“The Government of the United States of America acknowledges the Chinese position that there is but one China and Taiwan is part of China.” With this Second Joint Communiqué of the U.S. and China, issued on January 1, 1979, the Carter Administration no longer recognized Taiwan as a sovereign state, but rather preserved the “cultural, commercial, and other unofficial relations with the people of Taiwan.” The U.S. embassy there was abolished and its place the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT) was established. The change in U.S. position led to massive protests in the streets of Taipei when it was first announced on December 15, 1978. At right is the symbol of National Day in Taiwan, the Double Ten (for October 10, 1911 and the fall of the Qing Dynasty.)

After Mao Zedong defeated Chiang Kai-Shek’s Kuomintang in 1949, the United States refused to recognize the People’s Republic of China, but rather continued to support Chiang’s Nationalist Chinese government on the island of Taiwan. By 1972, President Richard Nixon made his historic trip to Beijing, in a bid to play the “China card,” i.e., using closer ties with China to gain more leverage over the Soviets, and to tap the huge Chinese market. The PRC, for its part, was also looking for allies, as relations with its former ally, Vietnam, were now severely strained. Carter’s announcement angered many in Congress, which then passed the Taiwan Relations Act giving Taiwan nearly the same status as any other nation recognized by the United States, mandating that arms sales continue, and establishing the AIT.

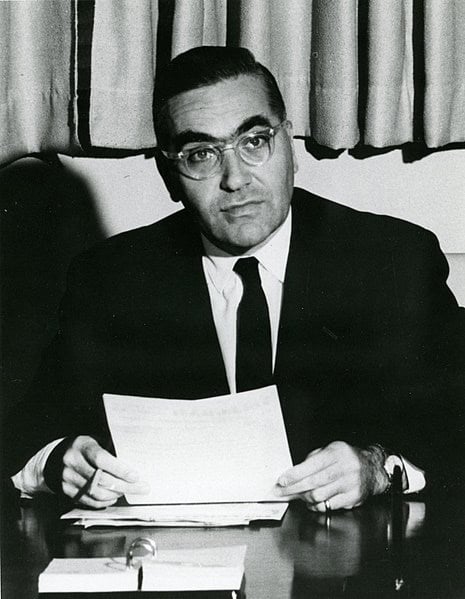

Neal Donnelly was Public Affairs Officer in Taiwan at the time and tells of the anger he experienced first hand, including the press conference in which the Vice Foreign Minister excoriated the U.S. in front of Secretary of State Christopher, the volatile demonstration against the U.S. motorcade, as well as how AIT and the Taiwan came to a détente of sorts, dirty jokes and all. He was interviewed by David Reuther in 2001.

“Stand by for an important cable”

DONNELLY: [The announcement] was a shock, I think for everybody. There had been indications that we were going to do something like this. In September of that year, we were still in the embassy of course, and the country team, that is the heads of the sections, was called together to discuss how we would operate if this happened. Then we put all in of our ideas…sent [them] to Washington as if Washington was at all interested in our opinion, which they weren’t. (laughs)…

My recollection of that day that the announcement was made, that was, I guess, the 15th [of December] in Washington; the 16th in Taiwan. That morning a cable came in to the Ambassador and probably only the Ambassador and the political officers were aware of the contents of that message. But that message was something like, “Stand by for an important cable.” It didn’t say what.

That night, Ambassador Leonard Unger went to the American Chamber of Commerce Christmas party at the Officer’s Club on Chung Shan North Road. He had on his tuxedo and a red bow tie, as I recall….A cable came in late at night, I’m not sure if it was 9:30 or 10:00 at night — something like that — saying that Carter was going to announce the normalization of China and the de-recognition of Taiwan. Mark immediately got a hold of Unger at the Christmas party at I think about 11:00 pm and then Unger started the wheels in motion to contact Chiang Ching-kuo who was the President of the country.

Now you don’t just go to the President of the country’s house and ring the bell and talk to him, so it took a while to go through the several people that they had to and then they got Chiang Ching-kuo at, I think, slightly after two o’clock in the morning. Unger told him that we were de-recognizing Taiwan.

I’m told that he was in shock, shocked into inaction, and really didn’t do anything until the following morning. At six o’clock in the morning I was called by the duty officer and told to get down to the office. I got there, I guess about 8:00, and the country team was in the bubble [secure meeting room]….

We got there and Unger, still in his tuxedo and red bow tie, told us what Carter was going to do and we should call our families and tell them to listen to the radio, the armed forces radio station in Taiwan which would broadcast the message. And to tell our families to keep the kids home from school and things like that. So we did.

Then the announcement came and, of course, people were very upset. One of the first things that President Chiang Ching-kuo did was to cancel the election. He’d just been shocked into inaction because he wasn’t expecting it.

