“I traveled in a long convoy, with armed body-guards. Much of the concern for our safety stemmed from the assassination of Ambassador Frank Meloy who had been killed about five years previously by the PFLP.” This is how Ambassador Robert S. Dillon described his daily life as the U.S. Ambassador to Lebanon during the peak of the Lebanese Civil War. Dillon was appointed as the ambassador to Lebanon after the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) had kidnapped and assassinated his predecessor, Ambassador Francis E. Meloy, Jr.

The Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990) involved various factions, including Christian Maronites, who were cooperating with Israel, the Druze, Sunni Muslims, Shia Muslims, and the Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. During the summer of 1982, Israel invaded Lebanon to create a buffer zone north of Israel. This invasion became known as the First Lebanon War, or Operation Peace for Galilee by the Israelis. The Israeli military, Israel Defense Forces (IDF), clashed with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and caused a great number of civilian casualties on both sides. The Israeli government claimed it had reason to invade and attack the PLO because the group assassinated its ambassador to the United Kingdom. This claim was false, as the crime was committed by the Abu Nidal Organization (ANO). While the core members of ANO used to be a part of the PLO, they had fractured from the PLO approximately eight years before the assassination. The ANO was a known enemy of the PLO, which only made the claim by the Israeli government more ludicrous.

The IDF collaborated with their puppet government, the Free Lebanon State and Maronites to attack the PLO, Syrians, Muslim Lebanese, and leftist forces. After the assassination in Lebanon of President Bachir Gemayel, the Israel-backed leader, peace between the groups grew increasingly unlikely. After the Israeli hold on Beirut became too difficult to defend, positive public opinion of the war in Israel dramatically decreased. Following the massacre of Palestinians and Shias, the IDF finally retreated to Southern Lebanon. This was an area steadily held by the Free Lebanon State. However, the War of the Camps broke out in 1984. This was a six-year conflict between the Lebanese factions that fought together against the Israelis. Syrians battled first against the remaining PLO forces and eventually the Israelis. By 1990, Syria established complete control in the region. However, Israeli forces did not fully withdraw from Lebanon until 2000. Lastly, the Syrians who came into Lebanon occupied the country until 2005.

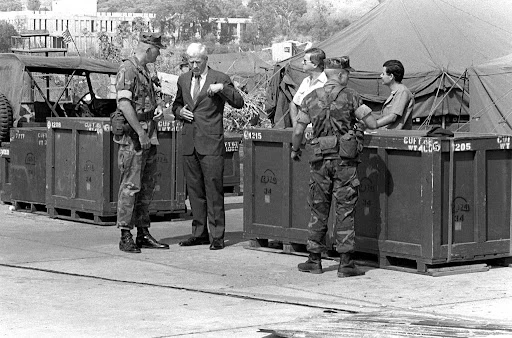

This “Moment in U.S. Diplomatic History” provides insight on the June 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon. Ambassador Dillon experienced the Israeli invasion and survived the bombing of the U.S. Embassy in Beirut. Ambassador Dillon dealt with all factions, including the fifteen Christian sects and three Muslims groups in the country. He lived in the eastern side of the Lebanese capital, Beirut, which had been split into eastern Beirut and western Beirut, with a line of demarcation called “The Green Line.” The line separated the mainly Muslim factions in predominantly Muslim West Beirut from the predominantly Christian East Beirut controlled by the Lebanese Front. Dillon departed Lebanon on October 11, 1983—eleven days before a truck filled with explosives drove into buildings that housed American and French service members of the Multinational Force in Lebanon (MNF), a military peacekeeping operation during the Lebanese Civil War. The attack killed 242 Marines and 58 French military personnel.

Robert Dillon’s interview was conducted by Charles Kennedy on May 17, 1990.

Read Robert Dillon’s full oral history HERE.

Drafted by Hani Zaitoun

Edited by Kaitlyn Flynn

ADST relies on the generous support of our members and readers like you. Please support our efforts to continue capturing, preserving, and sharing the experiences of America’s diplomats.

Excerpts:

Some hours later, the Israelis announced that they were moving into Beirut to “restore order.” There was no disorder. People were stunned; the Muslims were extremely apprehensive because they were afraid that the assassination would open them to massacres.

The Israelis in Lebanon:

Q: The invasion occurred on June 6, 1982. Were you just waiting for the “shoe to drop” at this point?

DILLON: Yes. The Israelis invaded and immediately announced that they would “drive the Palestinian artillery back from the border” where it was a threat to Israel. This rang false with us because we didn’t really believe that there was artillery in southern Lebanon although we couldn’t be certain… In the midst of this, we were sitting in Beirut and reporting what we could see. It became clear to us that a full scale invasion was taking place.

I thought that Beirut was the objective, even though the Israelis were still claiming that they were interested only in the 40 kilometers north of their borders.

Q: What did you think the Israelis were trying to accomplish?

DILLON: They were trying to kill as many PLO as possible. They spent a lot of time trying to kill Arafat, the head of the PLO. They had agents in the city and whenever they had Arafat spotted, whether there was a cease-fire or not, they would zero in on him. Several times, they would initiate air-strikes on apartment buildings that he just left. Arafat moved from place to place throughout this time. In the meantime, we, the Americans, were the go-between trying to negotiate a cease-fire and an evacuation. Habib handled most of that. The interlocutor with the Palestinians, in most cases, was Wazan, who was the Prime Minister and a Sunni. Habib, assisted by Morris Draper, went back and forth to arrange the cease-fire and the evacuation. He did a magnificent job; he was good. He got a fairly good agreement, but there were problems left. Where would the PLO go, which was a perfect illustration of the Palestinian problem because they have no place to go. The PLO agreed to evacuate if we could find some place for them to go. Of course, every Arab government said “No, we won’t take them.” There were 13-17,000 PLO fighters. The U.S. put massive pressure on the Tunisians, who finally agreed to take the bulk of the fighters. Then others agreed to take a few. Syria took some; Jordan took some; Sudan took some. So a cease-fire was arranged….

