It’s very common for Peace Corps volunteers to feel disheartened, as David Greenlee did as a Peace Corps volunteer in Bolivia during the 1960s, when they seemingly fail to make a difference in the communities they serve. It’s also never clear right in the middle of a volunteer’s two-year tour what impact the experience will have on their own lives—that often only becomes clear in retrospect, after leaving the country and spending some time away.

It’s also relatively common for many Peace Corps volunteers, like Greenlee, to go into the Foreign Service. But among diplomats, his professional life is remarkable in how intertwined it was with the country of Bolivia. He first returned in the 1970s as a political officer at the U.S. Embassy in Bolivia, then as deputy chief of mission in the 1980s under Ambassador Robert Gelbard––a fellow Peace Corps volunteer who had served in Bolivia just one year behind Greenlee––and then finally as ambassador himself, in 2003.

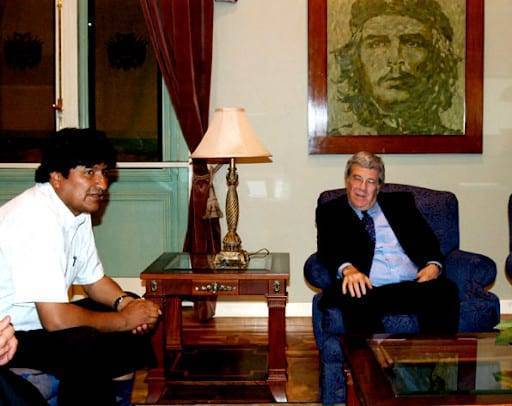

This Moment in U.S. Diplomatic History, the third in a series of Moments commemorating the 60th anniversary of the Peace Corps and the enduring connection between the Peace Corps and the Foreign Service, includes excerpts from Ambassador Greenlee’s Oral History interview. They include descriptions of his Peace Corps service and subsequent postings as DCM and ambassador in Bolivia, and they illustrate in broad strokes the changes that took shape in Bolivia over those decades. Greenlee saw many of those changes, especially from the perspective of U.S. interests and long-standing U.S.-Bolivia relations in a negative light, and represented in large part by Evo Morales, who became president during Greenlee’s time as ambassador.

David Greenlee’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on January 19, 2007.

Read David Greenlee’s full oral history HERE.

For more Moments on Peace Corps volunteers who became ambassadors click HERE.

Drafted by Daniel Schoolenberg

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

“In all but an anthropological sense, for me, it was wheel-spinning.”

Peace Corps Service (1965–1967)

Q: Had you picked up anything about Bolivia before you got into the Peace Corps?

GREENLEE: Actually, not. I didn’t know anything about Bolivia. When I was accepted for training, I did a little reading about Bolivia, and I knew that it was in the center of South America and there were high mountains. The rest I mostly learned about in training.

Q: What was the impression they gave you in training about Bolivia?

I was impressed by the organization that went into Peace Corps training and the standards that were set in the training. There were people, though, who were brought in on contract to talk about Latin American culture and who, in retrospect, were not very professional. They came out of the academic community. By and large, though, I thought the training was quite good, and there were a couple of Bolivians there. One, particularly, made an impression on me. His name was Joaquin Ferrufino and he taught me Quechua. Several of us took Quechua, because we already knew Spanish. By coincidence, Clara, the woman I later met and married, turned out to be related to him.

I was sent to a mostly Quechua speaking town called San Benito outside the city of Cochabamba. It was a highly politicized area. I was to partner with village-level workers who were supposed to be chosen directly by the people. That was rarely the case. The first thing was to help them conduct a survey to find out who was out there and what their problems were. The idea was that we would always deal with felt-needs that the people would identify. We would work with the village-level workers to develop a request for help from one of the central government ministries, for example the Ministry of Agriculture and Campesino Affairs. The Ministry, with USAID behind it, would provide materials and engineering support. The campesinos would put in sweat equity.

