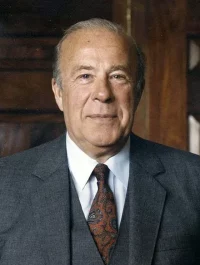

George P. Shultz was Secretary of State for President Reagan from 1982 to 1989, the longest such tenure since Dean Rusk in the 1960s. As Secretary, Shultz resolved the pipeline sanctions problem between Western Germany and the Soviet Union, worked to maintain allied unity amid anti-nuclear demonstrations in 1983, persuaded President Reagan to dialogue with Mikhail Gorbachev and negotiated an agreement between Israel and Lebanon in response to the Lebanese civil war. After leaving office in 1989, Shultz worked closely with the Bush administration on foreign policy and was an adviser for George W. Bush’s 2000 presidential campaign.

Shultz was a no-nonsense manager and highly-prepared negotiator who did not suffer fools gladly, but was compassionate towards those displaced by political upheaval and appreciative of those who served him and the U.S. well. Thanks to his long tenure as Secretary, Shultz touched the lives of many Foreign Service Officers.

All of the following were interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy. Thomas Miller, interviewed in April, 2010, was Vice Consul in Chiang Mai, Thailand from 1979-1981. William Brown, Assistant Secretary, Bureau of East Asia and Pacific Affairs, 1983-1985, spoke to Kennedy in November, 1998. Thomas Niles, interviewed in June, 1998, was Deputy Assistant Secretary of European Affairs at State Department, 1981-1985.

Henry Allen Holmes, Assistant Secretary for Political-Military Affairs, 1985-1989, met with Kennedy in March 1999. Phyllis Oakley was interviewed in March, 2000; she was Deputy Spokesman from 1986-1989. Richard Solomon was on the Policy Planning Staff in State Department from 1986-1989 and interviewed in September, 1996. Charles Anthony Gillespie, interviewed in September, 1995, was Ambassador to Colombia 1985-1988.

Please follow the links to read more about President Reagan, leadership, events involving Secretary Shultz, or to hear the podcast of this Moment. Read about his efforts to create the Foreign Service Institute, which is named in his honor.

Go to Moments in U.S. Diplomatic History

“I want you to put your hand on your country”

Thomas Miller , Vice Consul in Chiang Mai, Thailand from 1979-1981

MILLER: George Shultz, for many of us, was like God. He was a really good guy… He’d have all new ambassadors in to his office, one at a time, as they went out for a five, maybe 10 minute chat.

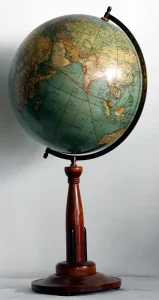

And he’d say, “OK, Mr. Ambassador or Madame Ambassador, you’ve passed all the tests. You’ve been confirmed by the Senate and you’ve passed your security investigation. You’ve done all the things to get the position of ambassador, but you have to pass my test. I have one more for you.” And he’d take them over in the Secretary’s office to where there was this massive globe, and he’d say, “I’m going to spin the globe and I want you to put your hand on your country.”

Shultz would tell this story, and he said, “Every single one of them failed. But I let them go anyway.” Because whenever he spun the globe and he’d say, “I want you to put your hand on your country,” they’d always put their hand on the country that they were going out to. His point was your country is the United States.

“As a humanitarian, Shultz was very interested in refugees”

William Brown, Assistant Secretary, Bureau of East Asia and Pacific Affairs, 1983-1985

BROWN: ASEAN [Association of Southeast Asian Nations] was created in the 1960s while I was in the embassy in Moscow. Remember that when ASEAN was created, it was publically described by its founding members in terms which emphasized that they were not against anybody. They were trying to form a ‘constructive’ grouping to better to raise their standard of living, both individually and collectively. They claimed to have no animus against anyone. It served the interests of the U.S. to go along with that formulation.

