The purview of an ambassador in a U.S. embassy extends beyond the geographical borders of their host nation and into the intricate global network shaped by the country’s history. In some countries, this may involve regional tensions and instabilities.In others, it may entail navigation of long-standing border disputes.

For others still, an ambassador takes on the relationship of a nation to its former colonies or current territories.

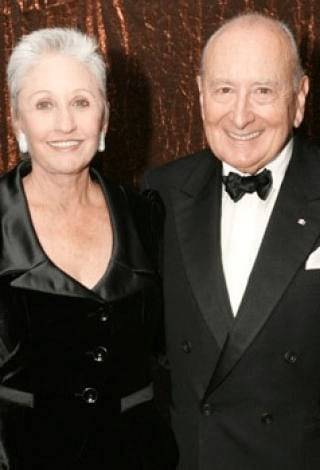

Ambassador Edward Elson arrived in Denmark in November of 1993 to embrace his long-standing interest in politics more fully—having already held roles in banking, civil rights, publishing, National Public Radio, retail, and education. However, this posting also meant embracing the relationship between the host country and its autonomous territory of Greenland. Greenland had formerly been a Danish colony, dating as far back as the 1700s. Greenland then became fully incorporated with the 1953 Danish constitution. Greenland now has limited autonomy and exists as part of the Kingdom of Denmark. As of June 2020, Greenland’s foreign relations largely operate out of Copenhagen, Denmark. However, on June 11, 2020, the U.S. announced plans to reopen its consulate in the Greenlandic capital of Nuuk, where it had not been present since 1953.

Elson found himself caught between Denmark and Greenland, as he represented U.S. interests at the Air Force Base in Thule, Greenland, much to the consternation of the Greenlandic prime minister. This tension only grew when the presence of atomic weapons on the base in the 1950s came to public light, in violation of the Danish constitution. For Elson, this revelation meant balancing the safety of a sensitive U.S. outpost, the Greenlandic desires for control of surrounding land, and Denmark’s own goals of deflecting a national scandal.

In this “Moment in U.S. Diplomatic History,” Ambassador Edward Elson discusses his dealings around the Thule Air Force Base, including his efforts to outsmart the press, coordinate with the Department of Defense, and maintain congenial relations with both the Danes and Greenlanders.

Ambassador Edward Elson’s interview was conducted by Chares Stuart Kennedy in 2012 and Mark Tauber in 2017.

Read Ambassador Elson’s full oral history HERE.

For more Moments on Ambassador Elson’s career, click HERE.

Drafted by Miranda Allegar

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“‘I think we can make a deal.’”

Opening Negotiations: I want to tell you about Thule Air Force Base and an extraordinary incident that occurred during my tenure. The United States has a significant multi-use facility created during the Second World War and used during the Cold War as a base for our SAC bombers. It’s still there and used for other purposes today. I used to have to go several times a year as part of my job to visit the base. The Ambassador always makes a visit. I had developed a friendship with the Greenlandic Prime Minister. Greenland is a self-ruled colony of Denmark.

The first time I met the Prime Minister of Greenland was in his office in Copenhagen. He was an Inuit, what we call an Eskimo, and he looked like a little Buddha. He spoke English, but poorly. I went to his office to discuss Thule with him. He opened a drawer – it was ten in the morning. He said to me, “Do you like cognac?” and I said “Yes,” and he opened a drawer and took out a bottle of cognac and two glasses, tumblers, and he asked, “Would you like some?” and I said, “Yes.” Of course, I thought that was what he wanted me to say. He fills up one glass for himself and fills a glass for me. So at ten in the morning we’re drinking cognac in the Inuit Prime Minister’s office and he starts telling me what he wants us to do at Thule.

I thought to myself, “How do I negotiate with a Prime Minister?” And then I thought. “Greenland has 57,000 people. I’m really talking to the Mayor of Augusta, Georgia.” So I said, “Mr. Prime Minister, what do you really want?” And he said, “You know what I want,” in a very thick, heavy accent. And I said, “Yes, I think you want to get re-elected.” He answered, “Yeah.” I said, “I think we can make a deal.” We had an excellent conversation. We left his office, and the press was outside with cameras. The first thing he says, “Best American ambassador ever, but…” and he goes into a diatribe, “He didn’t give me this; he didn’t give me that,” which were things about which we had never spoken. So I started laughing, and I turned to him and said, “Okay, you got me. But this is the only time you’ll ever have that opportunity because I learn very quickly.”

“‘It’s open space at the top of the world . . . . We can’t allow them to jeopardize the security of our base.’”

Scandal Strikes: The Danes found that in 1953, against the Danish constitution, the then government had allowed atomic weapons on their territory at the Thule Air Force base. It had been a secret from the public for over 50 years. The press learns about it during my watch, and it becomes a major issue, highly publicized and frightening to the government, who were accused of lying to the people for over 50 years, no matter who was Prime Minister. The government was threatened and feared it would fall. The press came to me and asked, “Do you know anything about this? Were there atomic weapons in Thule? Does the U.S. have them at their base?” . . . I said truthfully, “I’ll be very candid…” (and I did not know for sure, so I was telling the truth) “I know more about General Custer and Little Big Horn than I do about atomic weapons at Thule.”

