter by courier, saying, I want to know what idiot in USIA or the Department of State ever thought of sending this lush, this drunk over here to participate in a nationally-advertised seminar.

I want you to give me one good reason why I shouldn’t put this character back on the next plane to the United States and cancel his whole visit.

That was about ten o’clock in the morning. Of course, all the professors had arrived at Nagano waiting for the great personage to show up. And I debated what in the world to do to satisfy the ambassador…

I wrote back and I said I was very sorry all this had happened, that I had no idea that anything like this would occur. And I had thought I would be able to deliver to him a perfectly sober Nobel Prize winner.

But I felt that we couldn’t send him back now and terminate the program as far as we were into it—that I thought we could keep him under control and he would make a great contribution. I hadn’t heard anything back when the work day ended.

It happened to be the day on which the ambassador was giving a big party for the embassy staff. He did this two or three times a year so he could get closer and more familiar on a friendly basis with his staff. The embassy population was pretty large, and when I got there the party was already well underway. I could tell by the decibel count that several drinks had already been served.

When I got up to the party, which was being held on the roof garden of the apartment in which I was living in the embassy compound, the ambassador was there in an aloha shirt and in a fine mood. He had another drink in his hand. I went over to him wondering what in the world I was going to get as a response. (Faulkner seen with a Japanese professor at right.)

And he said, “Lew, you were right.” He said, “I lost my cool. I’m sorry. The guy can stay. But I’m going to hold you responsible and he better perform all right.”

Well, Leon managed to keep Bill under control, not always, but for most of the time he was a relatively sober guy. His performance in Nagano was tremendous…He was vastly successful in making a tremendous impression on the Japanese who were there. He got excellent press as we mentioned earlier.

Harry Keith stage managed a picture called “William Faulkner in Japan” which was beautifully done. It was narrated by a then JOT [Junior Officer in Training], who now is the PAO in Tokyo, some thirty years later, Jack Shellenberger, who had been a radio announcer before he came into the USIA program.

All in all it was a tremendous success. After Faulkner had returned to the States, we were having a staff meeting, the first ambassador staff meeting after Faulkner’s departure. I reported that the Faulkner visit was over and that it had gone very well, that we had had a great response, that the press reports were all favorable, and the Japanese were enchanted and what not.

So Andy Kerr, the rather cynical number two man in the Economic Section said, “Well, was it because he really was all that good? Or was it just because he had a big name having won a Nobel Prize?”

I didn’t think very fast. And I said, well, it was a little of both. But anyway, his was an effective program. Afterwards, I thought what I really should have said was: “Andy, you’re missing the whole point. It doesn’t make any difference what the reason was.The fact that he got that kind of coverage and made that kind of an impression was the important thing. And it was a tremendously successful program.”

But I wasn’t quick enough on the trigger to have said what I ought to have said. At least it was a successful program.