With forged passport in hand, Kathleen Stafford donned fake eyeglasses and pulled her long hair back. If this plan worked, she would finally be free. Kathleen, a foreign service spouse, had been in hiding for the past three months. On November 4, 1979, Islamist revolutionaries attacked the U.S. embassy in Tehran. Smoke billowed from the building, shattered glass peppered the floor, and many embassy personnel were led out of the building blindfolded and bound. Through luck and quick thinking, Kathleen and a small group of fellow Americans managed to evade capture, but they had no way to leave the country. Fortunately, the Canadian ambassador agreed to hide Kathleen and her companions until the situation cooled down. But when days turned into weeks, it became clear that the new Iranian Islamic Republic was not going to free the hostages, and would continue to look for the escapees.

One day, a CIA officer showed up under alias “Kevin Harkin” to relay the final plan for escape. Kathleen and the other Americans would pretend to work for a Canadian movie production company. “Harkin” gave them business cards, a magazine with an advertisement for the movie site, and disguises. As a final step, the group “tossed everything we had from the USA, everything we owned that had any sort of American brand on it.” Then they headed for the airport, and after many tense moments, they made it onto a commercial flight. Meanwhile, the Canadian ambassador closed his mission and quietly escaped. This story was later captured in the 2012 movie Argo, which won Best Picture at the Oscars.

Although she was physically unharmed, Kathleen bore the mental toll of the Iranian hostage crisis for a long time. It would take another year for the remaining American hostages to be released. Kathleen frequently dreamt that she was on a plane, and “the other hostages would be on the plane, but they wouldn’t talk to me.” Once an avid painter, Kathleen found that “everything I’d paint, I’d ruin.” She concluded that this was all the result of survivor guilt. When the hostages were finally released, Kathleen flew to Italy to meet them and express her joy that they were finally free. The dreams stopped and she began painting again.

Kathleen Stafford is the spouse of Foreign Service Officer Joe Stafford. They married in 1972. Seven years later, they were stationed in Tehran, immediately before the Iranian hostage crisis. She also worked as an art teacher for several years, and continued to paint. Joe retired from the Foreign Service in 2014.

Kathleen Stafford was interviewed by Marilyn Greene on November 14, 2012.

Drafted by Amelia Bowen and Elise Bousquette.

Read both of her oral histories HERE and HERE.

To read more stories about the Iranian hostage crisis click HERE, HERE, and HERE:

Excerpts:

“We waited for things to settle down, and it didn’t look like they were going to settle down.”

The Consulate is Attacked: We had been working in the embassy. And that particular day was the first of the week. The day before the embassy had been closed, and demonstrators had come by and written things on the wall, “Death to America,” “Death to Jimmy Carter.”

. . . . So we were in the Consulate, and by mid-morning, we heard noises and yelling that there are people running around on the compound, with sticks and rocks and things. Somebody yelled, “Shut the door!” But Don Cooke from our A-100 class was outside. He was getting us croissants. And so as soon as he ran in, I shut the door. I remember shutting the door. And then we waited for things to settle down, and it didn’t look like they were going to settle down. More and more people kept coming on to the compound from the little bit we could see. And so somebody said, “Go upstairs,” because that would be one level up and quieter. . . .

I was quite sure that nothing would happen, because this consulate had just been reinforced with bulletproof glass everywhere. And I don’t know how much money, maybe two million dollars, which was a lot back then to make it, you know, safe. So I was saying, “No, it’s going to be okay.”

Bob Morefield, the Consul General, our boss, called the police and said, you know, “We’re having trouble here. You need to send somebody over.” And I think they just hung up on us. So after about an hour or so the local staff were looking very nervous. They were crying. Some of them took off their ID cards and tossed them behind the file cabinets, because they knew it’d take a long time before anybody found them there. . . .

[Then], someone threw something in through the bathroom window, I guess that had not been reinforced. The Marine, Sgt. Lopez, tied the doors of the two restrooms together with a coat hanger to delay anyone trying to get in that way. Then someone thought they smelled smoke coming from the roof so we thought we should try to leave out the backdoor where the visa applicants always come in. At this point—this was only a takeover by the students/militants and nobody else was in on it. So the local revolutionary guards, who were usually posted outside our door and they were armed, weren’t in on this takeover. So they were just standing there guarding their post.

“There were only Farsi speakers on the radio and so we knew that meant everyone at the embassy had been captured.”

