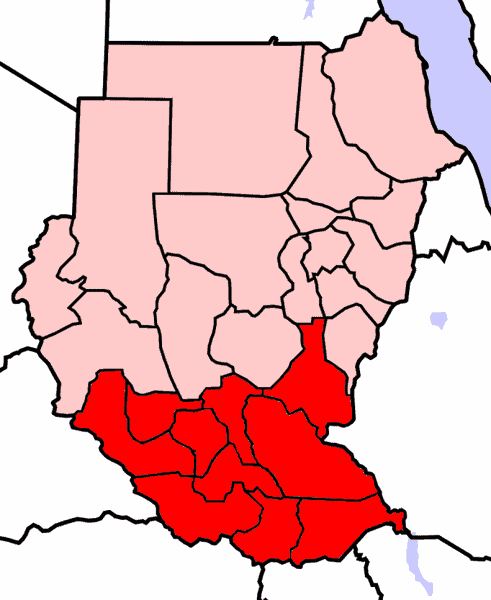

Creating a country ex nihilo is never an easy feat. How does one construct functional government institutions from scratch in a land that has been in conflict for decades? Ethnic tensions and former colonial administrations make this uphill battle even steeper. South Sudan faced this very situation

after signing the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA). Through the CPA, the governing National Congress Party of the North made peace with the South, which was controlled by the Sudan People’s Liberation Army/Movement (SPLA/M) led by John Garang.

The conflict had been sparked by the Arab dominated North imposing direct control and Sharia law over the predominantly Christian and traditional South. Southern leaders created the SPLA/M and rose up in revolt to fight for Southern autonomy. By 2004, twenty-one years of continuous armed conflict led to widespread destruction, the deaths of millions, and the displacement of millions more. The 2005 CPA established power sharing between North and South, created an autonomous regional government, and established a six-year transition period during which a referendum on independence would be held. This meant a government would have to be created—including new ministries and government institutions built from the ground up—and governance would have to be established.

Gerald Hyman served as a USAID officer in South Sudan both pre and post-CPA, and he experienced first-hand the complex politics surrounding the conflict and peace as he worked with the SPLA/M. During the latter part of his tour in the fledgling country, he evaluated the proto-ministries being created. Given his background in the country, what he found made him less than optimistic about the success of an independant South Sudan.

Today, the country is being ripped apart by yet another civil war caused by ethnic tension, poor governance, and political power struggles.The following excerpts are Gerald Hyman’s reflections on the conditions post-CPA that ultimately contributed to South Sudan’s downturn.

Gerald Hyman’s interview was conducted by Ann Van Dusen on November 16th, 2016.

Read Gerald Hyman’s full interview HERE.

Drafted by Merrill Rabinovsky

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“I know there obviously were frictions because they appeared ominously afterwards. But they weren’t obvious unless you knew these people a lot better than I did.”

HYMAN: Anyway, so I went back to South Sudan again, more than once, but the second particularly memorable time was after the CPA, the Comprehensive Peace Agreement had been signed.

Q: And date?

HYMAN: You know, 2005 I think.

Q: Yes, maybe.

HYMAN: And so we went again to Garang’s camp and all of the commanders were there and most of the people that Garang wanted to have his inner circle and part of his new government. And he didn’t get to the camp until a few days after we were already there. He was going around to try to sell the CPA and he did the same thing after we were there and it was on one of those trips that his helicopter went down.

Q: So, why did he feel he had to sell it if everybody was already in favor of it?

HYMAN: What he felt he had to sell was the compromises he had made. So, for example there was a five-year transition period; what was going to happen during that time, etcetera, etcetera.

So, you know, all of us sat around with him and sat around with each other and our job was to try to put together the proto ministries. So, that’s kind of heady stuff, sitting around and talking about the justice ministry or the whatever ministry.

