Patricia “Patt” M. Derian was one of the key proponents of integrating human rights in U.S. foreign policy at a time when such a concept was regarded with skepticism, if not outright hostility, by most State Department principals who were more accustomed to the Realpolitik of recently departed Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. Born in New York City on August 12, 1929, Derian dedicated her life to demanding justice for all people.

In the 1960s, she created an organization in Mississippi to support public school integration and then fought to get an integrated state delegation to represent Mississippi at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. She then served as President of the Southern Regional Council and was a member of the Executive Committee of the American Civil Liberties Union.

After Jimmy Carter won the 1976 election, he nominated Derian to be Coordinator for Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs—a post later elevated to Assistant Secretary of State for Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs (HA, which later became the Bureau for Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, DRL). In 1979, Derian headed an Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to investigate reports of widespread human rights abuses in Argentina. She continued this work in dozens of other countries around the world, establishing herself as an advocate for humanity and a crusader for justice.

Patt Derian describes her early life, where she moved from Virginia to California, and then to Mississippi, which forced her to confront the appalling reality of racism and poverty, as well as how she came to be the leading advocate of human rights at the State Department. Patt Derian passed away on May 20, 2016. She was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy beginning March 1996.

Go to Moments in U.S. Diplomatic History

“The strongest teaching of racism comes in those subtleties that children cannot intuit at the moment”

DERIAN: I was born in 1929, August 12. I was not told until I was about 14 that I was not fully Virginian. I was born in New York City, a real scandal. What happened was my mother obviously knew she was pregnant and I’m supposed to be born in early October, somewhere in that time. So they went to New York for the previews. They used to preview the new season’s plays in August.

During an interval my mother went into labor, which was a great shock and then got to the hospital and had identical twin daughters, which was an absolutely astonishing shock. Unfortunately, the other baby died of a diarrhea epidemic….

The only thing of real interest, how you happen to wind up living the life you do as an adult, is that I was this Catholic child in this pretty much Baptist town. There was one other teenager, a boy my same age and we were the only two kids in our little parish. I think that little parish was the only one, unless there was a black church, which we certainly didn’t know anything about.

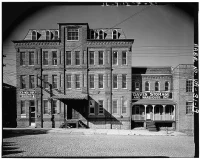

I started high school in Danville (pictured). One day when I went into Latin class a young woman, whose name I think was Mable Tanner, was the teacher and I had already had almost seven years of Latin by then, said, “Are there any Catholics in the room?”

So we raised our hands and she said, “You might as well leave, I don’t pass Catholics.”

So I, joyfully, got up and left. That class was just before lunch. A great chunk of family assembled at lunchtime for the adults’ main meal and so I went home and took my place at the table and didn’t say anything.

Finally, someone said, “Aren’t you in school?”

I said, “I’m not going back anymore.” After a while I told them what had happened, whereas they rose in a body and in four automobiles convoyed themselves down to the high school where we had a wonderful principal named Mr. Christopher.

So they finally all came back and said I could go back to Latin class. I said, “No, no, I’m not going back to Latin class” and had a little confrontation, briefly. So it was decided that I would go back but I wouldn’t take Latin, which was just wonderful joy.

Then Miss Tanner, as it turned out, was forced to come and apologize to me, which was extremely humiliating for both of us. Oh, I hated that and never wanted to see her again.….

It was just one of those things that occur to you, that every time there was someone black, a black man, maybe, obviously someone they didn’t know since everybody knew everybody else’s people who worked around there. As soon as that person would go, then we could go back on the porch [after being called inside while they passed]. That’s all there was, nothing said.

I think that’s the strongest teaching of racism comes in those subtleties that children cannot intuit at the moment…. Nobody ever told us that we shouldn’t talk to black people or that we should be rude but it was absolutely rigid.

I was an only child until I was 12 and I really think that only children grow up in an entirely different way. Particularly because I had very glamorous, party-going, party-giving parents who were almost totally absorbed in their own lives.

“I leaned against the door frame and I said, ‘I’m 13, I smoke and I’m not going to curtsy anymore!’”

I was more of an ornament because none of their friends had children. When my sister Michael was born, they were just beginning to have children. She has a lot of contemporaries among my mother’s and father’s old friends but I have none. So everyone kind of doted on me and I was alone a lot and very self-sufficient….