A Desperate Escape: Rich Queen, who was also in the A-100 course with [my husband] Joe and [fellow FSOs] Mark Lijek and Don Cooke—went out and said hello to them. And they didn’t say much, they said hello. And so then we started leaving. So first were the Iranians who were there for their immigrant visas, and then the FSNs, and finally the Americans. We were going to split into two groups. A local employee, a young woman who offered to show us the way to the British Embassy since we didn’t know its location. And that was our safe haven goal. The marine, Sergeant Lopez, had torn off all his insignia and threw on the janitor’s jacket to hide his uniform. So we left separately, they turned down one street we went another way. As we were making our way toward the British Embassy we saw this huge mob of people coming from that direction. . . .

[W]e realized we were not going to make it to the British Embassy and [Fellow FSO] Bob Anders said, “I think I’ll go home and I live close by. Do you want to come with me?” And we had been there two months and we knew nobody but a few Iranians who we could not possibly ask for help.

So we said, “We’re going with you, Bob.”

We separated a little bit more to be even less noticeable. There was one roadblock, a Revolutionary Guard headquarters office, that we had to walk by. So we crossed two at a time. And we got to Bob’s house. And started listening to the embassy radio, you know, everybody had a radio in their house, we could hear that the Americans talking and the Iranians militants too. Finally we could hear that they got . . . to the vault, that is, to the classified area. And we could hear that they had gotten in. Finally, there were only Farsi speakers on the radio and so we knew that meant everyone at the embassy had been captured. We called the British Embassy to see who had made it there. And there was only one local employee who was hysterical really. So then we started calling around to the different places. There was an apartment building where some of the Marines and TDYers [temporary duty military personnel] stayed. . . . We called Kate Koob, the cultural affairs officer who worked at the USIS (United States Information Service) Office at the Iranian American Cultural Center, which had not been attacked in February. So Kate was thinking, “Well, we’re not considered part of the embassy by these students so nobody’s going to bother us. So we’re just fine.” So she and her deputy, Bill Roper stayed there, and they opened a line to Washington. And they were talking to people in Washington.

“People were really courageous to offer us help at that time.”

Eluding the Iranians: When [our USIS hosts] Kate and Bob woke up in the morning, they said, “We’re fine now. We can take over again.” Now, all along we’re thinking, you know, this isn’t really going like it did back in February [when the staff at the U.S. embassy in Iran were only briefly held hostage]. They’re not freeing our people at the embassy. And it wasn’t looking good. So we thought we better get some clothes and some money. Kate loaned us her driver and we went to the Lijeks’ house and they got some money and packed some clothes and we got some food out of the refrigerator. Their landlady was not a very sympathetic type and they wanted to be out of there in a hurry.

And then we went to our house. And our landlord came downstairs and said, “Can we do anything for you? Can we help?”

And we said, “No, thank you very much.” Some Kurdish friends came over too and asked if they could help and we said, “No, you better throw away our phone number, you know, we’ll get out of this, but you could have problems.” So people were really courageous to offer us help at that time.

I was able to get through to my mother on the phone. I said, “You’ll hear things on the news and I’m fine and I’ll call you in a couple of days.” But then of course I didn’t ever call her again for 90 days until I was back in the US.

… Vic [Tomseth, consular office] called to say his friends at the British Embassy would come pick us up and we could stay in their residential compound. Two cars came late in the afternoon and picked us up and went to Bob’s house and took us all to Gholhak Gardens [a British diplomatic compound]. It felt good to be out of embassy housing since we worried the students would find the rental housing list and come looking for stray Americans.

But the next morning we got a call from Vic saying the British Embassy had been attacked the night before, and they felt they could not guarantee our safety, so we would have to leave.

That’s when Vic had the ingenious thought of calling his cook Sam from Thailand who was the cook for a number of American embassy employees. Because of this, he had keys to the houses. Not only could Sam help us hide, but he and Vic could speak Thai so no one listening would know about the plans or location. The Brits again gave us a ride, this time to the home of John Graves, who by that point was a hostage. Sam was there to greet us, and we slipped in trying to be as inconspicuous as possible.

“Within a short time, it was clear that holding the American hostages was earning support for the Khomeini regime, so he was not going to free them.”

The reality of the situation sinks in: Over the course of the next few days, we hid there, keeping out of sight with the lights off. The house was sparsely furnished, so we slept under rugs or in our clothes. Sam would shop and cook for us. He learned that the regular housekeeper, also Thai, was worried her boss would return and find his food eaten and wine drunk and be angry with her, so she wanted Sam to get us out. Without telling her where we were going, we snuck out and went to Kate Koob’s house. Vic Tomseth had told us that she had been taken hostage too. I remember it as creeping out in the wee hours through neighborhood backyards. But I am not sure if that is just a dream. In any case, we left more of our clothes in the washer. We didn’t have many in the first place since we weren’t planning on this being a long term event. By now we were down to almost no clothes and no money. So for those critical early days, thanks to Vic’s quick thinking, and Sam’s loyalty and courage, Sam could secretly help us hide. Within a short time, it was clear that holding the American hostages was earning support for the Khomeini regime, so he was not going to free them.