Q: What were you doing as the PLO fighters pulled out?

DILLON: The Israelis were all around Beirut and had been creeping into the city. There was no American Embassy at the time in the city. The Embassy in effect was in my house. By this time, the house was behind Israeli lines. There were Israeli artillery positions almost beside the house as I mentioned earlier. The Lebanese forces—the Maronite militia—was in the area but had declined to join in the fighting. The Israelis were very disappointed by this policy because they thought they had a commitment from the Lebanese Forces. They apparently had some covert cooperation, but no overt action

Bashir Gemayel had just been elected President. The population of Beirut had been reduced to about half a million, most of them Lebanese, but including a fairly good number of Palestinians.

Once the PLO fighters had been evacuated, the Israelis were to be in static positions, but there was no opposition to them except the multi-national forces which were thinly spread around Beirut in defensive positions. When Bashir Gemayel was elected president, even though some people considered him a “thug” and a fighter, many of us thought he was a good choice. He was 34 years old. He had certainly developed a great deal of sophistication over the previous year or so. He had progressed from being a fighter to a fairly astute politician. As I have mentioned, he had covert relations with the Israelis, which was an anathema to other Lebanese. On the other hand, he had a vision of Lebanon which included Muslims, unlike many Maronites who did not see such a multi-religious community. He recognized the necessity of dealing with the Shiites and was elected with a good deal of support from that community. He didn’t get any support, nor did he seek it, from the old line Sunni Muslim leadership which was the traditional leadership that the Maronites and American administrations had always dealt with.

In Beirut, there was a vacuum; only local police were patrolling the streets. No armies or militias were in the city. A very few days after the evacuation of PLO forces, Bashir went to a Phalange Party meeting in Ashrafiyah, which was its stronghold. The Phalange was the right-wing party led by Bashir’s father. In effect, what Bashir was doing was having a series of victory celebrations and was using them with some skill, not simply to gloat on the victory, but to prepare for what had to be done after the victory—repair ties, reassure people who might not have been enthusiastic that he would be cooperative and so on. The Phalange by this time had come to understand that their name was an unfortunate one stemming from Franco’s fascist regime in Spain. It understood that to Western reporters the word “Phalange” had a bad connotation. So they simply called themselves Kataeb, which simply meant “the organization” and that is how we in the Embassy referred to them.

Kataeb headquarters was in an apartment in Ashrafiyah, which was in East Beirut. Since all the Muslims had been expelled from that area, there were only Christians in that neighborhood, mostly Maronites. The apartment house in addition to holding offices had also people living in it. One of the families that lived there was the Shartouni family who were Greek-Orthodox. As we later found out, some members of that family had been involved with groups that favored the union of Lebanon and Syria.

As I mentioned before, people who subscribed to this policy were mainly Greek-Orthodox, although undoubtedly there were members of other faiths who believed in a “greater” Syria. Bashir’s murder was caused by a large bomb being placed in the apartment above the Phalange headquarters which was occupied by the Shartouni family. When the bomb went off, a number of people were killed. A number of hours passed before it was established that Bashir had been among the dead. In the meantime, there were many rumors that he was still alive, although within a couple of hours we were certain that he had been assassinated….

So now Bashir is dead. Some hours later, the Israelis announced that they were moving into Beirut to “restore order.” There was no disorder. People were stunned; the Muslims were extremely apprehensive because they were afraid that the assassination would open them to massacres. The Israelis moved in, over our objections, and took over the entire city. Subsequently some Muslims professed to believe that Bashir had been killed by the Israelis because he had made it clear that he would not front for them. He had had a stormy meeting with Begin during which he had made it clear that he intended to be the President of all of Lebanon. As far as we know, the Israelis did not kill Bashir, but I would guess that they were looking for a pretext to occupy Beirut because they believed that “enemies” lived there and they wanted to get them. The Israelis are big on “enemies.” They did over-run Beirut and killed some people in the process. I don’t know who those people were or why they were killed.

The Syrians in Lebanon:

Q: How did you view the Syrians in this period?

DILLON: The Syrians loomed very large in our eyes. The Syrian activities in Lebanon were aimed mainly at bolstering their position. The Syrians were in Beirut; they were on the road between Beirut and Chtoura; they were in the Bekaa Valley. They were not in southern Lebanon where the Israelis had declared a “red line” that the Syrians respected….Syrian policy in Lebanon had a certain logic, at least from their point of view. They had never accepted the break up of greater Syria.

They believed that Lebanon really belonged to greater Syria. They also believed that the Christian militia, if left alone, would play an Israeli game and that the Syrian presence in Lebanon was to guard against such a turn of events. At the same time, they had a deep concern about uncontrolled Palestinian forces in Lebanon or indeed anywhere else in the area because they had the potential to start a major conflagration. That led the Syrians to wish to control PLO forces, which of course gave rise to very poor relations with the Palestinians.

TABLE OF CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS:

Education

Washington and Lee University, Duke University

Entered Foreign Service in 1955

Ankara, Turkey—Political Officer 1962–1966

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia—Deputy Chief of Mission 1974–1977

Cairo, Egypt—Deputy Chief of Mission 1980–1981

Beirut, Lebanon—Ambassador 1981–1983

Vienna, Austria—Deputy UNRWA Commissioner General 1984–1988