Being a U.S. soldier and fighting for your country overseas is an incredible sacrifice. The extended time away from family, necessity to quickly adapt to new environments, and the witnessing of the tragic repercussions of war are all difficulties that soldiers encounter.

While the government appreciates all of these men and women for their service, it honors a few particularly ambitious ones as “heroes of war” by awarding them medals for their courage on the battlefield.

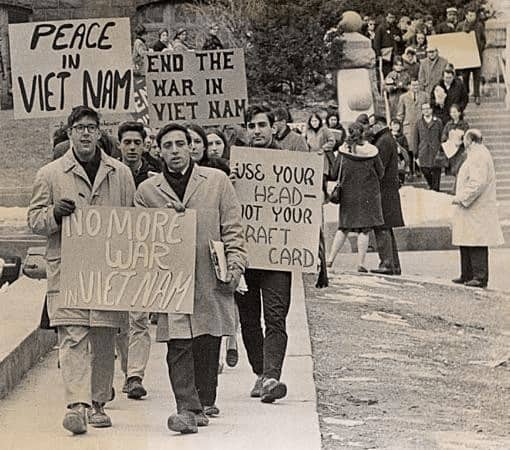

The Vietnam War pitted U.S. ally South Vietnam against communist North Vietnam, and occurred in the midst of the Cold War, when the world was divided into competing ideological camps. It was an extremely contentious issue in the United States, bitterly dividing the population. Many pegged the war to be “unwinnable,” and did not see value in sending their boys to fight in a faraway land. Furthermore, the photos and videos sent home from reporters in the field exposed Americans to the true horrors of war, especially its devastating effects on the civilian population.

Although he was not fighting alongside U.S. soldiers while serving in Vietnam during wartime, FSO Kenneth Quinn represented great bravery on behalf of the Foreign Serving. Quinn’s experience illustrates the obstacles that Foreign Service Officers can face while serving in war-stricken countries.

Quinn thought his days were numbered after the State Department informed him in 1968 that for his first assignment he was being sent to Vietnam, at the time known as a “diplomatic death sentence.” However, Quinn enjoyed his time in Vietnam and chose to remain there after his first assignment was completed. While in Vietnam, Quinn lived through many experiences, some even life-changing. This “moment” in U.S. diplomatic history discusses one of these instances—a time when he saved a young Vietnamese boy’s life.

Quinn went on to be the Ambassador to Cambodia from 1996 to 1999. He also served as the Deputy Assistant Secretary of State and as a member of the National Security Council at the White House.

Kenneth M. Quinn’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on August 8, 2013.

Read Quinn’s full oral history HERE.

Read about counterinsurgency and the Vietnam War HERE.

Read more about the “unwinnable” war HERE.

Drafted by Sophie May

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“He was desperate for someone to help him and had an anguished look on his face that was begging me for help.”

Fight or Flight: It was December, 1968, and I had only been in Vietnam a little over a month and was still assigned to the provincial advisory staff when I had my first direct encounter with a life and death situation. I was driving to the MACV [Military Assistance Command, Vietnam] provincial headquarters when the calm of a languid tropical afternoon was abruptly broken by a crowd of wildly gesturing people standing in the middle of the road. Since the Tet Offensive had only been only a few months earlier, my first reaction was one of apprehension: was this some type of Viet Cong trick that we had learned about in training to try to get me to stop? As I slowed my vehicle preparing to do a U turn and get away, I saw a young man emerge from the crowd carrying the limp body of a boy about 8 or 9 years old, whose eyes were shut and his stomach covered with blood. He was desperate for someone to help him and had an anguished look on his face that was begging me for help.

I reached over, opened the door, and pulled the seat forward and the young man climbed into the back seat of my Scout holding what turned out to be his younger brother. As I pulled the door shut, he told me in Vietnamese that there was a gun in the house, someone had been playing with it and his younger brother had been shot and now appeared dead.

I knew there was a military hospital at the 9th ARVN [Army of the Republic of Vietnam] Division headquarters, but it was on the other side of the city and across the river. With the horn blaring and the headlights flashing, I began driving wildly through the heart of this typical provincial town, made up of narrow streets clogged with pedicabs, motorbikes, and vendors. People shouted and gestured menacingly at me for being the rude American and disregarding their safety.

“ I drove out onto the bridge and at high speed raced toward the other end straight at the oncoming trucks.”

Fast and Furious: Once I was through the market area, the biggest impediment of all remained. It was the one-lane bridge that crossed the Sa Dec canal, which had a person sitting in a tower in the middle controlling traffic with a stop and-go sign. The hospital was on the other side and there was no other way across.