The secular government resigned and the Revolutionary Islamic Government took over . . . That is when Bob Anders called [the Consul General for the Canadian Embassy] and told him we were at the end of our rope.

… When he brought us over [to the Canadian ambassador’s residence], everybody thought this was short term, never imagining this could drag on for over a year. So [Canadian Ambassador Ken Taylor’s wife], Pat, had introduced us to the household staff as friends of Ken’s from Canada. There was the cook, and I don’t remember his name. But he was a member of the local Revolutionary Guard we found out later. And there was Guna Siland who I think was from India or some other South Asian country. So they were the domestic staff — the housekeeper and the cook. So it was kind of awkward after a while, because I thought, “Well, then we shouldn’t speak Farsi.” And then after a while we did.

I’m sure they were thinking, “Well, who — these are funny tourists. They come here and they hide upstairs when somebody comes to visit. And they don’t have any clothes and they never go out.”

So it was never really clarified, you know, just what we were doing there. Nobody ever spelled it out. Probably for their safety so they could always deny they knew who we really were

“There was a routine, and I think that’s what keeps you sane too, having a routine.”

Learning to Live in Hiding: There was a routine, and I think that’s what keeps you sane too, having a routine. Every morning we’d get up, go downstairs have breakfast. The Ambassador and Pat would already be gone. And at about noon, the staff would have lunch for us. And then we would read – I would read novels. Joe would read the Farsi language newspaper, friendly embassies and other Canadians were loaning us whatever books they had. And so I read every John le Carré [novel] they had. I think I’d already read Kurt Vonnegut, which was very appropriate. It was.

Then there would be news on late in the afternoon, and we would watch with talk about negotiations for the hostage’s release. We’d be very hopeful, and then they would fall through. And then they would start up again with another leader… and then that would fall through.

So there wasn’t very much good news. And then at one point, maybe it was Thanksgiving. [Pat and Ambassador Taylor’s] son, Douglas, came home. He was in his early teens and he came home from boarding school and he was there in the house for a while. So we played Monopoly with the OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) countries. And there were these gold playing pieces. It was a gift to Ambassador Taylor. So we played, you know, whatever games — Douglas wanted to play. And then we joked and said, “See you at Christmas,” and then there we were at Christmas. Wasn’t so funny then. But he never told anyone, you know, he never told anyone back in his school that he was going home and these people were hiding in his home.

“For my disguise I just took all the long hair and put it up, and they gave me fake glasses. I still have them.”

The Daring Escape: We knew something was changing because the Canadians started leaving. But, before that happened, they had started bringing people in and out, randomly. The Canadian Royal Mounted Police–their equivalent of the Marines–would start coming through so that the airport immigration people would get used to seeing Canadians coming and going. And they would also observe everything about how the airport worked. And they also were thinking about the best time for us to leave. So that’s why we left so early in the morning, because they thought well, you know, it’s the end of the shift, people are tired, they’re not going to worry about yellow and white pieces of paper matching or things like that. And there were not that many Revolutionary Guards around that time of the day…

[CIA Officer] Tony Mendez, alias Kevin Harkin, came to give us a choice of which of these three scenarios we were going to leave with. And so we had: going out as nutritionists, something we knew nothing about; oil company people,even less; or going out with this movie production company, which had all the props – concrete things that made it believable. Business cards, the magazine with an advertisement for our movie site search – and of course I felt comfortable with the movie production company, because I was the graphic artist. If somebody asked me to draw something, I could draw it. And Cora [Lijek] was the writer, the screenwriter, I think. Joe was a producer. He looks good in a turtleneck, so that was the logical choice. And you know, somebody asked Mark Lijek the other day if we trusted them. And he said, “You know, it’s not like we had a choice, send in another exfiltration team please.”

Q: And did you actually memorize a script?

There was not that much to memorize, what our names were and where we were born and how to say this and that in Canadian accent and things of that nature. We knew so little about Canada. We tossed everything we had from the USA, everything we owned that had any sort of American brand on it. And all the people from the Canadian Embassy gave us their clothes. And I had this suitcase full of sandals in wintertime in the snow. They gave me some more clothes to put in my suitcase. For my disguise I just took all the long hair and put it up, and they gave me fake glasses. I still have them.

