This moment is one of four in a series about Russia, Ukraine, and U.S. relations in a world of post-Ukrainian independence. The series, “From 1991 to 2022: Russia, U.S., and Ukraine Relations,” explores how the post-Soviet Union era presented unique challenges to each nation’s foreign policy.

The reignited tensions between Russia and Ukraine pose important questions about how the nations’ histories inform the conflict today. The four moments in the series— U.S.-Russia Competition in Ukraine in the ‘90s, Russia-Ukraine Tensions, Ukrainian Nationalism in an Independence Era, and Beginning a U.S.-Ukraine Relationship—seek to shed light on the 2022 conflict between Russia and Ukraine by examining its history.

The recent Russian invasion of Ukraine might appear relatively sudden and confusing. The unprovoked Russian aggression certainly brings about more questions than answers, but disagreements between the two nations have been setting the stage for decades. National identity, territorial integrity, Soviet-era legacies—each of these themes presented a unique challenge for Ukraine-Russia relations in the aftermath of Ukrainian independence.

Ukraine had to manage a territory with its own national identity while navigating the remnants of a Soviet society. On the other hand, Russians were confronted with a “Ukraine” that was newly separated from their culture and national identity. As a former member of the American Committee on U.S.-Soviet Relations turned Ambassador to Ukraine, Ambassador William Green Miller was uniquely apt to handle the post-Soviet Union tensions. In this “Moment in U.S. Diplomatic History,” we learn from him about some of the major misalignments that continue to inform Ukraine-Russia tensions to this day.

Drafted by Aubrey Molitor

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

William Green Miller’s interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on February 10, 2003.

Read William Green Miller’s full oral history HERE.

Check out our other moments on Ukraine HERE.

Read the other moments in the series:

U.S.–Russia Competition in Ukraine in the ‘90s

Ukrainian Nationalism in an Independence Era

Beginning a U.S. – Ukraine Relationships

Excerpts:

“Dealing with those lingering legacies of the party of power, of the Soviet man… won’t cease to be a problem until there’s a passage of generations who deal with it and understand that it has to change”

Legacies of the Party of Power

Q: I would think that, looking at it purely in self interest, that to keep Ukraine out of too close of embrace or being part of Russia would be of great advantage to us, because it essentially would mean that, without Ukraine there and it’s 40 million people and it’s land mass, it just means that Russia is not going to be the powerhouse that it was before.

MILLER: Well, that was the rubric that was laid down and accepted by many political analysts. This rubric was formulated and laid down by Brzezinski. This was his thesis, and it was held by others, but the great question about it was this – and would it be viable? Would the differences between Ukrainian-speaking portions, the West and the East, divided by the Dnipro, split the nation? Would Crimea revolt? Would the Russians balk on agreements to division of assets such as the Black Sea Fleet? These were all unknowns, great doubts, and we didn’t know the new players particularly from Ukraine.

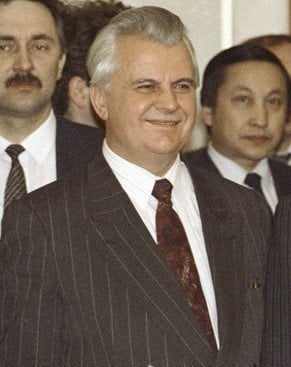

No one in the Clinton Administration knew the players in Ukraine’s new government, and those few that they had met, they didn’t like. They thought they were equivocators. They believed they couldn’t be trusted to hold their word, which really meant they didn’t agree with them, and they were stubborn and difficult and awkward and unpracticed, which is quite understandable. Kravchuk, the president, was a second or third-rank nomenklatura (Communist bureaucracy).

Q: Who was that?

MILLER: He was the president of Ukraine.

Q: But his name?

MILLER: Leonid Kravchuk, the first president, a Communist, I would say held economic views that could be described as Gorbachevian, was definitely a Ukrainian nationalist, but a supporter of independent Ukraine because he saw no other way. The Soviet army would no longer work to keep the Soviet Union whole, he was convinced, but his future and the future of the party structure, of which he was a part, now had to lead and dominate a newly independent Ukraine. The question of whether it would ever be back in union with Russia was too far down the road. For Kravchuk and others it was an immediate question of how the party of power would stay in power. Kravchuk concluded that Ukraine led by him and his allies could only stay in power if Ukraine was an independent, sovereign state. That evolving notion of a “Party of Power” is something that still is very difficult for our policymakers to comprehend, namely: that in Russia now and in Ukraine now in 1993, the party of power is composed of the same people who would be in power if the Soviet Union had never split.

Dealing with those lingering legacies of the party of power, of the Soviet man, of the Soviet bureaucrat, the Soviet-trained teacher, professor, scientist, military man, KGB, every field that you could think of—bankers, entrepreneurs—is still the major problem. It won’t cease to be a problem until there’s a passage of generations who deal with it and understand that it has to change and move on to something else.

High level meetings with Kravchuk and his aides were difficult, and the meetings that they had at the diplomatic level with the new foreign ministry were even more so. The foreign minister, Anatoly Zlenko, Borys Tarasyuk, Gennady Udovenko, and the NSC advisor, Anton Buteiko, these were the key players Americans had to deal with. They were intensely nationalistic, uncertain about U.S. motivations, not as experienced or as at ease with Americans as their Moscow counterparts, and they felt those differences.