I spent a huge part of my childhood in Glover Park neighborhood, all by myself, climbing trees, building huts. So a big chunk of myself requires being outside a lot. In a way, I raised myself. What was transmitted to me, my father’s lifetime message to me was “You live your life so that you can look any man in the eye and tell him to go to hell!” I got a profound message from that.

Those aren’t the fighting words I grew up with kind of thing, that isn’t the effect they had on me, but it did make me weigh choices that I made, would I be proud of myself for doing this, is this a good thing to do?…

We were at one of these lunches at Del’s house and the room where you ate lunch at that house had its bathrooms upstairs. I was up there smoking and blowing smoke out the window and they kept calling me for lunch and I kept saying, “Oh, I’ll be there in a minute!” waving a towel and all of that. So I went down and I stood in the door, I must have been still 13. I leaned against the door frame and I said, “I’m 13, I smoke and I’m not going to curtsy anymore!”

There’s this long silence and I can remember that feeling of dread that I’d just cut a lot of ties. And they all burst into laughter, being people of a wild turn and they were very pleased because I pack cigarettes and they couldn’t. That was their story….

I lived [in Orinda] a while and then my father was transferred to San Pedro, to Fort MacArthur….When I moved down there I had not finished high school yet. They said that I would have to go another year before I could graduate in California.

So I came home and I said, “I’m not going. If you want me to go to college, just tell me how I should do that and I’ll do it, but I’m not going to high school anymore.”…

When the family finally got back together again, we had a serious discussion about my education. They said I could go anywhere I wanted to except to an all boys’ school and that the only thing I couldn’t do was go to nursing school. So the next morning I called the University Of Virginia School of Nursing and said, “I may not be qualified by your standards but I would like to come to nursing school there.”…

Our graduation was in September [1952] and I got married in March before I graduated, but I stayed on. My husband [Dr. Derian] was a resident in orthopedics. He was not a Southerner, and he was not from an old, old American family.

Everything about him was different. I always said I wouldn’t marry a Southern boy, their mothers had ruined them. Turned out, having married one the second time, they improve with age….

From there we went to Wilmington, Delaware, where I had my first child…. Then we went back to Charlottesville, where I had another child. Then we moved to Marion, Ohio…. And now I have another baby….

“You just have to decide how much you’re going to tolerate. It turned out my tolerance was very low.”

The medical school was in Jackson. The University of Mississippi is in Oxford [where Derian was offered a teaching position], which is a small town on the other side of the state. So that’s how I got to Mississippi.

We were there and life changed dramatically because here I was with three children and they were going to have to go to school. When we moved there in 1959, even though Brooke was only a year old and the little boys weren’t even in grammar school, yet the Citizen’s Council was pressing hard to shut down the public schools….

It had just reached the point, these men had just come back from the war and everything they’d been told about what they’d been fighting for was definitely a lie. People getting lynched. It was an astonishing place to be.

Anyway, my friend Winifred Green and I, she didn’t have any children but she’d been brought up the same way I had. We started talking about what we would do. We felt an obligation to do something….

So we formed an organization called Mississippians for Public Education. The aim of it was to keep the public schools open as well as integrated. In the early Sixties, yes.

You just have to decide how much you’re going to tolerate. It turned out my tolerance was very low, because it seemed to me, here I am facing my children, what will I say to them when they’re adults? And what will I think of myself? I was acting in a large and interesting number of things in a very hard time….

But the time came when I realized that if we were going to advance the place that we lived, we would have to step forward.

Part of my involvement was in response to when Fannie Lou Hamer and the Freedom Democrats [organized by African Americans and whites from Mississippi to challenge the legitimacy of the regular Mississippi Democratic Party, which allowed participation only by whites, when African Americans made up 40% of the state population] went to Atlantic City and were turned away at the 1964 Democratic Party convention.

That caused the Democratic Party to institute a number of reforms and when the next go-around came, which was 1968, we went through the motions of trying to implement those reforms in the Democratic Party in Mississippi. And they just didn’t do it.

So we formed a party that was called the Democratic Party of the State of Mississippi because we would follow the national party’s regulations. We had precinct, county, regional, state, went through the whole procedure and elected a delegation to the Chicago convention, half black, half white, half male, half female.

