Haiti has been plagued with instability for much of its existence, despite being the second country in the Americas to declare independence. The U.S. and United Nations (UN) have been involved in Haiti since 1993 as a multinational force, peacekeeping mission, and crisis response network. However, the creation of a long-lasting secure government has eluded Haiti. Historical experience can serve as a lesson for future UN missions to consider methods other than using force alone to create security in countries at risk of failing.

The first UN Mission in Haiti (UNMIH) was commissioned by the Secretary General in September 1993 but was unable to deploy until 1995 due to non-cooperation by the Haitian military. It was finally deployed after a U.S.-led multinational force helped establish the Haitian Constitutional Government in October 1994. During UNMIH, Haiti successfully held democratic elections in December 1995 and the successful transition of power in February of the next year.

UNMIH’s mandate ended in July 1995 and was replaced by the UN Support Mission in Haiti (UNSMIH), whose much narrower mandate focused on establishing and professionalizing the Haitian National Police (HNP), while helping it keep the relative peace that had been established. UNSMIH was replaced by the UN Transition Mission in Haiti (UNTMIH) in August 1997, which had much the same mandate. However, none of these missions successfully established a HNP capable of maintaining security once the peacekeeping force left.

According to the Special Representative of the Secretary General Julian Harston, who was stationed in Haiti in 1997–1999, the mission of institution building in Haiti was often stonewalled by the inability of Haitian political actors to accommodate. As he puts it, “they simply didn’t seem to understand the need for compromise.” In his three years in Haiti, Harston feels little was accomplished in building democratic norms or institutions.

However, as we see in this “moment” in diplomatic history, Harston believes blame should not be placed on the Haitians alone, as the failure of the mission in Haiti to establish a lasting government or police force embodies larger failures by the UN and its stakeholders to understand how missions should approach institution building. In his opinion, the peacekeeping missions in Haiti show once again that security-only interventions in failing regimes do little to address why the insecurity exists in the first place. Instead, the UN must learn that mandates to establish security must be accompanied by an effort to establish a government capable of providing basic education and health to its citizens.

Julian Harston was the Special Representative of the Secretary General in Haiti from 1997 to 1999. Before Haiti, Harston was in the U.K. Diplomatic Service for 25 years, with postings in Southeast Asia and Africa. He then joined the UN, serving in the Balkans on three occasions, as well as Western Sahara. He was appointed Assistant Secretary General in 2007. Harston retired from the UN in 2009.

Julian Harston’s interview was conducted by Biljana Jović on April 12, 2021.

Read Julian Harston’s full oral history HERE.

To read another moment from Haiti’s struggle to establish democracy, click HERE. For information about the 1991 Haitian coup, click HERE.

Drafted by Calvin Heit

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

“The situation in Haiti, not to put too fine a point on it, is always awful.”

The Haitian Situation:

The situation in Haiti, not to put too fine a point on it, is always awful. There was a political stalemate in Haiti. They had taken some time to come around to elections. The law-and-order situation was pretty awful. That’s not to say anything about the fact that Haiti was then and is now a failed state. Haiti produces children and cuts down forests, and if you do that for long enough, you fail. And if you have as Haiti does, a middle class, a political class, which doesn’t care about Haitians or Haiti, then it makes it even worse.

It’s a very depressing place to be, if you’re an ordinary Haitian, but also if you’re an outsider with an objective point of view, and you can’t see progress. It’s a very destructive society. And it’s a very difficult place to live if you are observing politically because there is no responsible political class. If you look at what’s happening now, it’s not very different from what was happening then. Now you have a prime minister who is on the run, because of the enormous demonstrations against him and his regime. A man who became president because he can sing. It was very difficult for me.

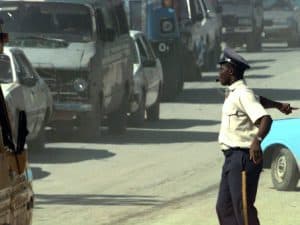

It was an enormous cultural shock for me, because even though I’d spent years of my life in Africa, I had never seen poverty like there was in Haiti. I’d never seen the state of roads. It took me an hour and a quarter to drive fifteen kilometers from my home into the center of Port au Prince. We had a relatively small police mission with the simple responsibility of creating and running a new police force for Haiti. There were no armed forces. The armed forces were disbanded when Papa Doc (François Duvalier) and Baby Doc (Jean-Claude Duvalier) , his son, left. So, there was no military, there was just police. We were responsible for creating, running, and training a new police service….

