Shawn Dorman watched as Jakarta descended into violent chaos and destruction overtook the city. At the conclusion of the May 1998 riots, thousands had been burned or beaten to death, over a hundred ethnically Chinese women had been raped, and a large part of the city had been destroyed. Dorman’s family and all non-essential U.S. personnel were evacuated. As the unrest continued, Dorman met with students as they occupied the parliament building in a series of protests that brought about the resignation of then-President Suharto.

The people of Indonesia had been suffering from the Asian Financial Crisis. Suharto’s regime “The New Order,” which had remained strong for 30 years, was severely damaged by rampant corruption and its inability to maintain economic stability. Nationwide student demonstrations in support of democracy called “Reformasi” (reform) spread rapidly. On May 12, the death of four protesters at Trisakti University provoked mass rioting and looting targeted at ethnically Chinese individuals and businesses. Allegedly instigated by the Indonesian military, this violence was largely separate from the student movement that resulted in Suharto’s resignation a week later. The Indonesian Revolution was a success, but Suharto’s successor Vice President B.J. Habibie was not the reformer the protesters had wished for and violence against the Chinese left a lasting legacy of pain.

Shawn Dorman entered the Foreign Service in 1993. Her first assignment placed her in Kyrgyzstan, where she worked to establish the new embassy. Dorman served in Indonesia from 1996 to 1998, and thereafter worked as watch officer in Washington D.C. She retired in 2000, and is now editor in Chief at Foreign Service Journal and AFSA Publications Director.

Shawn Dorman was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy beginning on July 10, 2006.

Read Shawn Dorman’s full oral history HERE or for more Moments on Indonesia, click HERE.

Drafted by Wendy Erickson

Excerpts:

“They wanted the American government to know what they were up to and what they were thinking.”

Students Protest Against KKN : This was the Suharto era. He’d been in power for 30 years. We didn’t know what was going to happen, but it felt like it could be getting close to the end of that era. . . . [F]rom late 1996, it seemed that the students were starting to get politically active.

. . . . Indonesia had numerous legal youth and student “mass organizations”. . . . They’d issue statements and they’d hold meetings and conferences and they would talk about and call for political reform, openly. That’s what they were pushing for. And they were protesting against “KKN”— corruption, collusion and nepotism. . . . By the spring 1998, you could get t-shirts that said things like “No Suharto, No Habibi, No KKN.” I also was given a good one that had a picture of a military guy with a big gun pointing at a group of students, and in big letters “Let’s talk” (in Bahasa). It was out there. People were talking, and the students were protesting in larger and larger numbers on and off campuses around the country.

. . . . I’d meet with leaders of these groups and hear about their aspirations and concerns. . . . I would go out and meet people in cafés and have coffee and just listen to them. They wanted these meetings. They wanted the American government to know what they were up to and what they were thinking. . . . I was just getting to know the group leaders to try to understand them. I always found that I could get away with a lot because I looked very young, I’m small, and looked kind of like a student myself. I was the junior officer in the section, and the only woman. Many of my issues to cover were considered the “soft” ones, like youth and women. What could ever happen there?

“. . . I don’t think anyone was looking for trouble or for things to fall apart.”

Interrogations and U.S. Involvement: What happened later as the political situation heated up, into 1998, was that some of the people I was meeting with started to tell me that they were being watched and that they were feeling like it was more dangerous. . . .The Kopassus (Special Forces) had a special group, Team 6 or something like that, that was involved in “disappearing” student activists. That was a term that was used a lot. . . . Most of those activists who disappeared in Jakarta were later released following interrogation, I think.

. . . . What struck me, I have to say, when I got to Indonesia, was finding how close the U.S. government, and our military especially, was with the Suharto regime and the Indonesian military. That had kind of been how it was for a long time. Stability was good, the economy there had been doing well, there were U.S. business interests; that was the way people approached it, and I don’t think anyone was looking for trouble or for things to fall apart.

I came in not knowing that much about Indonesia, and was really surprised by the relationship. . . . . I couldn’t understand why we were so friendly with the Indonesian military when I kept hearing about cases of human rights abuses perpetrated by the Indonesian military. . . . Maybe because of traveling and spending time with young people, but it seemed obvious that the population wanted change.

“May 12 was the spark that led to the end of the Suharto regime.”

The Fall of Suharto: By early May, student demonstrations were going on around Jakarta and around the country pretty much every day. Student protesters were calling for democracy, reform and for Suharto to step down.

May 12 was the spark that led to the end of the Suharto regime. That day, four students were shot and killed at Trisakti University following a large demonstration and stand-off with the police/military there. Two other students were also shot but survived. Others were wounded. A large number of students were trying to take the demonstration off campus and got stopped in the road. That’s where the standoff went on for several hours.

Trisakti had been known as a university for reasonably well-off kids of politicians and civil service people, not a center for student protest and activism. I had gone over to Trisakti that morning (unless it was the day before, I can’t recall exactly) and witnessed a peaceful demonstration there. They had speakers addressing the crowd and it was a big but not chaotic event. As word that students had been shot spread, anger mounted. We were hearing that it was military snipers who shot the students, but the situation was not clear.

“It felt like Jakarta was on fire.”

Riots and Chaos: It was the next day that riots got started, and instead of students protesting peacefully on campuses, crowds took to the streets. I say got started because I would hear later, as did my colleagues in POL, that the riots may have been instigated by forces in the military, that it was not purely spontaneous. And it wasn’t the students doing the rioting. It felt like Jakarta was on fire. From the embassy, we could see smoke plumes going up in different parts of the city.