So all I had to do was pull my hair back and put on some glasses because people only recognize me because of my hair and my height. So I didn’t feel very recognizable. I think Cora was probably the most uncomfortable being Asian American. It was harder for her to disguise herself and still look like her passport picture. Everybody was concerned that since we had interviewed so many people on the visa line somebody might recognize us. Luckily no one was really looking for us anyway, and it had been three months since the takeover…

And the other thing that happened that we didn’t know about until we read the books was the dates were wrong in our visas…

The dates, the entry dates for us entering Iran were wrong. The CIA had not used the new Iranian calendar. They had used the previous one from the days of the Shah. So if we had been caught with those, we would have been in big trouble. But Roger Lucy, the young Canadian officer, saw them. We did not see any of these items until those last two days. I don’t know if we would have caught the errors or not. Joe probably would have with his attention to detail. We might have been so happy to have our, our getaway stuff that we wouldn’t have even checked. Tony requested another set of passports and being a master forger he “corrected” the dates using Ambassador Taylor’s good scotch to moisten his ink pad. In fact that is the moment the CIA chose to memorialize Tony’s incredible contribution to the CIA. There is an oil painting in the CIA visitor’s center showing him sitting at the table correcting the dates…

[And then we just left through the airport.] For a moment they stopped Lee Schatz and asked why his mustache didn’t match his photo and he made some gesture so they let him through and then we did line up to board the flight and were told there would be a delay. That was worrying and we hoped it had nothing to do with us, and we didn’t want to still be hanging around in the airport with the Revolutionary Guard shift came in. Tony said to sit tight, he went to check I think with our New Zealander contact and found that it would be a minor delay so we figured it would look suspicious to try to change flights and send our luggage one way and us another, so we waited and finally boarded the plane.

“The sad part for the other families was that no one knew who had escaped. They all hoped it was their hostage who was free. It had to be such a letdown for them.”

