Saving American WWII codebooks from the Japanese special police

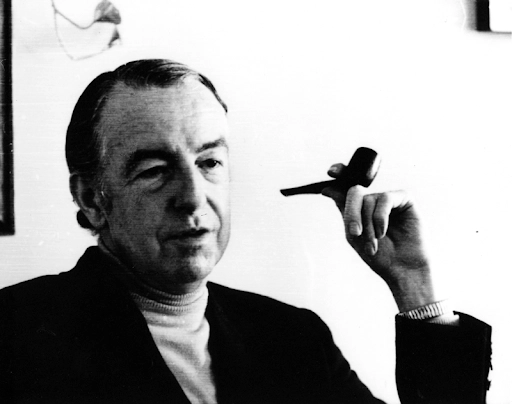

In late 1941, Vice Consul and Massachusetts native Niles W. Bond spent most days reporting to the Navy Department on Japanese ship movements in Tokyo Bay, which he observed through a telescope on the roof of the U.S. Consulate in Yokohama. When he heard radio reports of Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, he knew it was only a matter of time before Japan’s secret police, the Kempetai, would arrive to take over the Consulate.

It was 5:30 a.m., and Bond woke up the only other vice consul at post. “We had some things to burn,” Bond later recalled. But the Consul General had insisted that the vice consuls burn files first and save the code books for last, “because we may get a coded message from the Embassy that we will have to be able to read.” When the Kempetai arrived a few hours later, the code books were still intact.

Here’s how Bond described the scene:

“The truckload of Kempeitai guards were commanded by a major. He made us go around and open all the files and show him what was inside. He saw the code books. They were in a vault in the consul general’s office, but he didn’t touch them. He didn’t touch anything. He just closed them up and put a Kempeitai seal on them…. This was a mistake on his part, because my vice consul colleague, Jules Goetzman, and I decided that the thing at the top of our list was getting those code books back, out of the vault, and destroyed, before the Japanese got them and read them or used them.”

Confined to their upstairs apartments, Bond and Goetzman snuck downstairs late at night and back into the consul general’s office, with Kempeitai guards sleeping in the next room. Working by the light of matches, they broke the seal and carefully opened the safe, cringing with each knock of the tumblers. They recovered the codebooks and were soon back upstairs burning them in their fireplace.

The guards woke them roughly the next morning and took them downstairs to see the major. Bond continued: “The major took us into the consul general’s office, pointed to the broken seal on the safe, and asked if we knew anything about it. When we nodded, the major ordered us to open the safe.…He saw the empty space where the code books had been [and] demanded that the books be returned to him at once. My colleague replied that they had already been destroyed and offered to show the major the ashes. The major, in a rage probably fueled as much by fear for his own head as anything, drew his sword and demanded an explanation.

“Recalling a discussion we had had the night before while burning the code books, Goetzman and I, in an inelegant mixture of English and Japanese, endeavored to explain the destruction of the codes in terms of “bushido,” the traditional samurai code of loyalty and honor. We pointed out that Americans, too, had such a code of conduct and tradition of loyalty, which demanded that we risk our lives to protect our country, in this case by protecting its codes.

“My colleague then asked the major what he would have done in the same situation. The major slowly sheathed his sword, drew himself to attention, and then quietly began to weep as he left the room. From that moment on, nothing more was heard from the Japanese about the incident – or about the major, whom we never saw again. But the books were burned, and I was told when I got back to Washington that they were still uncompromised at the time we destroyed them.”