Charles Evers [Medgar Evers’ brother] was the National Committeeman. I was the National Committeewoman. Hodding Carter, [now] my husband, not then, and Aaron Henry were the cochairmen and we went to Chicago and challenged the regulars. It was the first time a traditional delegation had been denied and we were seated.

“There is really no one more impressive on the one-to-one basis than Jimmy Carter”

So, I was already working on a regional level with the Southern Regional Council, I may have been president of it then, I can’t remember. Anyway, Bob Strauss became Chairman of the Democratic Party. I talked to him in Washington one time and said, “You know, George Wallace is really not a Democrat. He’s a racist and we really shouldn’t have him in our party. We should really drum him out.”

And he said, “Okay, but I can’t do it til the midterm elections.”

So the midterm elections came and went and I waited a couple of weeks. I said, “Okay, are you ready to move?”

He said, “Oh, darling, I can’t do that! He’s the most popular Democrat in the South.”

I said, “No, he isn’t.”

He said, “You won’t be able to beat him.”

I said, “Yes, we can.”

So then I was looking for somebody to support who could beat Wallace in Mississippi. Hamilton Jordan and Frank Moore, two people who were working for Jimmy Carter, came to see me. I had only met Carter at the midterm conference, as a matter of fact. I didn’t know anything about him.

I said, “Well, if he isn’t a racist and a sexist or a crook, I’ll support him in Mississippi.” I said, “But I can’t do it til I meet him. I’ve got to determine.”

They said, “Oh, no, he’s not any of those things.”

I said, “Well, I have to determine that myself.”…

Anyway, I went to Atlanta. Had an appointment to meet him at the VIP lounge in the Atlanta airport at seven o’clock the next morning. We stayed up most of the night meeting. So when I woke up at quarter til seven I called the airport.

There is really no one more impressive on the one-to-one basis than Jimmy Carter. So I said, “Okay, I’ll do it in Mississippi.” I wrote all the rules and went out and tried to get everybody to participate, old regulars and all the white groups and the hate groups. It was really very interesting. And we did, we left Wallace in the dust….

Four women and something like 52 men. That’s how I started operating at the national level. I really had no foreign policy experience at all, except we’d traveled. It didn’t really come up except in the second meeting of the Democratic Policy Council.

“Someone from the State Department called me and said they had two jobs: protocol and something called human rights”

So after Mississippi, Carter asked me if I would become part of his campaign staff and be a deputy director and I said that I would. During that 1976 campaign my portfolio there was liberals, intellectuals, editorial boards, university types. Sort of a fireman.

Then when it was over and Carter won the presidency, I went back to Mississippi and had only been home a short time when I was asked to come up and be part of the new administration’s transition team. So I did.

I had a funny job there. I had organizations and systems of HEW [Department of Health, Education and Welfare]….I interviewed a number of former HEW secretaries.

When I went to talk to the real systems fellow at the place, one of those folks who had really been in that department from the beginning, was serious about it and able, and he said, “Look, here’s the way it works. We’ve had some phenomenal number of secretaries and nobody ever stayed more than 18 months I think.” He said, “By the time a directive reaches the field, where it first causes some kind of activity, there is not just a new one but there’s the second new one.”

So I ran into Jimmy Carter somewhere and he said, “What do you want to do in my administration?”

I said, “I’m really not looking for a job but there’s one thing I don’t want to do. I do not want to be associated with HEW in any possible way.”

So then someone from the State Department called me and asked me if I would come over. So I went, not knowing why. I assumed that they wanted to ask me about something. So they said that they’d like me to come and work there and they had two jobs: they had the protocol job and something called human rights.

I said, “Well, if I did it, I can’t tap dance. So, human rights sounds more like something I’d be more interested in.” I had worked on that. Also, I had been on the Executive Committee of the ACLU [American Civil Liberties Union] for a long time….

I didn’t like the idea of being somebody who worked in the campaign and then got a job; there was something about it that didn’t seem right. But I talked to someone I knew who worked there and said that this was a job that really had never been done. That’s the kind of thing I’m usually interested in.