As I roared up the ramp, cutting off other civilian vehicles to go on to the bridge, the sign turned from green to red for stop. I could see at the other end a convoy of huge Vietnamese military trucks beginning to pull onto the bridge. The military always took precedence over civilian traffic, and such convoys would sometimes take 15 or 30 minutes or more to pass. Thinking we could not wait, I drove out onto the bridge and at high speed raced toward the other end straight at the oncoming trucks.

The Vietnamese military drivers began sounding their powerful truck horns and waving to me to back off. They were not about to back down from a smaller civilian vehicle. But I just kept coming and when I got up close to the lead truck, I leaned out the window and yelled in Vietnamese “bi thuong nang, bi thuong nang, indicating that someone inside was “gravely wounded.’”

“I assumed incidents like this must happen all the time.”

Nothing out of the Ordinary: Whether it was out of compassion because they understood what I was saying or a judgment that I was crazy and never going to back up, the military drivers did the unthinkable and backed their trucks off the bridge. I swerved around the lead truck and off the bridge and drove the last few hundred meters to the entrance to the military hospital.

Once there, I had to use Vietnamese to shout my way past a non-English speaking sentry, so I could drive in and begin looking for the emergency room. All those months of language training were paying off. We were soon there and the hospital staff rushed out and helped carry the apparently lifeless young boy inside.

Having done as much as I could and believing the boy was dead, I went back to work. When I told the PSA and others at our office what I had just encountered and what I had done, it didn’t evoke much interest or reaction. I assumed incidents like this must happen all the time.

“Your getting him here so fast saved his life.”

Miracle Worker: Later in the afternoon, out of curiosity I went back to the hospital, expecting I would be told that the young boy had either been dead on arrival or had died shortly thereafter. I was therefore surprised when one of the Vietnamese military doctors greeted me and led me into the ward where the young boy, now surrounded by his family, was lying in bed, his eyes open and his stomach heavily bandaged. The family seemed incredulous that the boy had survived, but only nodded when they were told that I was the person who drove him to the hospital. As the doctor escorted me out, he said to me that at first they did not think the boy would survive, but he added “your getting him here so fast saved his life.”

“It brings home to me in a way that few other things could—a lesson I learned later in life—that the greatest treasure of being a father is the love you feel for your children.”

A Father’s Hug: The next afternoon as I was leaving the provincial headquarters where our offices were located, an older Vietnamese man wearing ragged clothing approached me. It was the young boy’s father. They were obviously a poor family. Without saying a word, he reached forward and grabbed my right hand with both of his hands and then in a most unVietnamese-like gesture came forward and pressed his body onto my arm and squeezed as tight as he could. It was a hug I have never forgotten.

Then keeping hold of my hand, he started to lead me across the road and down the bank of the Sa Dec Canal toward a very rudimentary restaurant. We had what was the equivalent of the best table in the house, except there was no house -just a totally open-air setting with a wobbly table and several little three-legged stools set on the muddy bank just a few feet from the edge of the dirty river. The man ordered the specialty of the house, an entire chicken, whose head was unceremoniously chopped off with a cleaver right in front of us. The decapitated torso of the bird, still driven by the last impulses of nerves and energy, tried to fly away but fluttered into the Mekong just a few yards out. The restaurant owner waded in and dragged the headless chicken back to shore where it was plucked clean and then cut up and fried. It was delicious washed down with Vietnamese beer which the father ordered.

I tried speaking to the father in Vietnamese, but never imagining I could speak his language, he just seemed to tune me out. All through the meal there never was a sentence spoken by him, only a constant, wonderful smile on the father’s face and a look of deep gratitude and affection in his eyes that he never took off me.

When we finished the meal, he squeezed my hand again and we then went our separate ways. I never met him again or his son. But I can remember to this day the look of supreme happiness on the father’s face and the feel of him intensely holding my arm. It brings home to me in a way that few other things could a lesson I learned later in life—that the greatest treasure of being a father is the love you feel for your children.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in Political Science, Loras College 1960–1964

MA in Political Science, Marquette University 1964–1965

Ph.D. in International Relations, University of Maryland 1965–1968

Joined the Foreign Service 1967

Sa Dec Province in Military Region 4, Vietnam—Rural Development Officer 1968–1969

Duc Ton, Vietnam—District Senior Advisor 1970–1971

Phnom Penh, Cambodia—Ambassador 1996–1999