Some volunteers were successful in their areas. I was not. I lived in a little adobe house with a tin roof on the outskirts of town. One room, no electricity, no water. I had to go into town to get water and carry it out in a pail. I had a latrine and a Petromax lantern. The town, at night, had about 200 people. By day it was empty. I didn’t work there, but in the area around it. I started out with a bit of uneasiness. How should I start? What should I do? The people identified as my village-level counterparts were by and large appointed by the local political leadership. They had little interest in the program. They just wanted the goods. It was interesting dealing with them, but in all but an anthropological sense, for me, it was wheel-spinning.

For a while I had a horse. But the horse kept getting away and eating alfalfa from some guy’s field. It was a problem. Once I rode the horse with some Bolivian guys who also had horses to a town far up a mountain trail. We chewed coca, with a lye-like catalyst called lejia. The lejia, mixed with saliva, separates alkaloids from the leaf and produces a mild stimulant. This is not cocaine. It doesn’t create a high, only a deadening sensation. It’s what the miners and workers chew to ward off cold and increase stamina. In Bolivia, particularly in the higher altitudes, like La Paz, most people drink infusions of the coca leaf, which has a milder effect. It’s part of Bolivian life, with strong cultural overtones.

Q: This first assignment, were people saying, “OK, fine, you’re here. What are you doing for us? What are you really doing?”

GREENLEE: Right. That was exactly part of the problem: You are here, it’s wonderful you are here, we need things, we want you to deliver. They could never quite figure out what I was supposed to be doing because, in fact, it was hard for me to figure it out. Ascertaining their “felt-needs,” and how these could translate into the possibility of solid projects and getting resources through the government ministries, was too theoretical. The campesinos I worked with were used to handouts, usually just before an election, and broken promises. What was I bringing? Where was it? When would it come? That was the mindset.

Q: Sometimes Peace Corps people or AID people act as intermediaries. They say, they need more rice or cement, and I can help. Were you playing that role at all?

GREENLEE: I was, but none of the projects that we talked about really delivered to expectation. I think other volunteers, in some cases, had better results. But I learned a lot, an awful lot.

Q: Did you have any thought about the foreign service at this point?

GREENLEE: I did in the sense of the interest that had been sparked my junior year in Spain. Whenever I asked about the foreign service, though, I heard it was impossibly hard to get into. The tests, written and oral, were said to be daunting. I did know one volunteer, a year ahead of me, who entered the foreign service right after the Peace Corps. That was Robert Gelbard. Bob had a very distinguished career, which included being ambassador to Bolivia. I was his DCM (deputy chief of missions) for about a year, from 1988-89. I don’t think the Peace Corps ever realized how unique this was—an ambassador and DCM, serving together in the country where they had been volunteers. It was really remarkable if you think about it.

“I knew that no one had the background that I had.”

DCMship (1987–1989)

GREENLEE: I set my sights on deputy chief of mission in La Paz, because I knew that no one had the background that I had. I’d been in the Peace Corps there and had been a political officer there. I even knew some Quechua. But I was below the required rank, and there were officers at grade who wanted the job.

I remember thinking that I could get squeezed out by somebody who didn’t know the area and probably didn’t really want to go to Bolivia, anyway. I went to see Bob Gelbard, whom I had known in the Peace Corps and who was now a deputy assistant secretary in the American Republic Area (ARA) Bureau. I lobbied him. I said, “Look, Bob. There’s nobody who could do that job the way I can do it. There’s nobody with my background and experience. There’s nobody who knows a native Bolivian language…” Bob thought a second and said, “Well, there is so-and so,” mentioning a guy at grade who had also been in the Peace Corps with us and who was trained in Aymara. Bob let me twist a little bit, and then said, “But we’re sending him someplace else.” So the ARA door was open and I was put on the short list.

Q: What was the situation in Bolivia in 1987?