It was fascinating to see how someone like Secretary of State George Shultz exhibited remarkable dedication in preparing for and meeting with the ASEAN leaders.…He would constantly ask the economic people within the Department of State, both within the Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs and the Bureau of Economic Affairs, to “recalculate the numbers and reexamine the assumptions.” He was always pushing for clarification of issues, as he had as a former Professor of Economics and a negotiator.

He was constantly asking for more ammunition which would enable him to get the various nations of the world, in this case the members of ASEAN, to open up their markets, introduce transparency, liberalize, reduce internal and intra-zonal protectionism, and, of course, give us greater access to their markets…

I will never forget a visit we had from George Shultz, then our Secretary of State Shultz came through Thailand en route to an ASEAN meeting in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

As a humanitarian, Shultz was very interested in refugees. Encouraged by his Bureau of Refugee Affairs and the refugee organizations in Washington, he wanted to visit the camps. I accompanied Secretary Shultz on helicopter visits to several of the larger camps, as well as Thai military positions near the Thai-Cambodian border. ..

The camp authorities at Phanat Nikhom brought out a variety of refugees, including Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Lao who stood outside a shack built to demonstrate how to use electricity, a toilet, a faucet and a sink with running water. Lined up outside this model structure, in their native dress were lowland Lao, Hmong tribesmen, Cambodians and a few Vietnamese.

Secretary Shultz and I went down the line, with interpreters, to ask how they were doing. There were some grunts from the Hmong tribesmen and a word or two from the Cambodians. When we got down to the Vietnamese, we met a young and very attractive young lady, perhaps 16 years old, wearing one of those long Cao dai costumes. She said in English: “Good afternoon, Mr. Secretary. You are very welcome to Phanat Nikhom. How delighted we are to see you.” And I said to myself: “There’s a winner!”

“He took the bananas and tossed them out on the table”

Thomas Niles, Deputy Assistant Secretary of European Affairs at State Department, 1981-1985

NILES: In the European Bureau, we worked closely with Secretary Shultz to develop ways to encourage more high-level contact between the United States and the European Community in which we could encourage the Europeans to be more positive about themselves.

I know that sounds very strange, but Secretary Shultz was concerned that the Europeans were so pessimistic and so negative about what was going on that they would descend into a slough of despondency and protectionism, which would injure the basic relationship between Europe and the United States…

I recommended to Secretary Shultz that after he finished the December NATO Ministerial, which was always ended at noon on a Friday, he should meet with the [European] Commission at the Ministerial level and talk about US/EC relations. I suggested that he invite his colleagues from Treasury, Commerce, Agriculture and USTR to join him. He agreed, and we started these annual Ministerial level consultations in December 1983…

I remember in particular one incident at the December 1984 meeting. At the end of a pre-meeting lunch among the U.S. participants, Secretary Shultz took some bananas with him. I didn’t understand what this was about.

At the meeting with the European Commission, he took the bananas and tossed them out on the table and said, “Your Ambassador, Roy Denman, Ambassador to the United States,” who was sitting at the table, “recently made a speech in which he accused us of treating Europe like a banana republic because of our policy on steel restraints. That kind of talk is unacceptable among friends!”

This was a big issue at the time – how much European steel could be exported to the United States – and we had a so-called “restraint agreement,” a protectionist method adopted by the United States. The Secretary was very annoyed at Roy Denman, who tended to get under his skin anyway. The Secretary was particularly offended by Denman’s statement that we were treating the European Community as a “banana republic.”

So, he tossed these bananas out on the table. There was shocked silence at the big round table, and the bananas stayed there until the end of the meeting. It was a moment to remember.

“It was a very different management style”

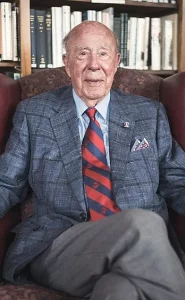

Henry Allen Holmes, Assistant Secretary for Political-Military Affairs, 1985-89

HOLMES: First of all, I saw right away that George Shultz was a really an extraordinary leader in that he combined the best of executive leadership, the ability to handle simultaneously several major portfolios of foreign policy, to keep track of them, to take initiative when the circumstances indicated; and he also was a great leader.