Q: Did he have strong ideas about which

HYMAN: He didn’t participate. These were recommendations that were made by working groups to him but they were made by people he trusted to be the next education minister or the next justice minister or the next whatever. It became quite autonomous at first and then it became a separate independent state after the referendum. I know there obviously were frictions because they appeared ominously afterwards. But they weren’t obvious unless you knew these people a lot better than I did. On the face of it it was a pretty congenial session. And then there was a meeting with Garang and various different people presented these different proposals to him and so on and etcetera. And we left and went home. But then I went back several times during the transition period for a variety of assessments, this and that. And then after independence. So, the last time I was there, I’d have to look it up on my screen, I think it was two summers ago. It was in the summer, and was to review what was going to happen to the democracy strategy and particularly to pay attention to the potential for conflict or to actual conflict by that time but not just that. And so I did finish a report and left. And then it was, I don’t know, three, four or five months after that when the thing just blew up. But the potential for that was there. And I had started an article which I never finished, should have called ‘The Uncertain Future of Democracy in South Sudan,’ in which I talked about some of the groups that are in South Sudan and their historical animosities with one another, in particular the Nuer and the Dinka. So, in anthropological literature this is classic; there was a classic study of the Nuer and the Dinka. One guy did the Nuer, another guy did the Dinka so these were very, very well known cases in anthropology. So, there were a half a dozen really central cases that set the tone for anthropology as an empirical matter as opposed to thinking about symbolic stuff. And a couple of cases were the Nuer and the Dinka. There was another one on the Trobriand Islands, which is in the Andaman Sea by Malinowski. So, I knew the Dinka and the Nuer through books. No one had to tell me how they were organized; I already knew that.

Q: Or their hostility to one another.

HYMAN: Oh yes. Now, their hostility to one another goes way back but it was a more ritual hostility, number one, and number two was fought to the extent there were actual battles with primitive spears, not Kalashnikovs. So, at first there were raids mostly by one against the other for cattle and for women. So, you would capture a woman and you would make her your wife. You didn’t eat her, you didn’t rape her; you married her. So, that had been there for quite a long time and the number of casualties was low. It was mostly raiding. And not only that but these raids went below the Nuer Dinka level so they were segmentary. The groups within the Dinka that raided one another and so on below that and below that and below that. So, the Dinka Nuer conflicts were just one element of this raiding that took place all the way down both sides. But now it became less but not entirely less of one Dinka group against another Dinka group but rather the Dinka against the Nuer and now with real weapons and substantial deaths. And that took place during the war, including by Garang against the Nuer, Machar’s group, and vice versa.

“…when there’s resources at stake, commitments to integrity don’t always last.”

Q: So, I was going to say do you think Garang could have kept it together?-

HYMAN: I think he might have been able to. I don’t know. I was always unsure. You know, he talked the right language for sure, definitely. And all the people around him, no matter what their group, parroted that language. Once the thing had become a country and the oil began producing and real stakes were at hand, would he have been able to keep a lid on it. I don’t know. I’m not so sure. His charisma was substantial but would it have bridged these, not just the ancient and well established conflict relationships. There were more ritual and raiding than real conflict in the war sense but there were also personal ambitions. There are allocations of ministries at stake and then there was the oil.

Q: Yes.

HYMAN: So, would he have been able to keep control of the corruption, of the nepotism, of the greed? I don’t know. He claimed he did. He knew it was going to be a problem. He had a guy who was sort of a father of anticorruption writing, a guy by the name of Klitgaard, come and address all these people while he was still alive about the potential for corruption and of course they all said they weren’t going to do it. But when there’s resources at stake, commitments to integrity don’t always last.

Q: So, would you say that early on, both because of the work you’d done in other conflict situations and because of your training as an anthropologist you had concerns about it sticking?

HYMAN: Yes. I would say that I didn’t have burning concerns but I kept saying to myself well, what happens if, I mean what if this doesn’t go in the great beneficial way that everybody says it’s going to go. Have we thought about that? And I went out during the CPA period and did an evaluation of the major proto ministries. There were only a couple of us on the team; I can’t remember how many there were, I’ll have to look, but a couple people were on it, and I took the major ones. So, I took the bank, the proto bank, I took the president’s personal office, yes. And I took the finance ministry. And I took, I think I took also the law ministry and the other guy got whatever else. And it was very clear that the reason they wanted an assessment was we were paying very large amounts of money to some very senior people to give advice to these ministries as to how to structure themselves. And so again, I used a more anthropological method and just sat down and talked with these guys, said what’s going on here and what are you doing and so on and so forth. So, one guy who was on loan from Justice or Commerce and he was a senior executive service guy. He was sitting out in Juba supposedly giving advice to the bank. I don’t know where he was from, which agency. And they wouldn’t tell him how much hard currency they had and he said well, I know you have hard currency, you’re hiding it, I understand that, but how much do you have and what are you going to do with it because that’s going to be the backbone of your new currency. They wouldn’t tell him.