Our office had about half mainland Chinese and half Taiwanese Chinese. The majority, of course, felt betrayed and they felt very bad, but there was a minority of Taiwanese, maybe four or five, who thought it was a good idea. They thought it was a good idea because of the dislike of the Kuomintang government and they thought this may, somehow, give Taiwan a chance to become independent. So there were a few who thought it was a pretty good idea. The election was cancelled and we got a few weeks of just sort of fumbling around.

Of course there was a reaction in the United States, as well. The reaction was that not enough people were told; I don’t think Barry Goldwater knew. Had Barry Goldwater known, he would’ve somehow thrown a monkey wrench into it if he could. He and most other conservative Republicans were kept out of it. There was also a feeling that Carter was a little petty about it by announcing it at 9:00 at night Washington time during prime time which meant that as soon as he announced it, people like Goldwater wouldn’t have any time to mobilize anything and it wouldn’t give the people in Taiwan any time either. In any event, we were sort of fumbling around. It was decided in Washington that it would probably be a decent thing to do to send a delegation to Taiwan to smooth ruffled feathers.

A Very Awkward Press Conference

So, [Secretary of State] Warren Christopher led a delegation with [State Department official] Roger Sullivan and a lot of other people….

They arrived at the airport. I was the head of USIS [U.S. Information Service], but I was also handling all of the press relations. Before they came, someone in the government information office talked to me. I went over and they wanted to know if Christopher would give a press conference….

He said, “As a courtesy, would you let [Vice Foreign Minister] Chen Fu,” (that’s Frederick Chen) “introduce him?” I said, “That’s a little unusual. I’ll ask Ambassador Unger.” At this point, when we were trying to bend over backwards to smooth their feathers, Ambassador Unger agreed….

We got into the airport and as we were going into the airport, we noticed that a lot of students were milling around. Now that airport at that time had a military side and a civilian side, but the same runway, of course.…We were told before, that we probably should use Chinese government cars instead of our own cars in the motorcade. We thought this strange, but who’s ever in charge of automobiles said okay. So in the motorcade were, I suppose, thirty cars or so; half the Chinese delegation, half the American, and they lined up outside.

Christopher came with a delegation, Roger Sullivan and other people, and he was led into where the press were. A very small room, but there were about forty or fifty press….In any event, he arrives and I would’ve introduced him if everybody agreed and I would’ve said, “Ladies and gentlemen, this is Warren Christopher, the Deputy Secretary of State. He would be happy to take your questions.” That’s all…

Fred Chen’s introduction was not “Ladies and gentlemen of the press, this is the Deputy Secretary of State. He has a short statement and then he’ll take your questions.” It was nothing like that at all. It was a condemnation of the act of normalization, and the Taiwan government negotiating position on normalization, from which they would not retreat. We were talking about people-to-people relations and they wanted government-to-government relations, and they would not budge from that. The introduction was very hard-line, very long.

It went on for about five minutes, after which, Warren Christopher read this very bland statement …. [in which he said he was] “look[ing] forward to meetings which will reflect the goodwill and understanding that has existed between us.”

Obviously there wasn’t any goodwill or understanding. (laughs) …

“We had to abandon our car because it was so badly damaged”

We went out then and got in the motorcade and started out. By the time that we got outside the gates, the students, I don’t know how many there were, several thousand, surrounded the cars and began to pelt them with eggs and rocks and to jump up on top of the cars and stamp on the roofs.…A student came with a flag pole and shoved it through the window and broke the window. I was covered with glass and cut a little bit. Ambassador Unger was driving with one of the admirals, I think. He was mildly cut and his glasses were knocked off. He had the Seventh Fleet commander with him, I think….

Our car was badly damaged. They kept us for a long, long time in that motorcade; wouldn’t let us go through. Just pounded the cars and breaking the windows. No one was hurt badly and I’m told by a young friend of mine who was a military officer — a young Chinese friend — that the soldiers were told to don civilian clothes and make sure that none of the students got too wild. He said he himself wrestled down a student who was going after the Ambassador’s car with a hammer. So they were prepared.

The demonstration was supposed to be spontaneous, but when we came to the gate that night I noticed that there was a large truck and on the side of the truck was written in Chinese, “Lu Tung Tzu Shuo” which means “mobile toilet,” and you very seldom have mobile toilets at spontaneous demonstrations. Also, I know from a friend of mine who was a student at National Taiwan University, that there were loud speaker announcements that morning at that university and others, urging students to go and rally at the airport. So it was a put-up job.

We finally broke out of the cordon that the students had created, but had to abandon our car because it was so badly damaged. When the cars broke out, they sort of went in all different directions. Some went to the Grand Hotel and our car went up to Yang Ming Shan, up to the Kuomintang resort up there. I forget the name of it. There were three or four cars that went off in one direction and Roger Sullivan was in one of them. Then other cars just went to places like U.S. Military Headquarters….