Despite some people’s impression of him because of his public appearance as being the great Buddha, a man who seemed frequently to have sort of a passive expression, George Shultz had a lot of charisma, and he inspired people.

And he cared about his people, not just those who worked directly for him, but he was one of the few Secretaries of State — in fact, probably, in my lifetime, the only Secretary of State that I can remember — who cared deeply about the institution, about the Foreign Service, about the Civil Service in the institution, about the Foreign Service Institute. I mean his sense of leadership of the institution was broad, very broad.

He had an unusual leadership style that defied the classic management spread of “supervise no more than five entities.” He had 30 people reporting directly to him. I was one of them, as an assistant secretary. I had a minimum of five meetings with him a week. Four of them were in groups – a group of assistant secretaries, or a group of people concerned with national security affairs, different configurations – but I also had one private meeting with him every week, which was scheduled to last 15 minutes and could be expanded if necessary. And that doesn’t include the many emergency meetings, when we were in the middle of a negotiation or some crisis that took place in his back office.

So this was really an amazing style, which was totally changed by his successor, by Jim Baker, who had the classic management indicated pyramid of basically five. He created an additional undersecretary, and he had five undersecretaries reporting to him. He didn’t want to have Assistant Secretaries reporting directly to him. So it was a very different management style…

“They refer to Shultz as the last great manager”

Phyllis Oakley, Deputy Spokesperson at State Department 1986-89

OAKLEY: I will never forget one of my first meetings with [Shultz]. He asked me how I was doing. I told him that I hadn’t given the store away yet. He looked at me with his Buddha-like expression and said, “It will only happen once!” I think he was joking. But I must say that I was not at ease with him at the beginning – I held him in such high esteem that I was very nervous, unusual for me, despite the fact that he had invited me to chat with him on occasion.

In retrospect, I feel bad about that because he was obviously reaching out to me and I didn’t fully respond as well as I might have. I was too much in awe. In later years, of course, the relationship has become easier and much more informal, particularly at Princeton reunions where we joke and laugh together.

I will probably be best known for one particular comment I made in a briefing. This was about the alleged tattoo of a tiger the Secretary was supposed to have on his rear end – a souvenir of his undergraduate days at Princeton. We were laughing in the press office about what we might say if someone raised the question. People were giving all sorts of replies; one particularly amused me.

So when asked the question about confirming the tattoo, I said, “I am not in a position to comment!” That became my 15 minutes of fame – I am still introduced by someone who will use the quote…

Shultz was a good manager and he reached out to lots of people. There is a story that when he first came to the Department, he came alone, saying he was not bringing anyone to replace the existing staff. He told them that he would rely and count on them. It is very much what Colin Powell said when he became secretary.

Shultz held systematic and focused meetings which would include people usually not seen on the seventh floor; he would meet regularly with all officers of the Department. A story is told about the time, following a particularly tough period of negotiations with the Israelis, he walked down to the Office of Arab-Israeli Affairs just to thank the whole staff for their efforts to support him….

Traditionally when budget fights got tense, there were two or three congressmen and senators who at the last moment would come to the Department’s rescue and convince their colleagues to appropriate at least what the administration had requested. That support was not evident in later years; things changed a great deal after Shultz. But when people talk about management of the Department, particularly in the recent awful years, they refer to Shultz as the last great manager.

“Shultz was an intellectual, and he tried to develop intellectual arguments”

Richard Solomon, Policy Planning Staff in State Department from 1986-1989

SOLOMON: Shultz was very supportive of the regional bureaus — Roz Ridgway’s European Bureau was one of his favorites, and also Gaston Sigur and his Asian Bureau. All these folks had Shultz’ support, but I did as well. I would sit in on all the morning staff meetings, including the small morning meetings he held with the Assistant Secretaries back in a small inner office. I knew what was going on. I was always there and the other Assistant Secretaries knew that I had the Secretary’s ear, and in that sense I was able to stay in the game.