Q: Did they not know?

HYMAN: Oh, they knew they just didn’t want to divulge it to him. So, what was he doing? The law guy, I think, I think it was even the banking guy, wound up teaching Excel 101 to some incoming uneducated staff as they were going to join this ministry because they wouldn’t let him in to any of these other things. So, I wrote all this up. And I said you’re paying $250K, $300,000 a year for these guys and they’re not doing what you’re thinking they’re doing.

Q: Because they can’t get access.

HYMAN: They can’t get access. They don’t want them here. They’re not going to tell you they don’t want them here but they’re going to marginalize them which is what they’re doing. I don’t know why AID doesn’t know about this and AID doesn’t do something about it, mainly sit down with these ministers and say either you want these people or you don’t but we’re not going to spend $500,000 with overhead and so on and so forth to keep these people here so they can teach Excel 101. We can send someone to teach 101 for a lot less than that. And these guys have jobs. So, this is not a good use of our resources. But they didn’t.

Q: They didn’t?

HYMAN: No, because I guess they didn’t want to rock the boat. So, this don’t rock the boat problem is a constant issue.

“…the readiness of these ministries to meet their functions was very clearly, to me, uncertain”

HYMAN: And not willing to face up to what’s going on right in front of your eyes. I mean you didn’t have to be a super anything, just ask these people, sit down and say what do you do all day. So, there was another team of two that was in the finance ministry. This guy was in the bank that I’m talking about; a couple in the finance ministry. The woman had managed to worm her way in, she was a South African, and she had managed to get herself inside. The other guy did not. And she had managed to do it by doing all kinds of work maybe. But as a whole they were not doing what they should have been doing.

Q: Right, right.

HYMAN: And so the readiness of these ministries to meet their functions was very clearly, to me, uncertain because that’s why these guys were supposed to be there in the first place.

Q: So, think about the budget. I’ve got some theories about why in the face of evidence that this was money very poorly spent, AID would continue to fund it. But at that point Congress had appropriated funding specifically for South Sudan. Is that correct?

HYMAN: Oh yes.

Q: And there were outside interest groups that were very strongly lobbying for a robust response. And I don’t know what the State Department role was but presumably they wanted this to happen too.

HYMAN: Sure.

Q: So, all of those things probably put pressure on AID to stay the course

HYMAN: Yes. And the mission director’s orders as far as he or she was concerned was to keep the ball rolling, do what you need to do to support the transition. That was the first, second, third, fourth and fifth objective. So, he or she would have had to take some heat to say

Q: We can’t spend this money well.

HYMAN: Yes. And this program that I’m talking about was not a tertiary program off in the boondocks someplace. This was the U.S. technical advisor to the central bank of South Sudan. Or the finance ministry of South Sudan or the president’s chief of staff. Those are the ones I touched. So, if they weren’t going to get the finance ministry right and they weren’t going to get the bank right, what was going to happen?

Q: Right.

HYMAN: And we did not go into the military.

Q: Yes. But there were separate channels.

HYMAN: Yes. There might have been but I don’t know about that. But we didn’t do it, AID didn’t do it and we didn’t meet with them.

Q: Right. What were you hearing from the Hill during all this? Just go, go, go?

HYMAN: Yes. I wasn’t hearing anything personally but that’s what

Q: You didn’t talk with staffers personally?

HYMAN: No, I wasn’t supposed to go talk to the staffers. Andrew was going to do that or possibly Roger.

Q: Okay. So, did you leave AID shortly after the Sudan situation?

HYMAN: No, I left, well, I left in 2007 at the very end of the year I got this opportunity as I mentioned to you to work on governance in this program at CSIS so I took it.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

University of Chicago—B.A., M.A., PhD in Anthropology

Doctoral Research in Malaysia—Economics, Religion, Politics, and the Rubber Market

University of Virginia—J.D.

Joined USAID 1989

Bureau for Europe and Eurasia 1990s

Senior Management at Office of Democracy and Governance 2000s

Director for Bureau for Democracy, Conflict, and Humanitarian Assistance 2000s

Left USAID 2007

Senior Advisor at the Center for Strategic and International Studies