I spent all my life in diplomacy and then in peacekeeping and going to meetings—we were talking about meeting Milošević, or meeting people here or meeting people in Bosnia or whatever. There were always meetings where you came back to your office, or you went home afterwards, and there was adrenaline, you thought, “that guy I’ve just been talking to is really going to do something. He’s going to make a difference. That woman is going to make a difference to whatever she’s involved in.” It never happened to me once in Haiti. I never came home or went back to the office thinking, yeah, okay, that was a good meeting, those folks are actually going to do something. Never. And that’s pretty depressing after a year or so. It was difficult not to become cynical….

In Haiti, they simply didn’t seem to understand the need for compromise in politics or anything else. After all, they’d lived for some considerable time under dictatorships of one kind or another. And where there have been no compromises, there have been no discussions, have been no ability to change the course of events. So, I suppose they’d got out of the habit, but maybe it also has something to do with the background of nations. I don’t know. But there was very, very small room for compromise in almost anything.

“We never asked the Haitians what they wanted.”

The UNTMIH Mission:

The police mission was created a couple of years before I got there. While I was over there was an Argentine guy who was my predecessor. We just simply had, as I say, the responsibility for creating and managing a police service and for political offices of the Secretary General. I mean, obviously, one of the other lessons I learned in Haiti, was that the UN at that time… we never asked the Haitians what they wanted. We never sent a mission to Haiti before that police mission started saying, “Look, we’re going to start a police service, what sort of police service do you want?” No, no, we came along as the last great colonial organization in the world and said, “Here we are, we know how to run police, this is what you’re going to have.”

We tried to give them a mixture between the Canadian RCMP soft community policing approach and a bit of Special Forces approach from the Argentine Gendarmerie. And they didn’t want any of that. What they wanted in the countryside was uneducated… policemen who would understand and care if somebody had stolen your chickens. Not people, who the moment they got into uniform behave badly. Which is what they got. What the people in town wanted was special police armed to the teeth to deal with criminals and to bring law and order into a society, parts of which in Port au Prince were totally lacking in law and order. We didn’t give them that either. So, it was no surprise to me at all five years later to see the police service collapse, which it did. Disappointment, but not surprise.

I think the problem in Haiti was that the UN was invited to come in to do a very specific job, which was to run the police service. We were not a military mission, we had armed Argentine Gendarmerie, but they were there to protect us, not to protect the Haitians. So, we were given a limited function. But it was a big presence. You know, we had all our vehicles and so on, and my Gendarmeries had armored personnel carriers. So, we had a military force of a kind. But this is the dichotomy. This is the problem of peacekeeping, wherever you are, there is almost immediately a resentment and it’s frequently over silly things.

We replaced a lot of our vehicles for the very first time when I was there. And the Haitians lay down on the street to prevent us from taking away the old vehicles, because they said, “Oh, but they are ours. These were sent to Haiti for us.” Well, no. You know, I think we could have handled it more sensitively. But the rules said, you have to ship them out. So, we did. It’s, if you like, it’s one of the key problems of peacekeeping, people don’t actually like to be helped.

“The military cannot create societies. They can create a platform on which all the rest of these things can be done, but essentially the problems are political.”

Lessons Learned:

I suppose as far as peacekeeping is concerned, the most important message I got from [my time there] was how little preparation the UN did in those days before embarking on a mission of that kind. Now, nobody had ever asked the Haitians what sort of police force they wanted. Few of the people operating there, from the internationals operating there, in the mission had ever had one hour of training in the history or the culture of Haiti. We really did behave like the last of the colonial powers. And, of course, as far as creating a police service that the Haitians wanted—as I said to you before—I think it was no surprise to me at all that, five to ten years later, the police service we had created collapsed. And I suppose that was the most important lesson.