Much of my role — or I would say the more innovative element of it — evolved around Shultz’ growing dialogue with Foreign Minister Shevardnadze [of the Soviet Union under Gorbachev] and the other Soviet leaders.

Shultz had the planning staff pull together materials on what he called “global trends.” That is, Shultz, from his work with Bechtel in the private sector, was acutely aware of the globalizing trends in the world economy. He was very much interested in the writings and the work of Walt Wriston, CEO of Citicorp.

Shultz was an intellectual, and he tried to develop intellectual arguments to convince the Soviets that the way they were managing their affairs was putting them in a position where they could not compete with the major trends in world affairs. One trend was the dramatic shift toward political democratization, which by the mid-1980s was becoming very evident on a global scale.

For Shultz, it was particularly focused around the collapse of the Marcos regime in the Philippines, and the rise to power in 1986 of Corazon Aquino. This trend had begun in Spain and Portugal back in the mid-’70s, and it subsequently affected Chile and other Latin American countries, as well as the Philippines.

The combination of the globalizing world economy and democratization as a political trend of global scope were two developments that intrigued Shultz and gave him enormous confidence in the future of the United States. These trends provided the intellectual focus for the materials that we on the Planning staff put together, and that Shultz then used in his discussions with Shevardnadze and Gorbachev.

While we’ll never know exactly what effect those materials had on the thinking of the Soviet leadership, I assume it did help to reshape their view of the world as they tried to cope with a system that was failing. Gorbachev was trying to save the system, ultimately failing in that role.

“Shultz had a behavioral quirk”

Charles Anthony Gillespie, Ambassador to Colombia 1985-1988

GILLESPIE: In any event, I had this problem with Foreign Minister [Julio] Londono [Paredes]. He was a very proud man and, I think, also had a tremendous inferiority complex. I don’t think that he ever expected to be Foreign Minister… He was a totally unpleasant man, but not totally without a sense of humor.

I remember an incident in 1986. This was the first session of the United Nations General Assembly in which the Barco administration was involved. Foreign Minister Londono was up in New York at the UN. We scheduled a meeting between him and Secretary of State George Shultz…

Before this meeting with Foreign Minister Londono (seen left), we were doing a pre-brief at the Secretary’s apartment in the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York, where we were going to meet with Londono.

Shultz said, “What’s this guy like, Tony?” I told him that Londono was “crusty and hard. He thinks that he knows how to speak English, but his English really isn’t very good.”

However, we had Stephanie Van Riegersburg, who was the best interpreter in the Department. There was nobody better on Romance languages than Stephanie. Stephanie and I had known each other for a long time. So she was in the room with Secretary Shultz.

We said, “We’re going to have a meeting with Foreign Minister Londono.”

So she said, “Okay, we’ll take care of that. It won’t be a problem.”

We went into the meeting with Londono, who refused to say a word in Spanish. He was going to convince Secretary George Shultz that he, Londono, knew how to speak English.

Shultz had a behavioral quirk which, I think, others have probably mentioned. At a certain point you could see his shoulders hunch forward, his neck went down, and his eyes came to half-mast. He looked at whoever it was who was the point of irritation.

First he looked at Londono and then he looked at me. Then he looked at Stephanie Van Riegersburg. Then he looked back at Londono and kept staring at him while this poor man tried to express himself in English. At that point he had no control of English at all. It really was unintelligible.

I tried everything that I could, and Stephanie tried everything that she could to get Londono to switch to Spanish. We’d throw in a phrase in Spanish, saying, “Would you explain that?” He would just glare at me and then go right on, as unintelligibly as ever.

There were syllables coming out of his mouth that were not connected. It was just awful. Finally, the meeting was over. Secretary Shultz shook hands with Foreign Minister Londono.

Then, after Londono had left his office, Shultz beckoned to me with his finger and said, very slowly, “I never want to see that man again, Tony. Keep him out of my thinning hair.”