As we learned later, it was the ethnic Chinese who became the primary victims of the day of rioting. Chinatown was wrecked—fires, looting, businesses destroyed. We would hear later reports that ethnic Chinese women had been raped. Terrible things happened on that day. In one shopping center being looted, many were trapped inside and died in a fire there.

“The road to home to my 2-year-old, was blocked by fires and disturbances. [T]hat was one time I was afraid, not being able to reach my child.”

Confronting the Military: I remember late morning the day of the riots (May 14) going out with a Canadian diplomat colleague, a woman, and a driver from her embassy, to see if we could get a sense of what was happening. That was scary, and we could feel the chaos in the city. We would come upon crowds, saw burning tires in streets. At one point we were on a bridge and got out of the car to see what a nearby small crowd was doing. All of the sudden, a military formation appeared on the bridge.

There was a moment of wondering, do we run and take cover? Instead we approached the military, said we were diplomats from the American and Canadian embassies, and they let us pass. I made it back to the embassy, where I stayed until about midnight. The road to home, to my 2-year-old was blocked by fires and disturbances, and that was one time I was afraid, not being able to reach my child.

. . . . That day is what triggered the evacuation. . . . [The Emergency Action Committee] met that next morning and decided the embassy would go on ordered departure, meaning the evacuation of all non-essential Americans from the embassy and consulate in Surabaya, for what I think was that night.

“There were tanks on the streets, there were blockades up everywhere. We had to go through all these checkpoints and the city was just dead.”

City on Lockdown: The situation remained tense, and I was relieved to have my family out of there. . . . When we tried to get to the embassy the next day, we found the city was in lockdown. Basically. There were tanks on the streets, there were blockades up everywhere. We had to go through all these checkpoints, and the city was just dead. I mean, there were no people out. Amien Rais had called for the people to hold a mass protest march to the presidential palace and the military was trying to prevent that from happening. Everyone was worried about what would happen if it went ahead. In the end, Rais seemed to recognize the danger and called it off.

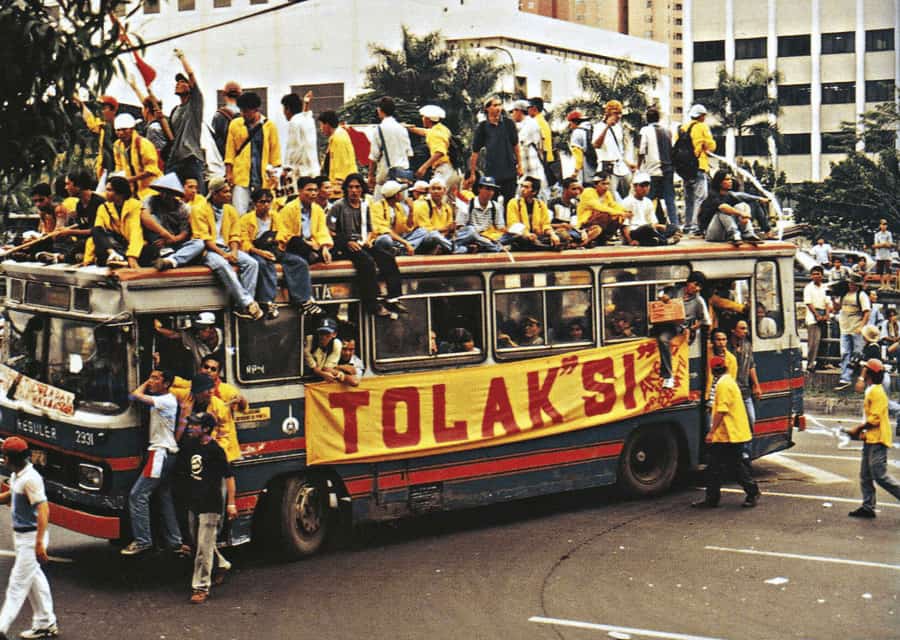

Instead students had begun to head to the DPR, the parliament compound. They started to arrive in buses to this huge fenced-in compound that was an area not in central Jakarta. The students were permitted to enter by the hundreds. And over a couple days some thousands of students wearing their different colored university jackets converged on parliament and essentially they set up camp there. That went on for a couple days with more and more students arriving by bus.

I went over there two or three times. The few of us left in the political section would go and check in and see what was going on there. And other embassies were sending people in and I was getting calls a lot from people inside. There were times when it got very tense, when you’d hear that there were instigators coming in to try to make trouble. And there were rumors that the military was going to come and start shooting; it was a very contained area, surrounded by high metal fencing. . . . And the military was massing outside the fence; they were there with their guns but keeping on the outside.

“I went over and it was just like a big party.”

Suharto Resigns: And then it was the morning of May 21 when Suharto announced he was stepping down. That evening there was this big celebration at the DPR compound. I went over and it was just like a big party. I remember seeing groups of military guys, inside the compound now, celebrating, dancing. It was a very festive atmosphere. But Suharto immediately named B.J. Habibie, his vice president, to be the new president. The students were looking for regime change and the vice president was not what they were hoping for, so it sort of took the wind out of the sails of this great excitement. He was seen as, well, he was Suharto’s guy. But he was talking about bringing democracy, and did start to take actions in that direction pretty quickly. That was the resolution.

. . . . I don’t think things get any better for a political officer than that time in Jakarta, being able to witness history from the front lines, to see the fall of a repressive regime and the beginning of a new road to democracy that the people—and especially the students—were demanding. It was inspiring.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in Government and Soviet Studies, Cornell University 1983–1987

MA in Russian Studies, Georgetown University 1990–1992

Joined the Foreign Service 1993

Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan—General Services Officer / Consular Officer 1993–1996

Jakarta, Indonesia—Political Officer 1996–1998

Washington D.C.—Watch Officer at the State Department Operations Center 1998–2000

Retirement 2000