GREENLEE: Bolivia was in a comparatively rare period of stability. The president of Bolivia was Victor Paz Estenssoro, who had been the leader of the 1952 revolution. He was a very shrewd politician and a great statesman. He was able to pull rival parties and factions behind him on a general way forward. The objective was to achieve some degree of cooperation within the context of political competition so that the country could get out of its economic quagmire. When he came into office inflation was running over 20,000 percent. Paz was given rein to adopt significant economic reforms.

The U.S. supported Paz’s drastic corrective measures. With the economic direction of the country on a more rational course, our most acute concern was the over-production of coca and the growing traffic in cocaine. Our assistance in the areas of interdiction and alternative development began to increase. We pushed USAID to get involved in crop substitution in the coca-rich Chapare area of Cochabamba—which our AID director was reluctant to do. There was a significant police-training program, and DEA officers accompanied the Bolivian police on drug raids.

This was the beginning of Evo Morales’ rise to political power. He was a leader of the Chapare coca-growers and took the free-market position that the coca leaf itself was innocent, and the growers were innocent, and what others did with the leaf was someone else’s problem. I recall that, in the late 1980s and early ‘90s, he likened it to the manufacture of arms. The problem wasn’t arms but how they were used. It wasn’t coca, but how it was used. As deputy chief of mission I was the embassy’s anti-narcotics coordinator. I held daily meetings but was not involved in the actual planning of the interdiction or eradication operations.

“I said truthfully that returning to Bolivia was like coming home.”

Ambassadorship (2003–2006)

Q: It seems incredible that somebody who had been a Peace Corps volunteer, political officer, and DCM in Bolivia, and who had a Bolivian wife, could return to Bolivia as ambassador.

I wasn’t looking for any further ambassadorship, really, but I did note around March of 2002 that Bolivia was unexpectedly coming open. So I put my name in. I was told, though, that the post would be filled by an assistant secretary in another bureau, not WHA. So I figured that was that. Then a few weeks later I got a call. The acting assistant secretary in WHA, Lino Gutierrez, said, “I understand you’re interested in Bolivia.” I said, “Yes, of course, but what about that other guy?” He said he had decided to retire instead, and that WHA could submit a name. It wasn’t a sure thing, but the deputy secretary’s committee ultimately selected me and I got the nomination.

I asked permission to do a direct transfer from Paraguay to La Paz. I was told it was unusual but possible, and we made the arrangements… We got on a Lloyd Aéreo Boliviano (LAB) flight from Asuncion to Santa Cruz, Bolivia, and transferred there to another flight to La Paz… We were met by the country team and there was a small press event. I said truthfully that returning to Bolivia was like coming home. That was how I felt, and how my wife felt. Two of our four children, our daughters Nicole and Gabrielle, certainly felt that way as well, as both have Bolivian as well as American citizenship.

Q: How were American relations with Bolivia?

GREENLEE: Relations had always been good, but very asymmetrical. The U.S. was the biggest bilateral assistance donor. Until Evo Morales was elected president at the end of 2005, the U.S. was always courted, paid deference to, because of that. But our presence was overwhelming. We were too big, the way we did things, was too big for the bilateral relationship. It was bad for Bolivia, and it was bad for us. The Bolivians were in the habit, the bad habit, of being supplicants, and we were in the position, the frankly arrogant position, of doling out assistance. The Bolivians wanted help without conditionality, while we needed to know that our aid wasn’t being squandered, that it was going to something that had a developmental purpose or an anti-drug purpose. The Bolivians resented the emphasis on drugs.

Q: How did the press deal with your arrival, or were you an important factor?

I came into the country with a headwind. There had been a disinformation campaign against me before I arrived. It was launched by the people who are now running the country, Evo Morales’ people. As DCM I had been the anti-drug coordinator, and the MAS, or their surrogates in the press, accused me of having masterminded confrontations in which coca growers had been killed.

