Diplomatic history is a fascinating field full of peace conferences, negotiations, and summits; but it also includes dozens of other jobs, like public diplomacy. Public diplomacy normally involves writing press releases and statements, planning public events, and managing public opinion; but it could involve taking astronauts on world tours, negotiating the excavation of a Confederate warship (yes, THAT Confederacy), or battling foreign misinformation. So what is it like to work public relations as a U.S. diplomat?

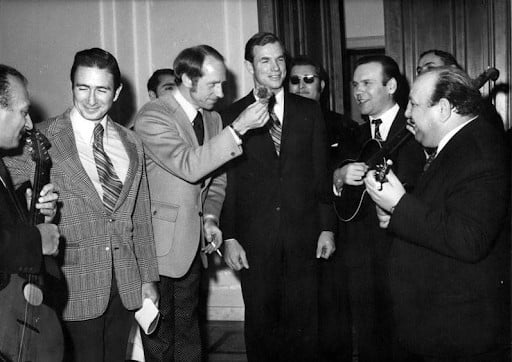

Irwin, left, Worden, and Scott meeting a Gypsy band in Novi Sad, Yugoslavia (1972) | NASA

This look at a career in public diplomacy, taken from Chris Henze’s memoir, illustrates the variety and excitement of the profession. Henze was from California, and had always dreamed of working overseas. After a stint in the Peace Corps, Henze took the Foreign Service Exam and joined USIA. During his time with USIA, Henze accompanied the crews of Apollo 14 and Apollo 15 to Poland, Yugoslavia, and Western Europe, coordinated displays of moon rock samples abroad, and was responsible for all the press arrangements for the 1985 summit between President Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev.

During his career, Henze directly encountered several instances of less-than-honest practices by U.S. officials, including the Iran-Contra Affair and a situation in which funds for the Fulbright Commission were being misused for parties and other expenditures. As he writes in his memoir, there were multiple times that his conscience would not allow him to stand by and watch dishonesty take place, which almost got him fired on more than one occasion.

In the end, however, Henze’s memoir illustrates how much variety, opportunity, and satisfaction a career in public diplomacy can provide.

Chris Henze’s memoir was written in 2020, and posted on ADST’s website with permission.

Read Chris Henze’s full memoir HERE.

Drafted by Calvin Heit

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

“[Astronauts] are some of the most impressive, intelligent, and courageous people I’ve ever met.”

Astronauts’ World Tour: I was privileged to facilitate foreign press coverage of several Apollo launches and can never forget the sound and shirt-flapping wave of sheer unimaginable power reaching us from four miles away as the tremendous rockets lifted off the pad at Cape Kennedy. You wouldn’t want to be any closer. Equally amazing was my, and just about everyone else’s involuntary, spontaneous shouting “Go, go, go” for the three brave astronauts as they began their trip.

I prepared the way and accompanied the Apollo 14 and 15 astronauts to Poland, Yugoslavia, and Western Europe, where they met with dignitaries and lectured to the scientific communities. One evening I cornered Al Worden in a hotel bar to ask him two questions that had long been on my mind.

The first was as Command Module Pilot orbiting the moon 71 times alone while his Apollo 15 teammates were on the surface of the moon: Were you very busy piloting alone and without your colleagues? How lonely was it? His answer: No, I wasn’t busy all the time, and frankly I was glad to be rid of them and have some time alone.”

OK. That led me to the big question. Did your experience in space affect in any way your religious feelings or thoughts about God?

His astounding answer: “Yes, I came to think of the astronaut as God.” Upon reflection, it made a lot of sense to me. After all, many religions emphasize that God is everywhere, in every thing and every creature.

Besides orchestrating the international travels of astronauts, I orchestrated the travels of the moon rocks they had gathered, for exhibition in foreign countries. Occasionally a rock would become dislodged from its mounting inside its plexiglass case filled with nitrogen for preservation. The disabled rocks then had to be returned to the Lunar Laboratory in Houston for resetting. I describe one such rescue mission in a separate little write-up, My Piece of the Moon.

Let me use this opportunity to kill off one misconception. Astronauts are not just glorified jet jockeys. They are some of the most impressive, intelligent, and courageous people I’ve ever met.

“Well, I did lie, once.”

When Honesty Isn’t an Option: When my French press assistant called me early in the morning about the failed Iran hostage rescue attempt, I notified the ambassador and waited patiently for Plan B to go into effect. It was not a diversionary tactic, and there was no Plan B. Fifty-two Americans from our embassy in Teheran, some of whom I knew personally, were held prisoner for over a year.

Now, here’s a big reveal. When I arrived in Paris, I told my staff I would never lie to the media. If they or I did so, we could pack our bags immediately since our credibility was of the utmost importance. We could stonewall or “no comment,” or tell a partial truth but never lie.

Well, I did lie, once. Important, highly secret negotiations were taking place in Paris. If they became public knowledge, there was every possibility our colleagues in Teheran could be killed. When asked about these negotiations by the media, I categorically denied they were taking place, a bold-faced lie. I live with my conscience.

“What a clear signal that the times they were a-changin’ back in the good old USSR. Boy, did I write that all up in a cable to Washington as soon as I got back to our mission.”

Dealing with the Soviets: As Counselor for Public Affairs at the U.S. Mission to the United Nations and Other International Organizations in Geneva, I managed all public affairs activities for the U.S. Mission, the U.S. Trade Representative’s Office and visiting U.S. delegations, including spokesman’s duties for our nuclear arms negotiators.