Subsequently, the Secretary of Defense, Bill Perry . . . arrived in Denmark, and he asked, “What questions am I liable to be asked?” And I replied, “The big question they are going to ask you about is Thule Air Force Base and atomic weapons. You have to be very cautious because the Danes are deeply concerned about this.” . . . The press asked him the question, and he said, “I don’t know, but I will find out.” He found out that there were atomic weapons on Thule, and it almost caused the fall of the Danish government. Everyone was blaming the current government for continuing the cover-up, not that they allowed the weapons to be there (at this point there weren’t any), but for continuing the lie. They had a white paper done by a special commission, and it became a significant scandal in Denmark.

. . . Months later, I received a call that the Greenlandic government wanted the U.S. to return land that is outside of Thule Air Force Base, contiguous to it, that had been a burial ground for their ancestors, and we were leasing it for a thousand years, or whatever. The Danish government called me and said they wanted us to give it back to Greenland. And I said, “No.” They said, “Why not?” and I said, “The reason is the Greenlandic government could build an Iranian consulate there. They can do anything they want with it and they will do anything to make life difficult for the Danish government, and Thule Air Force Base has no defenses. It’s open space at the top of the world. There is no need for fences or guards or whatever. We can’t allow them to jeopardize the security of our base.” Well, the Danish relationship with Greenland is historically similar to the American relationship with the African-American community. The government was embarrassed by their treatment of the Greenlanders. They will do anything the Greenlanders ask. They have this great sense of guilt and also the Scandinavian standard of egalitarianism. They allow the Greenlanders to continually accuse them of mistreatment. Well, the Danes were really delighted that I said, “No,” They could say the Americans refused.

“‘Buddy, you want me to be the fall guy? You’re going to be the fall guy.’”

Blindsides: Subsequently, the Danish government, under great pressure from Greenland, instructed their ambassador in Washington to talk to the new Deputy Secretary, Tom Pickering, who knew the Danish ambassador from another post they both shared. Pickering says he will fulfill the request and he sends me a cable instructing me to accept the Greenlandic proposal. I had access to most everyone in the State Department hierarchy, and if I called directly, they would answer my calls. His predecessors, Deputy Secretaries of State, were all friends of mine. If I called, I would and get an immediate reception. I called Pickering twice; he didn’t answer either call. I called a third time; he still didn’t answer the call. On my fourth try, one of his assistants said, “Ambassador, he’s not going to answer your call. What he instructed you is what he wants.” I was disconcerted and discomfited by it all, so I decided to do it the State Department way. I sat down and wrote a cable saying, “I’m going to do what you instructed me to do; however, you should know the last time these issues came up, the Danish government almost fell by the Department’s response.” I explained exactly what had happened. “If you insist on reversing what I have said, you are going to run the risk of a terrible problem within Denmark itself, so it’s your call.” And he reversed his decision. What I suggested was, “Buddy, you want me to be the fall guy? You’re going to be the fall guy.” And that solved the problem. We did not give it back.

Now, at one point, the Danes tried to make a show for the Greenlanders that they were really trying and asked me for a meeting in Greenland with the Greenlandic government over this issue. I called Boulder, Colorado and asked particular SAC officers to fly from Boulder, all generals, and meet me in Greenland. We all arrived in Greenland, and as we arrived, and the Greenlandic Prime Minister was, at the same moment at the airport, leaving the country. He left the day we were coming because he did not want to be the cause of a continuing problem. Yet, he wanted to give the appearance that he was trying to get this land back for the Greenlanders. So he sent his housing minister to negotiate with us, which was ridiculous. The Danes sent two of their diplomats.

My staff had found where the Danish foreign ministry had once said that “the Americans are allies but not friends and we don’t have to do everything they ask.” I read that back to the Danes who were present, and they said, “Where did you get that?” and I replied, “From you.” At that moment, they announced to me, “Greenlandic Television is outside the meeting room. They want to interview you about this.” So I said, “Fine.” What they were doing was trying to force me to embarrass myself as opposed to the Danish government being embarrassed. I went outside the meeting room, and before me was a young woman reporter from Greenlandic Television. She asked me, “Why won’t the United States of America return this little piece of land to Greenland?” And I replied, “Well, who said we wouldn’t?” And she said, “What do you mean?” I said, “We will return it if the Danish government provides the security for the base.” She asked, “How much would that cost?” I said, “I don’t know, 30, 40, 50 million a year?” The Danish diplomats were watching, pulled me aside and said, “You blindsided us with that.” I said, “Now wait a minute; I didn’t ask for this interview. You set it up because you were blindsiding me. Now you have to explain it.” The Danish newspapers the next day headlined, “U.S. will return the land outside of Thule for $50 million a year,” and that ended the affair immediately, as the Danish government did not want that obligation.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in Political Science, University of Virginia 1952–1956

JD, Emory University ~1956–1959

Career highlights

President’s Commission on Obscenity 1966–1970

Chairman, Georgia Advisory Committee to U.S. Civil Rights Commission ~1974–1977

Chairman of National Public Radio 1977–1980

Rector of University of Virginia 1980s-early 1990s:

Appointed Ambassador to Denmark 1993

Copenhagen, Denmark—Ambassador 1993–1998