“From the outset, when they enunciated it, the new independent Ukraine understood 189 that message and saw this policy by Russia as a threat to their sovereignty.”

Russia Claims its Sphere of Influence

MILLER: Well, the Russians in Moscow from the outset of the new Russian state in 1991 had declared their “near abroad” policy, which meant, “Our natural sphere of influence includes Ukraine, Belarus, the Baltics, all the ‘stans, the Caucasus, historic, imperial Russia, the Soviet Union. This is our near abroad, and this is where we have a right to be.” From the outset, when they enunciated it, the new independent Ukraine understood that message and saw this policy by Russia as a threat to their sovereignty. They expected, correctly, to see interference in their internal affairs, political and economic pressures brought to bear.

The most difficult immediate strains between Moscow and Kyiv were in Crimea, the majority of Crimean political parties were pro-Russian, particularly the Communist Party. At the moment of independence, Crimea had voted for union with Ukraine. It was very evident that after several years, that the Russian population in Crimea was restive, that they didn’t like the new Ukraine, partially because of the extreme economic distress, but also because the cutoff from the normal amenities of Moscow. That was evident in the resorts and the natural flow of goods and services, even the winemakers, makers of champagne, wonderful Ukrainian champagne such as Novy Svet, had lost their markets. Even though money in the old days wasn’t the issue, production levels were; now it was money that mattered

The “Black Admiral” and Ukrainian Territorial Integrity

MILLER: … A coalition of pro-Russian parties, composed the majority in the parliament of Crimea. This majority declared Crimea a republic, an independent republic. Moscow didn’t formally recognize the new republics but they didn’t declare them breakaways either. I traveled to the region of the independent Republic of Crimea as the United States Ambassador to Ukraine. I went first to Sevastopol, which was in fact being governed and really run by the Russian commander of the Black Sea Fleet. The commander of the Black Sea Fleet was very suspicious of the purpose of my visit. He had been a submariner, a nuclear submariner, who had commanded strategic nuclear submarines that patrolled off the east coast of the United States, fully armed. For many years, Admiral Eduard Baltin had been a leading officer of the nuclear fleet of the north. He had also served in the Pacific. He was a major naval officer in the Soviet armed forces and now the commander of the Black Sea Fleet. The Black Sea Fleet was an uncomfortable joint command of the combined Russian and Ukrainian navies stationed in the Black Sea.

So I asked to see him… Admiral Eduard Baltin, known as the “Black Admiral,” was a very, very interesting, charismatic character. We had extraordinary talks about many subjects ranging from strategic issues, arms control, the future of Russia and Ukraine and considerable discussion about seafaring novels ranging from Moby Dick to Tom Clancy’s Hunt for Red October. All of this talk was stimulated by an enormous amount of wine and vodka and cognac, several huge meals. We toured several of his capital ships. He was most concerned about the issue of whether the new Ukraine would survive? His interest was political. He asked me very directly, “How do you see Ukraine.” I assured just as directly, “I see it as an independent republic, and I see Crimea part of Ukraine.” And he said, “No, Sevastopol is Russian. It can never be otherwise. It is a part of Russian history. Many of our heroes are buried here. Most people who live in Sevastopol are Russians. Look at the battlefield.”

I said, “I understand the treaty with the Russians, but I’m here to say that the policy of our government is that we support the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine. This is part of Ukraine. I fully understand the history of Crimea and I know it is deeply tied to Russian and Soviet history. But the Soviet Union is dissolved. Russia and Ukraine are legitimate successor states with separate sovereign territories. Ukraine and Russia share a common noble history and have every reason to live at peace with each other. But I’m here to pay my respects to you as commander of the Unified Black Sea Fleet.” I said, “How do you see Ukraine?” He said, “I see Ukraine coming back to Russia. I look on it like Canada, the way you see Canada.”

I said, “Canada is a separate sovereign nation.” He said, “No, they’re dependent on you.” So we had many discussions along those lines. Near the end of our talks I said, “Would you come to the United States for a visit and talk to our new naval people perhaps at the Naval War College at New port near my home in Rhode Island? They’d be very interested in your experiences as a submarine commander.” He said he would like to. He had seen my country from outside the coastal territorial boundaries. I asked Baltin, “Three miles or six or twelve miles?” He answered, “just outside the legal boundary.”

Q: Through a periscope.

MILLER: Yes. I saw him a number of times later. As I learned later, Baltin reported to Moscow that I was a formidable person, probably CIA. He concluded that the Americans are pursuing a very active policy that has to be countered.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Background

William & Mary, Goethe Institute, Oxford, Harvard

Joined Foreign Service 1959

Iran, Vice Consul and Political Officer 1959–1965

State Department Executive Secretariat 1966–1967

Resignation 1967

Post Resignation activities:

Chief of Staff, Senate Select Committee 1972–1976

Senatorial Intelligence Oversight Committee 1976–1981

American Committee on U.S.-Soviet Relations 1986–1992

Ambassador to Ukraine 1993–1998