You can’t take a job like that without a very clear idea of what you’re going for. I didn’t just wander in off the street and sit down. I had a clear idea. I spent my entire adult life working on civil rights and civil liberties. I worked all day every day….

You really have to refine your thinking. You have to be very clear about the basis on which you have made your decision, starting with the law and the stated policy of your Administration….

I don’t see how anybody can walk in off the street and not do a good job if they use what’s at the State Department. Even people who are opposed to what you’re doing are often extremely helpful, sometimes inadvertently. By and large, most of the time, it’s not so much personal with these people; they don’t want anything to screw up. A lot of them don’t want the Congress looking down their throat.

Q: What was seen as background for the human rights job?

DERIAN: When I went there, you see the Congress created that job over Kissinger’s objection. [The position of Coordinator had been established in 1975 and placed in the Office of the Deputy Secretary, Roger Ingersoll.] The way the legislation was written supplied a loophole, which said there would be a Coordinator of Human Rights at the level of Assistant Secretary….

The first day I was there, sitting at a desk, someone walked in with a stack of paper about 14 inches high and said, “The Secretary wants you to read this.” So I started reading and I thought, “You know, I don’t really have a big interest in this!”

So I read the whole Law of the Sea plan, which is enormously big, and marked it all up, made my comments in the thing. When I got through, I walked into [pictured, Deputy Secretary of State Warren] Christopher’s office and I said, “I don’t think this belongs to me. I think it belongs to you….”

After a while, after I’d got the hang of things, I was doing intensive studying. In fact, in the first month sometime the Amnesty International yearbook came out and so I was sitting up in bed reading about awful torture with electrodes on the gums.

About 3:30 or four in the morning I cut out the light and I went to sleep. I woke up having this terrible nightmare and I ran my tongue over my teeth and they felt like they were all broken and fractured. I knew that it was a dream but I couldn’t shake the feeling. I put on the light and had to go in the bathroom and look in the mirror to see. So I decided I was going to have to read that stuff in the morning. It was really total immersion in all the horrors of the world.

“I don’t want to come here if you want a magnolia to make it look good. I’m not going to come here if I’m going to lose these bureaucratic fights every time.”

Q: While you were settling into your job, had President Carter or White House staffers like Hamilton Jordan, or anyone talked to you about what they wanted you to do or was it sort of, here’s a job, go ahead and do it?

DERIAN: No, when I called Hamilton to tell him I was going to take this job he said, “We don’t want you to take this job. We have something much better we want you to do.”

And I said, “Well, I’m sorry, I’ve given my word and this is very interesting to me.” Before I took the job, I had a long talk with Christopher, the Deputy Secretary of State, and it was an odd talk.

He asked me about the civil rights work and essentially the methods of it. I was in a peculiar position because I was a member of the community and not somebody from another place. There weren’t a lot of white people doing it then. So civil rights work was not a wildly popular job for a long time.

But in any case, he explained certain steps in the outline of the issues that were involved in the human rights aspects of it. I said, “You know, I don’t want to come here if you want a magnolia to make it look good, you’ve got a sweet person doing the human rights job, I think you’ve got the wrong person and you need to know it. I’m not going to come here if I’m going to lose these bureaucratic fights every time.”

He said, “Well, do you have to win them all?”

And I said, “No, of course not but I have to win most of them.” So that’s essentially the time when I decided to take the job….

I was sworn in at the White House, which I was a little bit sorry about, in the Rose Garden, with [DC delegate] Eleanor Holmes Norton and somebody else and the President presiding.

At first that worried me a lot because seemed to me that was a terrific boost in a way I was not ready for. But his people came to me and said, “He wants to emphasize the fact that he’s appointing women to high positions.”

But, anyhow, here’s what I decided after I’d gotten there and sort of gotten the drift of what it was going to be like. Which was adversarial and interesting and hard and important.

I decided that if human rights was the policy of the United States and not just this president, and it was, because there was a body of legislation, then I had to do my best to insert it all over the Department.

To get it in the machinery in every possible way so that when I left, I didn’t want it to be Patt Derian’s policy. I didn’t want it to be, you know, a lot of time people have a great idea and they do a good job and then they leave and that’s the end of it.