[Our car] was a Chinese government car. It seems that they thought they didn’t want to damage our cars and have to pay for them. (laughs…) First we went to the U.S. Army Headquarters and then got on the phone there with Washington….Some of the people were asking what we should do….I do remember that there were a couple in the U.S. delegation that wanted to turn right around, get back on those planes and fly out of there. The reason they didn’t is because there’s a U.S. Air Force regulation, I’m told, that a pilot has to have so many hours sleep after so many hours in the air….

A Not-so Dignified Flag Ceremony

We de-recognized formally on January 1st, but December 31st, the flag came down for the last time and that was obviously a news event. Ambassador Unger wanted the flag to come down with dignity and had a private, sort of family affair. I argued that that was a mistake. I argued that the U.S. press and the U.S. people would want to see this and it should not be kept from the press. He overruled me, of course. So that day, I went down to the embassy and told the Ambassador, “Make sure, if you don’t want anybody in here, that that gate is shut.”

They were going to take the flag down, I think at sundown, if I recall. What Unger wanted is he was going to stand there at the foot of the flag, have the Marines take down the flag, fold it in military manner and give it to him in a very dignified way. That was going to be alright, but a very enterprising American reporter…got a hold of a Chinese government car somehow and came to the gate and tooted the horn and the embassy gate guard, a Chinese, opened the gate and let him in.

Now we’ve got, I think he was one of the news networks, CBS maybe, an American newsman inside the gate. Well, Unger was livid and the security officer was running around screaming, especially at me. I said, “I didn’t open the gate.”

They said, “You’ve got to get him out of here,” and I said, “What do you want me to do, throw him out? He’s bigger than I am.”

They said, “Tell him to leave,” and Unger at this point, he’s going to call the head of NBC or CBS, whatever it was, and I said, “You’re going to get no place. It’s the middle of the night, and if you tell him, ‘One of your reporters was enterprising enough to get in here’, he’ll probably get a raise.” So Unger finally cooled down, but he was mad as hell.

They said, “Get him out of here,” and I said, “I’ll tell you what, I will go down and ask him to leave.” That’s ridiculous, but I said I’d do it….I said, “What if I asked you to leave?” (laughs) He said he’d tell me to go to hell. I said, “Okay, I asked you and that’s your answer.”

So Unger then decided that he would have the flag taken down, folded, and brought into him and presented to him inside the embassy. I said, “Well, you know, they’re going to get pictures anyway. There’s this overpass right by and there are apartment buildings all around and the newsmen and all around. Just let them in,” but of course he wouldn’t do it. I have some pictures….

Well, the flag is down and now we formally recognize China, but we’re still in Taiwan for two months at which point someone from the State Department comes out…to tell us what our future is going to be. Now we had all these ideas that if we became non-State and civilians, we’d all get civilian pay and all of this sort of stuff (laughs)….

A Dirty Joke About De-recognition

Q: Well, here you are, it’s the first days of AIT, you’re not getting paid, there’s no law that covers you, you literally can’t talk to your colleagues officially. I wonder who pays for the telephone calls back to Washington (laughs) (…). And who comes out to be the head of AIT?

DONNELLY: …I was made acting Director of AIT. A friend of mine quipped that the highest rank I got was acting director of an unofficial entity….

Dare I tell a joke on this tape?

Q: Oh, please.

DONNELLY: This joke was told to me by a Chinese reporter…during the Christopher mission…. The joke has to be told in Chinese, that Fred Chen’s or somebody’s driver was driving an American and a Chinese official around and they kept arguing in English about people-to-people or government-to-government [contacts], and the Chinese driver didn’t speak any English.

So at the end of the day he asked his boss…,“I don’t understand. You two talked all day long about ‘P’i Ku Tu P’i Ku’ (people to people) and ‘Kan Men Tui Kan Men’ (government to government), what’s the difference?” Of course, P’i Ku means “ass” and Kan Men means “rectum.” It was a joke that made the rounds during de-recognition. So it shows that the Chinese have a good sense of humor….

After we opened up shop again and started sending [press] backgrounders, I was called over to the Government Information Office. Carter gave a speech in which he said something about the People’s Republic of China. Now, in Taiwan…you can call them “bandit Communists” or “Chinese Communists,” but you can’t call them the People’s Republic of China and I was told that I couldn’t send this out; I’d have to correct it.

Of course now I’m not official. I said, “I’m not going to correct my President’s language. You know, I’m not going to do it. You can do what you want, but I’m not going to do it. You can throw me off the island; whatever you want.”

They backed down, but they thought they could intimidate the U.S. government….The Taiwan government realized pretty soon that their best course was to get along with us rather than to frustrate us.