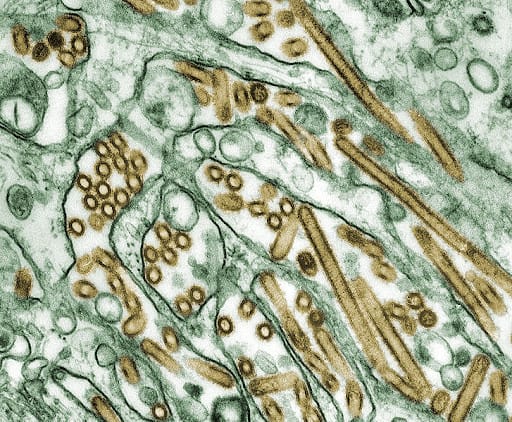

Several devastating pandemics have plagued human civilization throughout history. From the Black Death (1350) to the deadly Coronavirus, each outbreak has its own unique challenges and many human casualties. This was true for the virus that “shook” the beginning of the twenty-first century: the Avian Influenza.

Nicknamed the Bird Flu, the Avian Influenza had its beginnings in China (1997), but reappeared in 2003. The Bird Flu was evaluated as a potential pandemic, and continued to be a concern well into the 2010s due to its high mortality rate in humans. While the Avian Influenza can be contracted through contact with infected poultry, there have been instances where this pathogen has passed from human to human. Many health officials therefore feared that a mutated virus could easily transfer from human to human, thus potentially increasing the casualty count dramatically. Although there are still reports of poultry infected with the Avian Influenza—even in 2020—the threat of a widespread outbreak has subsided, thanks to international cooperation.

Despite the increased risk of infections spreading from country to country due to frequent travel, the international community has established serious measures to curb the spread of deadly viruses. In response to the Avian Influenza, affected countries used techniques—quarantines, vaccinating at-risk animals, treating infected individuals, and launching information campaigns—to contain the Bird Flu, prevent further spread, and keep media-induced anxiety at bay. While certain countries had more success than others at curbing infections, it is clear that the international community as a whole engaged in a highly collaborative campaign that prevented further Bird Flu casualties.

Retired Foreign Service Officer Margaret Jones worked with the Avian Influenza Action group in 2006. She saw first-hand that while the international community has cooperated many times when faced with an international health crisis, roadblocks and difficulties do exist. Those working to contain the Avian Influenza in Indonesia came face-to-face with a particular difficulty during the outbreak in the early 2000s. Jones discusses her experience negotiating with the Indonesian government to release Avian Influenza virus samples to the World Health Trade Organization network in hopes of streamlining vaccine production.

Margaret Carnwath Jones’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on July 22, 2010.

Read Margaret Carnwath Jones’s full oral history HERE.

Drafted by Elizaveta Pinigina

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“They just were demanding things we couldn’t do.”

The Avian Influenza in Indonesia: In ’06 I started working with the Avian Influenza Action Group which Ambassador John Lange headed. We had funding and the issues were fascinating. President Bush took the lead in pushing action. Some people feel looking back that the effort that went into avian influenza may have been a reaction to [Hurricane] Katrina and the perceived inaction there. If the new avian influenza, which is fairly lethal in the humans that catch it, mutated to be easily transmissible and caused a pandemic similar to the Spanish influenza of ‘18 people might say you didn’t do enough preparation on that either.

I was brought in to work with the international organizations, especially the World Health Organization, WHO. The first year I wasn’t full time but the Indonesians sparked negotiations that turned it into a full time job for years. Indonesia was one of the epicenters for the human cases that were found. Like the ‘18 Spanish influenza, it affected mostly young people and young adults, turning on their immune system which in a way kills them in reaction to the influenza. Older people and young people don’t have as active an immune system, and were not as affected. The cases were limited, but the kill rate was high, which was one reason this new influenza virus sparked such interest. The fear was that it would mutate so as to be easily transmitted from human being to human being.

“ Indonesia’s very difficult health minister decided that it was unfair to share their virus samples when vaccine companies would make money . . . .”

. . . and the supply of vaccines for Indonesia would be limited. So Indonesia stopped sending virus samples to the World Health Organization network that developed after WWII to analyze virus samples. The samples go to labs in developed countries like the U.S. CDC or Centers for Disease Control. There is one in Italy, and there is a network for animals as well. Those experts study what is happening and then they make recommendations on what should be in the yearly influenza vaccines that come up. And the prevalence of influenza in certain regions may differ so the recommended vaccines will also differ. Manufacturing influenza vaccines is still based on using eggs and there is a large lead time between starting the process and producing the vaccines. Thus there is also a large lead time between when a pandemic starts and the when the relevant vaccine is available. Supplies are limited and generally developed countries have signed up with manufacturers leaving less developed countries at a disadvantage in getting the vaccine. So this is a hole in the system. Indonesia and other developing countries were concerned they wouldn’t have access to vaccines if there were a pandemic. Indonesia was also concerned about the entire vaccine system and used its samples as leverage. As a result very complicated negotiations started on sample sharing.

“Influenza vaccines are covered by a lot of the rules that cover weapons of mass destruction.”

The Negotiations Begin: In one sense the Indonesians seemed to want to be paid for the samples. The issues were tangled, but one was that if you weren’t providing samples you were impeding the study of the virus as it evolves and couldn’t also impede development of a vaccine if it becomes very infectious. We were also looking at ways we could get vaccines to developing countries because there was a basis to their concerns. Lots of countries don’t use the normal yearly influenza vaccines. So we had negotiations started. They can get very convoluted.

So for example, if you were sending an influenza vaccine to Cuba you had to get all sorts of special permissions in case they would back engineer it into a weapon of mass destruction or a biological agent. You can’t waive these rules. Avian influenza was covered so when the Indonesians asked for the return of a sample the CDC ran into these rules. The original samples are highly pathogenic and must be handled in labs with sufficient bio security. When you are talking about the vaccine, they engineer the viruses from those samples so that what goes to the drug companies and the vaccine is not the highly pathogenic virus but a low path form. You had to certify that the vaccine was going back to a lab in Indonesia with a sufficient bio security to handle it, and then you had to do the export license. You could see how hard it was to explain to the Indonesians why the response to their request for the samples back was not immediate. People would say can we waive this? I would say, “You are in an area where there are no waivers. You do the procedures or you don’t do the procedures. This is national security you are talking about. No there isn’t a waiver.” So it is interesting how many seemingly simple issues become complex. And this specific example surely contributed to Indonesian distrust.

I have to go online and see how the negotiations were concluded. They just were demanding things we couldn’t do. Then some tried to relate it to the Convention on Biological Diversity. Under the Convention people own resources from their country, and they want to make sure that drug companies don’t come in and use a resource from their country without compensation. We were arguing that we really didn’t think those rules applied to something like an avian influenza. Under biological diversity one of the goals is to maintain the diversity of sources in the world in case they become useful in the future. But the goal with an influenza virus is not to maintain it. You want to kill it to get rid of it. Though as a footnote, smallpox has been eradicated but the U.S. and Russia still have smallpox samples in their labs. Each time the question of destroying those stocks comes up in WHO it is deferred. I don’t think they will ever give them up.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA, Duke University 1966

MA, SAIS, Johns Hopkins University 1968

Joined the Foreign Service 1975

New York—U.S. Mission to the UN, Committee on Human Rights and Social Issues, Executive Officer 1983-1985

Washington, DC— Bureau of International Organizations 1998-2001

Post Foreign Service Career

Avian Influenza Action Group 2006-2010