It seemed to me that this had nothing to do with me personally. It had to do with the duty to the country and to upholding the law. So that meant that we had to get a lot of people around who had human rights as part of their portfolio. So had to work on personnel who at least while they might report through somebody else would also be reporting to us. That was one of the main things, to just get it in there and institutionalize it.

Funny, along about halfway through it, I guess, I ran into the President somewhere and I said, “You know, I really need to talk to you.”

And he said, “Well just come on over.”

I said, “No, no, I’ve got to put a request through. I don’t ever want it to be back door.” He would always say, “Just call me up if you need anything” and I never would because I wanted the bureaucracy to always be enfolded in the thing.

About two years into it, I had seen him and I said, “I’m going to do it.” And I sent a request for an appointment through and had a little trouble from the State Department Secretariat but it got through and then the meeting came. [Vice President Walter] Mondale was there. The Secretary of State was there. [National Security Advisor Zbigniew] Brzezinski was there….

So we were talking along and I said, “One of the things that concerns me is that when I send something over for your night reading, I don’t think you have good information on the human rights issues. One of the things that concerns me is that when I send some things over for your overnight reading, it doesn’t always get to you. In fact, rarely does it get to you.”

And he said, “Well, you send it to me directly.”

I said, “What do I do, put it in a brown paper wrapper?”

And he said, “Sure!”

I said, “No, I’m not going to do that. I want to send it through this whole system. I want the system to work.” So things did get better, for a while after that….

One of the other things I decided when I went there was I could never leak to the press. I called our group together and I said, “I don’t know what your custom is. All I know is, when I read the paper I see a lot of leaks out of a lot of bureaus. Here’s what I want to tell you. The only thing we’ve got here is integrity and we’re going to be straight shooters, we are going to play by the rules. We’re not going to knife anybody in the back. We’re just going to go straight ahead. When we take a position we’re going to stick with it til we’re proven wrong or another decision is made.”

And I really believe that. If you cannot go along with a policy then you ought to get another job….

It was clear one of the [Bureau of European Affairs (EUR)] officers wrote on the margins of the memo [regarding a naturalized American man who had been a Jewish refugee from Germany, who claimed he had been treated unfairly] saying, “Who does this babe think she is? What does she know about this?” Just a really nasty thing. I thought, “Oh, I need one of these!”

So I called up and I said, “I’d like you to come to my office.”

And he said, “I can’t come.”

I said, “Well I can come down there and talk to you or you can come here RIGHT NOW!”

He said, “I’m coming.”…

I said, “Don’t sit down.” I stood up to him and said, “What is this?” And he just turned purple. I said, “Who do you think you are? You wanted to know who I think I am? I think that I’m running this office and I asked you a question and I need for you to answer it. I need for you to go back to your desk and write it down and clear it and if there’s anything else you can think of you might do, you better do that, too.”

So he said, “What are you talking about?”

I said, “You can’t figure it out, that’s your problem.”

And so he called up and said, “It’s going to take me a couple of days.” I said, “Gene, you already used up your couple of days. It’s now or never.” So he rushed around, got everything and then called up and said, “Is that everything you want?”

I said, “It’s everything I need but you need something more.”

He said, “Well why won’t you tell me? I don’t like riddles and jokes.” He’s sort of half afraid and half aggressive.

I said, “I think you’ll think of it. You just put your mind to it.”

So in about two days I came back from lunch one day. I had an envelope with an apology. I know it wasn’t heartfelt but at least his mother taught him the right stuff to do. But that was helpful because the note was publicly known in EUR. If you write something nasty like that and everybody in your office sees it and of course I see all the people whose initials are scratched through.

So after we’d had enough of those little markers around, I called a meeting in the Deputy’s conference room, which was not so grand and fancy as it is now. In any case, I told them that I’d been there whatever length of time it was, and that I wanted them to understand what I thought I was going to do and how I might interact with them and what they could expect from me.

You could already see everybody’s embarrassed. Everybody’s sitting kind of like this [crossed arms] because they know. It was really a sweet setup.

So I gave them a brief outline of what the laws were that I was going to be trying to do my part on and that I intended to go to countries and visit and talk with the leaders….

And I said, “I want to tell you why I’m doing this. I’m doing this because I’ve spent my whole life working on these issues. We teach our children we’re certain kind of people. So, we need to give expression to our democracy.”