There were plenty of others, and one of them, unfortunately, was a feeling that Haiti is just doomed as a country. I can see no hope for Haiti because of the crucial elements that they produce too many children, they mistreat their land, and they have no responsible political class. So, I can’t see Haiti ever being very much different from the way it is now. I mean, properly managed as a country. It has potential agriculturally; it has potential with it. It has a vast potential for tourism. It has one of the most beautiful coastlines in the world and the warm Caribbean Sea. It will never be rich, but it should never be poor. But it will be. And, you know, it is very depressing because I loved Haiti, and I still love it.… It is a stunningly beautiful country. but it is just doomed by history, by its past, and by the way it is right now.

Well, of course, [finding a balance between security and development] wasn’t our responsibility. My responsibility was simply a security one. It was to form and manage a police service…. And the tragedy is—if you follow LinkedIn, or whatever, you’ll see that I’m constantly banging on about this—the fact is you can’t solve problems, whether they be in Chad, or Mali, or by simply imposing force, whether it’s French force, or whether it’s UN force. The military cannot create societies. They can create a platform on which all the rest of these things can be done, but essentially the problems are political.

And so even now, the UN talks about the problems in Mali, for example, and in Chad, and in Somalia as being problems of insurgency. Well, they’re not. I mean, insurgency is a problem, but, actually, if you apply the right amount of force to it, you can stop it. Or you can certainly make things better.

But you cannot do that, without a concomitant effort to solve the basic political issues, which create the lack of security in the first place. If you look at places like Haiti—you can also look at places like most of the places in Africa right now – there simply isn’t enough being done politically. And if you decide you can’t do it, then we shouldn’t be there either. You know, I think it is wrong for the UN, for example, to be in the Sahel and in Chad, and so on, because we are making no effort to solve the political problem. And we think we are involved in insurgency, why?

The French – I can understand. Europeans – I can understand, because they perceive it to be a threat to Europe, of instability in that region, a threat of immigration, a threat of terrorism, a threat of basis for terrorists and so on. They understand, that is their problem. I see no reason why a Bangladeshi should die in Chad. I go on saying that and eventually someone is going to tell me to shut up. But it just makes no sense for the UN to be involved in counterinsurgency, which is what it is.

What you want to establish, if you can, is a sustainable state of security. I am not a Democrat. I don’t believe that democracy, Westminster style democracy is a solution for anybody, not even the people in Westminster. But I do think that there is a basic minimum of delivery that people expect of their government. They expect their children to be educated, they expect there to be security, they expect there to be health, and so on. And so, you have to focus on a sustainable solution.

And one of the problems that we’ve seen with the Americans and NATO being involved in Afghanistan and Iraq and so on, is that they haven’t done that. And so now, the Americans are pulling out of Afghanistan, NATO is pulling out. And it will revert and by the end of 2021, Kabul will be in the hands of people that we regard as terrorists, and we will have achieved nothing in terms of creating the security that people are desperate for.

One of the clever things that these organizations, these people, we class as terrorists do, of course, is begin to deliver those goods and services that people want. So, if you look at Somalia, and you look at the areas that are not under government control, most of those services to people are provided by the people that we refer to as terrorists. So, what people want is stability.

When we first went into Somalia, many years ago, the first thing we did was to put up posters of a man who could actually have solved the problem. He was a terrorist, oh, he was a warlord, he was all the things that we call these people these days. It was a feudal society, of course he was a warlord. And, you know, Afghanistan has been a feudal society for 1000 years. You know, why do we go in there and say, “Well, actually, you’re doing this all wrong.” Instead of going out and saying, “Okay, it’s not our kind of place. It’s not our kind of democracy, but we want to help you deliver the things to the people that they want, in a sustainable way. So, education and health and so on, so forth. And we’re not going to make judgments essentially, about how democratic you are. We’re going to look at human rights, of course, we’re going to look at the protection of civilians and sum.”

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

BA in Economics, London University, 1960–1964

BA in African Studies, University of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, 1960–1964

U.K. Diplomatic Service 1971–1994

Joined the United Nations 1995

Belgrade, Serbia—Director, UN Liaison Office 1996–1997

Port-au-Prince, Haiti—Special Representative of the Secretary General 1997–1999

Belgrade, Serbia—Director, UN Office 2004–2007

New York City, United States—Assistant Secretary General 2007–2009