Elizabeth Jones became the U.S. Ambassador to Kazakhstan in 1995. On July 3, 1988 an Iran Air flight was making its way to Dubai from Tehran. However, the plane never reached its destination. It was struck down, and the repercussions of this accident lasted through the years of Jones’ Ambassadorial assignment.

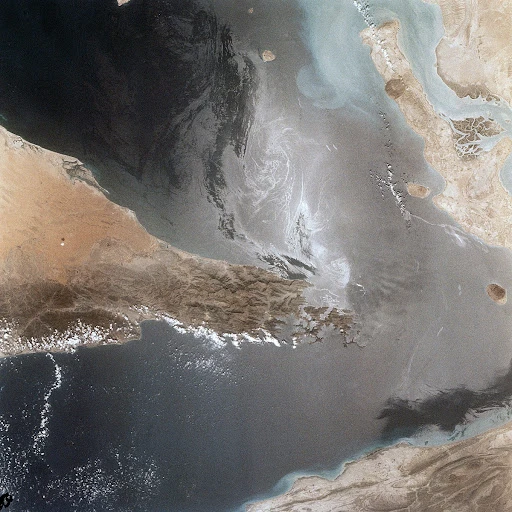

In 1988, a war between Iraq and Iran had been raging for approximately eight years. Located off the Persian Gulf is the Strait of Hormuz. A US helicopter began to retreat after receiving warning fire from the Iranians over their territorial waters. As a means of giving support to the fleeing helicopter, the USS Vincennes pulled into the strait. In the meantime, an Iran Air Airbus A300 was flying over the strait, taking its usual route to Dubai. The US Navy fired a missile, shooting down the passenger aircraft and killing the 274 passengers and 16 crew members on board. US officials claimed the action was in self-defense because they mistook it for an Iranian military plane. The United States also claimed it tried to contact the aircraft over ten times and received no response. However, this claim is disputed by the Iranians. They said the U.S. conducted this attack in pure negligence and knew that there was a civilian aircraft signal. While the truth remains unclear, the United States and the vessel’s captain received heavy criticism for the act. Furthermore, the consequences of this mistake would persist years later in negotiations with the Iranian government.

In 1998, when Jones was nearing the end of her assignment in Kazakhstan, the United States and Europe were trying to negotiate a deal with Iran on nuclear weapons. Based on the reporting and intelligence the United States possessed, Iran did not have a fully developed and operational nuclear weapons program. However, the U.S. believed that a nuclear weapons program was in the developing stages. Iran was also supporting international terrorism and politically undermining the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. The U.S. did not want to deal with Iran as long as it was pursuing these policies. But at the same time, the U.S. wanted to open a dialogue with the Iranians to try to convince them to stop further development of their nuclear program.

Due to the political climate at the time, all US government communications with Tehran went through the Swiss. However, that did not make a difference since the Iranian government was mostly unresponsive to any US attempts to communicate. The Iranians were unwilling to have a conversation because they were upset over a number of issues, one of the biggest being the strike down of the civilian aircraft from ten years prior. In an attempt to open a conversation with the Iranians, Elizabeth Jones worked with a team of people to write a speech that would be delivered by Secretary Madeleine Albright. While the U.S. provided compensation to the families of those killed on the Airbus A300, a formal apology had yet to be released. In this speech an apology for the accident was to be included, along with an apology for mishandling one of their elections and an offer to lift sanctions. Though Jones did her best in negotiations with the Trade Representative, the proposal to lift sanctions included only agricultural goods and handicrafts. In the end, the speech was received with silence from Tehran.

In this “Moment in U.S. Diplomatic History,” we get a glimpse of US relations with Iran during the Clinton administration from the perspective of a career ambassador. Elizabeth Jones had a fascinating and distinguished career in the Foreign Service. She served in Kazakhstan, Bonn, Islamabad, Kabul, Cairo, Amman, Baghdad, and Berlin. With deep experience in the Middle East, it is during her time in Kazakhstan where she worked diligently to open up dialogue with the Iranians.

The second part of Elizabeth Jones’ interview was conducted by Charles Stuart Kennedy on April 26th, 2005.

Read part II of Elizabeth Jones’ oral history HERE

Read parts I and IIII of Jones’ history HERE and HERE.

Drafted by Kaitlyn Flynn

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

That was the bottom line. It was just too hard. Their politics would not permit them to open a discussion with the U.S.

The Consequences of America’s Mistake in a Crucial Negotiation Period:

JONES: Iran, also very interesting. The effort that we had with Iran at the time was of course we absolutely refused to deal with it so long as it had policies to undercut the Israeli-Palestinian peace process, continued to develop a nuclear weapons program, and supported international terrorism.

At the same time, we wanted to demonstrate that there was a way out of the box and we were constantly saying to the Iranians, “We’re happy to talk to you about all of these issues.

You don’t have to do these things before we have a conversation. You just can’t take any of these issues off the table for the conversation.” And the interesting thing to me was, we communicated all this through the Swiss, who were our protecting power in Tehran. But, the Iranians really couldn’t take the step to open discussions with us, because for them, that was a concession, that was a loss of face in a way that was kind of interesting.