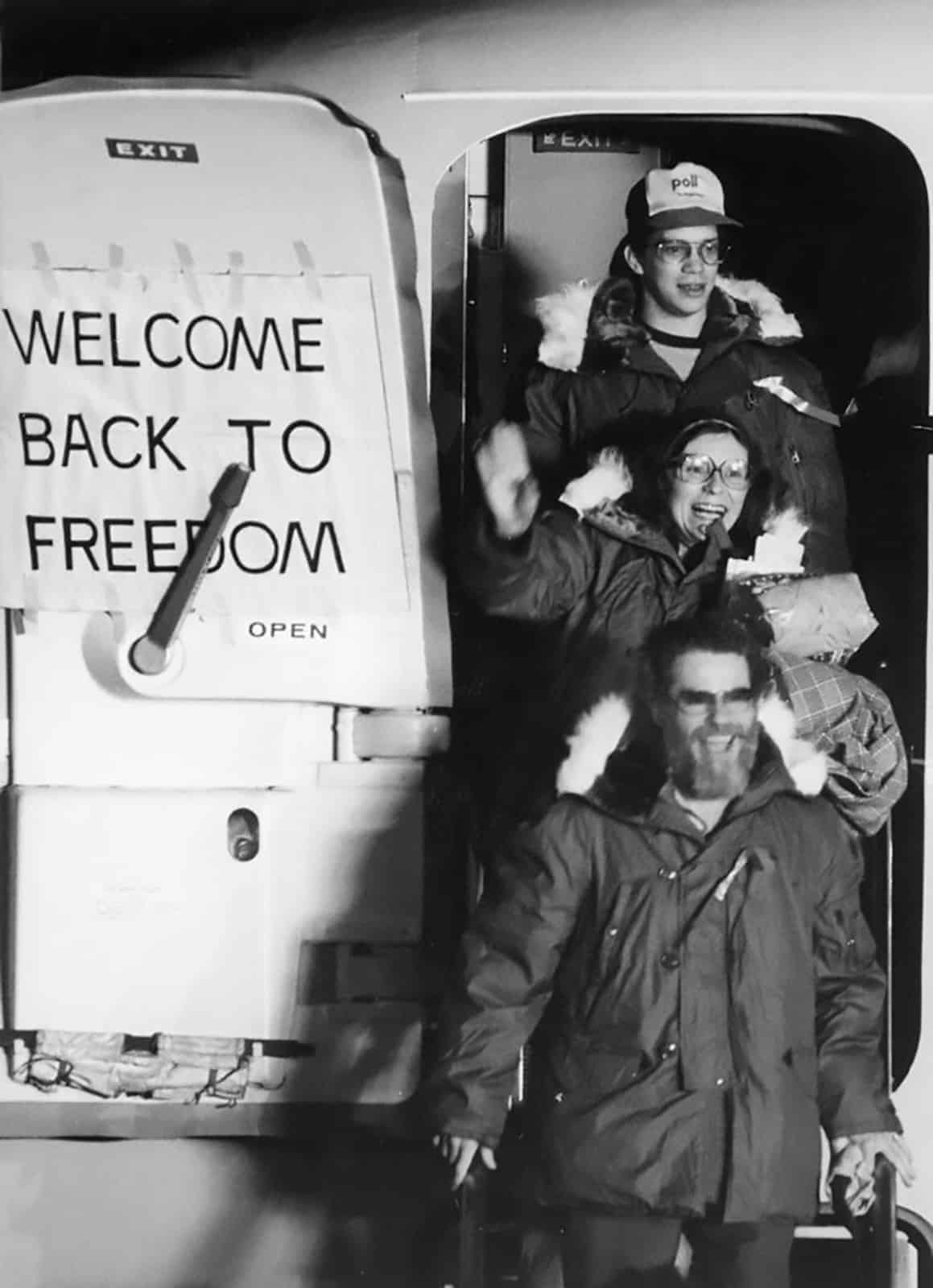

Finally Free: We arrived in Switzerland and traded in our Canadian passports for our very own U.S. diplomatic passports, and went to stay in the American Ambassador’s residence. It was beautiful and felt so very great to be out and safe from harm. The next day, as promised, [Canadian politician] Jean Pelletier broke the story as soon as Ambassador Taylor… got to Paris. The State Department had planned to have us hide in Florida until the hostage crisis ended, never dreaming it would be another year of course before they could obtain the release of the others. But then the secret was out. We had to go undercover again, trying not to antagonize the Iranians and have a chance somewhere to collect our thoughts so we headed to Rhein, in Germany. I remember it being dark in our little van, as we were driving on the highway with the radio on, they said the escaped hostages are just crossing into Germany, as if the press had a GPS system on the car or something. We were left with our mouths open!

The sad part for the other families was that no one knew who had escaped. They all hoped it was their hostage who was free. It had to be such a letdown for them. We were driving to Germany to go to the Rhein–the Main American Air Base–where we stayed a couple of days. The Base graciously opened the commissary for us, Sheldon gave us some wardrobe money and I bought the only dress in my size with matching shoes. Thank heavens! My own clothes. Then we flew back to the States to Dover Air Base in Delaware in the official plane of the Commander of US Air Forces Europe. End of tour.

“No one was really allowed to visit [the hostages]. They never had any news. They thought they were forgotten.”

Recovery and Meeting the Other Hostages: We did not know what conditions the real hostages were being subjected to so we thought they were just tied up. It was far worse than that. We would have been far more fearful I think so it was good we didn’t know what they were enduring…

I was an avid painter, but I couldn’t paint for a year after I got out. And it didn’t occur to me until maybe about 10 years ago that that must have been survivor guilt. Everything I’d paint, I’d ruin. And so then I would have these dreams that we were on that same plane as when we were leaving. And the other hostages would be on the plane, but they wouldn’t talk to me. So when they were released… [it was] important for us to be able to see the other hostages. And so [the State Department] brought us back from Palermo, Italy so that we could be there and see the others and have them tell us, “We were happy you got out.” Since everything they received was censored, they never had access to the Red Cross or anything. No one was really allowed to visit them. They never had any news. They thought they were forgotten.

[There] was a baseball game between the New York Yankees and the Montreal Blue Birds, something like that. The baseball team. And so that was in Sports Illustrated. And it showed our picture and it said — “These were the people who escaped with the Canadians and we’d said, ‘Don’t forget the other hostages’ — and things like that. And Reggie Jackson gave me his hat. So the militants had not censored that, because they weren’t thinking it would be in a sports magazine. So [the hostages] told us later that they saw that magazine and passed it all around to everybody to see it.

… They told us later it was like they were really happy someone had scored a point for our side. It made all the difference to us to hear it from them.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Early Life and Education

University of Tennessee Knoxville 1970-1973

University of Alabama 1974

Spouse Entered the Foreign Service 1978

Tehran, Iran—Worked in Consular Section 1979

Palermo, Italy—Worked in Consular Section 1980-1982

Tunis, Tunisia—Consular Officer 1982-1983

Marymount University, MA in Education 1990

Nouakchott, Mauritania—Spouse 1993-1996

Abidjan, Ivory Coast—Spouse 2001-2004

Khartoum, Sudan—Spouse 2012-2014