Even before I arrived in Bolivia, Evo Morales was saying that if he were killed, everyone should look to me as the culprit. This kind of thing is still all over the internet. Ideological journalists, really quite creative people, wove shreds of information from my curriculum vitae—that, for example, I had been in Vietnam and present during various coups in Bolivia—and suggested that I was a trained killer and expert in toppling governments.

In Bolivia people tend to believe the most provocative, crazy rumors, so I had that to overcome. At the same time, I think there was a certain fascination with my Bolivia experience, and also that my wife was Bolivian. It helped as well that my wife is very photogenic, that she is a great artist and a great organizer. She raised a lot of money for Bolivian charities and, to the extent I was seen as trying to help Bolivia, people tended to see my wife’s guiding hand. That was all to the good.

“I left post with the regret that I couldn’t do more.”

Morales Becomes President

The elections were on December 5. We expected a close outcome, but Morales won in an historic landslide. He won 54 percent of the votes. There was no need for a congressional runoff. It was a blow-out. We were surprised. The polling data, never good in Bolivia, didn’t show a victory of this magnitude coming.

Q: And in the immediate aftermath. What did you do?

I looked at this new reality as an interesting challenge. A few weeks after the election, but before his inauguration, we suggested to Morales’ people that we meet, and he readily agreed. He came to my residence with the vice president, and we sat down at a table. I had my DCM and a political officer with me. The meeting was difficult, quite tense, actually, but on the whole positive. Before we started, I introduced him to my wife and Spanish daughter-in-law and our grandchildren, who were visiting. I think one of my daughters, Nicole, was also there when he came in. I told him that she as well as my wife were Bolivians. He just nodded. I think he was quite uncomfortable.

I told him that our relationship would depend on a couple of fundamental things. On tone, it was essential that he stop insulting my president and my country. On substance we had to find a way to address the cocaine problem. He of course had his own agenda, but where we came out was that we should turn the page, try to move forward. I thought it was a good start.

But for him it was an economic problem that drove the political reality in which he had to operate. So he made the argument that the coca leaf was benign, even good for humanity, but cocaine was bad—a product consumed in the developed countries. So what was needed was a greater concentration in blocking the traffickers, on interdiction, and less focus on coca production—particularly coca cultivation in the Chapare, his political base. He argued that there could be “social” control of cultivation. Each family would be entitled to a limited coca plot and the syndicates, or unions, would restrict the size of other plots. It was simple economics. Control of supply would keep prices up.

This wasn’t the coca policy that we wanted, but it was the one we were stuck with. Our DEA noted that there was good cooperation on interdiction. So both sides could say there was a way forward. But at bottom we all knew—and, again, all Bolivians know—that more coca means more cocaine. Bolivia under Morales is returning to that business, no matter how he and his cohorts try to dress it up.

On the political side, our relations quickly deteriorated. Morales couldn’t stop attacking us. Partly, I am sure, it was his personal resentment, still occasionally stoked by intemperate remarks from Washington. The problem there was not the State Department. But off-hand comments, here and there, would give him something to work with. Once Defense Secretary Rumsfeld, for example, said something sneering about Morales on a visit to Paraguay. It played to Morales’ hand, not ours.

I left post with the regret that I couldn’t do more to shore up a bilateral relationship that had become too one-sided, but which in the end was the relationship that Bolivia most needed. It will take years for the social revolution that Morales is trying to direct to burn through. On the positive side, Morales has demonstrated that a Bolivian of any ethnicity can become president. On the negative side, he has harnessed South America’s poorest country to a losing ideology and deepened divisions in the country that he could have bridged.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in English, Yale University 1961–1965

Peace Corps

San Benito, Bolivia––Volunteer 1965–1967

Joined the Foreign Service 1974

La Paz, Bolivia––Political Officer 1977–1979

La Paz, Bolivia––Deputy Chief of Mission 1987–1989

Madrid, Spain––Deputy Chief of Mission 1992–1995

La Paz, Bolivia––Ambassador to Bolivia 2003–2006