We tried to find a way to make it easier for them to have a conversation with us. This was when there was clearly a divide or a discussion in Iran between the hardliners and the not so hard liners, to the point that there was an election. Rafsanjani came in, and there seemed to be quite a bit of democracy in Iran, to the point that I would call Iran one of the more democratic countries in all of NEA[the Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs], in terms of actually honoring the results of an election. I had my Iran desk officer do a really careful study of all of the issues that were the irritants in the Iranian-U.S. relationship, as far as the Iranians were concerned, what was it that upset them the most, to try to see if we could speak to all of those issues in a way that would put them aside enough so that they would feel that a conversation with the U.S. was not a loss of face.

He did that; he did a great job. We proposed a policy to the Secretary, to which she agreed, which was that we would try to come up with a set of ideas that she would approve. We would work interagency, we would then put into a speech, a big speech. We did all of that and we came up with several ideas in which we tried to speak to the irritants, the big irritants in the relationship.

The irritants were: serious upset about the U.S. shootdown of the Iranian commercial airliner over the Gulf; serious upset about Mossadegh being thrown out by the U.S. and the Shah being put back in; serious upset about the Shah being admitted to the United States when Khomeini threw him out when he had cancer; and serious upset about the sanctions, the continuing sanctions against import and export of goods. We got fairly far in the interagency process in the language we could use. We got very close, virtually apologizing for shooting down that plane.

Q: It was a horrible mistake. We did it!

JONES: We had already offered compensation, which they’d accepted, for the families. So that part was already done. But the kind of apology that they were looking for, we hadn’t really come up with. We came up with language for an apology that was the most I could get and it was an apology. We came up with a discussion of the history of the Mossadegh coup that concluded that we should have honored the elections, so an acknowledgement that we’d mishandled that, basically.

And on lifting the sanctions, or removing the sanctions, the closest I could get was removing some sanctions, on agricultural products and handicrafts, basically. That was the toughest, because of the U.S. Trade Representative language on this kind of thing means all kinds of things to trade specialists. So they finally agreed we could lift sanctions on Iranian exports to the United States of agricultural goods and handicrafts, which translated into pistachios and rugs, unfortunately, but you take what you can get.

We put it all together, had Secretary Albright make a speech in Washington. It turned out that the speech was on March 17, 2000. We had done a lot of work ahead of time to position the speech with the Hill. I had done a million briefings with staff on the Hill so that they would know what was coming, why we were doing it, that this wasn’t a sign of weakness, this was how we were going to get the Iranians to finally do the three things we needed them to do. We did a huge rollout of it with our European friends and allies.

We had briefed the Swiss, they had gone into the Iranians to say, “The Secretary’s making this speech. This is what it means. This is what we’re looking for,” et cetera. So we really, really made a big, huge diplomatic effort. There isn’t anything that I thought of later that I wished I’d done to roll this out, to try to get them to understand that this was a major, major policy initiative.

Dead silence was the result, dead silence. We got pretty good press in the U.S., an acknowledgement that this was a serious effort by the Clinton Administration to open a new chapter with the Iranians.

From Tehran, we only got an acknowledgement that, “Yes, thank you, we’ve read the speech” and we kept going back to the Swiss to say, “What’s the deal?” Finally, a month later, the Swiss ambassador, presumably, was called in and they said, “Please thank the Americans for the speech. We understand what the intention was. We can’t deal with it.”

That was the bottom line. It was just too hard. Their politics would not permit them to open a discussion with the U.S.

Q: Were you getting either any good analysis from outside or intelligence from inside about the inner workings? You had this elected government and then you had this ayatollah committee, which apparently had final approval.

JONES: That’s right and we were getting a substantial amount. We knew going into it that it would be a fight between the “reformers” and the conservatives, that was the terminology used. I was in touch on a regular basis with the Canadian ambassador who was there, with the Swiss ambassador. The Canadians would regularly come down to see me. I’d go up to Ottawa to see them.

We would have EU quad meetings quarterly to talk about Iran, just to make sure I understood. They would get their various ambassadors to come out of Tehran to meet with me about what was going on there and their take on it.

So we had a pretty good sense of it and we’d briefed all of them ahead of time on the intent of Secretary Albright’s speech and we said, “Could this work?”

They all said, “It could work, but there will be a fight.”

To me it really reminded me of the way the fights go in Washington. Yes, there could be a fabulous initiative somewhere, but you might not be able to get the neocons and the more liberals to agree on responding to it, like on North Korea, say, or whatever.

So we just never got anywhere with it, which was really a shame. But, we went ahead and lifted the sanctions like we said we would, none of this was contingent on an Iranian response, we just said, “We are changing the rules to allow” these kinds of exports.

JONES: They were very unhappy. It was “appeasement,” it was “What are we going to get for it?” It was very negative, but they couldn’t stop us, they just weren’t strong enough. It turned out that the positive arguments for making the effort, for giving it a good try, won out, in the Congress and elsewhere.

They could have stopped us. They didn’t have to agree. If I had had a complete stonewall on lifting those sanctions I wouldn’t have gone ahead with it, I couldn’t have. USTR wouldn’t have let me. It didn’t require legislation. It did require an executive decision and we got it, we got that.

Table of Contents Highlights:

Ambassador to Kazakhstan, 1995–1998

Washington, DC—Special Advisor for Caspian Energy Diplomacy 2000–2001

Washington, DC—Assistant Secretary for European and Eurasian Affairs 2001–2005