I was also responsible for all press arrangements for the first Reagan/Gorbachev Summit in 1985, for which I received the Agency’s Meritorious Honor Award. We had six months notice to prepare for the momentous event. It took me three months to wind down afterwards. I had made lists and lists of lists in my head, trying to imagine everything that could possibly go wrong. It all unfolded beautifully. Nancy Reagan did not scratch Raisa Gorbachev’s eyes out. Only I know what went wrong, and I’m not telling.

We had an inkling that Gorbachev was a new kind of Soviet leader. For example, I was invited to the Soviet mission to celebrate Journalists’ Day. There, in attendance, was a long- bearded patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church. The evening’s entertainment was a singer’s lovely rendition of Ave Maria. What a clear signal that the times they were a-changin’ back in the good old USSR. Boy, did I write that all up in a cable to Washington as soon as I got back to our mission.

The next economic summit was in Venice in 1987. I think White House Press Secretary Marlin Fitzwater noted my quick action in “clarifying” some words by Ronald Reagan that may have spared the world a financial crisis.

One of the battles I fought in Geneva, incidentally, with some success, was Soviet disinformation about the U.S. marketing “baby parts,” from the Third World for transplant into needy American children. Another was The Hunger Project (THP), which tried to infiltrate our international school. It collected a lot of money, but only did a good job of feeding itself, not hungry people. My actions to expose it nearly got me fired since THP had connections with USIA leadership.

“The Alabama story itself was fascinating – a ship secretly constructed in Britain, a dashing Southern captain who captured over 60 Northern merchant ships all over the world during a two-year period, nearly destroying Northern commerce and forcing insurance rates sky high.”

Preserving History: More interesting was coordinating all U.S. Government activities in France related to the Bicentenary of the French Revolution. We even managed to borrow back the key to the Bastille hanging on the wall at Mt. Vernon. It was given to George Washington by La Fayette, and we displayed it at the new Paris opera house at the Place de la Bastille.

One project that really grabbed me was the CSS Alabama. This Confederate raider was sunk off Cherbourg by the USS Kearsarge in the only battle of the U.S. Civil War outside American territory. The wreck lies 60 meters down in today’s French territorial waters. Its exploration was a complicated matter involving both governments, and was a first in international jurisprudence. The Alabama story itself was fascinating – a ship secretly constructed in Britain, a dashing Southern captain who captured over 60 Northern merchant ships all over the world during a two-year period, nearly destroying Northern commerce and forcing insurance rates sky high. (Captain Semmes even captured an enslaved person who chose to stay on with him as a valet and a free man. Sadly, David White could not swim and drowned in the final battle.)

I first came across the story in Geneva’s city hall when we were seeking a suitable site for the Reagan/Gorbachev summit. The Alabama Room there was not appropriate, but intrigued me. It was where the first international arbitration in history took place over damages caused by the Alabama.

I voluntarily and willingly acted as liaison between France and the U.S. in negotiations over ownership of the wreck. Our Naval Attaché wouldn’t touch it with a ten-foot pole, since he still considered the Alabama an enemy ship, which had badly humiliated the U.S. Navy. After retirement, I served as head of the Association CSS Alabama, responsible for joint French-U.S. exploration of the wreck.

My account was published in the University of Alabama’s Alabama Heritage, Issue 37, Summer 1995. For my articles on the Alabama, I was nominated for the USIA Director’s Writing Award.

“I was required to attend meetings where things were discussed that I wanted no part of. It became so bad and stressful that I could hardly look at myself in the mirror in the morning.”

Knowing the Truth: But it wasn’t all good. This was the time of Project Truth, Project Democracy, Ollie North and others engaged in or planning various nefarious activities. I was required to attend meetings where things were discussed that I wanted no part of. It became so bad and stressful that I could hardly look at myself in the mirror in the morning.

Shana and I were dinner guests of our French neighbors across the street. I was called away from the table too many times. A Soviet fighter jet had shot down Korean Airlines passenger Flight 007, and I had to manage the story for our newswire. Learning later that my Agency had knowingly withheld knowledge that the downing of the airliner was an unintentional error that we presented to the world as a deliberate act by The Evil Empire contributed to my disillusionment with the Agency.

As Cultural Attaché, I was ex officio the Treasurer of the Fulbright Commission and had to sign off on all expenses. I discovered that my boss, the Public Affairs Officer and his predecessors padded their entertainment expense accounts by making grants to the Commission, which would then pay for their parties. This laundry operation was a clear violation of regulations and the intent of Congress.

I reported it to the security officer, the ambassador and the deputy chief of mission with no results, except to be removed as Treasurer by the ambassador. I used the USIA inspector’s hot line. The investigators’ report determined that everything I had said was true. Obviously this did not win me any friends among the higher echelons of USIA. My time was up, and I wanted to leave anyway with full retirement at age 50.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS

Education

Pomona College, 1959–1963

Peace Corps–Ivory Coast, 1964–1966

Joined the Foreign Service 1967

Washington, D.C.—Assistant Science Advisor 1970–1974

Paris, France—Press Attaché 1977–1981

Geneva, Switzerland—Counselor for Public Affairs 1984–1988

Paris, France—Cultural Attaché 1988–1992